Eva Deutsch

City: Marosvasarhely

Country: Romania

Interviewer: Ildiko Molnar

Date of interview: August 2003

Eva Deutsch is an extremely friendly, warm-hearted and energetic old lady. She has a slim figure and wears simple clothes.

Her husband died in the spring of 2003, and it still feels quite odd for her to live alone in the spacious three-bedroom apartment.

She religiously visits her husband’s grave once a week to lay fresh flowers on it. If she’s at home, she loves to spend her time in the room, which has windows on two sides, looking out into the open.

This is the brightest room, and is exposed to sunlight all day long. The room is livened up by the printed digital photos of her two daughters, her sons-in-law and grandson, sent from Sweden and America.

Even if she lives far away from them, she learns of every little change, not only by phone, but also via the pictures. She is very proud of the ornaments her grandson made for her with his own hands.

- My family background

My paternal grandfather was Lajos Moskovits. He was probably born at the end of the 1860s in Kiralydaroc. I know he had a brother who ended up in Yugoslavia under God-knows-what circumstances. I know that when I was three, that is, in 1929, my parents visited this uncle in Yugoslavia, but I don’t even know the name of the town he lived in.

They took me along, but I don’t remember anything. I only know this happened in 1929 because they came back with some presents: a copper plate and a coffee-set with fancy ornaments – some mosque –, and on the back of the plate was engraved: Sarajevo 1929.

I don’t know what sort of school my grandfather attended, but he didn’t have higher education. I don’t even know whether he went to a religious school. He was a shoemaker by profession. When I grew older and was aware of the situation, he’d already given up his workshop.

He only worked at home, and it was just our acquaintances that came to him for some repairs. As a child I already thought he was old. My grandmother Fani Moskovits was born around 1873. Her maiden name was Majtenyi. I don’t know anything about her parents.

My grandmother didn’t work; she took care of the household. They lived in a small cottage with two rooms and a kitchen, plus a hallway and a small garden that belonged to the house. They had only fowls: geese and ducks. My grandmother used to take care of them.

My grandparents had no interest in politics; people didn’t follow these things back then. But they were religious and used to go to the synagogue, and observed the holidays. They kept a kosher household, partly because it was possible.

Every small settlement had a shochet who butchered the fowls, providing the Jews with kosher food, and Kiralydaroc was no exception. My grandfather had tallit and tefillin, as well, and I think he used to put them on his forehead and his arms.

He used them at the morning and the afternoon prayers. On workdays he used to pray at home. On Friday evenings and on Saturdays they went to the synagogue. They dressed normally, just like other people.

My grandfather didn’t have a black hat, like deeply religious men, but he always wore a kippah. He had no beard, just a moustache; this I remember. My grandmother didn’t wear a wig; she still had her own hair. She always wore a shawl when she went to the synagogue and on Friday evenings, when she lit candles, because she had to wear it when saying the prayer.

We visited them each summer. My father, as a teacher, only went on holiday in the summer, and because there are no Jewish holidays during the summer, we never celebrated the holidays at our grandparents’ place.

They went to the synagogue on Saturdays, attended the ceremony and the prayer, and after that there was no more work. They used to cook the meal for Saturday on Fridays because one wasn’t allowed to work, even to cook, on Saturdays.

On Saturdays we usually had cholent; this was the traditional Saturday meal. They used to put it into a pot on Friday and take it to the bakery and the baker put it in the oven. They went to get it on Saturday and brought back the prepared, hot cholent.

We used to do this in Marosvasarhely, too, because there was a bakery in the neighborhood where we could take the pots. Back then everybody used to make cholent in pots and many took it to a bakery. My grandparents had no help in the household; they took care of everything themselves.

It was a small village my grandparents lived in and in which my parents were born. It was called Kiralydaroc, or Craidorolt in Romanian; this little village was in Szatmar County, between Szatmar and Nagykaroly. It was difficult to reach it because it had no railway station.

The nearest station where the train stopped was at Gilvacs, I don’t know how far away [11 km]. We used to inform them about when we would arrive by mail since we had no telephone, and they used to hire a carriage to wait for us at the station.

A dirt road led to the village and the carriage used to shake us up heartily on the way. Looking back, it was a real adventure, and now traveling isn’t like it was in the 1930s and 1940s.

I remember we went there several times during the holidays, but we couldn’t go there more often. I spent little time at my grandparents’ and that was due to the distance. Back then, Marosvasarhely took a long time to reach. [The distance between Kiralydaroc and Marosvasarhely is 234 km.]

I was 12 when my grandfather died. I didn’t attend the funeral because it was during the winter and it was school time, so only my parents and the local relatives from Szatmar and Nagykaroly were there. My brother and I were left at home in Marosvasarhely.

After my grandfather died, my grandmother remained in Kiralydaroc. She came to stay with us in Marosvasarhely several times, and spent some time with us, but she couldn’t stay calm because she was very curious to see what was going on back home. And there were some relatives living much closer – in Szatmar and Nagykaroly – so she preferred to visit them since they were closer to Kiralydaroc.

The relatives from Nagykaroly, the Majtenyis – the man, Miklos Majtenyi, was my grandmother’s brother – rented a farm, so they were kulaks 1 from the communist point of view. This elderly man had two sons, Bela and Laszlo – my cousins. (Bela, the older one, emigrated to Israel after he returned from the deportation, and because he was still young, he joined the army and then he was killed, the poor fellow.)

They had a horse carriage and set, so they could take my grandmother home. She used to spend more time there when she didn’t want to be alone, and they invited her especially during wintertime to save her heating the house by herself. Back then one could only heat with wood, and had to buy wood, which had to be cut up, and this was a bit difficult.

So they invited her over to spend the winter months with them. When she felt anxious, they took her back home. She came to visit us, too, but for shorter periods. My grandmother’s sister Margit and her family lived in Szatmar.

Her husband was Adolf Roth and they had two daughters, Anna and Kato. The older of the Roth sisters, Anna, visited us once; she was of my age. The family was deported and only Anna came back.

In 1947 she emigrated to the United States and lived in New York. We kept in touch and wrote to each other. She died in 2002. My grandmother Moskovits was also deported [to Auschwitz], and since she was elderly, she was sent to the gas chambers right away. I don’t know anything else about her.

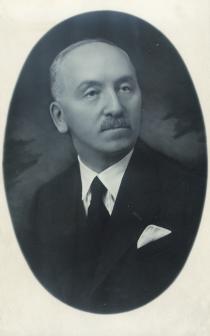

My father, Jeno Moskovits, was born in 1891 in Kiralydaroc as the only child of the family. Unfortunately I don’t know anything about his childhood. He left home at a very early age and graduated from the teacher training college in Budapest before World War I, sometime in the early 1910s.

Then he joined the army and during World War I he fought on the Italian and the Russian fronts. He was a reserve lieutenant there. He was wounded; a bullet flew by his ear and tore off a small part of it. He ended up in hospital. He had some military medals and I think he had four decorations, including a silver medal, and another one called Palmed Military Cross with Swords.

Thanks to these decorations, during the Hungarian times 2, in 1940, when the Hungarians came in and the numerus clausus 3 was already effective, one could have some advantages, such as being put further up admission lists, if one’s father had fought in the war and won decorations.

My father didn’t tell us too much about the teacher training college. I know he graduated with good grades, and after that, when it was the Romanian era after 1918 [following the Trianon Peace Treaty] 4, he had to, as they called it then, nostrificate his diploma.

