a

Bertha Trachtenbroit

Odessa, Ukraine

Interviewer: Natalie Fomina

I was born in the town of Odessa on 31 May 1924.

My grandmother on my mother’s side Surah-Leya Genehovna Kluch was born in Vitebsk (1) (1,000 km-s from Odessa) in 1856. I don’t know my grandmother’s maiden name. Her father owned a tavern in Vitebsk. Their family was wealthy. My grandmother told me that she catered for their visitors there. They were locals and travelers. They called my grandmother Sonia that was a more familiar name for them. They were served vodka and snacks. My grandmother used to joke “that’s why I’ve lived a long life and had perfect health - because I’ve always had a shot of vodka before dinner”. My grandmother’s parents were religious and celebrated Saturday. My grandmother had a religious education in her family. She could pray in Hebrew and knew the kashrut requirements. My grandmother told me that on Saturday and Jewish holidays her father had a Belorussian shabesgoy working in the tavern in the place of the father. From 1924 when I was born my grandmother lived with us. She always wore a long, dark skirt and kerchief, (a wig she did not have). On Saturday and holidays she went to the synagogue not far from our house. She cooked delicious traditional food: tzymes (2), chicken broth, stuffed necks of hen or goose and meat with prunes. Only we could very rarely afford meat and most of the time we ate a vegetarian stew. When she made small pancakes my brother and I tried to steal them when they were still on the pan. Grandmother slapped us on our hands telling us to be patient and wait until she had them ready on the table for us. Grandmother always spoke Yiddish to her daughters. That’s how I learned my mother tongue. Grandmother died in September 1941 at 85, one month before Odessa was occupied by the Rumanians.

My grandmother’s husband Haim Kluch was born to a poor Jewish family somewhere in Byelorussia in the 1840s. He was a retired soldier of Nikolay’s army (3) - he was a cantonist (4). Jewish boys 8-9 years of age who came from poor families of were taken to the army to become cantonists and serve 25 years. They were forced to accept Christian faith, but my grandfather Haim remained faithful to his own religion. Grandfather's service term ended in Pskov where he was given the social status of a bourgeois. Pskov province was outside the Jewish Pale of Settlement (5). According to the census of 1858 there were only 244 Jews living in Pskov and most of them were retired soldiers. I think that my grandfather stayed in Pskov for a short time, while he was still in the army and then he returned to Vitebsk after his service was over and met my grandmother. He was much older than my grandmother since he had served 25 years in the tsarist army. They got married some time in the 1870s. My grandfather was a musician and played at Jewish weddings. Later they moved to Elisavetgrad (6) and then to Odessa. I don’t know exactly when they moved but their younger daughters beginning from Kreina (1891) were born in Odessa. I don’t know anything about their house in Odessa. Grandfather Haim died in 1919. People said he was a lucky man because when he died all their 11 children and grandchildren were alive. After his death several members of the family died or perished during the civil war (1918-1920).

My grandparents had 11 children: five sons and six daughters. The boys studied at cheder and grandfather taught them music. The girls received primary education and studied profession when they turned 12. Kreina, Betia and Rosa finished a Russian primary school (4 years) in Odessa where they studied Russian language and arithmetic. Where did the older girls study I don’t know. The older children went to work to help the family. They were not rich, but they were not poor either. They celebrated Shabbat and all Jewish holidays. They followed the kashrut. The children were raised in a religious spirit, but the post-revolution propaganda had a great impact on their outlook. Religion was persecuted and synagogues were closed. In the course of time my grandparents’ children stopped observing the traditions of their people. My mother never spoke to me about how they observed Jewish traditions.

Feiga, the oldest sister, was born in 1875. I don’t remember Feiga’s husband. I know that his name was Shymon Sutorianskiy. Feiga was the only one of my mother’s brothers and sisters that observed Jewish traditions all her life. On Friday she lit two Shabbat candles. She went to the synagogue on holidays. Feiga had 6 children: 4 daughters (Rosa, Zhenia, Betia and Sonia) and two sons (Mark and Solomon). Feiga was a housewife and lived with her older daughter Rosa when she grew older. Rosa’s husband Mikhail (Mosha) was a carpenter. They were well off. Feiga’s 2nd daughter Zhenia married a Brazilian Jew during the revolution of 1917. He was a circus actor. In 1918 their daughter Anya was born. They all left for Brazil in 1919. Feiga’s daughter Betia moved to Brazil in 1924. She died in Rio-de-Janeiro in the 1960s. She had two daughters, but I don’t know anything about them. Feiga’s youngest daughter Sonia lived in Odessa. The sisters kept in touch before the war. They stopped corresponding with each other later in the 1930s when it was not safe to keep in touch with relatives abroad (7). Feiga died in 1947. In the 1960s Zhenia visited her sisters Sonia and Rosa in Odessa. I saw her then. She spoke Russian. In the 1970s her daughter Anya visited Odessa. She could only speak Yiddish. Zhenia died in the late 1970s. Anya is 84. She married a diplomat from Panama and she lives in Panama. In 1975 Feiga’s youngest daughter Sonia moved to the US with her daughter, son-in-law and grandchildren. Sonia died in the 1980s. Her daughter Maya lives in New York. We talk on the phone with her. Feiga’s eldest daughter Rosa died in Odessa in 1975. Her daughter, husband and son and their father moved to the US in the late 1970s. Feiga’s son Mark was a journalist. He worked in Moscow and Odessa. In the late 1960s he moved to the US. I have no more information about him. Solomon perished at the front during the war.

