Evgenia Ershova

Kiev

Ukraine

Interviewer: Zhanna Litinskaya

Date of interview: July 2002

My family background

Growing up

During the war

Post-war

Glossary

My father's father, Ioyl Gutianskiy, was born in the town of Krasnoye, in Vinnitsa province, Ukraine around 1870. The town of Krasnoye was a typical provincial little town with a Jewish and Ukrainian population. The Jews were traditionally craftsmen and the Ukrainians were farmers. They were good neighbors and didn't have any conflicts. I don't know the name of my father's grandfather, but I know that he was a cabinetmaker and his son, my grandfather Ioyl, followed in his footsteps. My grandfather attended cheder, like all the other Jewish boys, and this was all the education he received. My grandfather had brothers and sisters, but I don't know anything about them. I don't even know their names. His family was very poor and my grandfather Ioyl left his home when he was around 14 to look for work. He traveled from town to town looking for work. He stayed in a town long enough to do any repair work he could find, and upon finishing it he moved on. He sometimes came home to bring the money that he had earned, and stayed home for a while. He stayed in the town of Ladyzhin longer than in the others. He liked the daughter of a shoemaker for whom he was working. Her name was Buzia. Buzia also fell in love with the young cabinetmaker and they soon married. Buzia's father, the shoemaker, wasn't a wealthy man, and Ioyl's parents weren't either, but their children had a traditional Jewish wedding. The bride and bridegroom stood under the huppah and the orchestra played traditional music. They had guests from Ladyzhin and from the town of Krasnoye from where the bridegroom's family came. After the wedding the young couple settled down in Buzia's father's house. Ioyl opened a carpenter's shop in Ladyzhin. Buzia's younger brothers helped him in the shop.

Ladyzhin was a real Jewish town. Its inhabitants were shoemakers, tailors, hat makers, roofers and merchants who owned several stores. There was a synagogue in the town. My grandfather went there on Saturdays. They followed the laws of kashrut, honored the Sabbath and celebrated Jewish holidays. But they were not very religious. They paid tribute to the cultural traditions rather than to religion. They raised their children as Jews. The boys were circumcised and went to cheder. At age 13 the boys had their bar mitzvah and at age 12 their daughter had her bat mitzvah, in accordance with the Jewish rituals for the coming of age of boys and girls. I need to say here that my grandparents' children were not at all religious. They observed Jewish traditions while living with their parents, but they forgot about the traditions and holidays after leaving their parents' home.

All of them except for Grisha, the middle son, had high expectations that the Revolution would improve their lives. I don't know anything about the Jewish pogroms in Ladyzhin; at least, we never discussed this subject in our family. My grandfather Ioyl died from a lung disease around 1915. Their children went to bigger towns looking for work after the Revolution. My grandmother Buzia stayed on in Ladyzhin, and spent the last years of her life with her daughter Fania in Kiev. Fania, my grandmother and our family were in the evacuation together. I remember very little of her. She was very old and stayed in bed all the time. She died in Sverdlovsk in 1943.

Their oldest son, Boris, was born in 1894. He graduated from a Jewish elementary school and went to Kiev after the Revolution. Many schools were opened for young people from poor families in Kiev, Kharkov and a number of bigger towns. Young people from the smaller Jewish towns moved to the bigger towns to get an education. Boris took a course in teaching practices and then studied at the Pedagogical Institute. Boris worked at the orphanage for retarded children for many years. He was a wonderful teacher. He didn't have any children of his own. Boris and his wife Olga were in the evacuation during the war. After the war they returned to Kiev. Boris died in the early 1950s.

Grigory, or Gershl, born in 1895, was their next son. In 1918 he moved to the USA. He disliked the idea of building communism. He lived in Philadelphia and got married there. His daughter was born 1927. He opened a stationery store in the early 1920s. His business was successful and Grigory became a wealthy man. During the famine 1 in Ukraine in 1933 he sent my father parcels and money and my parents could buy food in the Torgsin store 2. I don't know whether any member of our family had problems related to Grigory's departure to the USA. I don't think there were any problems, and I don't know anyone who suffered from keeping in touch with relatives abroad. Grigory also sent us parcels after the war. He died in the mid-1980s.