I don’t know how he arranged to be acknowledged by the Romanian authorities. What I heard is that he was a teacher in some villages nearby, Alsoszopor and Felsoszopor, then he was transferred to Zilah and taught there. He got married in 1920. He and my mother, Jolan Klein, were originally from the same village; he was courting her even before he went to the front. I remember we had quite a few army postcards from that period he’d sent from the battlefield to his parents and to my mother, but after our deportation they disappeared, of course. We, kids, brought them out very often and looked at them because we loved the idea that they came from the front, and that was sensational for us. They had a pinkish color, bore the post-mark on them and were bundled together.

I don’t know much about my mother’s family. I think Kalman Klein, my mother’s father, was a textile merchant. He ran a small store, and I think he had no help there. As far as I know, he traded in textiles. There was no need for larger stores in the village because there were only a few consumers. I don’t even know from what or in which year, he died.

Back then girls used to finish only four years of higher elementary school, and since there was only one elementary school in Kiralydaroc, my mother attended these four years in Satoraljaujhely. As far as I remember she told us her father was already dead then, only her mother was alive.

I don’t know much about my grandmother either. Her maiden name was Hanna Fischer. I guess my mother moved back in with her after she finished school. I don’t know whether they kept the store or not.

I have a booklet about the Jewish community of Kiralydaroc. It was written by Dr. Lajos Herskovits, one of the sons of my grandmother’s sister, Aunt Tilda. I didn’t know my grandmother, only her sister, because she was still alive when I was around 16.

One of her sons became a dentist, he graduated in Prague and lived in Kolozsvar. He was deported, he came back and emigrated to Israel, and there he wrote this booklet about the Jewish families of Kiralydaroc, and sent me a copy, too.

The following is from that booklet: ‘The village is on the two sides of the Kraszna river, linked by one large and two smaller bridges. Like the other villages of the region, Kiralydaroc was a multi-national village.

The right side of the Kraszna was inhabited mostly by Greek Catholic Romanians, while on the left side there lived mostly Hungarians and Swabians, Catholics and Protestants, by religion. The majority of the Jewish community lived on the left side, and the synagogue was built there.

On the other side there were four or five families. These four ethnic communities – apart from minor misunderstandings – lived in harmony as good neighbors. Before the deportations, some thirty [Jewish] families lived in Kiralydaroc.

Mostly people with small incomes, except for two or three wealthier families. The majority were craftsmen and traders, but some of them were farmers. (...) Today there are no Jews living there, only the graveyard shows that this community ever existed, but that too is in an awful condition, and there’s no doubt that sooner or later it will be ploughed up and will disappear, too without a trace.’

My parents were married by a rabbi, but they didn’t talk about the ceremony and there are no photos either. I think when they got married they were already living in Zilah, where my father found himself a job. There was a Jewish school and he taught there.

My older brother Tibor Moskovits was born in Zilah in 1922. There was a vacancy at the Jewish school in Marosvasarhely in 1923 because one of the teachers retired or left, so my father applied for the job. I discovered this in one of his letters.

He got the job, so they moved here, to Marosvasarhely, in 1923 or1924. My father taught everything, just like the elementary school teachers do now, following a class through 1st to 4th grade. He taught Hebrew and music, too, because back in the training school he’d learnt to play the violin. Back then teachers were taught to be multi-faceted and to be good at everything.

- Growing up

I was born in Marosvasarhely in 1926. We rented an apartment near the Jewish school. When I was six, before I started to go to school, my parents bought a small house at the front end of what is now Cuza Voda Street [at the western edge of the main square].

I grew up there and we lived there until the deportation. We were very fond of that house, we constantly did it up. The furniture was simple. The house wasn’t too big, it had three rooms on the ground floor: a parlor, a living room and a bedroom. Above one of the rooms there was an attic room – we loved it –, accessible from the hallway via a wooden staircase.

My brother later moved in and made it his room. I always thought how lucky he was to have a room of his own. I was on very good terms with him, there weren’t any particular problems, despite the four years that separated us. We had a good brother-sister relationship.

There was a beautiful courtyard in front of the house. My parents loved flowers; they arranged the yard very nicely. In the first year an expert arranged it, making flower-beds and planting fruit-trees: apple, pear, plum, cherry and sour cherry; a little bit of everything. We also had red-currant and gooseberry bushes, and lots and lots of flowers.

In the back we had a wood-shed because back then the heating fuel was wood. Each fall we had to purchase it. Collecting the wood was a whole story in itself. I think there were some companies who did this, and we paid them for it. It was quite costly to get all the wood for winter during fall, because one would have wanted to have enough to last until spring.

The wood we bought was carried home, the big trunks were unloaded in front of the house, then the machine sled came – a machine pulled by a donkey – and chopped the wood up into smaller pieces. Then one had to take it into the house because all this took place out in front of the house. Back then the traffic wasn’t as heavy as nowadays, so this could be done.

Finally the saw-dust had to be cleaned up. The logs had to be carried to the wood-shed and arranged. We then cut up these pieces so one could make fire with them in the stove. There was plumbing in the house, I remember we even had a bathroom.

It wasn’t a shiny one like those you see today, but it had a bath-tub, a sink, a flushing closet and tap water. The kitchen had tap water, too, and outside in the yard we had a kind of well. We had a water-hose for watering the flowers and the trees.

Schooling had to be paid for in the Jewish elementary school and the high school I attended. The family had a fixed teacher’s income, and my brother and I were at school, thus school fees for two had to be paid.

Our parents also paid for music tuition; I was taking piano lessons while my brother was studying to play the violin, and they had to pay for that too, as nothing was for free. The household, maintenance and clothing also cost money.

Very few women worked then – teachers or older single girls signed up for work in offices or as typists for lawyers, but these were exceptions, really. Only very few of them graduated from university.

One of the daughters of the rabbi of Marosvasarhely graduated from medical school, probably in Budapest, and became a doctor, a gynecologist even, despite being a woman. This was quite sensational back then. I was still a child and she was already a graduate doctor.

At elementary school the religion classes were taught by a rabbi. There was a rabbi in Marosvasarhely, Dr. Ferenc Lovi. He even had a doctorate. The rabbi was short and was completely grey-haired when I first met him. I don’t know how old he was, but as a child one tends to think grey-haired people are old.

He had a long, white beard, a moustache, but no payes. And he always wore a black suit and instead of a velvet hat he wore a usual civilian black hat. He was a very knowledgeable man, he even had books published, but I don’t know whether those were on religious topics or not.

I think he had three or four children. His family lived near the school, as well. When we became high school students, it was still he who taught us religion classes. Grades were given for this activity.

This discipline was taken very seriously because the trimester school report wasn’t closed until the respective denomination had sent the grades of the students attending the lessons. We loved the rabbi very much and we found everything he said very interesting.

There were stories we believed and accepted, and others we didn’t believe and were skeptical about, for example the things that happened in Paradise and the story of Adam and Eve. Then we used to say, ‘It must be true, though, if uncle rabbi says so, it must be true.’

The rabbi’s apartment was in the front and the classrooms were further back. There were five classrooms all in all, and one room for the teachers. Later a specialized Hebrew teacher was assigned, who was experienced in Ivrit, too. His name was Elek Deutsch, but there’s no relation with my later husband’s family.

He even moved to Israel, but he came back because his wife couldn’t adapt to the climate. They moved back from Israel [still Palestine at that time], then the whole family was deported and none of them survived.

He taught Ivrit in a very efficient way, because we, the students of the Jewish school, had to study it, after all, – I don’t know how many lessons we had weekly, about two, but he was so good at teaching it that we learned to read and write in Ivrit quite well.

Then, as time went by, of course, I forgot it all, and now I don’t remember anything. When I started 1st grade he wasn’t there yet. He came there later and took over the task of teaching Ivrit.

My father became the principal of the Jewish elementary school, and he was a principal-teacher because he taught, too. He didn’t teach me, though. Back then the same teacher followed a class through the four grades, just like today, and my class was assigned another teacher, Ferenc Rado, who started a new 1st-grade class.