My mother’s older brother Abram was born in 1876. Long before the revolution of 1917 he left for St.-Petersburg. My grandfather’s children had the right to enter higher educational institutions and had no residential restrictions. This was the right granted to all soldiers of Nikolay’s army. Abram was a musician. He worked at the Leningrad Maly Opera Theater for many years. One of his daughters – Rita – also worked in this theater as a choirmaster. Abram was married twice. He had 5 children, but I didn’t know them. He died in the 1950s.

My mother’s brother Mikhail was born in 1878. He was a drummer in an orchestra in one of the theaters in Odessa. His wife Olga was a Jew. She had two children from her first marriage. I didn’t know them. Somebody told me that once Olga found a bomb in her daughter Adel’s bag. This happened before the revolution of 1917. Adel was a revolutionary. After the revolution she and her brother became high party officials. Adel lived in Moscow. Aunt Olga’s son -- I don’t remember his name -- served in the I. Yakir’s headquarters (Editor’s note: Yakir was a member of the Soviet Communist Party since 1907, one of the founders of the Communist Party in Ukraine. In 1938 he was arrested and executed.) during the civil war of 1918-1920. Adel and her brother were arrested in the end of 1937 (8). Mikhail stayed in Odessa during the war and perished in the ghetto in 1941 and so did his wife.

My mother’s sister Klara (Khaya) Psakhis was born in 1880. I know little about her. She lived in Odessa. She had a daughter Manya. During the war she was in evacuation in Tashkent. She died in the late 1940s.

My mother’s sister Zhenia (Genia) was born in 1882. My mother told me that Zhenia looked after her younger sisters. She taught them to clean the house and wash the floors. They had chores at home when they were 5-6 years old. Zhenia’s husband Solomon Zelterman died of tuberculosis in 1908, a few months before their only daughter Shlima was born. Zhenia worked at the R. Luxembourg confectionery factory all her life. She was a laborer there. Aunt Zhenia was a member of the Communist Party. She didn’t observe any Jewish traditions. She died in the 1950s. Shlima has 3 children. Two of them (Lena and Konstantin) are in America.

Another brother Jacob, born in 1885, was a musician. In 1919 he was in the orchestra of a (communist) propaganda group that made the rounds of villages in Kherson province to propagate for the Soviet power. The orchestra played the International (9) and other revolutionary songs. In the village of Bolshoy Buyalyk they were attacked by a gang (10). They shot members of the propaganda group and told the musicians to separate into two groups: Jews in one group and Ukrainians and Russians in another. All Jews were shot and their bodies thrown into a well. I knew Jacob’s widow Zhenia (her Jewish name was Shprintsa). They had two sons: Ilyusha and Misha. Shprintsa was a member of the Communist Party. She didn’t observe any Jewish traditions. In the early 1930s in the process of collectivization in Ukraine Jewish collective farms (11) were formed. Shprintsa became chairman of one of them. In 1937 she was expelled from the Party and dismissed from work. She didn’t have a job afterward. She earned her living by sewing. She made all our clothes. Shprintsa’s older son Ilyusha perished at the front during the war. After the war she lived with her younger son Mikhail. He graduated from Odessa Communications Institute and moved to Sevastopol. Shprintsa died few years after the war.

All I know about my mother’s brother Isaac is that he was born in 1897. I only knew his wife. He died of some disease around 1925. I heard that Isaac had studied abroad, but I don’t know for sure.

I know about my mother’s brother Lazar only what my aunts told me. He was born in 1890. He never married. He was very fond of sewing and made dresses for his sisters. I don’t know what he did for a living. He died of some disease (probably typhoid) in 1920 during the civil war.

My mother’s sister Katia (Kreina), born in 1891, was very talented. She finished primary school with all highest grades and the director of the school offered her to continue her education in a high school at no cost. Her mother was only supposed to buy her a school uniform and textbooks. (But her mother said that she didn’t have money for that and this was true. Kreina went to work. When I knew her she was a housewife and her husband provided for her. They had two children: a son and a daughter. Their son graduated from the Communications Institute in Odessa in the 1930s. He has a wife and two children. They all live in Moscow now. Katia died in evacuation in Fergana, Uzbekistan (3,000 km from Odessa) in 1943 and her husband remarried. Her daughter stayed in Fergana after the war.

My mother’s sister Betia was born in 1894. Her husband Solomon Bochkur and she sold food products at the Privoz market (Editor’s note: the biggest food market in Odessa). I don’t know whether they owned the food stand or they were employed by its owner. They had two children. Their older son Haim was born in 1921. He got married after the war and lived in Odessa. He died in 1995. His brother Anatoliy moved to America 20 years ago and lives in Los Angeles. Betia and Solomon always supported our family. When in the 1930s education in high schools was to be paid for Solomon paid for my brother Leonid and me to get education. During the war he was in evacuation, but I can’t remember where. Betia died in Odessa in the late 1950s. Solomon remarried and we lost contact with him.

