Bluma Katz

Mogilyov-Podolskiy

Ukraine

Date of interview: July 2004

Interviewer: Ella Levitskaya

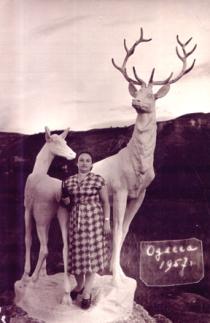

Bluma Katz and her husband live in a one-bedroom apartment of a house built in the 1970s. Bluma is short and fat. She has signs of gray in her wavy hair cut short. She looks young for her age. She hardly ever goes out having to look after her severely ill husband and is very happy to have guests. She speaks with a slight Jewish accent. She willingly tells me about her family and her life. Bluma is a diligent housewife. Though they have a visiting nurse from the Jewish community helping her about the house, Bluma prefers to do as much as she can herself. She keeps her apartment clean and cozy. There are books on the shelves. They are mainly Russian classical books and Russian translations of Jewish authors. There are many agricultural books – it is Bluma’s profession. She worked at the agricultural machine building plant and is a well-respected person in Mogilyov-Podolskiy.

My mother and father came from Ozarintsy town in Vinnitsa region [about 300 km from Kiev], which was Vinnitsa province at the time. Ozarintsy was one of many Jewish towns in Vinnitsa region that was within the pale of Settlement 1 in Russia.

The Jewish part of Ozarintsy consisted of about 200 houses. Ozarintsy was located in the beautiful area: there were woods, ravines and a river with clear water. There was a stream in the woods where water was ice-cold even in hot weather.

Here was a Jewish hospital and a pharmacy, a Jewish school and a cheder in Ozarintsy before the revolution 1917 2. There was a 2-stiried synagogue and a shochet in the town. There was a Jewish cemetery in the suburb of the town. Many Jews dealt in farming and kept livestock: cows, goats and sheep. There were vast fields surrounding the town. Everybody could rent at the owner of the ground, a rich Ukrainian merchant, as much lad as they could manage. They grew sheep for meat and wool. They made brynza – delicious sheep cheese getting ripe in marinade. There was a cheese making shop before and after the revolution of 1917 selling in at the markets in Vinnitsa and Khmelnitskiy.

Most of the houses were made of stone. There were solid stone porches. People got together to build houses. After the day’s work they sat to dinner together. Ozarintsy was one big family. They celebrated weddings together and lived a common lie for small towns where all people knew each other. Jews spoke Yiddish to one another, but they also got along well with Ukrainians. They had Ukrainian friends. Many generations of Ukrainian and Jewish families lived side by side in the course of time. Ukrainians understood Yiddish and had no communication problems with Jews. Before the revolution and during the Civil War 3 there were Jewish pogroms in Ozarintsy made by gangs 5, or Denikin 6 troops. Local Ukrainians often gave shelter to Jewish families risking their lives.

All Jews in Ozarintsy were religious. Despite the struggle of Soviet authorities against religion 7 the synagogue in Ozarintsy was not closed until the middle 1950s. Jews celebrated Sabbath an Jewish holidays and observed Jewish traditions. Boys had brit milah and bar mitzvah after they turned 13. Of course, the time had its impact on the Jewish way of life. The generation of my grandmother wore wigs and kerchiefs and long dark clothes. Men had beards and wore hats or caps, but the following generations wore casual clothes, did not cover their heads, women did not cut their hair before the chuppah. On Jewish holidays all Jews went to the synagogue anyway. Many men went to the synagogue before work on weekdays.

There was a big market in the center of the village where Jewish and Ukrainian farmers sold their products. All Jews followed kashrut. Housewives bought living poultry to take it to the shochet. There was a butcher’s store selling kosher meat. Farmers delivered dairy products to Jewish homes. All food was delicious.

My paternal grandfather’s name was Endl Katz. I don’t remember my grandmother’s name: we called her ‘granny’. I think they were born in the 1850s. My grandfather was a shochet. After the revolution he kept sheep. My grandmother was a housewife. My grandfather was short, thin and had a gray beard. On weekdays my grandfather wore his work robes. On Sabbath and before going to the synagogue he put on his long black kitel. At home grandfather wore a black silk yarmulke, and he put on his cap or black hat to go out. My grandmother was short and plump. She was duck-legged, but she moved around quickly. My grandmother wore a black kerchief, long skirts with gathers and long-sleeved and closed-neck blouses.

There were five children in the family. My father’s oldest brother moved to USA before the revolution and there were no contacts with him. The rest of my grandparents’ children lived in Ozarintsy. I don’t remember their dates of birth. The oldest was my father’s brother Mehl, then came Moishe and my father Benumin, and their younger sister Bluma. Bluma died in the year when I was born. My father and his brothers went to the cheder. My father could read and write in Hebrew and Yiddish and knew prayers. They also finished the 7-year Jewish school. My father’s brothers helped their father with taking care of the sheep. After the revolution of 1917 my father went to study at the rabfak 8. After finishing it he went to work as an accountant in the Jewish kolkhoz 9 in Ozarintsy. My father’s older brothers went to work in the sheep farm in the kolkhoz. They both had Jewish wives, whose names I don’t remember. Mehl had three sons and Moishe had two sons and a daughter. I don’t remember their names.

