Faina Minkova

Chernovtsy

Ukraine

Interviewer: Ella Levitskaya

Date of interview: November 2002

Faina Minkova looks young for her years. She is a sociable woman and agreed to tell us about her family. She lives in a two-storied mansion in a quiet neighborhood near the center of town. This mansion used to belong to her father. He received it when he was a KGB officer. There are fruit trees and raspberry bushes in front of the house. Her father was fond of gardening. Faina and her older sister Elizabeth occupy the first floor, and Faina's daughter and her family live on the second floor. They keep their history alive through family photographs and archives.

I know very little about my father's parents. They died when he was young. My grandfather, Yankel Minkov, was born in the town of Krasnoluki, in Belarus in the 1870s. My grandmother, Sarrah Minkova, was the same age as him. She came from a different town, but I have no information about it. They lived in Krasnoluki. My grandfather was a farmer. He kept a few cows. He sold kosher dairy products. My grandmother sold these products at the market twice a week. She had Jewish and Ukrainian clients. My grandparents had eight children. Only four of them survived the war.

My father's brother Aron, born in 1895, was their oldest child. The next one was Zina, born in 1897. My father, Yuzik Minkov, was born in 1911. The youngest, Tania (- her Jewish name was Teibl -) was born in 1915. They were the only ones whom I knew personally. My father had three more sisters: Beilia, born in 1900, Tzypa, born in 1905, and Fania, born in 1909 - (I was named after her) - and one more brother: his name was Pinia and he was born in 1907. All I know about the rest of my father's siblings is what my mother told me. She knew my father's family well. Aron and Zina were her friends. My father was raised in their families, who were my mother's neighbors in Orsha.

One of my relatives, whose mother was my grandfather's cousin, told me that my grandfather was a very difficult and almost unbearable man. My grandmother, who was a nice and kind woman, suffered a lot. If my grandfather didn't like something he would pull the tablecloth of the table with all the dishes and food on it.

My grandparents weren't religious. My father's cousin, who lived in Leningrad, told me about them. She remembered them very well. They observed some traditions, of course. My grandmother cooked traditional food. They celebrated Pesach. My father remembered his father bringing home big bags of matzah before Pesach. One of the Jewish families living in Krasnoluki made matzah. I know for sure that they didn't observe all traditions. My father and his brothers weren't circumcised; they didn't have bar mitzvah, which is one of the basic rules in Jewish religion. My father's family spoke Yiddish.

There were only a few Jewish families in Krasnoluki. There was no synagogue or cheder in town. My father and his sisters studied at the Russian lower secondary school in Krasnoluki. They spoke fluent Russian with no accent. My father also knew Yiddish well, but he didn't know Hebrew.

In 1919, during the Civil War 1, a military unit of the White Guards 2 came to town. All Jews, including my grandmother and her children hid, but my grandfather recalled that he had left his cowshed open. He went back out to lock it and was beaten to death by the Whites. Shortly after his death my grandmother died. My father was 8 years old at the time, and his younger sister Tania was 5.

By that time my father's older brother Aron was already married. He lived with his family in the town of Orsha, on the border of Russia and Belarus. He was a leather specialist. My Aunt Zina and her husband also lived in Orsha. Her husband Gorfinkel, a Jewish man, was a tailor. They had a son. After their parents died my father's sisters and brothers moved to Orsha one after another and got married. My father's sisters were housewives after they got married, and his brother Pinia was a carpenter. My father and his sister Tania were raised in the families of Aron and Zina. Their families weren't religious. They didn't observe any traditions or bar mitzvah. In Orsha my father completed eight years of lower secondary school and started working part-time at the age of 13. He was a shepherd in the Krasnaya Niva commune. He herded cows after school and did his homework in the field.

After finishing lower secondary school my father went to work as a laborer at the bakery in Orsha. He became a Komsomol member 3. He was very active, took part in public life, was fond of progressive revolutionary ideas, and soon became the secretary of the Komsomol unit of the bakery. My father had a very serious attitude towards public activities. The Komsomol unit headed by my father received the 'Red Flag of the Central Committee of Belarus' award for being the best performing Komsomol unit in the country. My father was 18 years old at the time. In 1932 he became secretary of the Komsomol unit of Orsha. From 1932-1933 he studied at the party school. After finishing this school he got a job with the district newspaper of Orsha, Lenin's Call, a communist propaganda newspaper for the struggle against capitalist society and the construction of a new communist society. I think the title of this newspaper speaks for itself.

