Felicia Menzel

Brasov

Romania

Interviewer: Andreea Laptes

Date of the interview: November 2003

Mrs. Menzel is a small 83-year-old woman with short, gray-whitehair, who lives alone in a three-room apartment in an old building which at different times housed a secret location of the Securitate 1 and a bank. She suffers from diabetes and high blood pressure, and doesn’t go out much. She spends most of her time alone, reading or watching TV. She is happy whenever she has visitors, and she becomes so talkative, that it's hard to slip a question here and there into the conversation. Her house is modestly furnished, she still has pieces that belonged to her parents-in-law. She was very attached to her family, and she loves to tell family stories.

My family background

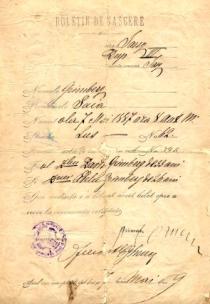

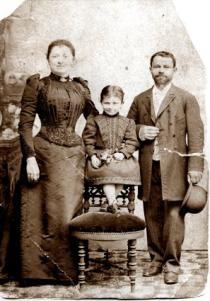

My paternal grandfather, David Grunberg, was born in Iasi some time in the 1850s; I never knew him, he died in Piatra Neamt in the 1890s, before I was born. He worked as an engraver, and died when my father was very young, so I don’t know much about him. He was married to Adela Grunberg, my paternal grandmother. We called her Booba Adela [booba means grandmother in Yiddish], but I didn’t get to know her very well either: she couldn’t stand my mother, Haia Sura Grunberg, she resented her for marrying her son. She believed that her son, my father, Saia Grunberg, could have married a rich woman. That being said, my mother had a trousseau when she got married, and her father had a shop, so we were not poor. So I never got to see her house, but I know she lived with a brother of hers, old Mendel we used to call him; however, we were not on visiting terms and my mother avoided her.

My father, Saia Grunberg, had one elder brother, Iosif Grunberg, who lived with his wife Ani in the USA, in Philadelphia. He was a photographer and she was a dressmaker, I think. They have two children, Sophie and Evelyn. Booba Adela went to the USA to live with them in the late 1920s, when I was eight or nine years old. We called uncle Iosif ‘Uncle Joe,’ and he wrote to us from time to time, as did his wife. I think my grandmother died there, in Philadelphia, some time in the 1930s.

I have heard family stories about my great-grandfather, my maternal grandfather’s father, Idel Schatz. He lived in Iasi as well, and died when he was 110 years old. He studied at a yeshivah [educational institution dedicated to the study of Judaism's traditional central texts], and he was a scholar; he was offered to become a rabbi, but he refused, he said he didn’t want to become a ‘schnorrer,’ as he said in Yiddish, a beggar. So he opened a private school for boys, where he taught them Gemara [rabbinical commentaries and analysis]. He also taught prayers, since boys were required to recite Kaddish at family funerals. He was also a chazzan at a synagogue, because he had a beautiful voice.

My other great-grandfather, my maternal grandmother’s father, was named Fainaru and he was a shop owner in Iasi. From what my grandmother used to tell me, he was a very religious man, who wore payes and a beard. I remember she mentioned to me that he was sometimes harassed by hooligans in the street, who used to pull him by the beard. He owned a shop with cereals and other grain products. He died before I was born, but I don’t know exactely when, and I am sure he was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Iasi.

My maternal grandfather, Pinhas, or Pincu, as the Romanians used to call him, Schatz, was born in Iasi in 1852, and he was a grain shop owner; he kept two modest stands in a market place that had recently opened back then. He sold all sorts of cereals like flour or corn flour, and macaroni and sugar, products which didn’t come in contact with meat. He spoke Yiddish, but Romanian as well. I know my maternal grandparents had a house of their own, but I never knew that house; I only really knew them once they lived in the same house as us. I know from my mother that in my grandparents’ former house there hadn’t been electricity; she had ruined her eyesight reading during the night or learning with an oil lamp. That old house was in Sfantu-Lazar neighborhood, which was a Jewish, or half-Jewish neighborhood, mostly intellectual Jews lived there.

My grandfather was a religious man, quite religious, because his father had been a scholar: he went to the synagogue on the Sabbath and High Holidays, wore tefillin and observed kashrut. He didn’t have payes [side-curls] or a beard and he never shaved with a blade [it is forbidden for men to use a blade to shave according to traditional orthodox Judaism]. Someone, a barber I think, came to his home and trimmed his beard with a machine. He went to the mikveh every morning and when he came home from work in the evening, he washed, changed his clothes, took a religious book he had from his father, and went into a corner to read, that was his relaxation. Also, every evening he said his prayers singing, he had a beautiful voice like his father. He wore tefillin when he prayed at home, but not the tallit, he wore it only in the synagogue.

He was married to my grandmother Seindla Schatz, nee Fainaru, who was born in Iasi in 1866. She spoke Yiddish as well, and she too was religious: she lit candles every Friday evening and she cooked kosher food. She observed the Sabbath, but she only went to the synagogue on the High Holidays. She didn’t wear a wig or a kerchief. I don’t think she had any schooling, she was a housewife, but she helped my grandfather at the counters in the market: she sold merchandise, at the retail counter, and my grandfather sold at the wholesale counter. Their business was rather good, the market was near the law court in Iasi, and a lot of people did their shopping there.

My grandfather wasn’t politically involved, but we kept a Keren Kayemet 2 box in our house. My grandmother was strict, and a dignified person, she never went in anybody’s courtyard, and she didn’t talk much with our Christian tenants, who rented a room from us between the two World Wars.

She had a few quarrels with my grandfather, I remember, because he used to take presents, products and the like, to every rabbi who was in Iasi, to show his respect, not for anything else, he wasn’t looking for help. But their financial situation wasn’t so good; they were working hard, so sometimes my grandmother didn’t approve of all these presents.

My grandfather used to be quite a merry person in his youth, I was told, but when I knew him he had heart problems already: he suffered from angina pectoris, which he got when he ran after a tram and fell.

My grandfather had siblings who left for the USA, but I don’t know their names. My grandmother also had three sisters who all left for the USA: Roza Katzman, Freda and Lea. I don’t know why my grandparents didn’t leave for the USA as well; but life wasn’t easy back then, and their siblings couldn’t have helped them very much. Moreover, my grandfather was very religious, and he was the only one who could recite Kaddish after his parents died.

My mother, Haia Sura, was their only child. I heard two versions about why my mother was the only child: my grandmother used to say that my grandfather hurt one of his testicles as a child in a fall, which is a true story, but it turned out that it wasn’t the cause of the problem! But when my mother was a young woman, she took her mother to a doctor at an age when she was still young and could have borne children, and the doctor told her she had a problem caused by my mother’s birth, which prevented her from carrying another child.