There were four teachers at the school, two male and two female, and Mr. Deutsch came as the fifth, but he only taught Ivrit. The two women were Boske Rosenfeld and Ilona Kohn. Only this Ilona Kohn survived the deportation.

After the war she had a higher rank, and she even became a school commissioner. She got married before the war to Erno Salamon. I think he was taken away to forced labor in Russia and never came back. After she returned from the deportation, she remarried.

Back then both elementary school and high school teachers tried to maintain a distance; students respected them very much, and there wasn’t this familiar atmosphere you can see now. Children were treated differently then even within the family, and problems weren’t discussed openly in front of the children, as you see today.

They were never informed if there were difficulties, conflicts or discussions because it was thought it wasn’t suitable for the children to be aware of them. There were no discussions in front of them, and they became adults much later than they do today.

At school the punishments were standing in the corner, pulling the ears and caning the palms – but students were never beaten. The child had to hold out his palms, and the teacher gave them a smack with a ruler or a cane.

The rabbi never punished us, but when he asked us something and one wasn’t too happy to answer, he used to ask, ‘Are you telling the truth? Let’s see!’ Then he used to put his finger one one’s nose saying, ‘Your nose is too soft, you didn’t tell me the truth.’ Then we used to admit that it wasn’t quite that way, it happened otherwise.

At the end of each year we closed the year at the Jewish elementary school with a day-long trip to Somos Hill. This was really a big thing back then. We were always afraid it would rain, and wanted good weather for the trip to be a success.

Everybody had to bring some snacks from home. I remember the school rented a small horse carriage that carried barrels of water to the top so that there was water if anybody got thirsty. In the morning we went to the school first, and from there we went to Somos Hill in one group.

These trips usually ended late in the afternoon. The teacher came along and supervised us. All kinds of activities and games were organized there. We then went back to the school in one group and everybody went home from there. We rarely went to the Somos Hill with the family.

At the end of each school year, class portraits were taken. There was a photographer on the main square called Weintraub, his studio was in one of the courtyards. The school always asked him to take the pictures. It is possible that he was asked because he was a Jewish photographer.

The camera was on a tripod and looked like a big monster. It had a black cover, and we used to laugh a lot when the photographer got under the black cover and then looked out and said, 'Now you must look at me!' - in other words, having a picture taken was quite a ceremony.

We loved going to the Jewish school. I had many girlfriends there and everybody knew everybody, and my classmates and I got used to each other. There were also festivals like Purim, when a Purim ball was organized. This was a holiday, and in the largest classroom – which wasn’t that big though – the desks were put aside, musicians were hired and everybody could dance. The musicians weren’t Jews and they played dance tunes, not religious music.

The students had to bring cakes, cookies, fruits and soda to the Purim balls – there was no Pepsi, Fanta or anything like that, we were quite happy with water. Everybody brought what they could and they put it on a table in another room. That was how the buffet was set up.

I don’t remember whether we had to pay a small fee for the food or if we could eat for free. However, maybe the money we raised had a certain purpose, but I don’t know what it would have been used for. Every class had a presentation of something their teacher had rehearsed with them.

There were students who could sing, others were good at reciting or learning a dance. There were some Jewish dances, but other types of dances, as well. I only remember one kind of Jewish dance, a hora-like 5 one, with people standing in a circle.

We called it Julala. I remember we used to sing this word, and it also had a melody. I remember the Jewish anthem, the Hatikvah 6, we always used to sing it at school. (Nowadays, many times when there is an event at the synagogue, I miss it, but we never sing it.)

These were the special occasions. On Purim we never really dressed up. And there was the tradition for old acquaintances, friends or friends of the family to send each other gifts made from sweets: cookies, cakes, this and that, because back then everybody baked them at home.

There was a common, but very tasty cake called kingli. This is like a poppy-seed roll, but not made with puff pastry, but with a very thin layer of pastry and lots of filling, with raisins and many other delicacies. I know the pastry included honey, but anyway it was a real delicacy. We used to bake several rolls of it since we had to give some to acquaintances and friends. The gift package consisting of all kinds of sweets, was called shelakhmones.

The holiday of Chanukkah was organized at the school with the candlelight burning throughout the eight days of Chanukkah, and we were given small packages – all part of the tradition. Back then this was a holiday and people didn’t have to go to work, and there was no television.

In the family, after we lit the Chanukkah candle, the four of us – including my parents – used to play a game called trenderli [dreidel]. One had to spin a spinning top, which had four Yiddish letters on its four sides – but I don’t know which ones –, meaning whole, half, nothing, and I don’t even know what the fourth one meant. [Editor’s note: the four letters are N, G, H and S. N – neither win or lose, G – win everything, H – win half, S – put one to the pool.]

The package we received on Chanukkah contained the so-called promintzli bonbon, colored in white and red and about the size of an Aspirin. The under side was flat, the upper side a bit pointed. Each person was given a certain amount of these candies, I don’t know how many per person. We spun the spinning top, and depending on the outcome, one had to give one to the bank, won everything, won half or nothing. At least this is how we played it at home.

As far as I remember, we had vacations at Pesach, since the holiday lasted eight days. We made some big preparations for it, we used to do major housecleaning before it. In order to clean the house of bread-crumbs, we had to move the furniture and had to clean everything.

For Pesach we used to buy sugar, matzah flour and margarine, only in packages with the seal ‘Kosher shel Pesach’ on them, from the Jewish grocery. These were packaged strictly in places where there was no bread or any other products made with yeast. It was a tradition to formally sell to a non-Jew any belongings, kitchen utensils and food from the larder, which weren’t right for Pesach. This was only a formality.

One made a formal contract with the neighbor for all these things because there were neighbors one was on good terms with. We had a Christian neighbor. He took nothing away; the two parties only signed a piece of paper. When the holiday was over, they terminated it. The neighbor my parents used to do this with already knew this tradition – because neighbors didn’t change too frequently and we lived in one place for quite a long time.

We had to change the utensils because we weren’t allowed to use those that had ever held bread in them. No matter whether they were washed up or not, we weren’t allowed to use them during Pesach. We didn’t need that many pots, so we could replace them for a week or so, and I know we had a chest in the loft with Pesach utensils: plates, flatware and several pots. On Pesach we got them out. The other utensils had to be gathered in one place.

My father used to lead the seder. It’s a beautiful holiday. On several occasions it wasn’t only the four of us celebrating it because my father sometimes invited people. Once one of our relatives from Szatmar was drafted into the army, and did his military service here.

We invited him for the seder, he got a permission from the camp and celebrated with us. He was a relative on my father’s side and I think his name was Ferenc Domahidi. And there was one of my father’s colleagues from Szaszregen, whose son also did his military service here and came to us on one occasion.

There’s a moment during the seder when the cup must be filled with wine and the door must be opened to let the prophet Elijah come in and drink from it. We, children, always watched the cup – we couldn’t see, of course, the prophet coming in –, and saw how the wine was vanishing. We thought it was fantastic and said, ‘Look, he drank from it, and he is probably gone now he has drunk from it.’ Well, you know how kids are.

Another highlight was when one had to take away the afikoman without being seen by the head of the family. My father wrapped it up and put it somewhere, and while he washed his hands – one should wash his hands several times during this ceremony – either my brother or I took the afikoman.

I was the younger one, so they normally let me steal it. Then negotiations followed for what I would accept in exchange. I don’t remember what I asked for, but it couldn’t have been something really big, because back then children were more modest than today, and were happy with less.