My mother's parents came from Orsha. My grandfather, Khonia Shyfrinson, was born in Orsha in the 1870s, and my grandmother, Masha Shyfrinson, was born in Orsha in 1881. She came from a very educated and wealthy family. When she was a child her mother, my great-grandmother, had a love affair and ran away with this man to England. My great-grandfather married a childless woman to raise my grandmother. . His second wife's name was Leya. My grandmother was the only child in the family, and her stepmother gave her all her love. My grandmother was a pretty and spoiled girl. The family had a housemaid and my grandmother didn't do any housework. She had classes with a teacher at home. She studied foreign languages, took piano lessons and liked to read. I don't think that my grandmother's family was religious. I don't know how my grandfather met my grandmother. They got married when she was a young girl.

My grandfather sold fruit. He was a wholesale dealer. He had fruit delivered from Pridnestroviye and Odessa region to sell it to locals at wholesale prices. My grandfather wasn't rich, but provided well for his family. They had a big two-storied stone house, with a high porch and columns, in the main street in Orsha. They rented out the first floor, and lived on the second floor. My grandfather and grandmother had six daughters. My grandfather wanted a son, but they never had any boys. Their oldest daughter, Raya, was born in 1904. Then came Tzypa, born in 1906, Rosa, born in 1908, and Slava, born in 1912. My mother, Tzyva, was born in 1916, and her younger sister, Hava, in 1918.

My grandmother didn't work, but she wasn't very fond of housekeeping or bringing up her daughters either. Although she had a housemaid to help her about the house, she still found it hard to find time to raise her six daughters, and read, which was her favorite pastime. When she got married her stepmother Leya moved in with her family. Leya did all the housework and gave all her love and care to my grandmother's daughters.

They were a very caring family. My grandfather was everyone's darling. Of course, my grandmother's daughters loved my grandmother, but they were still closer to my grandfather.

My grandfather was very religious. He went to the synagogue every day. My grandmother didn't join him, not even on Saturdays. They followed the kashrut. My grandmother wasn't fond of cooking My great-grandmother did all the cooking. She cooked traditional Jewish food: chicken broth with dumplings, boiled chicken, gefilte fish and a lot of vegetables. There was a housemaid, but my great grandmother still preferred to do everything by herself. My mother told me that she taught them how to cook. My mother learned how to make all traditional food from my great- grandmother Leya.

They celebrated Sabbath and all Jewish holidays. My great-grandmother lit candles on Sabbath. My grandmother joined the rest of the family for the prayer. My mother told me that they had special dishes for Pesach that they kept in an oak cupboard in the room instead of in the attic, which was the custom among Jewish families. When my mother was little she liked to swing on the door of the cupboard. Once the cupboard fell on her and all dishes broke. My mother said this was the only time in her life when she was strictly punished. There was a big stove in the kitchen, and they did all baking for Pesach at home. There was a group of people that went from house to house at Pesach to make matzah. They had special boards, rolling pins and wheels for making little holes into the matzah. They had all their tools wrapped in clean white cloth. They even had special cloth for washing their tools after work. They rolled out dough and baked matzah. My mother knew the whole process and made matzah herself.

My mother's older sisters were raised religious. A teacher came to teach them Jewish traditions and how to read and write in Yiddish. The rest of the children were growing up after the Revolution of 1917 during the struggle against religion 4. My mother and her sisters Slava and Haya studied at a Russian secondary school. My great- grandmother taught them to write and read Yiddish. After the Revolution they spoke two languages in the family. The older daughters and their parents spoke Yiddish, and the younger daughters spoke Russian. They studied at a Russian school and it was easier for them to communicate in Russian.

Orsha was a fairly big town. Jews constituted a significant part of the population. There were two synagogues. One was a big choral synagogue in the center, the other one a smaller one in the outskirts of town. My mother told me a lot about the town. The majority of Jews were craftsmen. They were tailors and shoemakers, and bakers that made buns and bagels and sold them at the market. Some Jews owned shops. After the Revolution they could only operate in the underground but continued to work. Jews were selling kosher sausage, (chicken and veal) in their stores. Besides Jews they had Russian and Belarus customers.