My mother was born in 1888 in Iasi, and her mother tongue was Yiddish. She studied at a boarding school for young ladies in Iasi, which belonged to two old German spinsters, so she knew German very well. I remember my mother used to tell me that her mother used to tie her beautiful hair in a pigtail with a taffeta ribbon. One of the Knoch spinsters, who was more ill-tempered, always got mad at my mother, because when she moved, the taffeta would creak, and she used to cry out, ‘Du Fratz!’ [‘You little brat,’ a very Austrian German term]. Mother worked as well, but before she married: she taught German and manual training classes at the Jewish school in Iasi; my mother was known in Jewish circles because of her father and grandfather.

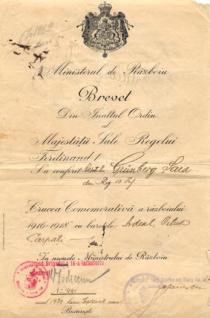

My father, Saia Grunberg, was born in Iasi in 1887. He spoke Romanian, and he studied at a business high school in Iasi. He worked as an accountant and as a proxy for another Jew named Horovitz. I never knew my father, he died in 1921, when I wasn’t even a year old. Everything I know about him is from stories my mother told me.

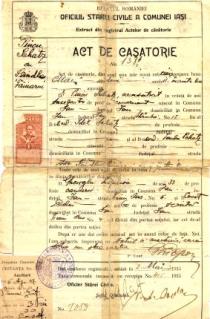

This is how my father met my mother, Haia Sura Grunberg [nee Schatz]: at a Social Democrats club, they were both Social Democrats. They fell in love and got married in 1914. They had a religious wedding, my grandfather wouldn’t have had it any other way: but the wedding didn't take place in the synagogue, they had the chuppah at home. My father refused to wear a gold wedding ring, he thought it wasn’t proper for a social democrat, so only my mother had a wedding ring. [Editor’s note: Jewish women receive a wedding ring at their wedding, men don’t need to wear one.] My mother’s parents weren’t against my father because he was a social democrat; their daughter was one as well. He wasn’t very religious anyway. My mother used to say, as a superstition, that if he had worn a wedding ring, maybe he wouldn’t have died so young.

My mother would never have married a Christian, not so much for her sake, but she adored her parents, and her father was especially religious. My father was quite passionate about Social Democracy, he even wrote articles in newspapers, like Romania Muncitoare [Workers’ Romania, a Social Democratic newspaper]; he had a quick temper, from what my mother told me about him. My parents went camping to celebrate on 1st May. It was more like a party, workers came of course, but it wasn’t much of a parade. After my father died, my mother didn’t go anymore.

One year after they got married, in 1915, my elder sister Angela was born. My father had already left for war; in 1914, he was drafted to the Romanian army. During World War I he fell prisoner to the Austro-Hungarians, in Slovakia. He was held hostage until the end of the war, in a place called [in German] Trentschin-Teplitz [Trencianske Teplice in Slovakian]. My mother didn’t know where he was for a while, she was desperate, so she kept on going to Bucharest, to the army’s general staff, and she persisted until she found out that he was alive. My father came home in 1918.

My father spoke Italian very well, and when he came back from the war, he was sent by his employer to Italy, and, with his gift for languages, he became fluent in Italian in six weeks. So those Italian partners, who were in the weaving industry, grew interested in him, and fond of him as well, so they gave him a new job, supervising their new representation in Galati. We almost moved to Galati, because of my father’s business interests there, but my grandfather wouldn’t hear of it, he didn’t want to leave his synagogue and his rabbis.

My father set up the business with the help of two of his Social Democrat friends, he had no money of his own to invest. This was his occupation between 1918 and 1921, but nothing much came out of it, because he soon died. He fell ill with flu, got a septicemia and died. He was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Iasi, named Pacurari; my maternal grandfather recited Kaddish for him.

The house we lived in was an old house in Iasi, on Anastasie Panu Street, with three rooms, a balcony, and with the toilet and the kitchen on the balcony. The rooms had no separate entry, each one led into the other, in a row, so if you wanted to go from the last room outside, you had to go through the other two rooms. Several neighboring houses shared our courtyard, but there was no garden, and my mother didn’t grow anything as the yard was paved. We had running water and electricity.

My father had bought our house, the one I lived in, but unfortunately he never got to live in it, he died before we moved in. I was born in 1920. After his death, in 1921 my grandparents came to live with us: it wasn’t proper for my mother, being a young widow and their only child, to live alone. Our financial situation wasn’t great, but I never knew what hunger was, or what it felt like not to be able to buy an orange or something like that.

Growing up

When I was little, I met a few rabbis that were in Iasi, because my grandmother wasn't happy for my mother to be so young and remain a widow with two children, she wanted her to remarry. The rabbi, one from Sighet, came home with the shadkhan, a nice old man, but my mother didn't like anyone they suggested. I remember that my sister and I were introduced as well, and I burst out laughing when I saw that the rabbi went into a corner to pray. We had to leave the room immediately, my mother only cast a glance at us but we knew it meant trouble. We laughed because we thought it was funny how he went into a corner and started praying all of a sudden, because he didn’t look like a rabbi to us, he had no payes or beard.

Even after that there were rabbis from Cluj, from Buhusi [town in Bacau county, on the bank of Bistrita river], from Stefanesti [in Botosani county] , but my mother didn’t accept anybody. So although she was still young, my mother never remarried, she didn’t fancy anyone. And it wasn't for lack of interest in her: I remember during the war, because our father was home the army requisitioned one room, and a professor from Galati, a Christian named Tohaneanu, lived there and he fell in love with my mother. But he was a very polite and well-read man, and my mother talked to him, about books of course. He never crossed the line.

We observed the Sabbath, my grandfather didn’t work, and someone from the families we always had as tenants came to light the fire. We had a servant who did the cleaning, but my mother and grandmother did the cooking. The food was kosher, we kept separate pots for milk and meat; I remember arguments about that, because sometimes the servant washed a fork that came in contact with milk in the basin for the pots that came in contact with meat. When my grandmother noticed, there would be a big scandal, and the servant had to go.

For Friday evenings my mother cooked gefilte fish, I liked to watch her cook: she removed the skin and the bones, then she minced it, tradition said you had to mince it three times in the machine; then she added eggs, pepper and flour or bread crumbs, I don’t remember exactly. We didn’t have soup all the time, but we had boiled poultry, with potatoes and a cake.

My mother wanted to have time to say the blessing rather than spend too much time cooking on Friday afternoon, so on Thursday she always cooked traditional Moldavian sponge cakes, they were delicious, and other cookies as well. I didn’t have time to help my mother much in the kitchen, I was busy with school.