Initially the four questions [the mah nishtanah] were asked by my brother, but later, when I grew older – and we learned it at school –, I asked them in Hebrew. The ceremony was held in Hebrew as well. The prayer book written in Hebrew for the whole ceremony is called Haggadah, and it was translated into Hungarian.

We read this translation and that’s how we understood it. Then we used to sing the original text in Hebrew together. We were only allowed to eat matzah. There were some bitter roots and apples with nuts that looked like mortar. Then we had boiled eggs, which had to be sprinkled with salt water, meat soup with matzah balls, and poultry or beef with potatoes.

My father always followed the religious laws, as he had to, because by his profession he had to show an example. He did it so strictly that on Saturdays we weren’t even allowed to light a fire, nor to switch on the light – and I could never understand this, since it wasn’t a demanding activity, in my opinion.

So when we had a housemaid to help us, she would do these things for us. The housemaids were usually Hungarian girls. Later, when I grew older and we didn’t need any help, it was always a problem on Saturdays to light the gas burner –we already had gas in our home.

We had been connected to the gas main in 1938. We weren’t amongst the first ones to do so, connecting started several years before. After all, what was the big deal in lighting a gas burner? But we weren’t even allowed to do that. We had to sit out by the window and wait for somebody kind enough to light the gas burner or to switch the light on – if one didn’t want to bother the neighbors with it all the time.

Every Friday evening, as soon as the holiday started, the candles were lit. From then on one wasn’t allowed to wash, iron, clean up or do other things like that. I could understand this because these were demanding physical activities and could be called work.

Every Friday evening my mother used to light four candles. I don’t know why four. Not every Saturday, but very often, we had cholent. We really liked it. On Saturdays, when we went to the synagogue, we used to dress up nicely. Women who were already married weren’t allowed into the synagogue bare-headed, they had to wear a hat or a shawl.

In the city women tended to wear hats – only the provincial girls wore shawls –, so there were straw-hats or some lighter hats for the summer, and other types of hats for the winter. Girls and children were allowed in bare-headed. The shawl came into vogue especially after World War II.

Boys had to wear a kippah only from the age of 13, after the bar mitzvah. [Editor’s note: Eva is mistaken here because boys have to wear the kippah from the age of three, and the tefillin after the bar mitzvah. The rules for wearing the tallit depend on the different traditions.]

My brother had a bar mitzvah. As far as I remember, he was prepared by my father because he was quite well informed on religious traditions. He had the materials in Hebrew one had to know from memory, because one wasn’t allowed to read them. I know they prepared quite hard for it.

The ceremony took place in the synagogue in the morning, and I think they asked him some questions. I don’t remember whether it was the rabbi himself because there were other prelates who knew the religious proceedings, too.

The questions were given to him in advance, of course, and he only had to learn the answers. Only men were allowed to stay below, so the women sat in the loft. After the ceremony, close acquaintances and friends were invited to our house. In the morning the adult guests came, while in the afternoon it was my brother’s friends. I think they gave him books as gifts.

In high school, I had to go to school on Saturdays because Saturday was only a holiday at the Jewish elementary school, but there, it was Sunday which was school-day and we went to school on Sundays. There was a so-called French Institute, which we knew as the French Lyceum, a small school because it only had four grades which correspond today to the 5th, 6th, 7th and 8th grades.

It was in 1937-38 or 1938-39 when I ended up in this French Institute. The teacher was a French lady called Madeleine Baciu, who married a Romanian lawyer called Baciu.

On Saturdays we weren’t even allowed to write, of course, and the benefit of this school for the Jewish students – 70 % of the students were Jewish, and some of the very religious Jews sent their children to this school – was that the principal there was very lenient and didn’t force them to write on Saturdays.

For example, test papers were never scheduled for Saturdays. If a Jewish student was asked to the blackboard for repetition and the subject required writing, one could ask a non-Jewish classmate to write on the blackboard what one dictated. On Saturdays, when the teachers explained something, we didn’t write down anything.

We borrowed the copy-book from a classmate or went to his home afterwards and copied up the lessons, so we never fell behind. On Jewish holidays, for example, we were permitted to not to go to school. I mean we wouldn’t usually be absent from school for eight days, but on the major holidays we were.

Only the principal was French, the other teachers were all Romanians. Teaching was very well organized: from the 1st grade we studied French and French literature. In addition, in the 1st grade we studied mathematics and zoology in French, too, so the students became familiar with the numbers and mathematical terminology, as well as the names of animals in French.

The other disciplines were taught in Romanian. In the 2nd grade we learnt botany in French, besides French language, in the 3rd grade, physics and in the 4th grade – which I was unable to attend – chemistry.

Unfortunately I only finished three grades there because when I finished the 3rd grade it was 1940. I didn’t get to use my French and unfortunately I forgot most of it. [Editor’s note: In 1940, following the Second Vienna Dictate, Northern-Transylvania was annexed to Hungary and the region was transferred to Hungarian authority.

Due to these changes the school Eva attended was closed down.] If one finished this school, well, one knew everything in French. Besides school, we had to go to religion classes. We attended them at the Jewish school and we were taught by the rabbi. He then sent our grades to the school. We weren’t allowed to be absent from these lessons, only with certificates of absence, because if you had no grades for religion classes, the school report wouldn’t have been closed.

My parents weren’t really involved in social activities, my father just took part in activities related to his work at school: management meetings or parents’ meetings. He had no duties in the Jewish community, he was only a regular member.

There was an organization of Jewish women here in Marosvasarhely, I think it was called WIZO [Women’s International Zionist Organization], and my mother was a member of it. They organized tea party events that my mother used to attend, and that was about it.

We, kids, were left out of these activities, and we were told, ‘Your duty is to learn, so be obedient...’. And there were girlfriends one could have fun with, and could go here and there with, but there were no big parties or discos.

My parents had both Christian and Jewish acquaintances. We had some very good Christian neighbors, and since we had no relatives in Marosvasarhely, we made friends mostly with our neighbors. They also had some Jewish friends.

They didn’t have too rich a social life, but visited each other. They very rarely went to a restaurant, but every now and then they went to the cinema or the theater. We couldn’t really afford to lead a high life, because we only had one fixed income in the family, unlike a merchant whose income varied from month to month. We had that fixed sum we had to apportion. We were not wealthy.

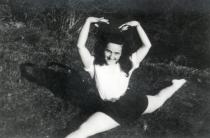

Back then there were movies with child actresses. I was a very good gymnast and dancer, so I got some parts in such movies. I could dance and I even took up ballet. There was a ballet school, and the teacher was called Piroska Szalkay, and one could register there, but a fee had to be paid.

There were many cultural events and charity balls, and the children were asked to play anything they could. There were people who trained them to dance, to do gymnastics, to sing or to recite. I was always asked to dance.

I appeared many times on the main stage of the Culture Palace or in the Transilvania Cinema, on the corner of Bolyai Street, beside the Transilvania Hotel. This cinema was in fact a theatre hall, because it had a stage.

Other performances took place in the Jewish community center, at the Progres cinema. I was invited many times because I was very skilled. Usually the dance and ballet teachers recommended the students they preferred for the representations, and they trained us for these events.

Later, before the war, when I was in high school, we weren’t allowed to go to the cinema, they only let us go to movies when the school organized trips. The teachers decided what movies were suitable for the students to see and only let us see these movies.

I don’t remember any titles, there were these wishy-washy vaudeville musicals, but some educational movies, too. It was arranged with the cinema to make sure that groups from different schools did not go there at the same time, so a certain number of classes from one boys’ school were going there on a certain day to see a specific show, while the girls saw the same movie on another day.

Both the Jewish and non-Jewish students were forbidden to go to the cinema otherwise, even though those weren’t the kind of movies you see today. There were a few who took the risk and went to the cinema, but if seen by a teacher they risked suspension from the school for two or three days.