After the Revolution of 1917 my grandfather began to have problems. The Soviet authorities weren't p[leased with his commercial activities. He was declared a profiteer, who was making money in dishonest manner. My grandfather didn't stop his business, but he had to do it secretly. Private business wasn't allowed, but he had to continue working to be able to feed the family.

I know that were no pogroms against Jews [pogroms in Ukraine] 5 in Orsha. The power switched from the Red Army to the White Guards or Polish Units. There were victims among civilians, but they were incidental deaths for the most part, like people that were shot by stray bullets.

My grandfather was very critical about the Revolution, but not all members of the family shared his views. His daughter Rosa sympathized with Bolshevik ideas and was one of the first young people in Orsha to join the Komsomol. She joined a group of Komsomol members that propagated joining the Komsomol in the surrounding villages. The town of Orsha was located in a swampy area. One had to walk across swamps, where the water went up to one's ankles, to reach a village. During one of those trips Rosa caught a cold that resulted in tuberculosis. When she fell ill the family was spending all their income to get her good doctors and medication. The family became poorer. My grandfather's earnings weren't enough to cover their expenses. My great-grandmother managed to save the family from starving, thanks to her cooking talents and huge efforts. Rosa died in 1925 in spite of all efforts to save her life. She was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Orsha. Jews from Orsha collected money for a gravestone. Rosa's death was a great shock to my great-grandmother. She fell ill with stenocardia and began to have heart problems. She died in 1926. Her death was a blow to my grandmother.

My mother's older sister Raya had left Orsha before Rosa fell ill. She entered a pedagogical school. The family had to support her. After finishing the school Raya worked at a school in Minsk. She married her colleague, a Jewish man, and they had two children. Slava went to study in Kiev. She met her future husband, a Ukrainian man, when she was a student. My grandparents were against her marriage, but she got married nonetheless. She remained in Kiev and didn't keep in touch with her Jewish relatives. Tzypa stayed in Orsha. She married a local Jewish man, and they had two children. She was a housewife. I don't know whether they had a traditional wedding or any other details.

My mother finished secondary school when she was 17 and went to study in Nizhniy Novgorod. Somehow she failed to continue her studies. She worked at a factory for some time and then moved to Moscow. She tried to enter an institute [college] in Moscow. She had a certificate confirming her work experience at the factory, but she was the daughter of a profiteer and was not admitted. My mother returned to Orsha.

She had known my father since he had moved to Orsha after his parents died. They dated for some time and then decided to get married. My mother's parents were against their marriage. They believed my father to be a poor man. Besides, he was a party activist, and my grandfather didn't like that at all. They got married in 1936 anyways. They didn't have a religious wedding. Religious weddings were considered to be vestige of the bourgeois past. My parents had a civil ceremony. My mother said that her bridal gown was made from an old dress of my great- grandmother's. After my parents had a civil wedding ceremony they went to my mother's home. My father loaded her belongings - (a pillow, a blanket and some clothing -) onto a cart. My father worked at the peat deposit in a village near Orsha, and they went to this village to start their married life. They rented a room in a house. In 1937 my sister was born. She was named after our great-grandmother Leya. Her name in Russian was Elizabeth.

The arrests that began in 1937 and lasted until the beginning of the war didn't affect our family. [The interviewee is referring to the so- called Great Terror.] 6 Many of my father's acquaintances and friends were arrested. My mother told me that people were afraid of noises in the evening, such as the (knocking on a door or the sound of an approaching car). My father believed that everything was done on behalf of the Communist Party and thought that Stalin was right. My father was one of the 'ardent communists' as they were called.

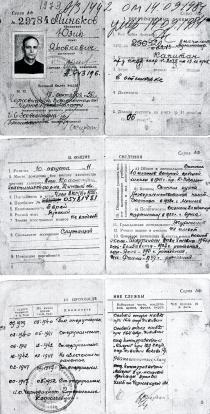

In 1938 my father was sent to the Party's advanced training course for political officers in Mogilyov. He was rarely at home at that time. My mother had a housemaid to help her about the house and with the baby. After his training my father got an assignment with the NKVD 7 Special Department in the army. He became a professional military. This happened before the war with Finland. [the Soviet-Finnish War] 8. My father went to the front. He was wounded and had his toes frost-bitten. He had to stay in hospital for a while. After he was released he got a job in Kamenets-Podolsk in Ukraine. My mother and Elizabeth followed him.