Before dinner, my grandfather went into a corner and said a prayer, and everybody had to keep quite while he did that. He said blessings if he ate fruit, he recited the kiddush on Friday evening, my grandmother lit two candles. My grandmother was the one who lit the candles on Friday evenings, she used the Yiddish term ‘bentshen likht’ for the blessing she said. At the [conclusion of] the Sabbath my grandfather said Havdalah. My mother didn’t observe the Sabbath very strictly, but she tried not to light the fire, she didn’t sew, she didn’t cook.

My mother went to the synagogue only on the High Holidays, more for her father’s sake, as she didn’t want to upset him. When I was little, on the High Holidays, I went to the same synagogue as my grandparents, but my mother used to go to the big temple: the rabbi there was married to a former school friend of hers. My grandfather liked his synagogue, all his friends were there. The prayers stopped at 10am for a break, ‘osmenes’ in Yiddish, and he usually was invited to lunch or for refreshments at one of their friends, who lived close to the synagogue.

Our home was kosher over Pesach; my mother kept special tableware just for Pesach in the attic, in a trunk, and nobody was allowed to touch it except for my grandfather, who went up in the attic to get them on Pesach Eve; of course, there was a lot of cleaning beforehand. On Pesach we didn’t eat bread for eight days, only matzah; we were so desperate for bread after that!

We observed the Seder Eve, my grandfather sat in an armchair, on a cushion, and he read the mah nishtanah [Editor’s note: usually the four questions are asked by the youngest participants of the service], but I don’t remember ever having afikoman, maybe there was afikoman when my sister was younger.

On Chanukkah, my grandfather would light the candles one by one, every day; we had a silver chanukkiyah. I never received presents on Chanukkah, only Chanukkah gelt. It was just a few coins, which my grandmother usually gave us, but we didn’t mind. We didn’t dress up for Purim at home, it wasn’t such a merry house because we were lacking a father. But I remember, one of our Jewish tenants, Miss Mita, organized some festivities at the Jewish school where she taught, and she invited us as well. My mother made me a beautiful domino suit, with white and blue, and a cap, but I fell ill and I couldn’t go in the end.

Iasi had a very big Jewish community, with all sorts of functionaries, and synagogues, and the big temple, and mikves and so on. I don’t know exactly how many mikves were there, but I remember my mother told me, that when she was a young woman, before she married my father, she used to go to the mikveh with her mother, after her period. [Editor’s note: Married women go to the mikveh for ritual immersion after each period, after which they can again be with their husbands.] My mother told me that for the Orthodox Jews, a woman having her period was considered dirty, and the man didn’t touch her. [Editor's note: It is understood that a period signifies the loss of a potential life. A woman is not considered dirty, rather she is in a state of spiritual impurity during her period, after which she immerses in a mikveh to become spiritually pure again]. That’s why in the couple’s bedroom there used to be two beds, because the woman had to sleep alone when she had her period. After she gave birth to my sister, mother told me that the Jewish women came to see her and bring her sour-cherries as gifts.

I remember, close to Rosh Hashanah time, my mother used to send me with the servant to the hakham [wise man/rabbi]: she was afraid that the servant girl would just kill the chicken herself and keep the money we gave her for the hakham, these things happened sometimes; so I was sent to supervise! [This is a ritual that takes place before Yom Kippur which involves pledging a sum to charity.]

On Rosh Hashanah, after my grandfather died, my mother read the prayers; she learned that from her grandfather, because my grandmother didn’t see that well anymore. She recited them very well. My mother had a good voice, she sang to us sometimes, when she was in the mood. On Yom Kippur, my grandparents fasted, and my mother fasted too for as long as they were alive; but after that, she didn’t. I think she did it for her parents’ sake, but she herself was a bit angry with the idea of religion, because her husband died so young. We kids never fasted, however.

I never went to the market with my mother, she wasn’t allowed to exert herself, she had high blood pressure after my father died; usually, the servant went shopping for groceries, or sometimes my grandmother. Also, I remember there was a poor old Jewish woman, named Malka. She never begged, but she always carried a big bulrush basket and my grandmother used to send her to the market to bring home what we needed, and she paid her for that.

I remember one time, it was the Easter holiday, it was warm outside, April I think, and Malka came into the kitchen, with her basket. We girls were educated of course to have clean hands and clean nails, and then I noticed that Malka’s nails were black from dirt and dust; so I went to fetch my scissors, and cut her nails. I was nine years old I think, and still in elementary school. Malka was stunned, she wasn’t used to being treated this way by kids; but I was a merciful child, I liked old people, and very young children as well: I remember, whenever one of my mother’s tenants gave birth, I wouldn't move from their bedside, I was fascinated by them, they were like dolls!

We had a library in our house, but when I was little it was locked, because my mother had books on sexology, which a child shouldn’t read. But of course she gave me books to read, the ones I was allowed to. All the books were in German, and they were mostly about pedagogy, sexual education and so on. My mother never hit us, she was a fan of pedagogy. She read Rousseau. [Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778): French deistic philosopher and author of the famous ‘Discours sur l'origine et les fondements de l'inegalite parmi les hommes’, ‘Du Contrat social.’] There was a book about Lenin’s 3 life, and one sent to my father from Uncle Joe, called ‘Why I am a communist,’ but these were the only communist books.

We had religious books as well, lots of them, from my great-grandfather and my grandfather. They were all written in Hebrew, they were about the Gemara, but I don’t remember the titles. I remember my grandfather always read by candle-light when it was one of his religious books, and that I loved to stay near him. The wax melted and fell on the paper, and I liked to scrape it from the leaves of the book. My mother didn’t advise me what to read, I read the books we had in school, I didn't need any encouragement to read, I loved it.

Between the two world wars, we always let out one room, so we could have money to cover our expenses. Once, one room was rented to two Christian priests: you can’t imagine, what they did, they got drunk, came home during the night, made quite a row, and my mother had to sleep with her parents, because they had to go through her room as well, and she was alone, she was afraid that they would come over to her.

I remember, when my grandfather came home from the synagogue on Saturdays, he took me by the hand and walked with me in the street until lunch was ready; we talked about all sorts of things: how was my day, how was his, and so on.

I remember a funny incident that was the topic of one of these Saturday conversations with my grandfather. Usually, our tenants in the spare room were Jewish girls, one or two, students in Iasi. Jewish students sought out my mother, because it was known that our house is a Jewish home that respects traditions.

One of these tenants was Mita Iacobson, from Ivesti, near Galati; she was a teacher at a Jewish school in town. She came from a religious family as well and my mother was usually very friendly with her, and with all the Jewish students. She helped them sometimes with their homework, and they ate in our house, because the food was kosher and they didn’t have to go out into town to look for a Jewish restaurant. Actually, the kosher canteen for Jewish students only opened later.