My mother Rosa Kluch, the youngest in the family, was born in Odessa in 1896. She finished primary Russian school where she learned to read, write and count. I remember my mother’s certificate from this school. It was issued to “the daughter of Nikolay’s soldier Kluch Rukhlia Haimovna”. In her passport her name was written as Rosalia Efimovna. I guess she must have changed her name in the early 1920s for a more common one. She was called Rosa in the family. She started her professional education at 12 when she became the apprentice of a corset maker. Mother lived then with his family in their house. My mother told me that she mainly did all kinds of house chores and small errands. She went to the market with the master of the house where she was carrying a basket where he put the food products that he bought. She remembers how he bought her sweet water with gas. It was fun. She also learned to do minor things like sewing ribbons and laces on corsets. She remembered them as nice people. She didn’t stay there long. In 1908 Shlima, my mother sister Zhenia’s daughter was born. My mother was so eager to look after the baby that she ran away from the corset maker. For about two years she lived with her elder sister and helped her in the house. Some time later she got a job at the Vysotskiy tea factory (Editor’s note: K. Vysotskiy founded the biggest tea company in Russia. He contributed much to charity.), where she worked for about 10 years. Once my mother met a young man. She lied to him saying that she was working for a dressmaker, because having a job at a factory for a girl was not what young men at that time really appreciated. The mother of this young man owned a cinema theater in Moldavanka (12). My mother’s boyfriend often took her to the cinema. Once he saw my mother coming out of the gate of the factory and terminated their relationships.

My father’s family came to Odessa from Kishinev. I don’t know why or when they moved to Odessa (13). I only know that it happened before 1894, as my father was born in Odessa in 1894.

My grandfather on my father’s side Abram Trachtenbroit was born in Moldavia in the 1860s. He was very religious. He finished cheder. He only spoke Yiddish. He wore a long black jacket, a black waist jacket, a cap outside and a yermulka at home. He had a beard and short payot. When he prayed he covered his head and shoulders with thallith. He was a gabbai in the synagogue. My grandmother Surah-Leya attended this synagogue. Grandfather Abram was a painter and all his sons had this profession. Before the revolution of 1917 he earned his living by refurbishing apartments and his sons did this work with him. After the revolution of 1917 grandfather and his sons continued to work as painters. My grandparents’ family was wealthy. Grandfather Abram was rather greedy. When he visited us he gave my brother and me 3 Kopecks each. One could buy 3 sweets for this money, but in his opinion it was a lot. When he took a nap he put his wallet under the pillow. Grandmother used to take his wallet out of there when he was asleep and give us some money. Once she gave us 3 rubles and we bought a doll that became my favorite toy. Grandfather always kept his money tied to his belt. He used to say that all his savings were for his grandchildren. One day(in 1933) he fainted in the synagogue, fell down and died. And somebody grabbed all his savings from his waist. He was buried according to the Jewish rituals, but I did not attend his funeral.

My grandmother on my father’s side Hana was born in Moldavia some time in the 1860s. I know nothing about her family or education. I don’t know her maiden name either. When I knew her she was a housewife, but according to what I heard from other members of the family she had been a dealer before the revolution (of 1917). She purchased hay, grain, wheat, etc. from farmers and sold these to vendors. She observed all Jewish traditions and celebrated all holidays. She went to the synagogue on Saturday and on holidays. She always wore a kerchief but she had no wig. She always wore a long, dark skirt. She spoke Yiddish at home. After grandfather Abram died Hana lived with her daughter Anya’s family. Grandmother perished in the Odessa ghetto in 1941. My grandparents had 4 sons and a daughter.

My father’s older brother moved to America long before the revolution and I don’t know anything about him.

My father’s sister Anya was born in 1892. Anya was two years older than my father. According to the unwritten Jewish law my father wasn’t supposed to get married before his older sister did. Anya had a fiancé but my father didn’t want to wait until they got married. For this reason my grandmother didn’t come to his wedding, although she always treated my father’s wife and us, children, very kindly. I don’t know whether she had any education or what she did for a living. She was married but they didn’t have any children. She and her husband Mikhail, observed all Jewish traditions and celebrated Jewish holidays. I remember Mikhail but I don’t know what he did for a living. Mikhail died before the war and Anya perished in the ghetto in Odessa in 1941.

My father Solomon was the third child in the family.

The next son was Berum (Boria) and he was born in 1895. He studied in a cheder and was a painter like his father. He died in a car accident in the early 1930s. He had a wife (Fania) and two children: a son Leonid and a daughter Sonia. Fania died in the late 1950s. Leonid and Sonia moved to the US in the 1990s.

Lev, the youngest brother, finished cheder and worked as a painter like his father. He had a wife and two daughters: Sonia and Manya. After his father died he worked as a carpenter. He perished in the ghetto in Odessa along with his mother and sister Anya. His wife and daughters were in evacuation, but I don’t know where. After the war they returned to Odessa, but we didn’t keep in touch with them.