On 22nd June 1941 [when the Great Patriotic War began] 9 my father was taking a course in medical treatment at a sanatorium. My mother and my sister were in Kamenets-Podolsk. My father was taken from the sanatorium to the front. When the air raids began my mother and sister were evacuated as the family of a military. They were allowed to bring two suitcases of luggage. My sister was 4 years old and my mother was eight months pregnant. They were evacuated on trucks. These trucks were bombed on the way. People jumped off the trucks to hide. My mother got off the truck a couple of times, but that was all she could manage to do in her condition. During the air raids that followed she stayed on the truck. Her companions told her to let her daughter run with them to hide, but my mother refused saying that if they were destined to die they would share that fate.

Their initial destination was Khmelnitskiy, but it was already occupied. They stopped at some railroad station on the way to Khmelnitsky. There they were put on a train to Orenburg. In the vicinity of Poltava my mother started to go into labor and had to get off the train. She delivered her baby on the ground near the train. She told me that the baby's back was dirty with soil when she lifted it from the ground. My mother and her baby were taken to hospital, and my sister was taken to a children's home. The luggage with their clothes was left on the train. My mother stayed in hospital for a week. After she was released she went to the children's home to pick up Elizabeth. My mother went to see the commandant of Poltava. She told him that she had had a baby and the commandant took her to a storage facility. He allowed her to take all she needed. This was storage of luggage from people who had been on trains that had been bombed. The commandant helped my mother and the kids to get on the train. My mother named the baby boy Jacob, after my father's father, Yankel. My mother didn't have milk to feed the baby. She told me that she used to wrap a piece of brown bread in gauze, dipped it into water and gave it to Jacob as a pacifier.

When they reached Orenburg my mother met my father's sister Zina at the railway station. Zina had left Orsha at the beginning of the war. Zina told my mother that she, Tania, my father's younger sister, and Fania's daughter Ania had managed to leave Orsha. My father's brother Aron and his family had moved to Podmoscoviye in the early 1930s. My father's other sisters and brother perished in the first days of the war when Orsha was occupied by the fascists.

Zina was heading for Kuibyshev, and my mother and the kids joined her. When they reached Kuibyshev my mother wrote to the evacuation inquiry office in Buguruslan. She found out that my grandparents, Tzypa and her two children, and Haya were in Korkino village, Cheliabinsk region. My mother moved to this village to be with them and went to work. Tzypa's husband was killed at the front. The authorities gave her a cow as aid to the family of a deceased military. Tzypa and my mother got a plot of land where they were growing potatoes. My grandparents had a goat. My mother was a laborer at a canteen and later became an accountant there. She could have her meals in this canteen and so could my sister. When my mother was at work my grandparents looked after the children. They lived in Korkino until 1947.

My father was a political officer and an NKVD employee. He was appointed a SMERSH [acronym for 'Death to Spies', internal security service) division]. But my father wasn't just a clerk sitting in the office. He spent a lot of time at the frontline where he was severely wounded in 1942. He had multiple wounds on his chest, abdomen, arms and legs. He was lying on the ground for over six hours. There was a German sniper on a tree. A star on my father's cap reflected sunrays and the sniper kept shooting until it got dark. Only then my father's comrades got a chance to get him out of there. He was taken to a hospital behind the lines in Baku where he had surgery. It was a miracle that he survived. He had his ribs removed on one side and there were big scars on his chest. He lost a lot of blood. He was in constant pain. There were no analgesics available, and his doctor gave instruction to nurses to give him alcohol anytime he would wake up. Later my father never drank alcohol. He used to say that he had had too much alcohol.

My father stayed in hospital from December 1942 till February 1944. Then he was sent to the Caucasus to complete his treatment. He didn't have any information about his family. He didn't even know about the baby. It took him two years to find his family. He got information in 1944 saying that they were in the Ural. The same year he returned to his military unit at the front. In 1945 my father got an assignment in Japan and then in China. [This was during the war wit Japan.] 10 In 1947 my father was sent to fight the enemies of the Soviet regime in Chernovtsy, Western Ukraine. They were Ukrainian patriots.