I adored Mita, I was four or five years old, and she used to talk to me. One evening, when Mita was free because she didn’t have classes the next day, my mother was chatting with Mita in the living room, joking and so on. Now, Mita didn’t wear any make-up, and she wore her hair pulled up tight, in two plaits; my mother, on the other hand, did wear a bit of lipstick once in a while, and jokingly, my mother taught her how to wear lipstick and made her wear it for the evening. When I saw Miss Mita, I was a polite girl, I always called her Miss,, I said to her, ‘Oh, my goodness, Miss Mita, you look so beautiful, you look like a cocotte!’ And I must tell you, cocotte didn’t mean a coquettish woman, it meant a tramp, or a whore!

She went straight to my mother and told her, ‘Guess what Felica, that was my nickname, called me!’ My mother was stunned, she was a very decent woman and she couldn’t imagine where I had heard that word. But nobody scolded me, only on Saturday, while we were walking my grandfather told me, ‘You know, you called Miss Mita a word you are not supposed to use.’ and so on. I think he had pedagogical talent, like my mother.

The bottom line is, I had heard that word at one of my mother’s meetings, when she gathered with the Jewish ladies that were in school committees, like her. No matter how decent they were, and they were, the word slipped out during their gossiping. I must have overheard it and misunderstood its meaning. But my mother rarely had guests over, she only invited people when she had also been invited, because she was very busy with the household.

My mother mostly had Jewish friends; I know she had one Christian friend, a female doctor she got to know while she was at Vatra Dornei [spa region located in Bistritei Mountains, in Suceava county] for high blood pressure treatment; they made friends and they were on visiting terms. We sometimes visited some other relatives of my father, some cousins, the Bughici family. They were all musicians, my father also had a very good voice, and one of them, Dumitru Bughici, was a composer.

My mother went on vacation a couple of times while my grandfather was still alive. I remember she went to [the former] Czechoslovakia, where there were two famous spas: Karlsbad [famous spa in the Czech Republic], for the rich Jews, and Franzensbad, for the middle-class ones. My mother always went to Franzensbad, as she had to take care of her high blood pressure. I think she also went to Zizin [Romanian spa located at the foot of the Ciucas Mountains in Brasov county, famous for its mineral springs]. I went on vacation with my mother and my sister as well, once to Techirghiol [town in Southeastern extremity of Romania in Constanta county, situated on the shore of Lake Techirghiol, an all-season resort], and twice to Vatra Dornei.

Our neighbors were mostly Jews, because it was a Jewish neighborhood, and my mother got along well with them; she wanted to be respected, especially because she was a widow. She didn’t make friends with our neighbors though; I think her friends were a bit more intellectual. In any case, she had very little time for socializing, the house always needed repairs, she had two kids to raise, and two parents to take care of, because they were busy with the shop during the day.

I went to parades on 10th May [commemoration of the crowning of the first Romanian King, and the creation of the Romanian Kingdom, which took place on 10th May 1883]. I was in High School already, and it was compulsory to go: we stood by the side of the road and watched the military parade. I remember the 13th infantry regiment, which was from Iasi, and the students from the boys' High Schools marching.

There were rich and poor Jews in Iasi alike; the poor ones were mostly craftsmen, like tailors or shoe makers. I remember one shoemaker in particular, who came into the courtyards and called out that he fixed shoes. But he, like many other Jews, didn’t speak Romanian very well, so he called out, ‘Repar iefti!’ [in Romanian: ‘I fix chea!’] instead of ’Repar ieftin!’ [‘I fix cheap!’].

There were Jews who were better off, like Ehrlich; he worked across the street from our house. He was the director of the first weaving mill in Iasi; he had a Bohemian wife, I remember, and he owned a La Salle car, to the delight of all the boys in the street, because that wasn't something you saw every day back then. I liked to watch him come to work in the morning, he always pressed his horn!

My grandfather had a shop, which was nothing fancy, just three iron compartments with the merchandise in them. My grandmother used to sell at a counter in front, and she stood on some steps a bit above the ground, because it was very cold in autumn and winter. I remember they used to heat the shop with charcoal, and it was a bit dangerous, because the fumes could be toxic, although it never caused them any problems. My grandmother left the shop earlier than my grandfather, to come home and fix dinner.

My grandfather died in 1928, he had a heart attack while he was at work. After he died, my grandmother sold the shop. I only found out that he had died when I saw my mother and grandmother sitting shivah: they wanted to keep it from me for a while, because I was very close to my grandfather, he was like a father to me. So I didn’t go to his funeral, but I know he was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Iasi, in Pacurari, and a relative of his, I don’t know who exactly, recited the Kaddish.

When I was little, I never went to kindergarten, so I spent most of my time playing in the courtyard; I made friends quickly with the other kids, but especially with the boys; that's why my mother sent me to school when I was six, because I wanted to go out of the yard with the boys, strolling or finding other places to play, and that wasn’t proper for a little girl.

I didn’t have a nanny; my father had been strongly against it, he was a great patriot, and didn’t approve of his children learning a language other than the one of the country they lived in. So my mother took care of me, with the help of the servant. I played most of the time, and when the weather was nice, my mother took me out for walks in Copou [Iasi’s central park], to listen to the fanfare that played in a kiosk in the center of the park.

Also, my sister Angela had to take care of me, watch over me, my mother insisted on that, because she was five years older than me. I remember when I was a bit older, Angela had to take me with her all the time, and her friends were sometimes annoyed, they said to her, ‘Why do you keep bringing Feli to be on our tails all the time?’

When I was about six years old, my mother brought an old, ugly spinster to teach me Hebrew. Miss Smuckler was a Hebrew and Yiddish teacher at a Jewish school in Iasi. I was usually an obedient little girl, but I didn’t want to listen to her, I gave her a hard time; I didn’t want to answer her questions, I was stubborn. When I was little I didn’t like ugliness in any form, I liked beautiful people, and Miss Smuckler was ugly, so her lessons didn’t go that well!

My mother didn’t punish me and she didn’t insist on me continuing the Hebrew lessons, she had done that for my grandfather’s sake mostly. She also knew from her own grandfather what it felt like to be forced to learn something you didn’t like. She had been in the same situation: her father wanted her to learn Hebrew, the Talmud, as the only child, but she wasn’t especially drawn to that. And her father complained to his father, my mother’s grandfather, and he said, ‘Let her be, she will be an ‘oyfgeklert,’ that means a free spirit, a free thinker in Yiddish.

I was very fond of Angela. One time, she was taking violin lessons, and she was at her teacher's house, when a terrible storm broke out. I was terrified of storms, and I started crying and screaming that Angela was in danger if she came home alone during such a storm; I was only five, I think, but my mother or the servant, I don’t remember who, went to pick up Angela for my sake, otherwise they wouldn't have been able to make me stop crying!

I went to a normal elementary school, whose principal was a Romanian, Mrs. Botez; I remember I was quite afraid of her; she was a very imposing woman, a colonel’s wife. Once, I went out to play with the kids when my mother was out, picking up Angela from her violin lessons, and I lost track of time. When my mother and sister came back, I was still out and I hadn’t done my homework, so Angela did it for me; the teacher noticed that it wasn’t my handwriting!