My father Solomon Trachtenbroit was born in Odessa in 1894. He finished cheder like all the other boys in the family. I know little about my father because he left my mother when I was 7. He worked as a painter like his father and was very good at renovating apartments. Later he was a clerk at the Jewish Clerks’ Support Community of Odessa and then became involved in commerce. I don’t know where or how my parents met. I only know that they met when my father was a clerk and my mother worked at the tea factory. They got married on 5 February 1919. They had a traditional Jewish wedding with a huppah. The ceremony was conducted by a rabbi from the synagogue where my grandfather was a gabbai. There were many guests at their wedding besides their brothers and sisters and their families. The newly weds settled down with my mother's sister Zhenia in her apartment in Staroportfrankovskaya Street. Zhenia was a very imperious woman. She was called a general governor in the family. There was a story told in the family. One morning Zhenia opened the window shutters. My father closed them. Zhenia opened them again and my father closed them. Zhenia packed her belongings, took her daughter and they moved to Zhenia’s sister Katia that lived in the next-door apartment. We lived in Zhenia’s apartment until the war. It was a 2-room apartment. My mother quit her job after getting married. She could afford to stay at home. My father provided well for the family.

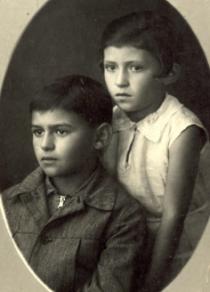

My mother had a baby girl that died of whooping cough when she was 3 months old. My brother was born in 1921. Grandfather Abram named him after his deceased brother Leibush but in his birth certificate his name was written as Leonid. By the way, here is what happened during the issuance of his birth certificate. Shlima, Zhenia’s daughter, was told to go and pick it up at the registry office. She didn’t check it and the last name of Trachtenbroit was misspelled and Leonid’s last name was written as Trachtenburg. I was born in 1924. According to the Jewish tradition my mother’s relatives were to name me. They had a deceased relative named Bunia. They called me Beba (the first letter in both names is the same) and in my birth certificate I had the name of Bertha. Grandfather Abram wanted to name me Inda like my mother. It’s a rare and beautiful name. Grandfather went to the synagogue and they put down the name of Inda for the newly born baby in their books. Grandfather always called my brother -- Leibush and me – bobe Inda (Yiddish: Granny Inda). He only spoke Yiddish. He always asked me “Vos hert zikh, bobe Inda?” (Yiddish: What’s new Granny Inda?”). That is how I happened to have different names in my passport and in the books at the synagogue. I prefer to be called by my Jewish name. When I was born our grandmother Surah-Leya moved in with us. She lived with aunt Klara before.

My first memories about my childhood go back to our stay at the dacha (summer house) in Lustdorf (Editor’s note: village on the seashore near Odessa). We rented a house there because my father was manager of a food store in this town. It wasn’t a big store, but there were all general consumer goods and food products there. Our landlord was German. I remember a roofed well in the yard. My brother threw my favorite plastic doll on the roof of the well and I was afraid that I had lost it. Our landlord used to stroll in the yard saying „Das ist mein Haus. Das sind meine Bäume. Das ist mein Brunnen“ (This is my house. These are my trees. This is my well.) Once he picked my doll from the roof of the well and I was so happy that he had found it. I also remember that portrait of Trotsky hanging on the wall of our house. Trotsky was as popular as Lenin in the 1920s. Once in 1929 my father came home from work and said that we had to take off the portrait. This happened in 1929 when Trotsky was deported from the country. I heard Stalin’s name for the first time in 1929. I was 5 years old then. I was visiting our neighbor Tsylia and somebody said there that it was Stalin’s birthday and he was to turn 50. Tsylia said joking, “Well, I’ll mail him two kettles”. Kettles were of a big value then.

In 1931 our father left us for a cashier woman from his store. Her name was Lyuba and she was a Jew. They moved to Moscow. He married Lyuba in 1933 and in 1935 his daughter Iraida was born. He was involved in commerce. During the war he lived in Moscow. He became a member of the Communist Party during the war and was awarded a medal “For the Defense of Moscow”. This medal was awarded for heroic deeds at the front and for labor in the rear. My father was chief of Trade Department at Kaliniskiy District Committee in Moscow. He kept in touch with my brother Leonid and me. We went to Moscow and met him. My father died in Moscow after a 2nd heart attack in 1966. I went to his funeral. I still communicate with my stepsister Iraida.

After my father left us the situation in the family grew worse. My mother had to go to work. Zhenia helped her to get employment at the confectionery factory. She was a packer. Our apartment was one of the best in or building. The house belonged to a landlady. Her name was Volovelskaya. When she came to pick up the rent she always complained to my mother that our fee was very low and she should charge us more for what she called “this royal apartment”. We had running water and a toilet in this apartment. We had a table, few chairs, beds and a bookcase. My father left us his collection of books: fiction and classics. The only beautiful piece we had was a table lamp: a big ball on a marble stand. My aunts had a Singer sewing machine. We had old ironing accessories in my early childhood. We had a copper mortar and pestle and a kettle. We also had a copper bowl to make jam. But I don’t remember any jam – these were difficult and needy years. I remember how we made cherry drink (put cherries in a big bottle with a narrow neck and added sugar and left it until the drink was ready).