Zina and her family stayed in Kuibyshev after the war. Her husband returned from the front. Zina died in Kuibyshev in the 1970s. Her son lives in Israel. Aron and his family lived in Podmoscoviye. His only son Jacob, named after my grandfather, was killed at the front. One of his daughters died of tuberculosis after the war. Two daughters moved to Israel and one lives in Moscow. Aron died in the 1970s. My father's younger sister, Tania, and her husband lived in Zaporozhiye after the war. She married a Russian man and didn't keep in touch with her Jewish relatives. Tania died in 1983.

My mother's parents, Tzypa and her children, and Haya stayed in Korkino. They were the only Jewish family there. They built a house. My grandmother Masha died there in 1959. She had been ill and confined to bed for quite a while before she died. My grandfather died a few years later, in the 1960s. Tzypa didn't remarry. She was an accountant and was raising two sons. Haya lived with us in Chernovtsy for some time. Later, when my grandmother's stenocardia got worse, Haya went to Korkino to look after her. She was an accountant too. She was single and lived with my grandparents and later with Tzypa's son looking after his children. Haya died in 2001, Tzypa in 1984. Raya and her husband moved to Israel in the early 1970s. She died there in 1989.

In the 1950s there were gangs of Ukrainian patriots in the woods of Bukovina fighting against the Soviet regime. This was a mission of the KGB. Ukrainian patriots had their informers in villages. Sometimes KGB units came to a place just a few minutes after a gang had left. KGB was trying to find out who informed the gangs about their plans. It turned out to be one of my father's secretaries, a young girl.

In 1948 my father received a two-storied mansion and a plot of land in a quiet street close to the center of Chernovtsy. It was a cultured European town. There was a university and theaters. Chernovtsy belonged to the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy until 1918. In November 1918 Bukovina became part of Romania. Chernovtsy used to be a Jewish town. When the Romanians came to power some Jews left Chernovtsy. But even then the Jewish population still constituted over 60% of the town. There were about 65,000 Jews out of 105,000 people living in Chernovtsy. Yiddish was spoken in the streets as well as German and Romanian.

My mother and the children moved to Chernovtsy. Ania, my cousin, the daughter of Aunt Fania who perished in Orsha, moved in with them. Ania entered Medical College. My sister and brother went to school. My father grew vegetables and had chickens. Their situation was hard at the time. My mother didn't work and was raising three children. My father ordered my mother to let nobody in when he wasn't at home. People used to bring baskets with food and left them near the door trying to bribe my father. My father took them to the street when he came home. Sometimes aggressive relatives of Ukrainian bandits came to the house threatening to kill the family. It was a horrible time. After all gangs were eliminated my father was transferred to the Chernovtsy regional KGB department.

I was born in November 1949. There were only two ambulance vehicles in town at the time. I was born while the ambulance was on its way to our house. Ania, who was a medical student, was my mother's midwife and cut the umbilical cord. I was named Faina after Fania, my father's sister. I went to kindergarten at 3, and my mother went to work as an accountant. She had learned this profession in evacuation during the war.

My father worked at the KGB office until 1952, when the campaign against cosmopolitans 11 began. Many Jews, including my father, were fired. Of course, he knew why he had been dismissed, and this caused him a lot of suffering. Nevertheless, he remained a devoted communist. He mourned for Stalin in 1953 and didn't believe a word about the denunciation of his cult. We weren't allowed to say a disapproving word about the Soviet regime, or, God forbid, tell a political anecdote. For my father everything about the Party was sacred and certainly not subject to discussion or criticism. He explained that what happened to him was a mere mistake and that it was impossible to avoid such mistakes. My father couldn't get a job for a long time. This was the period of blatant anti-Semitism. The situation was very hard for our family. My mother used to sell our belongings to get food for the family. In the end my father got a job at the human resource department of the woodwork factory. Later he got another job at the Electronmach plant.

In 1954 my mother took me to my grandparents in Korkino. This was the only time I saw them. My grandfather looked like Santa Claus. It was a bitter winter, and he was wearing a heavy white winter-coat. He had a beautiful white beard. He was very handsome, even in his old age. I can't remember my grandmother that well. She had severe stenocardia. She was a fat woman and stayed in bed breathing heavily most of the time. My grandfather did all the housework. He went to buy bread in the mornings while I was still in bed. He always brought me a bagel or candy and put them under my pillow.