My maternal grandfather’s name was David Gass. My grandmother Bluma Gass died in 1919 and I did not know her. My grandfather was a tailor. My mother told me that grandmother had 9 babies, but only four survived. My mother’s older brother Gershl moved to USA during the civil War and I have no information about him. Her second son Borukh was born in 1898. In 1900 my mother Golda was born and one year later – her sister Haya. Borukh studied in the cheder. My mother and her sister had a visiting teacher, who taught them Jewish traditions and Hebrew alphabet to be able to read prayers. They were not taught to understand them since only boys were taught to translate from Hebrew. The family was religious. They celebrated Sabbath and Jewish holidays and followed kashrut. They observed all traditions.

The children finished a primary Jewish school and went to study in the 7-year Ukrainian school. After finishing school Borukh went to work for the forester and later became a forester himself. His wife Riva came from Ozarintsy. They had two children. My mother and her younger sister Haya became apprentices of a seamstress. They worked as seamstresses before getting married. They made bed sheets, night gowns and women’s underwear. Haya had a prearranged wedding. She married a Jewish guy from Luchentsy village of Vinnitsa region. They had a traditional Jewish wedding in the bride’s home. After the wedding Haya moved to live with her husband. She was a housewife and had three daughters: Betia, Mania and Golda.

I don’t know how my parents met. Since they both came from Ozarintsy where their families lived in the same street and my parents must have known each other. My parents got married in 1921. They had a traditional Jewish wedding. Mama said that there were tables installed along the street and the whole village celebrated their wedding. My parents lived with my father’s parents. My grandfather had a big house consisting of two parts. There were few fruit trees and a small vegetable garden in the backyard. There was a porch and fore room with three doors in it: one to the living room and two doors on each side to the different parts of the house. Each part had two rooms and kitchen. There were wood stoked stoves in the kitchens. The stoves heated the rooms. Housewives in Ozarintsy baked bread for their families, though there was a bakery in the village. My parents lived in one part of the house. My father worked as an accountant in the kolkhoz. My mother was a housewife. My parents observed Jewish traditions, but their appearances were no different from those of Ukrainians. Men didn’t have beards or cover their heads. Mama only wore a kerchief to go to the synagogue or on Sabbath and Jewish holidays.

Mama gave birth to three children. She didn’t go to hospital, when the babies were due. She had an assistant doctor and a midwife assisting her delivery. I was the first child. I was born in 1922 and was named Bluma after my mother’s mother and my father’s deceased sister. In 1928 my sister was born. She was given the Russian name of Lubov, Jewish Liebe. In 1930 our brother Boris, Jewish Borukh, was born. He was circumcised according to Jewish traditions.

Our parents spoke Yiddish to us. Of course, we also spoke Ukrainian. My parents celebrated Sabbath and Jewish holidays and were religious like all other Jewish families in Ozarintsy. Before Pesach all Jews whitewashed their houses and fences. About a month before the holiday they started making matzah. Several Jewish housewives got together on one house to make matzah for this family. Each of them had her own responsibility: one made the dough, another one rolled it and the others did the baking. Next day they went to another house. There was no bread in Jewish houses during Pesach. All housewives had their own recipes for traditional food. There was plenty of it cooked for the holiday. Mama made read borsch, chicken broth, puddings, stuffed fish, and chicken neck with liver and fried onions. She also made strudels, honey cakes and star-shaped cookies from matzah flour crushed in a mortar and sieved. Mama followed the kashrut. She had separate dishes for meat and dairy products. Every Jewish family had special crockery and utensils for Pesach that was kept in attics for the rest of the year. On the first day of Pesach my parents went to the synagogue. My parents took me with them, but left the younger ones in a Ukrainian farmer’s care. On our way back home mama went to this Ukrainian woman to pick my younger sister and brother. We, children, did not know Hebrew. Mama and papa read prayers in Hebrew and translated them into Yiddish for us. During seder each person had to drink four glasses of wine. Children sipped wine from little glasses. Then we all sang jolly songs. I don’t remember anything about Rosh Hashanah, but I remember Yom Kippur that followed the Rosh Hashanah. The family had a substantial dinner before the first star appeared in the sky. Then the fast began, which lasted till evening of the following day. On Yom Kippur all Jewish families conducted the Kapores ritual. Farmers sold white chickens before Yom Kippur. They knew that nobody would buy black or speckled chickens from them before Yom Kippur. Housewives bought white hens for girls and women and white rosters for men and boys. The chickens had their legs tied. One had to recite a prayer, take the chicken and turn it over one’s head pronouncing: ‘May you be my atonement’. Parents turned the chickens over their children’s heads. I don’t know what happened to this chicken afterward. My parents strictly followed the fast, but mama always cooked for the children to have food while they were at the synagogue. The children usually missed one meal to give tribute to the tradition. I remember asking mama to let me fast a whole day like all adults did, but mama didn’t allow me to do it. My parents went to the synagogue in the morning and spent a whole day praying. Younger children came to the synagogue for a short time. My younger sister also came to us at the synagogue for one or two hours. After Yom Kippur the Sukkot was celebrated. All Jewish families had a sukkah installed in the yard and decorated it with branches and flowers. There was a table installed in the sukkah where the family had meals and prayed. We also celebrated Chanukkah and Purim. All I remember is that on Chanukkah we had a chanukkiyah on the table and mama lit one candle every day.

We also celebrated Sabbath. We had two bronze candle stands where mama lit candles on Friday evening. She covered her face with her hands and prayed over the candles. Occasionally we celebrated Sabbath with grandmother and grandfather. Saturday was a day off since it was the Jewish kolkhoz that made Saturday a day off in Ozarintsy while the rest of the USSR had an official day off on Sunday. When they returned home, my father sat down to read religious books to us. He translated what he read into Yiddish for us. Mama had dinner ready, which she cooked the day before and left it in the oven to keep it warm. Adults were not to turn on the lights or stoke the stove on Saturday, while the children were allowed to do little chores. On Saturday we often visited uncle Borukh, my mother’s brother. His wife Riva made barley flour pancakes on Sabbath. We liked them a lot. The adults talked and we played with Borukh’s children.