My father's sister Fania, born in 1897, was the closest to our family. She went to elementary school for a few years and then studied at home. She passed entrance exams to the 6th grade of Odessa grammar school and graduated with the diploma of primary school teacher. After the Revolution Fania graduated from the Faculty of Mathematics of Odessa University. Fania got married. She lived in the town of Beshad with her husband. In the early 1930s she divorced her husband and came to Kiev with her son Victor. Victor went to the front during the first days of the war and perished at the very beginning of the war. After the evacuation Fania returned to Kiev. She died in 1964.

My father's younger brother Veniamin Gutianskiy, born around 1907, graduated from the Faculty of Literature in Moscow and became a Jewish children's writer. He wrote poems and short stories for children in Yiddish and in Russian. He lived in Kiev. In the mid-1930s a few books of his poems and stories for children in Yiddish were published. During World War II Veniamin and his wife Bertha were in the evacuation. Veniamin wasn't recruited to the army due to a lung disease. Their daughter Luba was born while they were in evacuation. After the war Bertha worked at the Institute of Literature in Kiev and Veniamin continued his writing. However, he wasn't published then. He was arrested in 1949, during the outburst of anti- Semitism, on charges of Zionistic propaganda. His wife Bertha was also arrested on a fabricated accusation. Their youngest daughter, Maria, was born in jail. Some time later they were exiled to Semipalatinsk, in the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic. Bertha's mother and Luba went there too. Veniamin didn't live long. In jail he fell ill with tuberculosis and died in Semipalatinsk in 1953. In 1956 Bertha and her children returned to Kiev. They had received documents of rehabilitation for herself and her husband Veniamin. Bertha and her children lived with us for some time, because they had lost their previous apartment. In 1957 Bertha received a small two-room apartment. Bertha died in 1972. Her daughters live in the USA.

My father, Leiba Gutianskiy, was born in Ladyzhin on September 27, 1901. He changed his name to Lev during the Soviet era. He finished cheder and then the Jewish elementary school, like all the other boys in the family. Later, my father became a laborer at the sugar factory not far from Ladyzhin. Subsequently, he became a clerk at this same factory. After the Revolution he finished a course in accounting and continued to work as an accountant at this same factory.

I know very little about my mother's parents. My mother was a very withdrawn person and told me more about my father's parents rather than about her own. My mother came from the town of Sobolevka in the Vinnitsa province of Ukraine. My grandfather's name was Motel Trahtenberg and my grandmother's name was Genia. I was named after her. I don't know what my grandfather did for a living. I believe he was a craftsman like my grandfather Ioyl. Motel and Genia were born around 1860. From what my mother told me, I believe their family was rather religious. My mother used to say, 'they were like everybody else in the town.' This means that they went to synagogue once a week, followed the laws of kashrut, honored the Sabbath and celebrated all Jewish holidays. They lived a rather modest life, like my father's parents. My grandfather Motel died before the Revolution of 1917. My mother said it was a good thing that he didn't live to see what was happening in the town during the Revolution and the Civil War [1918-1921]: gangs 3, murder and Jewish pogroms. My mother and her sisters often hid in fields, sheds or haystacks waiting for the bandits to leave the town. My grandmother Genia wept and worried while hiding in town. She didn't know whether she would ever see her daughters again. She died in 1919.

My mother's oldest sister, Luba, was born in 1885. Luba, her husband and daughters Manya and Fira lived in Gaisin, Vinnitsa region. I don't know her husband's name. He died before the war. Because the Vinnitsa region was occupied from the first days of the war, Luba and her daughters couldn't go to the evacuation and had to stay in Gaisin, in the ghetto. During the war the Romanians were the masters of the Vinnitsa region, but they were very hard on Jews, demanding money and gold from them in exchange for their lives. Luba and Manya survived in the ghetto until the Soviet troops liberated them, but Fira died at the end of 1943, some time before liberation. Luba didn't live long after the war. She died in 1948. Manya and her family left for Israel in the early 1970s. I have no information about her present whereabouts.

My mother's younger sister Hontsia, born in 1905, finished elementary school in Sobolevka. Around 1930 she went to Moscow and entered the Pedagogical Institute. In Moscow she married a Russian man from Yaroslavl and moved to Yaroslavl with him. Her parents respected her choice and didn't have anything against this marriage. Hontsia was a primary school teacher. Her son Arkadiy lives in Yaroslavl. Hontsia died in the mid-1980s.