In 1932 – 1933 there was a famine in Ukraine (14) forced by Bolsheviks. We were also hard up because my father left us at that period. The only valuable thing of his that we had was his stick with silver monograms. It was given to him by his colleagues at some anniversary. My mother removed all silver monograms and took them to the Torgsin store (15). She bought 1.5 or 2 pounds of semolina for this money. In 1933 my mother got a job at the canteen of the Cultural Center for Railroad Employees named after Ivanov. They sold cakes in this canteen. We survived thanks to these cakes. I remember a day when I didn’t have any food all day and fell asleep hungry. My mother woke me up late at night to give me a cake. We received rolls at school and our teacher watched that we ate them ourselves rather than took them home. Betia often brought us some cereals or flour. Members of our family supported each other and nobody starved to death.

There was a cemetery near our house. Leonid’s friend was the son of a cemetery warden – Valka. We always played at the cemetery. There was the sepulcher of Vera Kholodnaya, an outstanding actress of silent movies. I also remember the monument of General Radetskiy, a hero of the Russian-Turkish war of 1888. There were cannons and chains around the monument. We enjoyed swinging on these chains. I also remember gravestones with snails crawling on them. There were many lilac bushes. We enjoyed playing there.

We spoke Russian in the family. My parents never spoke to us, the children, in Yiddish, but to the elder generation did. Our grandparents communicated with their children and grandchildren in Yiddish, therefore I understand the language till today. As far as I remember my parents did not observe any of the Jewish holidays. Instead, we celebrated the family holidays and Soviet holidays just as the families of my Jewish and non-Jewish friends. My grandmother Sura- Lea went to the synagogue but she never took me as a girl along.

There was Russian, Ukrainian and Jewish population in our neighborhood. All neighbors communicated in mixed, Russian,Yiddish and Ukrainian. There were many interesting people around. I remember a midwife. She was a Jew. Her last name was Vexler. She always had a bag with her. She assisted my mother when I was born. When we met she said to me “I bought you from the gypsies” and I replied “Gypsies can’t be red head”. I also remember a pediatrician, a Jew called Nutis. He treated all our children’s diseases: measles, whooping cough and scarlet fever. There was a hairdresser’s on the ground floor in our house. I remember the hairdresser Perchik – also a Jew. He had a wife Manya and two children: Sarah and Juliy. Sarah was my good friend. They failed to evacuate at the beginning of the war. They all perished. They were burned at the gunpowder storage facilities. Another sad memory about the family of my friend Shlima. Their family name was Dubossarskiye. They had 6 children. Shlima’s mother was very religious. I remember how she fasted at Yom Kippur in 1940. She came home from the synagogue, kissed all her children and wished them a long life. In autumn 1941 they were all shot in Dalnik (16).

I went to a Ukrainian secondary school (which also included an elementary school) in 1932. I could read and write then. My brother studied at this school. When he was to go to school in 1929 he was offered to go to a Jewish school, but our mother understood that it was advisable to go to a Russian or Ukrainian school if someone wanted to continue his studies. Teaching in higher educational institutions was conducted in Russian and Ukrainian. Besides, my brother didn’t know Yiddish – he did not spend as much time with my aunts as I did. My mother went to the district department of education and they suggested that he went to a Ukrainian school. That was how he went to this Ukrainian school. It was a very good school. Our teachers were very good. I was one of the best pupils there. I remember my first teacher Matryona Illarionovna Khomenko, a Ukrainian. I also remember our German teacher Bertha Israilevna. She was a Jew. I remember Boris Zdanevich, our teacher of the Ukrainian language and literature. I enjoyed studying and have very pleasant memories of the years I spent at school. I liked Ukrainian language and literature classes best of all. I became a pioneer and then a Komsomol (17) member at school. I was never really active socially and I tried to participate in the pioneer and Komsomol activities only formally. I preferred to stay at home and read books.

I had many friends of various nationalities. I can’t remember one single demonstration of anti-Semitism at school. My best friend was Rachel Torgova, a Jewish girl. We were sharing the same desk from the 1st till the 9th form. Rachel was a very talented girl. She was especially good at mathematics. Rachel`s mother was sick, bed-ridden, so it was she who visited me more often. We studied together and walked a lot on the sea- side. During the war she was in evacuation in Semipalatinsk with her mother and sister. Her father perished at the front. After they returned from evacuation Rachel had to support her ill mother and she had to go to work. She finished an accounting school and worked as an accountant. Her younger sister Fenia got married and left Odessa. Rachel never got married. In 1995 she moved to the US with her sister’s family. She lives in San Francisco now. We phone each other regularly.

During the Stalinist repressions only Mikhail’s relatives and Jacobs widow Shprintsa suffered in our family. Two of our schoolteachers were arrested in those years. I was wondering then whether all those people that were arrested and declared enemies of people could have been guilty.

My mother didn’t remarry after our father left. She spent all her time with us. She wanted her children to get a higher education. In 1939 my brother finished secondary school. He was very fond of literature. He read a lot and composed poems. He was going to enter the Philology Faculty at the university. However, my brother and his classmate Mikhail Shichtman were requested to come to the military registry office where they were offered to go to the Navy College. This was the so-called Voroshylov admission (19). For the sake of their future career they couldn’t refuse this offer. They both entered the Higher Navy College in Sevastopol and finished 2 years before 1941 when the war began. My brother bought me a knitted woolen shawl from his first stipend. I still have it. Two or three days before the war started my brother’s training boat stopped in Odessa and we managed to see him. He came home for the last time in the evening of 21 June.