I went to the 7-year Jewish school in Ozarintsy where we studied in Yiddish. I had excellent marks in all subjects at school. I studied 3 years in Ozarintsy. In autumn 1931 my father was offered a job of director of the MTS [equipment maintenance yard – they repaired plant and equipment for kolkhozes in Vinnitsa region] canteen in Vendichany village near Ozarintsy. They promised him a higher salary and lodging. My parents decided to move there. Jews constituted maximum 30% of the total population in Vendichany. There was a sugar factory in the village.

My father received a house for the family to lodge in it. It was a big stone house with a brick plastered fence around it. The house had three rooms and a kitchen. There was a stove in the kitchen. It also heated my parents’ bedroom. There were stoves in other rooms as well. My sister, my brother and I slept in one room, and the third room was a living room. There was a wood shed in the yard and apple trees near the house. There was also a well near the house.

Many women in Vendichany went to work. Mama began to make bed sheets at home. Her clients paid her with food products or money. We were rather wealthy at the time. In 1932 famine 10 occurred in Ukraine. Our family did not suffer from hunger, as after as I can remember. My father and his employees received rationed food and so did employees of the equipment yard. Also, residents of Vendichany could buy food products in Mogilyov-Podolskiy. The situation with food supplies was better in towns. At least, there were no victims of hunger in Vendichany.

One Jewish resident of Vendichany had a 2-storied house. Two rooms on the first floor served as a prayer house in Vendichany. There was a small window in the wall between the rooms for women to listen to the rabbi’s service. Men went to the prayer house on Sabbath and on holidays and women – only on holidays. Men wore kippahs or hats and women wore kerchiefs or beautiful silk scarves to go to the prayer house. All Jews celebrated Sabbath and Jewish holidays, but some younger people observed Jewish traditions no longer. We celebrated Sabbath and Jewish holidays like we did when living in Ozarintsy. My father brought matzah for Pesach from Mogilyov-Podolskiy. My parents fasted on Yom Kippur. We could not celebrate Sabbath following all rules, but mama lit candles on Friday evening, we prayed and had dinner. My father had to go to work on Saturday since the equipment yard was open and its employees needed to have meals. Mama didn’t sew on Saturday. There was no anti-Semitism in the village. We got along well with Ukrainians,. I remember that on Easter our Ukrainian neighbor brought us Easter bread and painted eggs and mama gave her family matzah on Pesach. People respected each other’s religion and traditions.

We spoke Yiddish at home as we were used to, and Ukrainian to our Ukrainian neighbors. I went to the 7-year Ukrainian school in Vendichany. My sister also went to this school later. There were quite a few Jewish students at school. There was no anti-Semitism – perhaps it did not exist before the war. I had Jewish and Ukrainian friends. We were taught to be internationalists at school. Nationality didn’t matter to me. We were told that we had one nationality – we were Soviet people. I became a pioneer 11, and was very proud wearing my red neck tie. After finishing school my parents began to think about my further studies. They wanted me to enter a college which required a full secondary education. There was no place to continue education in Vendichany while there were higher secondary schools in Mogilyov-Podolskiy. My father went to Mogilyov-Podolskiy, found a job and our family moved to Mogilyov-Podolskiy.

My parents bought a small shabby house in the center of the town. During the German occupation this house happened to be within the boundaries of the ghetto. This was mainly a Jewish district. Mogilyov-Podolskiy was a Jewish town where over half of its population was Jewish. There were few synagogues, shochets and a Jewish school in the town. This was a lovely southern town buried in verdure. Jews resided in the central part of the town. They engaged in crafts and were tailors, shoemakers and barbers. Any Jews worked at supply agencies and owned stores. Mogilyov-Podolskiy stands on the Dnestr River. It lies between the Dnestr River on one side and the limestone hills covered with woods – on the other. There were cemeteries on the hills: a Jewish, a Catholic and a town cemetery. Bessarabia 12 lay on the opposite bank of the river. In 1940 this area was annexed to the USSR: Romania gave up to few ultimatums of the USSR, but before this happened Mogilyov-Podolskiy was a frontier town. Its streets were patrolled and there were special permits required to come into the town. Jews mostly resided in the central part of the town. Their houses closely adjusted to one another. There were small backyards where only a little shed or a tiny vegetable garden could fit while in the suburbs residents had orchards, vegetable gardens and fields. They sold food products in the town. There was a loyal attitude to Jews in Mogilyov-Podolskiy. There was also Russian, Ukrainian, Moldavian and Greek population in the town. There were churches of all confessions, many of which were closed during the period of struggle against religion.

We lived in a house made from air bricks – a mixture of cut straw and clay bricks dried in the sun - like most other houses in Mogilyov-Podolskiy. There were few stone houses owned by wealthier people. We certainly lived in better houses in Ozarintsy and Vendichany than the one we had in Mogilyov-Podolskiy. However, my parents believed it was more important for their children to get education than concentrate on certain discomforts. I went to the 8th form of a Russian school and my brother and sister later also went to this school. At first it was difficult for me to speak Russian. Many Ukrainian words slipped off my tongue. However, my Russian gradually improved. I studied well. I liked school and only had good and excellent marks for my studies. In the 8th form I joined the Komsomol 13. I studied a lot to get ready for the interview at the town Komsomol committee. We were to answer questions related to biographies of party and state leaders, political situation in the country and in the world, the history of Komsomol and the communist party of the USSR. I was excited, but I answered all questions well and obtained a Komsomol membership card and a badge.