The punishments were that serious. They were very strict when it came to breaking the school rules. For example, girls weren’t allowed to mix with boys during the school year, and if you were caught, they began asking questions about whom you were with.

In such cases you could have said it was your cousin, but then you would have got a reply like, ‘You have a lot of cousins.’ We had some severe teachers, but some were more lenient, as well.

There was a mikveh in the town, but I never went there. Neither did my mother, because she wasn’t that religious. She observed Jewish religion and holidays and went to the synagogue on holidays, but she never wore a wig. I think there were no more than two shochetim in the town. But I don’t know that for sure because we were Neolog 7, not Orthodox Jews.

Our shochet was somewhere in the back-yard of the building where the Jewish community has its offices today. There was some butchery there; we used to take the fowls to the shochet to have them slaughtered. I don’t know whether the Orthodox Jews had a different slaughterer of their own, or if they used this one as well. There were kosher butcheries where veal and cattle were slaughtered, and one could buy kosher meat there. I remember a Jewish butchery where they only had kosher meat. It was where the Ifjusagi cinema now stands.

This beautiful synagogue we have here in Marosvasarhely already existed, but there was a smaller one, also on Iskola Street, where the parking lot in Szinhaz Square now stands. This was a small Sephardi synagogue, belonging to the very, very religious, but I don’t know when it was built.

It was demolished in the 1960s, when Szinhaz Square was built. There was a third, functional synagogue, a brick building, unfinished from the outside, but with a finished interior. This was the Orthodox synagogue. It’s not a synagogue anymore.

I don’t know much about these things because none of the girlfriends I used to socialize with were Orthodox. We were all Neologs. After the war only the Neolog synagogue was operating. The Orthodox one was already closed.

For a while the community offices were in the building of the Orthodox synagogue, upstairs. There was even a Jewish club there, upstairs, which now, I think, is the headquarters of the Gas Company. This club existed before the deportation, and as far as I know, it was frequented mostly by men, who used to chat and play rummy there.

There were lots of Jewish merchants in Marosvasarhely. In the main square almost every merchant was Jewish. I think there were one or two Romanians and several Hungarians, of course. Among the Jewish ones the Nussbaum Doll and Toy Factory – owned by the Nussbaum brothers – manufactured board games, toy building blocks and toy furniture.

This factory had a store and I used to stand in front of the windows for quite long periods because there were beautiful dolls on display there. And the Mestitzs had a furniture factory here.

- During the War

The troubles began when I was in high school in the 1940s. Life hadn’t changed yet, one could only hear about this and that. But news wasn’t coming in as promptly, as it does today. The newspapers wrote some things, and only a few people had radios.

We only managed to get a small radio in 1940, which was given away very cheaply and it was called Nepradio [People’s Radio]. It couldn’t pick up too many stations, but it was still better than nothing. I don’t quite remember what we listened to, but I think music, some cabaret shows or live coverage of theater performances, and things like that. But then the troubled waters came. I know air-raid warnings became normal and signs of war began to appear.

One could hear about things in Poland, Germany and Austria, but somehow people were so naive they couldn’t imagine what that could bring and what it actually meant. No one believed it would spread until it reached us. As I look back, it seems to me that people were very naive back then.

My parents despaired at what was happening elsewhere. By then the Kristallnacht 8 had already taken place, but I think they never thought that this could touch them and that what happened there might happen to us.

We subscribed to Jewish newspapers, like the Uj Kelet [New East, journal] and a magazine called Mult es Jovo [Past and Future, monthly literature and cultural magazine]. Furthermore, we had a subscription to the local newspaper, I think it was called Maros, which is now called the Nepujsag [People’s Journal]. In the Hungarian times even I could subscribe to a magazine for young girls – I don’t know what it was called, but it was a weekly or a bi-weekly.

Then there were soft-cover highbrow literature books, called Szazszorszep [Daisy] books, which weren’t expensive, so we could afford to buy them. In addition, we registered at the library where we could borrow books because our home library wasn’t very large.

We had a few books of Hungarian literature, including the works of Janos Arany 9 and poems of Jozsef Kiss 10, but we could fit these all on a bookshelf with three shelves. And we could borrow good books from the library, so we had things to read.

There were a few larger bookstores, each with a lending library. One of these was called Erno Revesz, and also belonged to a Jew. It was a large room stretching quite far back: the books to borrow were on one side. One had to register in order to borrow books.

In 1940 I finished the 3rd grade of high school and I was preparing for the 4th grade. The first shock came when not everybody was allowed to attend school. There were many Jewish children here in Marosvasarhely, but not everybody was accepted.

At the start of each year one had to register in the relevant class. After the year was closed it would be announced in which period of the next year one could enrol for the next year. In the Hungarian times, that is, in the period between 1940-1944, it wasn’t that simple to register.

It was established that only 6% of the Jewish children were allowed to go to school, and those who could prove their parents had fought for the Hungarian army in World War I and were decorated, had priority.

Everybody submitted the requests, and those who had relevant documents attached them. Following an evaluation they selected 6% of them and rejected the rest. So, based on a request, and by proving that my father fought in the war and was injured and decorated, I was instantly accepted to the school.

The public high school for girls, as the school was called, was in the building of what is now Petru Maior Technological University. The French Institute was already history in the Hungarian times.

Circumstances had changed and the school was closed down. The principal, a French lady, remained here with her husband and they built a beautiful house in that period. She died here. Due to the strong Hungarian-Italian friendship, Italian language courses were organized. Then one of my girlfriends and I decided to learn Italian, so we began one of these courses, but after two or three lessons they suddenly told us Jews weren’t allowed to attend the course. This was another slap in the face.

In 1940, everybody was happy that the Hungarians came in. My mother had never really managed to learn proper Romanian; she graduated from a Hungarian school. This change was received with great joy. The first anti-Jewish laws in Romania 11 were adopted in 1942 or 1943, and not right away; a series of disappointments came because though it was fine we had this [Hungarian authority once again], the other aspects weren’t quite in our favor.

There were young fellows who, when coming across long-bearded elderly Jews, pulled their beards, made all kinds of remarks and generally made fun of them. Despite all that, my father continued to go to the synagogue every Friday evening and on Saturdays.

I know that after a while, we were really afraid and couldn’t wait for him to come home, and we were always concerned about him getting hurt or attacked. You could never know what would happen if someone saw him at the synagogue, going in or coming out.

In the latter stages a nightly curfew was imposed on us, so we were forbidden to go out into the streets until morning, after a certain hour in the evening. We couldn’t travel so freely either, but people weren’t traveling too much back then anyway.

I had to face an unpleasant situation in school, already in the Hungarian times. There was a Latin teacher, Irenke, a lady who probably didn’t really like Jews. When she wanted to test us by having us explain the lesson, she called four students to the blackboard and there she asked them questions which they had to answer.

I remember I was in such a group of four, in front of the blackboard – I think there was another Jew in the group, too. She asked something which we couldn’t answer, and she got really angry and said, ‘I don’t know why are you here – she was addressing us formally –, why don’t you go to Palestine?’ There was no Jewish state yet, Israel was still called Palestine then.

This really hurt my feelings very much, even though I think she only said it in anger. Then, during the deportation, I used to say with grim humor, ‘What a shame I didn’t take Aunt Irenke’s advice and go to Palestine, then I wouldn’t have ended up here’.

Later, when the Germans came in, but before the deportations, this Aunt Irenke changed radically after she gave birth to a child with a dislocated hip. She had an entirely different attitude towards us, so she changed. That year school ended very early – on 7th April: she talked to us, the Jewish students, like a true educator, comforted and encouraged us when she bid us farewell.