My mother had another sister, named Zlata. I don't know whether she was my mother's younger or older sister. We have a photograph of my mother with Hontsia and Zlata. I know that after she got married Zlata lived somewhere in the Vinnitsa region. During the war she and her children, along with other Jews of their town, were shot by the fascists. My mother was a reserved and tight-lipped woman. She never told me about them. It was probably emotionally too hard for her to talk about her sister. My mother also had a brother. His name was Iosif and he perished during the Civil War.

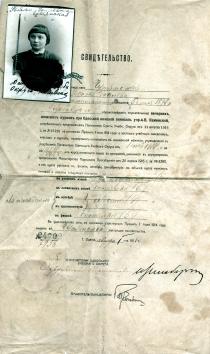

My mother was born in 1903. She finished her studies at the four-year Jewish elementary school and then probably studied with private teachers. My mother didn't have any certificates or diplomas, but she wrote very well in Russian and read a lot. I don't think my grandparents had other books besides religious ones at home. I guess my mother must have borrowed books from her friends or from the library.

My parents met in Sobolevka around 1925 while my father was there on a business trip. There were quite a few sugar factories in Vinnitsa. Almost every town or village had one, and my father often visited there on business. There was also a sugar factory in Sobolevka. I don't know any details of my parents' meeting each other, but I know that they married in 1928. They had written letters to each other for three years and saw each other quite often. My father traveled to Sobolevka almost every month. They had a civil registration ceremony in Sobolevka. They didn't have a wedding party. The three of them just had dinner: my mother, father and Hontsia. There were no other relatives in Sobolevka left. My father had quit his job by then and they left for Kiev. They decided to begin a new life in a big city.

My parents rented two rooms in a house in Demeyevka [neighborhood in Kiev]. My father got a job as an accountant at the Krasny Rezinschik rubber plant. He worked there until the war began. In 1929 my older sister Eleonora (Ella) was born. My mother stayed at home in the first years of her marriage. She did the housework and looked after my sister. Ella was a weak and sickly child. In the early 1930s my father's sister Fania, her son and my grandmother Buzia came to live with us. By that time my father had purchased this apartment from his landlords. My parents and Ella lived in a smaller room and the bigger one was occupied by Fania and her son and my grandmother. Aunt Fania told me that they lived as a big family. The rooms were small and poorly furnished, and the family was not very wealthy. Only my father and Fania worked. There was a flower and kitchen garden near the house. My mother grew flowers and vegetables. Sometimes my father's brothers Boris and Veniamin visited us. Sometimes we visited them. We celebrated family holidays together, birthdays and anniversaries, and we celebrated state holidays like the 1st of May and October Revolution Day 4. These revolutionary holidays were days off and we had the table covered with a fancy tablecloth and there were lace coverlets on the armchairs. It made the atmosphere very bright and festive. My grandmother Buzia did complain that the family didn't celebrate Jewish holidays, but my parents held firmly against this and didn't give in. They even spoke Russian at home, and not their mother tongue, Yiddish. However, they respected my grandmother Buzia and her faith. She tried to keep traditions at home: she lit Sabbath candles in her room, celebrated Pesach and the main Jewish holidays and fasted at Yom Kippur. She didn't try to teach us Jewish traditions against our parents' will. We were young and didn't understand what she was doing; we even laughed at her sometimes.

I was born on August 20, 1937. My sister Ella went to school that same year. My Aunt Fania told me that I was born in a bad year. It was 1937, the year of arrests 5 and repression of innocent people. A few people were arrested at the factory where my father worked and he expected his own arrest every day. Fortunately, he survived the ordeal. I remember very little of my prewar childhood. I don't remember how the war began. My father wasn't recruited into the army. He had a white chit for his poor eyesight.

I have memories of the evacuation. We were in a long railroad car where there was no room to move. We evacuated in the summer of 1941 with the Krasny Rezinschik plant where my father worked. It was very hot. We were thirsty all the time. My mother and father took turns getting off the train at the stations to fetch us water. I fell ill with measles on the way. My mother was afraid that we would be ordered to get off the train due to this infectious disease, and she hid me behind the suitcases. Our trip lasted a long time. As we were crossing the Volga River on a barge my sister Ella fell into the water. She couldn't swim, but she managed to stay afloat on the surface until the sailors from the barge came to her rescue. She got pneumonia afterwards and didn't go to school for a year.