This was the period of persecution of ‘enemies of the people’ 14, arrests in 1937 and the following years 15. We had to remove our textbook pages with portraits of the state and party leaders that happened to be ‘enemies of the people’ and cross out their names. Like many other people I believed that those people were guilty. We were raised to have no doubts in the infallibility of the party and Stalin. When newspapers wrote about denunciation of another enemy of the people, how could I have doubts … Nobody in our family suffered during the period of arrests. I remember that one of my father’s acquaintances or colleagues and my parents discussed this in the evening.

In 1930 my mother’s father David Gass died. He was buried by the grandmother’s grave in the Jewish cemetery in Ozarintsy. The funeral was Jewish. Our parents went to the funeral to Ozarintsy, but left the children at home. In the middle 1930s my father’s father Edl Katz died. My grandmother died one year afterward. They were buried near the gate to the Jewish cemetery in Ozarintsy.

I finished school in 1940. I wanted to study foreign languages and become a translator. My mother’s distant relative Yekaterina Spiegelman, who lived in Kharkov had graduated from the Philological Faculty of Kharkov University and worked in a publishing house. Her husband Vitaliy Cherviakov was Russian. He lectured at Kharkov University. My father went to Kharkov with me. I passed exams and entered the Faculty of Translators of College of Foreign languages. There was no problem for Jews to enter higher educational institutions at that time. Admission was based on the marks and origin Children of workers and peasants had more chances than children of non-manual workers. I studied German and English. My father went back home and I stayed with Yekaterina and Vitaliy. They were atheists and living in their home I did not observe Jewish traditions.

When I moved to Kharkov my parents and my younger brother and sister returned to Ozarintsy. My father’s brothers Mehl and Moishe and my mother’s brother Borukh lived in Ozarintsy and my parents wanted to be closer to them. They moved into my father parents’ house. My sister and brother studied in the 7-year Ukrainian school in Ozarintsy. My father resumed his work as an accountant in the Jewish kolkhoz.

I finished the first year in College. On 21 June 1941 I passed my last exam and the next morning I was to join my family in Ozarintsy. I had sent my parents a cable and was planning to do some shopping to buy presents on Sunday. On the morning of 22 June 1941 16 I woke up early in the morning and started packing. Yekaterina and her husband were not at home. I was about to leave, when Yekaterina ran into the apartment and turned on the radio. She had a scared expression in her eyes. The radio announced that the Hitler’s Germany attacked the USSR without announcement of the war violating the peace treaty. We froze with fear. Then Stalin spoke and I can still remember his words: ‘Our army will defeat the enemy, we will win the victory’. Somehow this calmed me down instantly. We had been convinced that if somebody attacked the USSR, it would be a ‘blitzkrieg’ war and our army would beat the enemy on its territory. We sang songs: ‘If tomorrow is the war, if tomorrow we have to go to the war, if a dark force shall attack, our Soviet people will stand like one for our beloved Motherland…’, we watched movies where it took our army a week to beat the enemy’. We had no doubts about our victory. We were so sure about it that when evacuation of Kharkov began, we didn’t consider evacuation. I was convinced that only coward and those who did not believe in the strength of our army were running away. If Stalin said that we would win then it would be so. We listened to news from the front line and were concerned about our army retreating and incurring huge losses. Later there appeared rumors that fascists were exterminating Jews and taking them to ghettos. Yekaterina decided that we should leave Kharkov. We took the last train leaving Kharkov. The trip was fearful. Germans were close to Kharkov. German planes often attacked the train.

We arrived at Timashevo village of Kuibyshev region and were accommodated in a local house. Al local residents sympathized with evacuated people and tried to help as much as they could. A metallurgical plant from the central part of Russia evacuated to Timashevo. Yekaterina, her husband and I went to work at the construction of this plant. I worked winch. In spring 1942 the plant started operation and I went to work at the shop manufacturing heads for cannon shells. We delivered rough blocks for cannon shell heads on carts and I removed wire edges from them with a file. We received workers’ cards 17, for bread. Of course, we had little food, but we could manage on it. I didn’t have information about my family till the very end of the war. I took an effort to find them through the evacuation search bureau in Buguruslan hoping that they managed to escape from Ozarintsy, but I got the same reply: ‘Not found in evacuation lists’. I listened to news on the radio. Our army kept retreating incurring big losses. Germans were advancing to Moscow and this was scary. I already understand about the war. I knew the war was different from Soviet movies and that it was going to take a while before it ended. There was a Komsomol committee at the plant. When we heard about admission to a course of radio operators, many employees applied to the course. I was one of them. There were over 100 attendants at the course. We had classes after work in the evening. We were trained to work with a telegraph unit. After finishing this course we were sent to military units near Oryol in Russia. We were to be radio operators. I became a telegraph operator at the regiment headquarters. We were accommodated in barracks and received military uniforms. We were privates. I stayed there for two months before the commandment issued an order releasing those who had studied in colleges before the war.

Almost all agricultural workers were recruited to the army. There was a demand in new personnel. An Agricultural College opened at Kinel station near Timashevo. All former students were sent to study there regardless where they had studied before the war. There were no entrance exams. All we had to submit was a request. I became a student of the Faculty of selection and seed farming specializing in phytopathology, plant diseases. We were accommodated in a former school adjusted to make a dormitory. I didn’t have any clothes, but the uniform fufaika jacket, skirt and boots that I received in the army. Nobody cared about such things them. We received bread cards and had one meal per day at the college canteen. I shared my room with 5 other girls from various places of various nationalities. We shared everything we had: clothes, food and books. In the evening we talked about our prewar life, made plans for the future peaceful life.