We celebrated Soviet holidays at home: 7 November [October Revolution Day] 12, 1st May and Victory Day. My mother cooked fancy food in advance. After the parade we had many guests at home. They were partying and having fun. We also celebrated birthdays and New Year's Eve. We didn't celebrate Jewish holidays in the family. Only in the late 1960s, after my father retired, did we begin to buy matzah and celebrate Pesach.

My parents spoke Yiddish only when they wanted to keep the subject of discussion from us. We didn't learn Yiddish at home. I had a friend whose family spoke Yiddish. I often visited her and learned to understand and speak Yiddish. My sister has a better conduct of Yiddish than I. She also had a friend whose family spoke Yiddish. My brother didn't know Yiddish until recently.

I started school in 1956. I faced direct anti-Semitism from my very first days at school. It was demonstrated by my teacher. She didn't dare to speak openly, but she was very unkind to Jewish pupils. She gave them lower grades and never found any excuse for our minor misconduct. It continued in senior classes. Our tutor, a Jew, continuously reminded us to have teachers put our grades in our record- book, because if we didn't, we might find lower grades in our class registers some time later, and we needed to have our record-book as proof. There were a few teachers that demonstrated anti-Semitism, but there were also Jewish teachers. Of course, Jewish children were the best students. By the time of graduation there were only Jewish children who would get medals for their success. The school management couldn't stand this situation and teachers began to give Jewish children lower grades intentionally. Other children got higher grades than they deserved.

I was a Young Octobrist 13, a pioneer and a Komsomol member at school. I was an active member of all these organizations. I was chief of our pioneer unit, secretary of the Komsomol unit and a member of the school Komsomol bureau. I was also editor of the school wall newspaper. I idolized my father and his view influenced my attitude, I believe. I was fond of mathematics and physics at school. I was fond of mathematic and physics at school. After school my sister entered the Construction Faculty of the Railroad College. Upon graduation she went to work. My brother Jacob entered the Radio-Engineering Faculty at the Radio-Engineering College in Leningrad. Upon graduation he got a job assignment in Nizhniy Novgorod for three years, the (standard term for post-graduate job assignments). When this term was over he returned to Chernovtsy. He got a job at the Electronmach plant where my father was working at the time. Jacob still works there today.

I finished school with a silver medal. Entering university in Chernovtsy was out of the question. None of the Jews stayed in Chernovtsy if they wished to continue their studies. Most of them were going to Russia where anti-Semitism wasn't so strong. I went to Leningrad where our distant relatives lived. I had to pass an interview to be admitted to a higher educational institution. I entered the Faculty of Automated Telecommunications at the Leningrad Polytechnic Communications Institute. There were many Jewish students at our Institute. Most of them came from Ukraine. We didn't have any problems in the course of our studies at this Institute.

Upon graduation I got a job with the telephone agency in Leningrad. This agency was housed in a building in Gertzen Street 14, near the Winter Palace that the revolutionaries were supposed to occupy on Lenin's orders during the Revolution of 1917. At work I constantly faced blatant anti-Semitism. People told me to my face that Jews were a people of traitors and hucksters. I visited Leningrad recently and thought about dropping by my former workplace, but I changed my mind. I recalled the past and realized that such a visit was probably not going to be fun.

When Jews started to move to Israel in the 1970s neither my family nor I had any thoughts about moving to another country. I mean, there were talks about it, but my father nipped them in the bud. He believed people that were leaving to be traitors, and said that nobody should leave this country and that everything here was good and correct. He argued that education was free, and so were medical services, that everything was just fine and if people left it would be a big mistake.

One of my school friends was among the first to leave. There was a special Komsomol meeting at school where she was condemned of treachery. I believed that everybody had the right to make his own decision. If children were leaving their family behind, their parents had to give consent to their emigration in writing. I know that my father would have never given his consent to my departure. I sympathized with these people and envied them a little. They could make a choice in life, I couldn't.

I got married in 1975. I don't feel like talking about my former husband. He was a wicked man, and I don't even want to say his name. He wasn't a Jew, but nationality didn't matter to me. My father raised us as internationalists. In the same year I got married, my daughter Nina was born.