I felt we were undesirable. My brother graduated from high school in 1939 or 1940. He finished Papiu Lyceum. The change took place when the Hungarian army arrived in early September 1940.

As a graduate he decided in the same year he would go to university. Those days there wasn’t this throng for university that you see today; there was no matriculation, only registration. Then he applied for three or four universities in Hungary, I don’t know in which cities.

He was rejected by all of them, so the Jews were already excluded. Sadly, we had to acknowledge this situation. And then, instead of being enrolled in the army, the poor thing was taken away to forced labor. Until then he used to tutor weaker students who needed tutoring in disciplines like mathematics. In 1943 he was taken to forced labor to Palotailva [on the banks of the Maros River, 77 km from Marosvasarhely], but I don’t know what kind of work they had to do there.

In March 1944 he was given a furlough, and came home for a few days, but then he had to go back. That was the last time I saw him. I don’t know where he was taken, but on 23rd August 1944, when the war ended, he and one of his mates set off for home on foot. In that period the Russians were taking away the German prisoners of war and everyone who could, fled from these columns.

The Russians, though, had to account for a certain number of prisoners. If people went missing along the way, they took people from the streets and put them in these columns so they could hand over as many people as they had taken on.

My brother and his friend almost got to Ernye [some 18 km from Marosvasarhely], or somewhere around there, but they met such a group, so they were taken prisoner by the Russians and sent to a camp in the Crimea. Unfortunately this wasn’t an exception, many others had fallen victim to such actions.

I don’t know what they had to do there, but my brother got typhus and passed away in January or February 1945, so he never came home. This I know from his comrade, who eventually came home. (In 1999 I received 30,000 HUF [USD 120] from the Hungarian state as compensation for what happened to my brother.

The Germans came into Marosvasarhely on, or around, 19th March 1944. That year school ended very early and then everything happened very rapidly. Early in April I was still attending the school, and my father was still teaching, when all the schools had to officially end the year simultaneously.

Early in 1944, when the law regarding the obligation to wear the yellow star 12 came into force, the first unofficial news came, that Jews would all be gathered and taken to Transdanubia for agricultural work, but without separating the families. This was the news.

Furthermore, we would only be allowed to take luggage of a certain weight. Everybody began looking for or making backpacks to have something they could pack their things in, so we were somewhat prepared.

Then the official notification came on banners saying we had to be ready by 3rd May with packs of a certain weight, including spare clothes and food, because they would come to take us away.

Everyone prepared themselves and my parents said we would manage. Somehow they weren’t too concerned and they trusted this was just wartime, but we would pull through it somehow and then we would reunite with my brother and would be together again.

That’s how people deluded themselves. We didn’t want to flee to Romania or hide. People were afraid and none of them would take such risks. There were probably one or two people in Marosvasarhely who did it.

I know about cases when the Christian relatives somehow accepted children, declaring them their own, thus saving them. But where could we go? We knew nobody, and nobody trusted anybody. We couldn’t do anything illegal, as we were accustomed to doing everything legally:

if something had to be done this way, we did it, because if we fled, we thought it would be worse for us. People had this feeling of honesty you can rarely find today. People were somehow more honest then and they had more respect for laws and rules.

Each of us had his/her own backpack. We were prepared and dressed because although they told us when they would begin, we couldn’t know when they would reach our street. In the end they came to us, too, and we had to leave the house with everything in it.

We took our documents along, identity cards, my father took his diploma, I took my school certificate, and anything we thought would be helpful. The gendarmes with sickle-feather-hats came for us. The column was quite long on Cuza Voda Street, where we lived, and we had to join it.

There were some carriages there for very old, handicapped or sick people, so people could sit in them if they couldn’t walk. We walked down Hosszu Street – today: 1st December Boulevard – in this column. There was a brickyard there that, I think, doesn’t exist anymore.

Several years ago some Israelis or Americans, I don’t know exactly, came here and the Jewish community asked me, among others, to tell them a thing or two about what happened at the brick factory as someone who had been there. But the location had changed so much I could recognize hardly anything.

In 1944 we walked to the ghetto set up in this brickyard. In the first days we consumed everything we had brought from home. Then a so-called kitchen was set up. I think we only had a one-plate meal daily, at noon.

The non-Jewish friends and neighbors left food packages with name tags at the gates of the ghetto, and the guards handed them over to the addressees. We stayed there for three weeks. We were taken directly to Auschwitz with the first transport.

Then a German officer, a commander or some other rank, came and said how many people he needed, so they arranged the requested number of people in rows of five and left the others at the brickyard. I don’t know, but I think they took away everybody in two or three transports.

We were taken to the station on foot, escorted by gendarmes, then they put us on cattle-cars. There were some 70 or 80 people in one car, and there was barely enough room for us. We had no seats or drinking water, as a matter of fact, there was nothing in there.

We used a container as a toilet where everyone who needed, could relieve themselves. The journey took four days. Now and then they opened the doors and gave us some water, but not food. We all had something to eat, but we didn’t know how two apportion it because they told us nothing about where they were taking us.

The cars didn’t even have windows, but there were some small holes we could see through. Someone from the car noticed we had left Hungary, and then everyone despaired because they realized that staying in Hungary was nothing but a lie, and they were taking us further away, God only knew where.

Then, due to the lack of air, some of us became travel-sick. The doors were opened very rarely, only when the train was stopped because there weren’t any free tracks. Everyone tried to guess what would happen next. We comforted each other by saying that at least we were together, and we would pull through it somehow.

We arrived at Auschwitz after four days, early one morning, at the end of May. They opened the doors and everybody had to get off very quickly. Everyone wanted to go for their packs, but they told us those would stay on the train. But all our papers were there, we said, at least they should let us get them.

They said no, we would get them later. We had to get off as we were. Before we got off, we all put on our warm clothes, because it was early morning and quite cold outside.

After everybody got off, they told us men and women had to go separately. We were separated then, but we didn’t know whether we would see each other again, and we had no time to properly say our good-byes.

We had to stand in rows of five, and then came the first selection. The notorious Mengele stood there at the front, with his assistants. [Editor’s note: It is only a presumption that Mengele himself did the selection.] Those with little children on their arms were put aside immediately.

There were women holding other women’s children, but there was no time for explanations. And nobody did, because we had no idea why people were sent to one side or the other.

My mother had a black cashmere shawl with roses, and she put it on her head and across the shoulders to protect herself from the morning cold. Mengele ripped it off her head, but he probably judged her young enough to send her to my group.

We didn’t know then, that this was the ‘life’ side and the other was that of death. They told us that those on the other side – the elderly and the children – would be taken to the showers by car because they couldn’t walk that far.

They were speaking in German, but many of us spoke German. My father, too, spoke almost perfect German. The actual showers, we were taken to, were not that far away. The other ones, which they took the elderly and the children to, those were the gas-chambers. But they too looked like showers, in order that people would think they were. But we only found this out later.

We had to take all our clothes off, and we were left with no clothes of our own. They cut our hair, everywhere, and threw us some of the clothes they had there in piles. It happened that they gave large people small clothes or vice-versa, so we had to exchange our clothes among ourselves. The same happened with the shoes. I was with my mother in Auschwitz.

In the barracks there were three-level bunk-beds. We had to sleep on boards, and there were no blankets or sheets. The space was incredibly narrow, because there was already a large number of people there, and we had to sleep six or seven people in a bunk-bed, packed like sardines in a tin.

If one wanted to turn, all the others had to turn at the same time or there wasn’t enough room to do so. At Auschwitz, since it was an extermination camp, we didn’t have to work. The food was terrible and many of us got sick with diarrhea, which could then be fatal, and others had rashes and died from those.