In March 1943 I heard on the radio that the Soviet army liberated Vinnitsa region from fascists. I wrote to Ozarintsy and mama’s sister from Luchentsy. There was no reply from them, but I received a letter from our Ukrainian neighbor. She wrote about the ghetto in Ozarintsy and that all inmates of the ghetto were killed in late August 1942. She did not say a word about my family, but I understood that my mother, father, sister and brother shared the fate of the other inmates of the ghetto. This was horrific news. I lost my hope to see my family again: I was alone in this world. I did not care any longer: I didn’t eat, didn’t attend classes, read or talk to friends. I stayed in bed crying. My friends helped me to recover and I began to attend classes.

On 9 May 1945 the war was over. This was a happy day. People greeted each other and shared the joy that the war was over. There was grief about those who never lived to see this day. I thought about my dear ones. There was no place for me to go. Yekaterina and her husband went back to Kharkov. I decided to stay in college in Kinel. In June 1945 I passed my summer exams successfully and became a 4th-year student. I also finished the 4th year in Kinel and then the college moved to Kharkov. I studied my last year in Kharkov. I lived in the dormitory. Yekaterina and her husband supported me and gave me money. I corresponded with my school friend from Mogilyov-Podolskiy. She wrote me once that my mother, sister and brother were in the town. She gave me their address and I wrote them, though I could not believe they were alive. The day, when I got their response was the happiest day in my life. I couldn’t wait till I passed my graduate exams and could go to my family. After finishing the college I went to Mogilyov-Podolskiy. My family knew that I was arriving and were waiting for me. This was a happy family reunion. We kept talking – we hadn’t seen each other for so long. They told me that German troops occupied Ozarintsy on the first days of the war, fenced the Jewish district and made a ghetto of it. Later Germans left leaving the ghetto in the command of Romanian troops. Endless numbers of Jews from Moldova and Bessarabia began to arrive at the ghetto. They were accommodated in local houses. There were 6 other families besides my parents in the house of my father’s parents. Moldovan Jews could only speak Yiddish. Inmates of the ghetto were not provided any food and had to find it themselves. Risking their lives they left the ghetto earn or buy some food for their families. Mama and my younger brother Boris went to Vendichany to buy sugar that they were selling in glasses in the ghetto to earn some money to buy corn flour, potatoes and salt. Once German guards chased after them. Mama and my brother managed to hide away and the Germans passed by without discovering them. In spring 1942 the ghetto was struck by a horrible epidemic of typhus. All members of my family had it, but they survived, fortunately. After having the typhus Boris fell ill with the Botkin’s disease. He was taken to the village hospital. He recovered, but he had liver problems for the rest of his life. My father older brother Moishe’s wife and daughter and my mother brother Borukh’s wife died from typhus.

In summer 1942 Germans lined up all men over 15 years of age, took them to the field where they had a pt dug out and shot them all. Many of them were wounded, but they buried them alive. Ukrainian villagers said the earth stirred for a while, as f people were trying to get out of there. My mother’s brother Borukh, the forester and my father’s older Moishe Katz perished in this hooting. My father survived. He was wounded in his chest. When the Romanian and German guards moved farther away along the line shooting at the people he crawled away to the nearby corn field. When everything was over few people from Ozarintsy came to the shooting spot looking for survivors. My father called them and they took them back home in the ghetto. My father was bleeding and needed medical assistance. Those same people brought a doctor from the village, but he could not help my father: the bullet stuck too close to his heart. My father bled to death in his presence. The Romanian guards of the ghetto allowed to bury my father in the Jewish cemetery in Ozarintsy, but no Jewish ritual was allowed. We installed the gravestones on my father’s grave and on his parents’ graves after the war. Every year on the anniversary of his death we came to his grave. My brother recited Kaddish for my father, grandmother and grandfather. There were more mass shootings afterward: there were raids in the ghetto – the captives were taken to the suburb of the village and killed. In March 1943 the Soviet army liberated Ozarintsy. Many Ukrainians were helping Jews in the ghetto even risking their lives. There are many Righteous men in Ozarintsy. Many people owe their lives to them. There are no more Jews left in Ozarintsy, though. The survivors could stay in the place associated with such terrible memories no longer, but we all come to Ozarintsy on the anniversary of the mass shooting to go to the cemetery. The rabbi recites a prayer and relatives of the deceased recite the Kaddish after their dear ones.

Mama stayed in the village with the children for some time. In spring 1945 they moved to Mogilyov-Podolskiy. My sister and brother finished the 10-year Ukrainian general education school in Mogilyov-Podolskiy. My sister went to work as a secretary in the music school. Lubov met her future husband Ilia Lozover in Ozarintsy. His family lived nearby. Ilia is few years older than my sister. He turned 18 at the beginning of the war and was regimented to the army. He was severely wounded and demobilized as an invalid of the war in autumn 1944. He returned home and entered the extramural accounting department of Vinnitsa Financial and Economic College. Ilia and my sister got married in Mogilyov-Podolskiy in 1947. They had a traditional Jewish wedding with a chuppah. The rabbi from the synagogue of Mogilyov-Podolskiy conducted the wedding ceremony. Ilia went to work as chief accountant of Mogilyov-Podolskiy district consumer society. In 1948 their son Boris and in 1960 their daughter Svetlana were born.