Our destination was Sverdlovsk. The employees of the plant and their families were accommodated in the barracks. My father, mother, my sister, Fania, grandmother and I shared one room. My father was an accountant at the plant. In 1942 he volunteered to go to the front. He had a very hard job. There were thefts at the plant and he was given forged papers for his signature. He didn't sign them. He began to be persecuted at work and one day he said to my mother: 'Rather than work with those swindlers I'll go to the front to defend my children.' In 1942 all men were recruited regardless of their health conditions. My father was shortsighted, but he was made a machine gun man. He wrote us several letters, but then no letters came in 1943 and at the end of the year we received notification of his death. I remember my mother, my grandmother and my sister crying. I didn't understand why they were crying. I couldn't understand the words 'perished' or 'died' at that time. This was the first death in my life, and I was just 6 years old.

Our life during the evacuation was very hard. After my father perished my mother went to work at the Krasny rezinschik plant. She worked at the shop where they made boots for the army. My sister went to school. After classes she worked at the plant packing shells into boxes. She received a worker's card for 400 grams of bread for her work. There was nothing Jewish in our life at that time. We were an ordinary Soviet family suffering from the horrors of war. I went to kindergarten. I stayed there six days a week and on Saturdays I was taken to stay overnight at home and was taken back to kindergarten on Sunday evenings. We had good meals there and I even looked plump, but I remember feeling constant hunger. I woke up hungry in the morning and I went to bed hungry in the evening. When my mother was coming back from work she passed my kindergarten. Sometimes mother managed to exchange some food at the plant's canteen for the boot blanks that she brought to me. Most often it was a whole bucket of vermicelli and something like butter in it. I was waiting for her with a spoon. I remember standing there looking for my mother. She came and sat me on the windowsill and I ate vermicelli from the bucket. It seemed so delicious to me.

In 1943, almost immediately after we received notification of my father's death, my grandmother died. I wasn't at the funeral and didn't see how she was buried. I don't think there was somebody to read the Jewish mourning prayer on her grave.

I remember Victory Day, May 9, 1945. My mother came to the kindergarten. She was kissing me, crying and laughing. I didn't understand why she was crying when she ought to have been merry and happy. We returned home with the plant in December 1945. We went back by freight train. Many families were returning to Kiev, but others stayed in Sverdlovsk. Kiev was in ruins. Many people had no place to live. Many houses were destroyed and many apartments were occupied by other people. Our apartment in Demeyevka was also occupied. Fania, whose son Victor had perished during the war, lived at my uncle Boris' apartment. We settled down in the hostel of the Krasny Rezinschik. We shared a 12 square meter room with another family, a woman and her two daughters. After the war my uncle Grigory sent us parcels from America containing incredible kapron stockings, shoes and coats for Ella and me. It often happened that our neighbors took away all the clothes while my mother was at work and Ella and I were at school. My mother sold some of the clothes. It was a big help for us. At that time a loaf of brown bread cost 100 rubles at the market.

My sister wanted to get our apartment back. She submitted her appeal to the judge and she even wrote to Kaganovich 6. As a result, within two days we received one room of the two that we had before the war. The family of Kashmelyuks that had occupied our apartment continued to live in the other room. They lived there until they finished the construction of a small house not far from where we lived. We got along with this family. We all suffered from the war. Kashmelyuk's son was shot during the war. He was a partisan messenger and he was shot at Babi Yar. 7 After exterminating the Jewish population, the Germans shot communists, prisoners-of-war, partisans, etc., at Babi Yar.

My mother continued working at the plant, but fell ill with cancer in 1963. She died in 1964. My sister Ella entered the Faculty of Philology at Kiev State University in 1948. This was the last year that Jews were admitted to higher educational institutions. Upon graduation my sister went to work in the town of Kuzmina Greblia in the Cherkassy region. She worked there for many years as a teacher of Russian language and literature at the secondary school. She organized a folk choir and an amateur theater. She returned to Kiev in 1970. Eleonora wasn't married and had no children. She died from cancer in 1994.