These camps were fenced off with electrified barbed wire, and those with weaker nerves, who couldn’t take it anymore, decided to grab it and kill themselves. And then there was that idleness...Each day we were woken up early in the morning and rushed to the area between the two blocks.

They aligned us in rows of five and we had to stand there until a German officer came to do the headcount. They already had a record showing how many people were in each block. And there was a block leader who kept telling us not to be ill or get sick – that’s how he tried to convince us to hang on as much as we could –, because he knew how it would end for those who were sick or couldn’t carry on.

We had to wait for hours for the German officer to come and do the headcount. Regardless of the weather we had to stand there even in the rain, getting soaked until the German officer was kind enough to come and take over. This usually took three or four hours.

Then they brought us the so-called breakfast in kettles: some sour coffee or tea, or something like that, made from God knows what. But we had no cups or glasses. They gave us a pot, one for each row of five, and put the drink for five in it.

We couldn’t really split it, so the five agreed to drink first three gulps each, then two gulps, and so on, until it ran out. Then we could go to the wash-room. That was a longer barrack block, and inside it looked like a watering trough, with taps above. But when we were allowed to go in, usually there wasn’t any water, so we turned the tap on in vain.

There were times when we couldn’t wash up because the wash-room was locked. The toilets were pieces of cement you could sit on with holes in the middle. But they weren’t always open, either.

Several hours later, I don’t know exactly when, they brought us lunch. It was awful. I wasn’t too queasy, but I couldn’t even taste it. I couldn’t guess what it was made from: grass or weeds? It had that green color, but that smell...

So my row-mates were lucky because they only had to split it four ways, since I wouldn’t eat it. In the afternoon there was another call, then we had to wait for the headcount again, and another three or four hours passed. Then we had supper. I don’t know exactly, but I think the daily bread ration was 200 or 250 grams.

The bread had the form of an oven pan, cut into five. They gave us a piece of margarine and a slice of salami allegedly made from horse meat, but it didn’t matter because we would have eaten it whatever it was. There were occasions when they put a spoonful of marmalade on the bread, and this was our meal. I lived from this supper because it’s all I used to eat.

In the block I was staying in, there were mostly people from Marosvasarhely and the surroundings: Szovata and Szaszregen. Those who managed to improve their situation by wheedling into the block leader’s favor, or managed to make some friends in the kitchen, could get some additional food.

There were some generous people, who shared it with the others, but some others wouldn’t. But you had to understand that because it was a constant fight for survival, there was no place for charity. We mainly discussed what we would do first when we came home – because everyone hoped we would get away from there eventually.

People said they would take a bath and would stay a whole day in the bath-tub, or they would eat this and that, or they would throw away their wardrobe full of outfits because two are enough and weren’t important, and things like that.

Sometimes German factories sent for people because they needed prisoners to work for free. They used to line us up again in rows, and the delegate selected the people he needed: mostly young, strong and energetic people. My mother and I tried to avoid these selections as much as possible because we didn’t want to be separated.

Often we had to stand there almost naked, so they could see whether people had had any operations – because those who had operation scars or had some physical defects, or something, couldn’t sustain the work as well as the others. My mother had been operated on the year before, and she had a large scar that was quite obvious.

In addition she began to go grey quite early, although she was only 48, and she had even began dyeing her hair at home, before the deportation. We had our hair cut, and as it began to grow back her grey hair began to appear.

The grey hair and the scar, these were good reasons to be sent to the gas chamber, so we tried to hide away from these selections. As soon as we heard one would take place, we hid somewhere, anywhere we could. This went on until October.

In Early October there were very few of us left in the camp, as many had perished or had been taken to work. Those who hadn’t been taken to work had been sent to the gas chambers. We had no opportunity to hide, and by then one could never know when these selections would take place.

On 6th October they opened the doors of the two facing blocks, a cordon of German soldiers was formed and they began to select people and sent them out one by one. Those who had been accepted were sent to the other block, otherwise they were taken elsewhere. That’s how we got separated because I had been found young and strong enough to work.

Those found unfit to work were immediately taken away, of course. Then I knew for sure – they didn’t tell us, but I already knew – that I would be separated from her forever, for she was taken to the gas chamber. Two days later, on 8th October it would have been her 48th birthday.

I was taken to work at a bomb factory, along with two of my former classmates. Empty bombs were brought there, and there the filling for the bombs was boiled. The factory was called Hertine; it was some 90 kilometers from Prague, in the Sudetenland [in today’s Czech Republic].

We found out the nearest town was called Teplice in Czech, but the Germans, of course, who gave a German name to everything, just like they did to Auschwitz, called it Teplitz Schonau. The factory was in a valley, very well camouflaged, and there were some stairs, which lead down to it.

The camp was on top of the hill. This was a smaller camp we lived in. I think there were 600 of us; women and later too – Czech, French and Yugoslav forced laborers. There were only women in our camp; the men didn’t live in our camp, but in a concrete building far away from us.

Compared to Auschwitz, it was heaven because even though we were working in three shifts, we had normal meals and could wash. We slept in smaller wooden barracks with iron bunk-beds, but we all had our own beds with straw mattresses.

It was winter, but it wasn’t cold because we had functioning central heating. We had working clothes made of linen: a pair of trousers and a jacket, and we had to cover our heads. That’s how we dressed for work. After we came out of the factory, we could wear our civilian clothes.

But before that we had to go to the wash-room, which had cold and hot water, and had to shower before we could put on our civilian clothes. There were lockers in the hallway of the barrack block, one between two people, and we had to put our clothes in them. We were treated decently there.

We worked in eight-hour shikhtahs, that is, shifts, there were morning, afternoon and night shikhtahs. [Shikhtah means shift in Hebrew.] I had to work a week in the morning shift, then another week in the afternoon shift, followed by a week in the night shift.

At the middle of the working day, that is, after four hours, we had a quarter or a half an hour lunch break. Also within the factory there was a hall they called the canteen. The German guards escorted us there, and there everyone was given a sandwich. I was very lucky because I wasn’t working in the most dangerous zone, where the poison was boiled.

I was assigned to work where the empty bombs came in. The same number had to be written on the body and on the tail of the bomb, then this tail, which was screwed on to the body, had to be removed from it.

I worked on the empty ones, but the process reached a point where they had to be filled. Many of those who worked there got sick. They got a bottle of milk – a quarter or a half a liter, I don’t know exactly.

We, who weren’t working in the dangerous zone, were given only a sandwich: two thin slices of bread spread with margarine, with salami between them, packaged in white paper. I tell you this was a heavenly place, and there were only a few of these [under the given circumstances], so from this point of view I was lucky.

Men were working there, also, and they managed to sabotage the factory by causing an explosion. This happened during nighttime, when I was working on the night shikhtah, but it caught me right when I was on my lunch break.

They timed it this way, so none of the workers were hurt. We were just eating our lunch at the canteen, when this explosion happened. The Germans had quite a scare and they had to close down the factory because there was too much damage to be repaired quickly. Then they took us to do agricultural work, because it was already spring, April.

By then the front was very close. One day they packed us up, put us on a train and took us to the Czech town of Litomerice, Leitmeritz in German. There we got off the train and set off on foot, but we didn’t even know where to. The German soldiers came along. After a while we arrived at something like a gate, and they told us to go inside.

The German soldiers remained outside, and that was really odd. This was the famous Terezin, Theresienstadt 13 in German, from which I was later liberated. During the war, this place was something like a shop-window, which the Germans showed to the outside world and the Red Cross, when the news about the deportations spread.

They showed them it was true that they gathered the Jews in one place, but the families, including the elderly and children, were all together. At first it was all true, but after they showed it to the Red Cross they deported people even from there.