My brother Boris finished school with all excellent marks and entered Kiev Financial and Economic College. He lived in the dormitory and spent vacations in Mogilyov-Podolskiy. Boris finished the college with honors and could choose a location for his job assignment. He decided for Mogilyov-Podolskiy. He was offered a job of an accountant at the agricultural machine building plant named after Kirov. Soon he was promoted to chief accountant of the plant. My brother was a convinced communist and joined the party at the plant. He married Regina Samoilova, a Jewish girl from Vinnitsa, in the late 1950s. He met her in Kiev. Regina studied in Kiev Medical College. She followed her husband to Mogilyov-Podolskiy, where she was a cardiologist in the local hospital. They had a secular wedding. Their son Viacheslav was born in 1963. My brother died young, when he was a little over 40. His liver problems that he had after the Botkin disease that he had in the ghetto resulted in the cirrhosis. The plant management arranged for my brother to go to the best clinic in Moscow, but there was nothing the doctors could do to help my brother. Boris died in 1974. The cemetery is on a hill in Mogilyov-Podolskiy and workers of the plant carried my brother’s casket on their shoulders taking turns the whole way up the hill. Everybody loved him. The funeral was secular. Regina never remarried. She moved to Perm town in Russia where she had relatives. She worked and raised her son. Viacheslav finished the Faculty of Economy and Law of Perm University. He works as senior credit inspector in a bank. Regina is chief of the cardiology department of the hospital for invalids of the war.

My mother observed Jewish traditions after the war. My sister, y brother or I did not observe traditions at our homes, but we celebrated Jewish holidays with mama and occasionally got together to celebrate Sabbath on Friday evening.

When I returned to Mogilyov-Podolskiy I went to teach at the agricultural courses. I worked there for a year. I got along well with my colleagues and students. I faced no anti-Semitism. I got married in 1949. Our neighbor had a relative in Chernovtsy, regional town of Bukovina [650 km from Kiev] who was single. She told me about him. When he visited her, she introduced him to me. Somehow the wedding arrangements were expedited and I didn’t even have time to learn more about my husband. Later I understood why his family was in such hurry. I don’t want to talk about this period of my life. I don’t even want to pronounce the name of my first husband. He turned out to be mentally retarded, but nobody ever mentioned this to me before the wedding. We had a short civil ceremony in the registry office, a small dinner party for the closest relatives in the evening and left for Chernovtsy. Bukovina was annexed to the USSR in 1940, and Chernovtsy seemed a real European town to me. It was a very cozy and clean town with wide streets. Chernovtsy was a Jewish town: before the war the Jewish population constituted about 60% of the total population. There were fewer left after the war: some perished and the others moved to Romania and Palestine. However, many Jews stayed: they spoke Yiddish in the streets, synagogues operated and there was a Jewish Theater. I went to all performances. I liked the surrounding of reserved, polite and well-dressed people. Jews often went to the theater and all performances were sold out. There were also non-Jewish theater goers, though all performances were in Yiddish, of course, but non-Jews could understand and even speak Yiddish well. I went to work as an agronomist to the kolkhoz 18 in Novoselitsy village near Chernovtsy. Commuted to work by bus. My husband and I lived several years together being absolute strangers to one another. I divorced him and the management of the kolkhoz submitted a solicitation to the executive committee 19 for providing lodging to me. I received a small room in a shared apartment 20. I was happy to have a place to live.

I think anti-Semitism developed after the period of struggle against cosmopolitans 21, and the ‘doctors’ plot’ 22. When the period of struggle against cosmopolitans began I did not give much thought to what was going on. I believed that those people were guilty like I believed everything the communist party was doing and never allowed one doubt about them. At that time the Jewish theater and school were closed. When in January 1953 the period of the ‘doctors’ plot’ began and the first article was published indicating the names of the doctors who wanted to poison Stalin, my first thought was that this was nonsense, but many people took it very seriously. People refused to go to Jewish doctors and later they began to say that Jews could not be trusted anyway. Anti-Semitism was growing stronger. Jews were abused in the streets just for being Jews, but this was done by newcomers from the USSR. I never tied what was happening to the name of Stalin. I never thought he could initiate it. There were talks about deportation of Jews to Siberia or the Far East. At that time I thought this to be an evil fib of somebody, but later I understood that Stalin’s death prevented this from happening. There was nothing monster could not do! When Stalin died on 5 March 1953 we all cried. Everybody loved him and could not imagine life without Stalin. When at the 20th Congress of the party 23 Khrushchev 24 spoke about Stalin’s crimes, I was horrified, but I believed what Khrushchev said at once. I knew about the tragic fate of Stalin’s son Yakov Djugashvili and I did not doubt that a man, who could do this to his own son [During the war Yakov Djugashvili, a private of the soviet army, was captured and Germans offered to exchange him for a German general. Stalin said to this: ‘we do not exchange privates for generals’. His son perished in captivity], could exterminate people who were smarter and better than he. Stalin killed his most honest and devoted comrades, dedicated communists like Trotskiy 25, Kamenev 26, Zinoviev 27 and many others. His goal was ultimate power and he walked toward it over dead bodies of those who opposed him. He also exterminated common people far from politics or struggle for power. I understood how crafty and cruel Stalin was. However, the crash of my belief in Stalin did not alter my belief in Lenin 28. I still believe Lenin to be a great personality and admire him.