After the war I studied at the Russian secondary school. I was a Soviet child, went to the May Day parades, collected paper wastes (this was a popular pioneer activity) and was a Komsomol 8 member. It wasn't that I liked it extremely, but it was the only life we knew, and we couldn't imagine a different life. Life around us was poor and miserable and there was no opportunity to change anything. We were assured that life was going to improve and that we only had to be patient. We didn't know that our leaders, their families and their children had a very different lifestyle with the abundance of everything one could dream of. In summer I went to pioneer camps near Kiev. I liked it there. We had lots of fun despite the strict discipline and lining up twice a day. We marched singing patriotic songs. In the first years at school we Jewish children didn't feel any prejudicial attitudes towards us. We were all children of war. Many of us lost our fathers to the war and many children lost their parents in Babi Yar. Our teachers sympathized with us. In the early 1950s during the outburst of anti-Semitic campaigns and during the period of the Doctors' Plot 9 my Uncle Veniamin was arrested and sent into exile. At this time, my history teacher's attitude towards me became abusive. He gave me lower marks and asked me questions that were beyond our school program to give me a '2'[this is almost the lowest grade]. I guess he knew that my uncle had been arrested and this explains his attitude towards me.

In 1953 Stalin died and people wept at the news. The director of our school came to our class with a mourning band on her arm. Classes were cancelled and all the children went outside wearing black armbands. Veniamin's sister Fania did not cry. She always believed Stalin to be guilty for the arrest and death of her brother.

After finishing school in 1954 I went to work as a laborer at the glass factory. I didn't even consider going to university. It was almost impossible for a Jew to enter the university. Besides, I wasn't very successful at school with my studies. In addition, we were very poor and I understood that I had to go to work to earn money. Later, I finished a course for radio operators and got a job at the military unit. I met Valeriy Ershov there. He was a sergeant, a Russian, a very nice and kind man. We fell in love and got married in 1961. Neither my parents nor Valeriy's relatives were opposed to our marrying. We loved each other and this was important to our families. We didn't have a wedding ceremony. We didn't even have wedding rings. In 1963 Aunt Fania, who was very ill, had a premonition of her approaching death and gave us some tsarist golden coins and we had wedding rings made from them. Valeriy came from Gorky. He was an only son. His father Sergey had perished at the front. His mother lived in Gorky. She was a nice, quiet woman. I got along well with her. We visited her several times and she came to see us. She died in Gorky in 1974. After finishing school Valeriy served in the army in Kiev and remained in the military after his term of service was over. He worked as an electrician at Kievenergo. We worked for over 25 years at this plant until it was closed in the 1990s. There was no financing and people were not paid for their work. We retired in 1992.

We have two sons. Yuri was born in 1963 and Sergey was born in 1967. Both of my sons had Russian as their nationality in their passports. It was the only possible way for them to have no obstacles in entering university. They both studied at the Ship-Building College and then enrolled in the Institute of Water Transport in Leningrad. They studied there by correspondence. They didn't finish their studies at the Institute. It was difficult to study by correspondence and they quit. Yuri works at the security guard company. He installs security alarm systems. Sergey is manager at a commercial company. Both of my sons married Russian girls. Yuri married Alyona and Sergey married Oksana. Yuri divorced Alyona a few years ago. They have two children: Andrei, born in 1985 and Valentin, born in 1986. Sergey Egor was born in 1995.

We didn't celebrate Jewish holidays in our family before or after the war. Neither did we have any discussions about our Jewish roots. We never had matzah at home - we were growing up as Soviet children. Therefore, I'm pleasantly surprised that my children, who grew up in mixed families, identify themselves as Jews, although their nationality is written as Russian. Yuri and Sergey both go to synagogue. One day in the 1990s they told us that they had an urge to come back to their Jewish roots. I don't know how they came to this decision. Perhaps, some of their friends practiced religion and influenced them, or perhaps they came to it by themselves. They contribute money to the poor and celebrate Jewish holidays. They are not religious people, but they are trying to restore Jewish traditions in their homes. My older grandson Andrei studied in Israel. His mother insisted on his return recently. She was terrified for her child to stay in a country where terrorist attacks have become routine and where innocent children are targeted for death. Our sons insisted that our family obtain all the necessary documents for emigration to Israel. We did that. But we have delayed our departure for that country, which is actually in a state of war. However, our children do not give up their hope to move to Israel one day. They study Hebrew and attend classes in the Sochnut. We hope that we shall be able to go to Israel soon. We hope that peace will descend upon that country and that we shall be able to move there and not be afraid for our lives and the lives of our children. My husband and I would prefer not to have to emigrate, but as we can't imagine a life far away from our children and grandchildren, whatever our children decide to do, we shall stay with them.

My husband and I are now retired. We are often ill and stay at home. We look after our grandchildren. Sometimes our friends visit us for a cup of tea. We receive a very small pension. Our children and Hesed help us financially. We also receive food packages from Hesed which are very sufficient support for us.