We rented various apartments. When I got a residential stamp in my passport I got enrolled on the list of people wishing to buy apartments. But then I began to feel unwell and my doctor recommended to move to another climatic zone. We got the opportunity to move to the ancient town of Kaluga in Central Russia. I felt better, but I had problems getting a job. As soon as supervisors saw that I was Jewish they rushed to tell me that there was no vacancy available. We took our daughter to my parents' place in Chernovtsy. She went to school there. We didn't know where we were going to live and believed she would be better off with her grandmother rather than share our problems. My father retired in the late 1970s. In 1980 I divorced my husband for quite a few reasons, but I don't feel like talking about it. In 1984, after my father died, I moved to Chernovtsy and lived in my parents' house. I got a job at the Electronmach plant where my father had worked and my brother was working. My mother was a pensioner helping me to raise my daughter. She grew vegetables and did the housework. She died in 1992.

My daughter studied at a Ukrainian secondary school close to our house in Chernovtsy. When Nina was in the 8th grade, this school became a mathematical lyceum. Nina did very well at school and spent all her time studying. She didn't care about public activities. She felt ironic about them. In her senior classes she took part in many mathematical contests and received many awards and diplomas, including international awards. After school Nina entered the Faculty of Applied mathematicMathematics at the University in Chernovtsy. She didn't have to pass entrance exams; she was admitted on the results of her interview. Nina is a teacher of mathematicmathematics at the Polytechnic College now.

When it was time for Nina to obtain her passport she stated firmly that she wanted to have her Jewish nationality written in it. I didn't talk her out of it, although I understood how complicated her life was going to be. I'm so happy that this kind of thing belongs to the past now.

Nina studied at school with her future husband. He is Ukrainian and his name is Gennadiy Goncharuk. He entered Medical Academy after school. When they announced that they wanted to get married I didn't care about his nationality. I saw that they were in love and hoped that they would have a happy life together. They have been together for eight years. Gennadiy is a doctor at the district hospital. They have a daughter, Natasha, who was born in 1995. We live in my parents' mansion. My sister and I live on the first floor, and Nina and her family live on the second floor. Nina and her husband are thinking of moving to Israel. Of course, if they decide to go there, my sister and I will follow them. I believe that we might have a better life in Israel. I hope that my children will decide to move there, although I would be a bit afraid to go to another country now. I've lived my life here and the graves of my dear ones are in this land.

In the past decade Jewish life in Ukraine changed dramatically. We began to identify ourselves as Jews. People of other nationalities respect our feelings. I can't imagine anybody calling me 'zhydovka' [kike], an expression I often heard when I was a child and a young girl. Many of our Jewish neighbors moved to other countries. We have more Ukrainian and Russian neighbors. We get along with them well. I believe the fact that they use the word 'Jew' without feeling embarrassed about it indicates a positive change. People tried to avoid saying this word in the past.

My Ukrainian neighbor was appointed director of the Jewish school. Her grandson goes to this school and studies Jewish religion and traditions. His favorite subject is Hebrew. When he comes to see us and finds that I do something wrong, that is, non-compliant with Jewish traditions, like cooking meat with cheese he points out to me, 'We, Jews, do it in a different way'.

In recent years I've never heard anything bad being said about our family, or Jews in general. I believe that the situation is stable, although who knows? If there were a pogrom I don't know who of our neighbors would come first to rob us, if not kill us. There are such people, although they belong to an older generation. Young people aren't anti-Semitic. We read Jewish newspapers regularly. My granddaughter goes to the dancing and art club of Hesed. I attend lectures on the history of Jewish people and religion. Regretfully, I don't have time to attend all Hesed events.

I've never been interested in politics and never belonged to any party or movement. All I wanted was to have a peaceful and quiet life. We don't go to the synagogue, don't know any prayers and thus don't pray. I believe it's characteristic for most Jews that grew up during the Soviet regime. But we celebrate Jewish holidays at home. We observe traditions and cook traditional food. I make hamantashen at Purim. We cook traditional food at Pesach and make many things from matzah. Unfortunately, there isn't much that we can afford, but we make the best of what we have. Of course, it would be good to have a table laid in accordance with all Jewish traditions, but we think it more important to feed our souls.

Glossary