After elementary school I went to an Orthodox High School, whose principal was Princess Cantacuzino. [Editor’s note: Alexandrina Cantacuzino was the president of the Society of the Orthodox Romanian women and founder of the Orthodox schools and high schools in Romania.] I went to that High School because of a friend of my mother’s, a doctor, Mrs. Dona, whose daughter taught history there, and probably recommended it to my mother.

I was a good student, and quite appreciated: I sang in the choir, and on one Christmas, I received a box of sweets with a note saying that I was delicate, disciplined and well brought-up. I didn’t celebrate Christian holidays, but I took part in the festivities, as I had to sing in the choir; also, I took classes about the Christian religion. Once on an Epiphany festivity, I was sprinkled with holy water by the metropolitan bishop himself! [Editor’s note: The Epiphany is celebrated on 6th January by the Anglican, Eastern, and Roman Catholic churches. The feast is still recognized in the Eastern Church as the anniversary of the baptism of Christ, when the holy water is blessed by a bishop or priest.]

I remember that sometimes I came home singing Christian songs, like ‘Ceresc Tata’ [Holy Father in Romanian], and my mother made fun of me, saying, ‘Are you singing Ce razi, Tata’? [a play on words, meaning ‘What are you laughing at, Father?’]. Among Jews, it was forbidden to pronounce the name of Jesus, and my mother, when she didn’t approve of the behavior of some Jews, Jews were good and bad, like any other human beings, used to say, ‘They are the kind of Jews who tortured the Christian God!’

There were many other Jewish girls there at the school, like a friend of mine, Toni Moscovici, but the Jewish girls had to pay a higher fee for education than the priests’, officers’ and teachers’ daughters, who benefited from a reduction. So the principal talked to my mother and advised her to move me to Mihail Kogalniceanu High School, which was cheaper, and in a Jewish neighborhood, which my mother did, especially because Angela was studying there as well.

I didn’t have many close friends in school, I was shy and not very talkative back then. At the Orthodox High School I got along with Chichi Patriciu, who was the daughter of the principal of the High School for boys in Iasi. However, we weren’t on visiting terms. At Mihail Kogalniceanu High School I got along better with Felicia Lobl, a Jewish girl and a former neighbor of mine.

I liked all subjects at school, but I found mathematics a bit difficult. The teachers were very good however, except Professor Otetea, who was an academic, and taught history. He was a very good teacher as well, but he had published a book, and insisted that we studied from it, word by word, which I couldn’t do; so I didn’t like him much.

I was never part of an organization, sports or cultural; we did have some gymnastics classes in High School and some dance classes as well, but that was all. My sister and I never had private language lessons, we didn’t need them; we learned very well in school, and my mother knew German, so she could help us with our German homework: she didn’t teach us though, there was no need, we learned German in school. I took piano lessons but not for long, as money was short for that; a former friend of my father’s had lent me a piano to practice on.

During my High School years, I went to concerts and operettas rather often, I once even heard Enescu play [George Enescu(1881-1955): a Romanian violinist, composer of eleven symphonic works, renowned conductor and teacher; among his students were Yehudi Menuhin and Dinu Lipatti.] I didn’t go to the theater that much, although my sister used to take me when I was smaller to plays for children, or puppet shows.

I remember the political climate before World War II, my mother talked about it. I remember one funny incident concerning Cuza [after whom the Cuzits 4 naming comes]. My mother had a cousin, Ela Finkelstein was her name: Ela was more beautiful than my mother, but my mother was well-read and polite, so they spent time together. Before the war broke out, Ela and my mother went to the university in Iasi, to attend lectures on the German language, as that was my mother’s specialty. They weren’t students, they just went there from time to time.

Herr Professor Cuza was renowned for his anti-Semitic opinions, and for the fact that he only spoke German with the Jews, despite knowing Romanian. He was also renowned for two other things: that he talked in a lisping voice, so he pronounced ‘j’ as ‘z,’ and that ‘he didn’t like Zews, but he did like Zewish little women’!

So one day, my mother and Ela were coming back from the university, and their shoe laces got loose, they had probably left the university in a hurry: so Ela bent down to tie my mother’s laces, as my mother couldn’t do it herself, because she was wearing stays, and so was Ela. When it was my mother’s turn to tie Ela’s shoelaces, out of the blue appeared Herr Professor and tied Ela’s shoelaces; and he knew very well that they were ‘Zews’!

I remember there was talk in our house about anti-Semitism; my mother thought that the greatest anti-Semites were the teachers, professors and priests, because they were teaching the students to be anti-Semites too. There was also a common prejudice, that Jews have red hair, which wasn’t always true. ^

I experienced anti-Semitism, but not in a violent way: I remember when I was in High School, I was going back to school by tram after coming home to eat lunch. It was the afternoon, and in front of the tram there was a Jewish funeral convoy, that went to Pacurari, the Jewish cemetery in Iasi. I went to the front of the tram as I was late so I wanted to be the first to get off, and I heard the driver say, ‘I hope as many of these [Jews] remain, as I have baptized!’ I was shocked, but I didn’t say anything.

My sister, Angela, right after she graduated from High School, went to study Italian in Bucharest, in my father’s memory. But she only studied for one or two years, as my mother didn’t have enough money to support her for the full four years. Once back in Iasi she took up law, but she had to drop out from university, as she had problems with her colleagues, they beat her with snow and insulted her. So after three years of studying law at university she had to drop it.

We came to Brasov in 1938, mainly because of my sister’s health. After she went on vacation with my mother to Valcele [commune and spa situated in Covasna county, well-known for its mineral waters], she came back unwell; she had developed a strange allergy to cat hair, which was hard to treat and which was discovered rather late.

During the war

By 1938 it grew harder and harder to find a job; so, because of that and because my mother didn’t have money to send Angela to spas as often as she needed, we decided to come to Brasov, which at least had good clean air. When we moved to Brasov we had to leave most of our books behind, as we couldn’t carry them, and when we came back for them in 1944, some of the neighbors we still knew told us that they had burnt them, because they were communist books!

Angela found a job as a secretary at the Electrica plant; one of the two managers was Italian and he needed someone who could speak the language. At first only my mother, Angela and I came to Brasov; it was only after Angela found the job that we brought my grandmother as well. In the meantime she stayed with a relative of ours in Iasi, one of her nieces. My grandmother died in Brasov in 1942, and she was buried in the Orthodox Jewish cemetery here; it was somebody from the community who recited the Kaddish, I don’t know who.

We were lucky that we came to Brasov, we didn’t suffer much from anti-Semitism; there were anti-Jewish laws [in Romania] 5 of course, but no pogroms, like we found out there had been in Iasi: a distant relative of ours, a cousin’s husband, Gust, and their son, Saia, were murdered.