My mother was at work in the factory and he didn’t see her. I went to the port with him and he promised to come again in the morning. And on the next morning the war began. Our neighbor’s boy ran to the port and got to know that my brother’s boat left for Sevastopol. In 1941 my brother was in a marine unit in the Northern Caucasus. In March 1942 he was severely wounded in his chest. He stayed in hospital for 8 months. After he left the hospital he was sent to study in the Navy College in Baku. He studied there in 1943-1945.

My mother had a certificate confirming that my brother was a student of the Navy College and it became our permit to leave Odessa for Sevastopol on a military boat along with other families of navy militaries in August 1941. Unfortunately, our grandmother Surah-Leya couldn’t come with us. She was very old and stayed with Zhenia. She died in September 1941. Zhenia went to evacuation. In Sevastopol we lived in the military barracks and had meals at the soldiers’ canteen. I remember there was a lot of bread on the tables and many women took some for later. I thought it was awkward. A few days later we took a train to Rostov. We lived in a village near Rostov for about 3 months. I don’t remember the name of the village. I went to the 10th form at school in this village. The front-line was approaching Rostov and we moved on to Saratov region. In November 1941 my mother and I sailed down the Don River to Kalach-on-the-Don and from there we took a train to Saratov region via Stalingrad. We reached the small town of Krasny Koot (about 1,250 km from Odessa) and moved on to Karpenka village. My mother and I hardly had any luggage and we didn’t have anything to exchange for food. We hardly had anything to eat throughout the whole trip. It’s hard to say what was worse for us: the cold or the hunger. We lived in a house in the village. Our landlady had a daughter and a granddaughter. We all lived in the same room. I remember one of the boys in evacuation calling me “zhydovka”. The locals treated us well. The collective farm helped us with food. We received flour and potatoes. I went to a tractor operator training course in December 1941 to be able to receive rationed food packages. It was easy for me to study. I was good at physics and knew combustion engines so well that I n could even replace our trainer when he was absent. In spring 1942 I worked as thetractor operator of a small wheel tractor. It was hard work for a girl, though. I became a trailer plough operator. My task was to watch the depth of ploughing or harrowing. I had to walk behind the harrow or plough but every now and then I could climb the tractor to rest a bit. I also worked on the fields in the spring and on a farmyard in the winter. My mother was an accounting clerk at the farm.

We lived in Saratov region from November 1941 till June 1943. Then we moved to Kzyl-Orda in Kazakhstan (2,800 km from Odessa) where Zhenia was in evacuation. I entered the university there. I received a stipend and my mother worked at the mill factory. She was a cleaning woman. Our landlady was a Kazakh woman. Her husband was at the front. I finished the preparatory course at the Ukrainian University and was admitted to the Philology Faculty without exams. I finished the 2nd year at the Faculty of Russian literature and language at the Kazakh Pedagogical University. In 1944 the University reevacuated to Kiev. Once I heard our lecturer on the Ukrainian language and literature (she was Ukrainian) saying to someone “I can’t understand why they do not allow lecturers of Jewish nationality to return to Kharkov and Kiev”. But this also applied to students. The rector of the university selected the students that were going back to Ukraine with the university by their last names. Students with Ukrainian or Russian last names had no problems. I didn’t want to go to Kiev anyway. I wanted to return to Odessa.

In summer 1945 my mother and I returned to Odessa. My mother went to work at the confectionery factory. I wanted to continue my studies at the Odessa University as a third-year student, but after I met with the rector of the university I understood that there was no way for me. He didn’t say anything directly, but I understood this between the lines (Editor’s note: the interviewee refers to the fact that she was not accepted because she was Jewish.). I went to the Faculty of Russian literature and language at the Odessa Pedagogical Institute. Manya, the daughter of my mother’s sister Klara, worked as a secretary of the rector of this institute. She helped me with the admission. There were quite a few Jews in this institute. I never discussed with them the subject of my admission and don’t know how they managed to enter.

Our house was destroyed. It was reconstructed later but we didn’t get our apartment back. We lived with Feiga’s daughter Sonia. She had a 3-room apartment and she let my mother and me one room. Sonia, her husband and their daughter lived in another two rooms. There was a big stove for baking bread in the third room. It used to be a bakery before. In the late 1940s Sonia used to lease her apartment to the synagogue for making matsah before Pesach. We moved out of the apartment at such times and stayed at our neighbor’s. My mother and I lived with Sonia for 16 years.

In 1945 my brother was at the war with Japan (20). He served on the L-19 boat at the Far East. After 4 months he was transferred to the L-14 boat and this saved his life. The L-19 sank at the Laperuz strait at the end of the war. There is a monument to this boat in Vladivostok. My brother was a professional military. He served in the Far East until 1961. In 1961 he was transferred to Feodosia in the Crimea. He was deputy commander of a submarine there and retired in the rank of commander.