By the time we arrived there we saw no children or elderly people, but anyway, they helped us to take refuge there, and there were no German guards left there. This happened in late April, and we had to wait for another week or ten days until the war was finally over and, on 8th or 9th May, I always forget, I was liberated. One could somehow feel then the war would actually be over. I was liberated by the Russians.

- Post-war

It took us quite a long time to get home because we couldn’t find a train there, and even if there were carriages, there were no locomotives. Eventually, after some two weeks, we got one and came home on it. I was with one of my former classmates, Vera Kertesz.

The other one, Lili Abraham, got sick with typhus, but fortunately she recovered, so she came home not long after us. They had been left by themselves already in May, when we arrived in Auschwitz, because they had been separated from their mothers.

So we stayed together, especially after I was left alone, too, and from then on we became even better friends. I don’t remember exactly the route by which we came home after the liberation because of the many stops we had in open fields. I only remember Budapest.

We got off there because one of my girlfriends had an uncle living there. They escaped the deportation because there were protected houses in Budapest from which the Jews weren’t deported after a while, and somehow they managed to escape.

We stayed there for about two days before we set off for home by train. We had a long stop at the border near Nagyvarad because some documents had to be filled out about the place we were coming from. There we had to go to the Jewish hospital to be disinfected, and only after they gave us documents stating that we were clean and healthy, did they allow us to carry on.

I knew it was useless to wait for my parents, but I was hoping my brother would come home, after all, he was young. The girlfriend I came home with was lucky because her older brother, Gyuri Kertesz, who was the same age as my brother, was waiting for her at the station.

Everyone who had someone to wait for was at the station. I was hopeful until one of his comrades came home. When he arrived he told me there was no one for me to wait for unfortunately. He found, in a rubbish bin, one of our family pictures, taken when my brother came home in March 1944, and the man had it on him all the time. He gave me that photo and I put it in the family album. So that picture survived a war.

When I arrived home, the house already had many inhabitants, and different families lived in each room. It was very hard to find a home then. The Zsido Demokrata Szovetseg [Jewish Democratic Union] organized the reception very well:

a sanatorium was set up on the corner of Koteles Samuel Street, and everyone who came home and had no place to stay, could go there. I think people were allowed to stay there for two weeks. A meal was given away for free, arranged by the Union.

There were, of course, these American Jewish world organizations, which financed them so they could arrange it, because the people from the Union were also people who had just come home and thus they had no money.

I ended up in the sanatorium because our house was full. There was the attic room in our house, three rooms below, and in the back there was the large kitchen people also used as a bedroom. Those who lived in the attic and the room below it emptied the room for me and moved to the attic.

The original furniture wasn’t there anymore, only what I could get: a painted cupboard, an oak dressing-table that initially belonged to my family; it was incomplete already, though, but I could move in.

When my girlfriend Lili, who had become ill, came home later, she too, was all by herself, and we moved into our house because this sanatorium only operated for a short while. We lived in the same room and we had a common bathroom since the house only had one.

We had to cross the other rooms to get to the bathroom. At that time the Joint 14 helped the local organization to set up a girls’ home and a boys’ home in two houses that belonged to Jews who never came back. The girl’s home was on Koteles Samuel Street, almost facing the University of Dramatic Art.

The boys’ home was somewhere around the main station, but I don’t know exactly in which house. For those who came back alone and had nowhere to go houses with three, four or more rooms had been set up, with five or six beds in each of the rooms, because those were large rooms.

These people even got free meals. Although we had somewhere to live, my girlfriend and I went to the girls’ home to eat; they cooked there. An older lady who came back from the deportation took on the job of cooking for a certain number of people.

Most of the ingredients were sent by the Joint, so they had no problem with the supplies, and she only had to organize things. The Joint sent different packages with clothes collected by the Jewish organizations there, and these clothes were distributed amongst the home-comers.

We ate for a while at the home, but there was a small canteen nearby, ran by a lady I knew, and she offered to give me meals, and I didn’t have to pay too much for them, so from then on I went there to eat.

We had to find ourselves jobs because we had no money at all. Each home-comer got a certain sum of money, just to ensure they weren’t left without any, but it was a small amount. Jewish stores began to appear by then. There were wealthy people who had stores even before the war, and after they came back they carried on with their businesses.

I was employed in such a store as a cashier. The owner was a Jew called Leb. He wasn’t originally from Marosvasarhely, but from a nearby village, and he left the city shortly afterwards. Another store was opened in the vicinity by a lady older than me.

She came back from the deportation, too. She did some administrative activities, and hired me to do some book-keeping, and this and that. She showed me and taught me what to do, and thus I restarted my life. I worked for her from 1946 until 1948.

In 1948 these private businesses were nationalized [during the nationalization in Romania] 15 and it became a public store. A man from Brasso courted her, she married him and she moved away.

My girlfriend Lili, though, got herself a job at a bank with Jewish interests called Kishitel Bank [Small Credit Bank]. Another thing was that when I was deported, I’d just finished 7th grade, which would now be 11th.

Those who came back could attend 8th grade unofficially, just to allow them to finish school. Thus my girlfriend and I managed to finish 8th grade, but we just finished this one because we had to work and we didn’t have much time for studying.

But we didn’t graduate because there wasn’t such an exam board here in Marosvasarhely, and we would have had to go to Brasso or Kolozsvar or somewhere else to graduate. But we had no money because the small amount we’d been given was already gone.

The salary was so small, too, and we had to sustain ourselves. I didn’t have to pay rent, that much is true, but I had to pay the house tax, because the house was still registered under my parents’ name, although there were others living in it.

I didn’t want to emigrate because I was too immature. Nowadays 15-year-old children are much more informed, and even though I was 18 when I returned, I think I had the mind of a 12-year-old in today’s terms. I had no idea how this emigration thing worked.

I thought if I ended up in a foreign country, I wouldn’t know anybody. I didn’t really have the courage to do it. With my current view and mind I would have probably done everything differently. Back then people, including myself, were happy that they were alive and had made it through the war.

We couldn’t do anything to bring our parents back, but we hoped everything would turn out right from now on. They kept telling us how perfect socialism would be. Indeed, people were all alike, nobody asked whether you were Romanian, Hungarian, Jewish, Saxon or Hottentot, it didn’t matter, really.

There was real brotherhood because everyone was happy and gave a sigh of relief after the misery of the war ended. People were somewhat nicer then, they were ready to help, and they weren’t as wicked as they are now. We started to work, so full of enthusiasm, it didn’t matter if we worked overtime.

We were happy to have a job and keen to work well. In those days, Saturday was a working day. Moreover, there were culture brigades who even on Sundays went from village to village and everyone who had a nice voice or could recite was taken to shows because everyone had to get involved in everything.

In November 1948 I got a job at a state company called ICS, the abbreviation of something like Intreprindere Comerciala de Stat in Mures [Commercial State Company in Mures]. I retired from there in January 1982. This company was large, it included all the textile, iron and wood warehouses, but not food warehouses.

The restaurants, canteens and pubs pertained to another company. The offices of ICS were on the corner of Bolyai Street and the main square [in the building of the current Korzo], where a big hotel will now be built, that’s where I used to go up and down the stairs. The offices were on the 1st floor of this two-storied building. I used to work in the office, and all the stores pertained to it.

In the first year we had these endless meetings at work. Each morning, before we began working, there was half an hour of newspaper reading, but I don’t recall the title of the newspaper because I didn’t subscribe to any of them.

The accounting department had a department chief who used to read out the articles, and then we could comment, ask questions or discuss issues. They read political stuff, of course, and praised socialism.

There were things I believed, but then again, things I didn’t. There was still an atmosphere of apathy and people believed that maybe something good would happen. Back then, the companies organized balls one after the other, for all kinds of occasions.