My mother found out about it in the following way: one day somebody came to tell her that there was a train with Jews from Iasi at the railway station, and my mother hurried there. She met some acquaintances who told her what had happened. Their story was that the legionaries 6 had climbed on the roof of Braustein’s elegant footwear shop, and fired at the Romanian army, which was marching through Iasi towards the Prut river. Then they blamed the Jews, because the shots allegedly came from a Jew-owned building. So that was what caused the pogrom in Iasi. Our relatives were among those shot in the prefecture’s courtyard. The ones in the train were the ones sent to forced labor camps in Campeni.

At first we rented a furnished room. Then thanks to Angela, we could afford two rooms. I couldn’t find a real job: I had to tutor elementary school girls, with all their homework, in all subjects. My mother also started to tutor elementary school girls at home in German and there was a German elementary school in Brasov, so there were plenty of pupils who needed her help. But one Saxon woman found out, I don’t know how, and she caused a row at the school, because a Jewish woman was teaching Saxons’ children; many of the Saxons were anti-Semites, so my mother had to stop. So basically, my sister supported all of us, me, my mother and my grandmother, throughout World War II. I was unemployed until 1944.

During the war, everything was considered normal, all the anti-Jewish laws. We had the right to buy milk and bread, for example, but only after 10 o’clock in the morning, so that the Romanians could be the first to buy what they needed. It was a common prejudice that Jews speculated with everything, food included. There was a ‘Molkerei’ [German for ‘dairy shop’] in town, where my mother used to go. It was owned by a Saxon woman, and every day at ten, she would close down the shop for a few hours, so that she didn’t have to sell milk to Jews. In the end, my mother made friends with some peasants from Stupini [a village 5 km from Brasov], and they gave us milk, so that problem was solved.

We had no idea about the deportations of Jews, we were a bit stranded here, we didn’t know the Jews from the community very well; we found out only later. I remember we had a Saxon friend who told us later that even they, the Saxons, were amazed to find out about the deportations.

I met my husband, Zoltan Menzel, during the war, in 1940, in this very house I live in today, just upstairs, in a Jewish club called Ahava. I don’t know if it was a Zionist club or not: it had several rooms, in some the ladies drank tea, and in others the men played cards. They organized balls from time to time, but that's all I know about the club. Zoltan wasn’t a Zionist though, and neither was I.

My mother, on the other hand, gave money to help Jews in prisons, or for other Zionist purposes. It was called the Red Help, and she did it throughout the period between the two World Wars. [Editor’s note: The Red Help was an underground communist organization, which helped the imprisoned communists with packages, and their relatives who remained without support with money.]

During the war, Zoltan was drafted to forced labor, together with other young Jews from Brasov, and he had to go to work in construction, digging all over Brasov county. We got married when the war was over, in 1944. I don’t know if it mattered so much to me that he was a Jew, but I didn’t like anybody else. We didn’t have a religious wedding, that cost money and we were broke, both unemployed.

Zoltan was born in Budapest in 1915, but after World War I he moved with his parents to Brasov, when he was in second grade at elementary school. He went to a German High School here in Brasov, called Honterus. [Named after Johannes Honterus, where all the classes are taught in German.] He graduated in 1933, when Hitler came to power and anti-Semitism started to spread. I think he was in a special class: all of them remained united and close until they grew old and died. Every year they celebrated the anniversary of their High School graduation, either in Munich, Germany, where some of his former colleagues were living at the time, or here, in Brasov. My husband also went to the Jewish school here, he took some classes while at High School; he was Rabbi Deutsch's favorite student! His mother tongue was Hungarian.

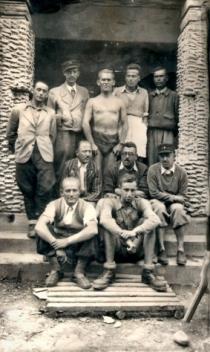

His father, Iulius, worked as a commercial manager at a wood factory, and his mother, Etelka, was a housewife. At first, his mother didn’t like me much: I was brought up to be an honest and dignified person, and she was used to all the Hungarian girls who were pursuing Zoltan, and who were buttering her up all the time. Zoltan was a handsome man, and women were crazy about him: he even had a photo album with all his former lady friends! I needed a lot of patience, I even tore up a few photos of some good-looking girls, but my patience paid off: we married, and had a very happy marriage.

My mother-in-law was a religious woman, but it was a different story with my father-in-law, who got baptized. It was such a scandal! When he came to Brasov, he made friends with the Lutheran priest, and he finally got baptized, I believe the priest persuaded him. His wife was so angry with him, she didn’t speak to him for weeks. He did it when anti-Semitism started, maybe he was afraid, but when I asked him why he did it, he said that with Jews he had to wash his hands too often! It was a joke, of course, I think he was referring to the mikves, or to the fact that Jews were very clean people, and every time they used the toilet they washed their hands. My mother-in-law felt stranded from the community with such a husband, so she didn’t go the synagogue anymore.

In my new family, we only observed some of the traditions; we observed only the High Holidays, especially Pesach. I was working, Saturdays weren’t free, so I didn’t observe the Sabbath and didn’t light candles on Friday evenings. The hours at work were long, and then there were the chores around the house when I came back home, there was no time for tradition. However, Zoltan, Zoli as was his nickname, and I paid membership fees to the Jewish community. I did participate in conferences when important scholars or well-read Jews were invited to talk during communism. I remember listening to Mr. Nicolae Cajal [member of the Romanian Academy, President of the Jewish Communities Federation of Romania].

After the war

My sister married Ioan Sangeorzan, a Romanian, in 1944. He was a technician, and during the war he studied law in Cluj, but he was drafted by force into the Romanian army. He ran away, however, and came to Brasov. His brother had rented a room in our apartment here, that's how they met. They didn't have a religious wedding.

They have a daughter, Doina, who was born in 1952; she's married to a Jew, Petrica Vecsler, a doctor. Doina and her husband left for Canada in the late 1970s, I don’t remember exactly when, and then they settled in Milwaukee, in the USA. Doina is a housewife now, although she was to become a painter, she had great talent. She has two children, David and Julie, and she still calls me sometimes; I am very fond of her, she was like a daughter to me.

Angela and Ioan also left for America in the late 1970s, they couldn’t stay away from their daughter, and they settled in Milwaukee as well. My sister doesn’t observe Jewish traditions much, she wasn’t very interested, but my niece, Doina, does, together with her husband. I know their son David Robert had his bar mitzvah.

After the war, my husband worked as an accountant. My first job after the war was as a secretary for a Swiss company. Right after the war, there was a strong campaign against everything that was German, including the language and the literature, which was plain stupid, because the German people had achievements as well.