I worked in Novoselitsy until 1959. Then I got an offer of the position of a scientific employee in the All-Union scientific research institute of potato farming, its affiliate in Chernovtsy, where I worked in the department of potato farming till 1983. The institute had its experimental fields where I spent much time. Farming is hard work, but I liked my job. I didn’t face any anti-Semitism. I got along well with my colleagues. We were like a family. We celebrated Soviet holidays and birthdays together. My colleagues were my friends and my family. I always spent my vacations in Mogilyov-Podolskiy. I stayed with my mother and saw my brother, sister and school friends every day.

In 1976 my mother fell severely ill. My brother’s death struck her hard and her heart condition grew worse. My sister and her family looked after her. My mother died in 1977. I came to see her in Mogilyov-Podolskiy before she died. She was buried beside my brother’s grave in the Jewish cemetery in Mogilyov-Podolskiy. Before she died mama asked us to bury her according to the Jewish tradition and we fulfilled her will. Older Jews, who knew all rules made all necessary arrangements. There was a rabbi from the prayer house at the funeral.

In the 1970s numbers of Jews began to move to Israel. Many of my acquaintances from Mogilyov-Podolskiy and Chernovtsy went there. I sympathized with those people. Every person must have the right to make his own choices. Of course, from the official point of view they were traitors, but common people thought different wishing them happiness and luck in their new life. My mother’s sister Haya, her husband and their three daughters moved there. Haya and her husband have passed away, but their daughters and their families live in Israel. My colleague and friend moved to Israel. We corresponded before she left and we still correspond. Considering my health condition I am not going to move to Israel. My doctors said I should not change the climate. I would move there if it were not for this circumstance. I wish peace and calm came to Israel, this little beautiful country surrounded by enemies.

I met my second husband Lev Gershenzon, his Jewish name is Leib, when I was on vacation in Mogilyov-Podolskiy. He was a teacher of chemistry at an evening school. Lev was born in 1914 in Shargorod town of Vinnitsa region [about 350 km from Kiev]. Shortly after Lev was born – before the revolution - his father Abram Gershenzon moved to USA. He didn’t have any contacts with his family. Lev was the youngest of all children. He had two older brothers: Moisey and Aron. Lev’s mother died from typhus in 1918. Their relatives sent Moisey to a children’s home. Aron was raised in his uncle’s family and Lev was raised by his grandmother. Lev finished 8 forms of the 8-year Jewish general education school in Shargorod and went to Vinnintsa to continue his studies. He worked as a loader at the railway station during a day and in the evening he attended a rabfak school. He finished the rabfak with honors and was sent to the Chemical Faculty of Odessa University. He lived in the dormitory. To earn his living he unloaded railcars at night. Lev finished his college with honors and got a job assignment 29 to work as a teacher of chemistry and biology in the Jewish general education school in Chernivtsy Vinnitsa region [about 300 km from Kiev] where he married a local Jewish girl. In 1938 their daughter Sophia was born. My husband’s older brother Moisey lived in Shargorod where he worked as an electrician. He was married and had two children. Aron wanted to become a pilot. After finishing school he entered Kiev pilots’ school. When the war began, my husband’s brothers went to the front. Moisey was wounded in 1944. He was taken to a rear hospital. When he recovered he returned to the front line forces. He was in Czechoslovakia, when the war ended. When he returned he was a severely ill man. He never recovered completely from his wound. He died in 1946. He was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Shargorod. Aron was a military pilot. In 1943 he perished fulfilling his combat duty.

Lev and his family stayed in Chernivtsy. Soon after Chernivtsy was occupied Germans gathered all Jewish and Ukrainian communists, took them out of the village and ordered them to dig pits. When the pits were ready they buried people alive, left one young guard to watch the area and left. The villagers brought this guard gold and whatever valuables they managed to get to allow them to rescue any survivors. Some of those who were nearer to the surface, including Lev, survived. He could stay no longer in Chernivtsy for the fear of being reported to Germans and he left the village at night. Lev knew about the ghetto in Mogilyov-Podolskiy and thought he might go there to get lost among the people who did not know him. Some time later somebody reported on him that he was a communists. He was taken to interrogations where he was terribly beaten. It was fortunate for him that those were Romanians guarding the ghetto for Germans would have killed him for sure. He was taken to hospital as if to get treatment after these beatings, but actually there were experiments conducted on its patients. It became known recently. My husband receives monthly compensation nowadays. The Soviet army liberated the ghetto in March 1943. Lev returned to Chernivtsy. His wife and daughter were in Chernivtsy and managed to survive. Lev went back to his work. The Jewish school of Chernivtsy was closed after the war in 1945. Lev and his family moved to Mogilyov-Podolskiy, where he went to work as a teacher of chemistry and biology in a Ukrainian general education and evening schools. Lev was highly valued at work. In 1947 his son Mikhail was born in Mogilyov-Podolskiy. In the late 1950s doctors discovered that his wife had cancer. She had a surgery, but it didn’t help. She died in 1960. His daughter entered the Faculty of physics and Mathematic of Vinnitsa University. Lev was raising his son. After finishing school Mikhail entered the Krasnodar Medical College in Russia. It was hard for Jews to enter colleges in Ukraine at that time, when anti-Semitism was growing stronger. When I met Lev, he lived alone. After finishing the Medical College his daughter got married. She and her husband moved to Balashikha town near Moscow. She worked as a doctor in a hospital and her husband was an engineer at a construction site. His son got married after finishing his college and stayed to live in Krasnodar.