In 1946 he took a course of training in Leningrad. He met a girl and they got married. His wife Ania, a Russian girl, came from Velikiye Luki, Pskov region, Russia. My mother always treated Ania very nicely and she didn’t mind having a Russian daughter-in-law. They had 5 children: Volodia, born in 1946, Sonia, born in 1948, Olia born in 1949, Sasha, born in 1952 and Tania, the youngest, born in 1956. I visited them in Vladivostok when Tania was born. They all had the typical Jewish family name of Trachtenburg and they had problems with entering higher educational institutions. At that time there was an unspoken restriction and only a certain percentage of Jews were admitted. Olia used to say: “I failed to enter the Crimean University four times due to my Jewish family name”. Finally she managed it and graduated from the Faculty of Biology of the Crimean University. She works at the university in the library now. Sonia studied at the Moscow Plekhanov Institute of Public Economy by correspondence. She got married and lives in Volgograd. Sasha and Volodia finished a course for TV maintenance and repair in Feodosia and worked at the repair shop. Then Volodia worked at the some plant. They didn’t get a higher education. Sasha lives in Sevastopol and I don’t know what he does for a living. We do not see each other that much. Tania entered the Leningrad Medical Institute. She is hygienic doctor and lives in Leningrad. She is the only one of the sisters that married a Jew. Her husband is a musician and teaches at the Music College.

In 1947 upon graduation from the Pedagogical Institute I got a job at the regional scientific library in Odessa – the library of the former Jewish Clerks’ Support Community of Odessa. At the beginning I worked as a librarian in the reading hall. A year later I was promoted to a bibliographer’s position. This was a much more interesting work.

As soon as I went to work I insisted that my mother quit her job. She had hypertension and was growing no younger. I wrote a letter of resignation for her, put it into her pocket and said: “That’s it. You are quitting. I will be the breadwinner from now on”. My mother often went to see my brother and his family in Feodosia. She adored her grandchildren. She told them a lot about the Jewish life that she remembered from her childhood. She taught them to cook traditional Jewish food. Mother remembered all my grandmother’s recipes. When Maya, the daughter of her niece Sonia was getting married, my mother cooked gefilte fish that was enough for all guests. My nieces learned to make gefilte fish from her.

I was so happy to hear about the formation of Jewish state in Palestine in 1948. However, there was practically no information about it in the Soviet newspapers. I can’t say that I felt that I had to live there. My roots are here and my ancestors lived in this land. But I strongly believe that Israel must go on. I do remember a surge of anti-Semitism during the 6-day war in 1967. Once two of my colleagues discussed the subject of Lebanon aloud. The husband of one of the ladies was a navy attaché in Lebanon and she stayed in Lebanon and Syria for some time. She said, “The Israelis destroyed Lebanon.” The second one replied, “If only it were possible to do away with Israel, but they won’t let do it”. I kept silent. If I had spoken my mind then I might have been accused of Zionism and I would have lost my job. It was only possible to discuss such matters with close friends.

I felt such pain about the anti-Semitic campaign of the fight against the cosmopolites (21) in 1950. It was all the more cynical, as it was organized by Stalin in the state that won a victory over the fascists. The books of the leaders of the Jewish anti-fascist committee were removed from the library. They were all outstanding Jewish writers, Peretz Markish (22), Dovid Bergelson (23) and Lev Kvitko (24). They were all shot in 1952. In 1952 the Doctors’ Case (25) was on. It didn’t touch anybody in our family, but I remember meetings in the library where people condemned the doctors for the “murders”. There were rumors in Odessa that all Jews were to be deported to the North or to the Far East (26).

Stalin’s death in 1953 put a sudden end to all these horrors. I yielded to everybody’s mood of sorrow. I wore a black and red band on my sleeve and had a feeling of great concern. People were afraid that things would grow worse. In 1956 Khrushchev (27) spoke on the Party Congress and denounced the cult of Stalin. It wasn’t a shocking experience for me. This was the beginning of the period that was later called a “thaw”.

In 1961 my mother and I received a one-room apartment in Khvorostin Street. We didn’t even have running water. We had water piping installed a year later. The apartment was very damp and my mother had pneumonia several times. She died in 1975. My brother and I buried her at the Jewish cemetery. After she died I received a new one-room apartment with all comforts in the new neighborhood of Tahirov. I never got married. In 1979 I retired, but continued to work part-time at the library until 2001. In 1994 my brother Leonid died. He was buried in Feodosia. I keep in touch with his daughter. I visit my niece Olia in Simferopol every year. Her children Tania and Misha visit me in Odessa.

In the late 1980s at the beginning of perestroika Jewish life in Odessa began to revive. (Editor’s note: The Jewish population of the city is estimated to be about 20, 000 people today. The two synagogues are packed during the holidays but old men pray every day. There are three Jewish schools and kindergartens. There is a regional Jewish Culture Center called Migdal, an Israeli Cultural Center, and the Sochnut and the Joint also have their offices in Odessa.) I enjoy attending all kinds of Jewish activities. I also read Jewish books in Russian translation. The Jewish charity fund the Gmilot Hesed supports me. Every ten days I get food packages from them. I enjoy reading the Jewish newspaper “Or Sameah” and “Shomrei Shabos”. By the way, on 5 November 1997 the newspaper “Or Sameah” published an article dedicated to the 50th anniversary of my work at the library entitled “Just Work or a Unique Record”. They called my 50-year dedication to my job a record.