I was hired because I knew German and French: the manager, Zender, was a German, and he had a beautiful French wife. The typist was a Saxon woman, and she wrote down all correspondence in German. But as it was common practice that correspondence was written in French, I had to translate from German into French, which was rather hard: his wife helped me as well. Zender closed down his business, he was terrified of the Russians gaining power, and after that I worked at the Electrica plant as a secretary.

My husband voluntarily joined the Communist Party, he was an idealist: I remember he was fond of the book, Marx’s Youth. I joined the Communist Party as well, simply because my husband wanted me to: I wasn’t keen on politics. But I figured that our schedules would match, he would go to his party meeting, and I to mine, so I joined, since it was so important to him. We had to participate in marches on 23rd August 7, it was compulsory, you could find yourself in trouble if you refused; I was a secretary, and I had access to some relatively secret or important documents, so I couldn’t refuse. My husband and I participated in party meetings, and he took the floor sometimes, but I never did.

We left Electrica and Brasov in 1948, when my husband was transferred with work to Bucharest. He worked at a rubber plant, in charge of the financial division, which belonged to the Ministry of Chemistry. In Bucharest we received an apartment, and we stayed there for about a year.

I worked for a while at the Ministry of External Affairs, also as a secretary, until my son, Cornel Menzel, was born in 1949. We left when Cornel was ten months old. Cornel didn’t have a bar mitzvah. He wasn’t interested in religion or tradition at all; he identifies himself as a Jew, but that's all.

My mother was with us in Bucharest all this time: she had been there for a while, raising Angela’s daughter, Doina, because she had moved to Bucharest with her husband. After we moved there, my mother took care of Cornel. My mother died in Bucharest in 1980, and she was cremated, it was her wish before she died, so I respected that.

I was working in Bucharest when I heard about the birth of the State of Israel 8. I was happy; I think every Jew in the world was. The wars there affected me as well; it affects me if they cut a finger off of an Israeli soldier.

After Bucharest we moved to Tarnaveni [town located in Tarnavelor Plateau, on the banks of the river Tarnava Mica], because of my husband’s work again. I didn’t work there, I only took care of Cornel, but the conditions were terrible. We lived in a colony, and we had no running water, I had to keep a servant to help me fetch it and so on. Moreover, the environment was toxic, there were calcium carbide plants all around us. Cornel fell ill, and we eventually had to go back to Brasov.

A friend of my husband’s, Stern, a Jew who was an activist, helped him get a job at Steagu [Steagu Rosu: Red Flag plant in Brasov that manufactures trucks], so eventually we came back to Brasov and we stayed here. Again I got a job as a typist and as a secretary at the cooperative Sarguinta. I never had problems at work because of being a Jew, and neither did my husband. We first rented a furnished room in town, and then a one-room apartment in the same house. My mother-in-law didn’t want us to live with them, she said it was better for the young to stay separate from the old, to start fresh, and she was very right.

There was a funny incident when we moved back to Brasov: I was always late for the party meetings, because I had a child at home, and after work I ran home to check on him. There was a party secretary, Mr. Sas, who was a Hungarian, and when the meetings started, he usually took the floor and started to criticize the ‘unworthy’ members. Once, he wanted to reprove me for being late, and instead of saying, ‘Mrs. Menzel never comes on a regular basis!’ [in Romanian: ‘Dna Menzel nu vine niciodata regulat!’], he said, ‘Mrs. Menzel never comes regulated!’ [In Romanian: ‘Dna Menzel nu vine niciodata regulata!’; a play on words, caused by a mistake common to the Hungarian native speakers, who decline the Romanian adverb as an adjective]. He was the laughing stock of the meeting, and his words were a joke remembered there for many years!

We never thought of emigrating to Israel, because of the climate. My piano teacher from Brasov, who was a Jew and an artist, went to Israel and had to come back as the climate gave her asthma. My husband couldn’t stand the heat, and anyway, none of us knew the language.

Our circle of friends were mostly Jews, and friends of my husband; he had had a lot of friends! I remember going with another couple to Harghita [spa located in the vicinity of the Harghita Mountains], just after the war ended, and pulling in at an inn there. Back then inflation was still high, and it was hard to find all the food you needed. The innkeeper served us with roasted sucking pig, a delicacy we had never had until then, because we ate kosher food in Iasi, and later because it was hard, actually impossible to find on the market! Anyway, we ate it. After the war we couldn’t keep kosher anymore.

My son studied for three years at the Construction Institute in Bucharest. He didn’t complete the course, because we insisted on having him in Brasov, but in order to attend the courses of the Polytechnic here, he had to take six more exams, and he didn’t want to. He stayed at home for a year, but he worked, doing translations from German into Romanian for somebody. He also had a certificate of foreign commerce from Bucharest. He emigrated to the USA in 1975; he had to spend some time in Paris first, I don’t know exactly why, because of emigration regulations, and then he went to Philadelphia.

Cornel lives with a woman named Erika, who isn't American; I think she's of German or Hungarian origin, or both. My sister, Angela, met her, and that's what she thought. I never met her. Cornel has never come back since he left, he was afraid he would give us too many emotions our health didn’t need. After Zoltan died, in 1999, Erika started to write to me a bit, a postcard and so on. I never saw a photo of her either, because Cornel told me that she believes that she is not at all photogenic, so she never has her picture taken. I don't think they're married, Cornel never mentioned that to me.

When he first arrived in the USA, he worked at several companies, and now he does something for the government in and around Washington; he travels a lot, but I don’t know exactly what he does. Erika works with him as well now. I never had problems receiving letters, but then again there weren’t so many and they were about family news, not about politics.

My husband and I listened to Radio Free Europe 9, we bought a radio and we took it with us everywhere we went, especially when we went to Covasna, on vacation. We turned it on in the hotel room and listened to it very quietly. I was forbidden to listen to it, of course, but on that occasion we did: I didn’t listen to it much, I didn’t have time. My son, Cornel, did listen a lot, but he was a more relaxed character and didn’t tell us what news he heard.

I never had problems with the Securitate, but I did have one incident with them. A neighbor of mine told me that in this very building was a secret location of the Securitate. A doctor from Sacele [town in Brasov county, 25 km away from the town of Brasov], called Pap, lived on the ground floor; I never knew him, he had moved back to Sacele before we moved into this house, when my parents-in-law died. A man came to ask me all sorts of questions about him and I saw a gun under his coat. I wasn’t afraid, I told the truth that I never met the doctor, and he left.

Apparently they had discovered some writings or documents of his in his house, which were against the regime. When Cornel was on vacation from university, he told me that a Securitate officer had come to him, here in our house and tried to make him become an informer amongst his university colleagues. He refused, of course.

We struggled to get by financially during communism: we could manage because my husband traveled a lot around Stalin county, as Brasov was called back then, and he had his meals and accommodation paid for; so his salary was spent on household expenses. We went to the synagogue during communism, but only on the High Holidays.