I returned to Chernovtsy. Lev and I corresponded. When I came to Mogilyov on another vacation we got married. We were no young any more and we didn’t have a wedding party. We registered our marriage and had a small dinner in the evening. Our guests were my sister and he husband and my husband’s few friends. I exchanged my room in Chernovtsy for lodging in Mogilyov-Podolskiy, and moved there in 1983. In Mogilyov-Podolskiy I went to work as a lab assistant at the quality assurance laboratory of the agricultural machine building plant and from there I retired in 1993. We didn’t celebrated Jewish holidays. We celebrated Soviet holidays at home: 1 May, 7 November 30 Soviet army Day 31, Victory Day 32, and New Year. We had guests at home and visited friends. My husband’s friends were his colleagues from school. His former students who remembered their teacher came to see him. Lev worked at school till 2002. He had turned over his retirement age, but he did not want to quit his job. In 2002 a car hit my husband. He had a craniocerebral trauma and he could work no longer. My sister and her family moved to USA in the early 1990s. They live in New York. My sister and her husband are pensioners. Her son and daughter have their own families. They are doing very well. My sister sends me money and calls me. I am glad that she is well, but I would lie to have a close person nearby. My husband or I have no relatives in Mogilyov-Podolskiy.

At the beginning I felt indifferent about the perestroika 33, in the late 1980s initiated by Mikhail Gorbachev 34 Later, when enterprises were closing up and people started having financial problems, this indifference grew into aversion of what was going on. Perhaps, perestroika resulted in something good for some people, but we, older people, see no good in it. I still feel sorry about the breakup of the USSR that perestroika resulted in. I don’t think they had to destroy what the revolution created. It was a great and powerful state that cared about its citizens, while now we have a number of ‘independent’ states ruled by poverty and confusion. Common people want to be sure of tomorrow and need free medicine and education. There was no unemployment during the socialist period, but now, it seems, there are more unemployed than working people. Even those who have jobs have no stability. I don’t think this can last long. I think we should unite and restore the USSR. And I think this will happen in the near future.

The only positive thing in independent Ukraine seems to be the reviving Jewish life. A synagogue and a Sunday Jewish school for children opened in Mogilyov-Podolskiy. When Hesed 35 and the Jewish community started their activities, our life started improving. Hesed and the Jewish community help us to survive. Hesed provides food packages and the necessary medications. There are visiting nurses helping older people about the house. This is a great support and I don’t know how we could live without it. There are many Jewish newspapers and magazines issues. I read many of them and learn many interesting things from them. I used to take part in community life. There were good concerts of Jewish music and dances. People got together to celebrate Sabbath and Jewish holidays. Presently I cannot leave my husband for a long time and I cannot attend those events, but we can always have the care and attention we need.

1 Jewish Pale of Settlement

Certain provinces in the Russian Empire were designated for permanent Jewish residence and the Jewish population was only allowed to live in these areas. The Pale was first established by a decree by Catherine II in 1791. The regulation was in force until the Russian Revolution of 1917, although the limits of the Pale were modified several times. The Pale stretched from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea, and 94% of the total Jewish population of Russia, almost 5 million people, lived there. The overwhelming majority of the Jews lived in the towns and shtetls of the Pale. Certain privileged groups of Jews, such as certain merchants, university graduates and craftsmen working in certain branches, were granted to live outside the borders of the Pale of Settlement permanently.2 Russian Revolution of 1917

Revolution in which the tsarist regime was overthrown in the Russian Empire and, under Lenin, was replaced by the Bolshevik rule. The two phases of the Revolution were: February Revolution, which came about due to food and fuel shortages during World War I, and during which the tsar abdicated and a provisional government took over. The second phase took place in the form of a coup led by Lenin in October/November (October Revolution) and saw the seizure of power by the Bolsheviks.3 Civil War (1918-1920)

The Civil War between the Reds (the Bolsheviks) and the Whites (the anti-Bolsheviks), which broke out in early 1918, ravaged Russia until 1920. The Whites represented all shades of anti-communist groups – Russian army units from World War I, led by anti-Bolshevik officers, by anti-Bolshevik volunteers and some Mensheviks and Social Revolutionaries. Several of their leaders favored setting up a military dictatorship, but few were outspoken tsarists. Atrocities were committed throughout the Civil War by both sides. The Civil War ended with Bolshevik military victory, thanks to the lack of cooperation among the various White commanders and to the reorganization of the Red forces after Trotsky became commissar for war. It was won, however, only at the price of immense sacrifice; by 1920 Russia was ruined and devastated. In 1920 industrial production was reduced to 14% and agriculture to 50% as compared to 1913.4 Pogroms in Ukraine

In the 1920s there were many anti-Semitic gangs in Ukraine. They killed Jews and burnt their houses, they robbed their houses, raped women and killed children.5 Gangs

During the Russian Civil War there were all kinds of gangs in the Ukraine. Their members came from all the classes of former Russia, but most of them were peasants. Their leaders used political slogans to dress their criminal acts. These gangs were anti-Soviet and anti-Semitic. They killed Jews and burnt their houses, they robbed their houses, raped women and killed children.6 Denikin, Anton Ivanovich (1872-1947)

White Army general. During the Russian Civil War he fought against the Red Army in the South of Ukraine.7 Struggle against religion

The 1930s was a time of anti-religion struggle in the USSR. In those years it was not safe to go to synagogue or to church. Places of worship, statues of saints, etc. were removed; rabbis, Orthodox and Roman Catholic priests disappeared behind KGB walls.8 Rabfak (Rabochiy Fakultet – Workers’ Faculty in Russian): Established by the Soviet power usually at colleges or universities, these were educational institutions for young people without secondary education. Many of them worked beside studying. Graduates of Rabfaks had an opportunity to enter university without exams.

9 Jewish collective farms: Such farms were established in the Ukraine in the 1930s during the period of collectivization.