Glossary

1. Vitebsk: Provincial town in the Russian Empire with 66,000 inhabitants at the end of the 19th century.

2. Tzymes: sweet bean or carrot dish.

3. Nikolay’s army: soldier of the tsarist army during the reign of Nicholas I when the service term was 25 years.

4. Cantonist: younger boys that were trained for service in the tsarist army during the reign of Nikolay I. The institution of cantonists was introduced in 1827 and it became compulsory for Jewish families to allow their sons to serve in the army. As a rule they were children from poor Jewish families.

5. Jewish Pale of Settlement: certain provinces of the Russian Empire were designated areas for permanent Jewish residence and the Jewish population (apart from certain privileged families) was only allowed to live in these areas.

6. Elisavetgrad: town in Kherson province. Since 1924 – Kirovograd, a regional town in Ukraine.

7. to keep in touch with relatives abroad: The authorities could arrest an individual corresponding with his relatives abroad and charge him with espionage, send to concentration camp or even sentence to death.

8. arrested in the end of 1937: In the mid-1930s Stalin launched a major campaign of political terror. The purges, arrests, and deportations to labor camps touched virtually every family. Untold numbers of party, industrial, and military leaders disappeared during the “Great Terror”. Indeed, between 1934 and 1938 two-thirds of the members of the 1934 Central Committee were sentenced and executed

9. International: it was the anthem of the USSR between 1918 and 1943.

10. Gangs: during the civil war in 1918-1920 there were all kinds of gangs in Ukraine. They used political slogans to cover their criminal deeds. These gangs were anti-Soviet and anti-Semitic.

11. Jewish collective farms: such farms were established in Ukraine in the 1930s during the period of collectivization.

12. Moldavanka: poor Jewish neighborhood on the outskirts of Odessa.

13. Odessa: The Jewish community of Odessa was the second biggest Jewish community in Russia. According to the census of 1897 there were 138,935 Jews in Odessa, which was 34,41% of the local population. There were 7 big synagogues and 49 prayer houses in Odessa. There were cheders in 19 prayer houses.

14. famine in Ukraine: In 1920 a forced famine was introduced in Ukraine that caused the death of millions of people. It was arranged in order to suppress the protesting peasants that did not want to join the collective farms. There was another dreadful forced famine in 1930-1934 in Ukraine. The authorities took away the last food products from the farmers. People were dying in the streets, whole villages became deserted. The authorities arranged this specifically to suppress the rebellious farmers that did not want to accept the Soviet power and join the collective farms.

15. Torgsin stores: these shops were created in the 1920s to support commerce with foreigners. One could buy good quality food products and clothing in exchange for gold and antiquities in such shops.

16. Dalnik: village 20 km from Odessa, the place of mass executions of Jews during the war.

18. Komsomol: communist youth organization created by the Communist Party to make sure that the state would be in control of the ideological upbringing and spiritual development of the youth almost until the age of 30.

19. Voroshylov admission: forced assignment of young people to military colleges. This was because many officers were exterminated by Stalin and the army had to replace them.

20. war with Japan: In 1945 the war in Europe was over, but on the Far East Japan was still fighting against the countries of the anti-fascist coalition and China. The USSR declared war on Japan on 8 August 1945 and Japan signed the act of capitulation in September 1945.

21. fight against the cosmopolites: anti-Semitic campaign initiated by Stalin against intellectuals: teachers, doctors and scientists.

22. Peretz Markish (1895-1952), Yiddish writer and poet, arrested and sentenced, rehabilitated posthumously.

23. Dovid Bergelson (1884-1952), Yiddish writer, arrested and sentenced, rehabilitated posthumously.

24. Lev Kvitko (1890-1952), Jewish writer, arrested and sentenced, rehabilitated posthumously.

25. Doctors’ Case - The so-called Doctors’ Case was a set of accusations deliberately forged by Stalin’s government and the KGB against Jewish doctors of the Kremlin hospital charging them with the murder of outstanding Bolsheviks. The “Case” was started in 1952, but was never finished because Stalin died in 1953.

26. deported to the North or to the Far East: In the 1930s Stalin’s government established a Jewish autonomous region in Birobidjan, in a desert with terrible climate in the Far East of Russia. The conditions were very inhospitable there. There was no water, power supply, houses or transportation. The Soviet government hoped that educated people would populate this area and make it a civilized republic. People were in no hurry to leave their jobs and homes and the comforts of living in a town and move to the middle of nowhere. The Soviet government set the term of forced deportation of all Jews to Birobidjan in the middle of the 1950s. But in 1953 Stalin died and the deportation was cancelled.

27. Nikita Khrushchev (1894-1971), Soviet communist leader. After Stalin’s death in 1953, he became first secretary of the Central Committee, in effect the head of the Communist Party of the USSR. In 1956, during the 20th Party Congress, Khrushchev took an unprecedented step and denounced Stalin and his methods. He was deposed as premier and party head in October 1964. In 1966 he was dropped from the party's Central Committee.