Zoltan became more interested in religion as he was getting older, he even went to a minyan on Saturdays. He died in 1999, and I wasn’t happy about how the community handled the funeral, there were some administrative changes inside the community going on back then, and it wasn’t so well taken care of. An old man from the community, Mr. Lazar Bercovici, recited the Kaddish. I was so affected, I broke all connections with our friends, I didn’t write to any of them about his death.

Despite my efforts, I haven’t yet received any help from the government, because of my husband being drafted into forced labor during the war.

Today I occupy my time with the housekeeping, which is rather hard for me now, and a woman from the community comes every Tuesday to help me clean. I send her to do some shopping instead, because I can't go out without somebody to accompany me, I have high blood pressure and diabetes, and I have already fallen once at home, and I don’t want it to happen again in the street.

I also watch TV and read a lot, until late in the night, books, newspapers like Adevarul [The Truth, a left-wing newspaper loyal to the present governing party, the PSD], our Jewish magazine, Realitatea Evreiasca [Jewish Reality] and so on. I don’t go often to the synagogue, not even on the High Holidays, because of my health problems.

Glossary

1 Securitate (in Romanian

DGSP - Directia generala a Securitatii Poporului) General Board of the People's Security. Its structure was established in 1948 with direct participation of Soviet advisors named by the NKVD. The primary purpose was to 'defend all democratic accomplishments and to ensure the security of the Romanian Popular Republic against plots of both domestic and foreign enemies'. Its leader was Pantelimon Bondarenko, later known as Gheorghe Pintilie, a former NKVD agent. It carried out the arrests, physical torture and brutal imprisonment of people who became undesirable for the leaders of the Romanian Communist Party, and also kept the life of ordinary civilians under strict observation.2 Keren Kayemet Leisrael (K

K.L.): Jewish National Fund (JNF) founded in 1901 at the Fifth Zionist Congress in Basel. From its inception, the JNF was charged with the task of fundraising in Jewish communities for the purpose of purchasing land in the Land of Israel to create a homeland for the Jewish people. After 1948 the fund was used to improve and afforest the territories gained. Every Jewish family that wished to help the cause had a JNF money box, called the 'blue box.' They threw in at least one lei each day, while on Sabbath and high holidays they threw in as many lei as candles they lit for that holiday. This is how they partly used to collect the necessary funds. Now these boxes are known worldwide as a symbol of Zionism.3 Lenin (1870-1924)

Pseudonym of Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, the Russian Communist leader. A profound student of Marxism, and a revolutionary in the 1890s. He became the leader of the Bolshevik faction of the Social Democratic Party, whom he led to power in the coup d'état of 25th October 1917. Lenin became head of the Soviet state and retained this post until his death.4 Cuzist

Member of the Romanian fascist organization named after Alexandru C. Cuza, one of the most fervent fascist leaders in Romania, who was known for his ruthless chauvinism and anti-Semitism. Cuza founded the National Christian Defense League, the LANC (Liga Apararii National Crestine), in 1923. The paramilitary troops of the league, called lancierii, wore blue uniforms. The organization published a newspaper entitled Apararea Nationala. In 1935 the LANC merged with the National Agrarian Party, and turned into the National Christian Party, which had a pronounced anti-Semitic program.5 Anti-Jewish laws in Romania

The first anti-Jewish laws were introduced in 1938 by the Goga-Cuza government. Further anti-Jewish laws followed in 1940 and 1941, and the situation was getting gradually worse between 1941-1944 under the Antonescu regime. According to these laws all Jews aged 18-40 living in villages were to be evacuated and concentrated in the capital town of each county. Jews from the region between the Siret and Prut Rivers were transported by wagons to the camps of Targu Jiu, Slobozia, Craiova etc. where they lived and died in misery. More than 40,000 Jews were moved. All rural Jewish property, as well as houses owned by Jews in the city, were confiscated by the state, as part of the 'Romanisation campaign'. Marriages between Jews and Romanians were forbidden from August 1940, Jews were not allowed to have Romanian names, own rural properties, be public employees, lawyers, editors or janitors in public institutions, have a career in the army, own liquor stores, etc. Jewish employees of commercial and industrial enterprises were fired, Jewish doctors could no longer practice and Jews were not allowed to own chemist shops. Jewish students were forbidden to study in Romanian schools.

6 Legionary

Member of the Legion of the Archangel Michael, also known as the Legionary Movement, founded in 1927 by C. Z. Codreanu. This extremist, nationalist, anti-Semitic and xenophobic movement aimed at excluding those whose views on political and racial matters were different from theirs. The Legion was organized in so-called nests, and it practiced mystical rituals, which were regarded as the way to a national spiritual regeneration by the members of the movement. These rituals were based on Romanian folklore and historical traditions. The Legionaries founded the Iron Guard as a terror organization, which carried out terrorist activities and political murders. The political twin of the Legionary Movement was the Totul pentru Tara (Everything for the Fatherland), which represented the movement in parliamentary elections. The followers of the Legionary Movement were recruited from young intellectuals, students, Orthodox clericals and peasants. The movement was banned by King Carol II in 1938.7 23rd August 1944

On that day the Romanian Army switched sides and changed its World War II alliances, which resulted in the state of war against the German Third Reich. The Royal head of the Romanian state, King Michael I, arrested the head of government, Marshal Ion Antonescu, who was unwilling to accept an unconditional surrender to the Allies.8 Creation of the State of Israel

From 1917 Palestine was a British mandate. Also in 1917 the Balfour Declaration was published, which supported the idea of the creation of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Throughout the interwar period, Jews were migrating to Palestine, which caused the conflict with the local Arabs to escalate. On the other hand, British restrictions on immigration sparked increasing opposition to the mandate powers. Immediately after World War II there were increasing numbers of terrorist attacks designed to force Britain to recognize the right of the Jews to their own state. These aspirations provoked the hostile reaction of the Palestinian Arabs and the Arab states. In February 1947 the British foreign minister Ernest Bevin ceded the Palestinian mandate to the UN, which took the decision to divide Palestine into a Jewish section and an Arab section and to create an independent Jewish state. On 14th May 1948 David Ben Gurion proclaimed the creation of the State of Israel. It was recognized immediately by the US and the USSR. On the following day the armies of Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Iraq, Syria and Lebanon attacked Israel, starting a war that continued, with intermissions, until the beginning of 1949 and ended in a truce.9 Radio Free Europe

Radio station launched in 1949 at the instigation of the US government with headquarters in West Germany. The radio broadcast uncensored news and features, produced by Central and Eastern European émigrés, from Munich to countries of the Soviet block. The radio station was jammed behind the Iron Curtain, team members were constantly harassed and several people were killed in terrorist attacks by the KGB. Radio Free Europe played a role in supporting dissident groups, inner resistance and will of freedom in the Eastern and Central European communist countries and thus it contributed to the downfall of the totalitarian regimes of the Soviet block. The headquarters of the radio have been in Prague since 1994.