Andrei Popper

Arad

Romania

Interviewer: Oana Aioanei

Date of interview: September 2003

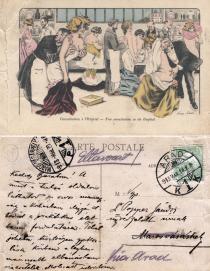

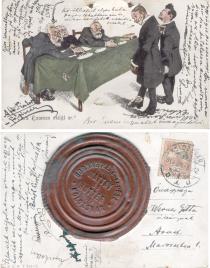

Mr. Andrei Popper lives in an apartment on the banks of the River Mures. Being an elderly man, he spends most of his time indoors: watching TV and reading the newspaper. His living room shelters several pieces of old furniture, while the walls are covered with paintings. One of them was made by his maternal grandfather, while in high school. Two Siamese cats are sprawled out in the armchairs of the entrance hall. Mr. Popper possesses a rich collection of postcards and photographs that he took in various places in the country. He’s a history enthusiast, so he really enjoys telling stories. [Mr. Popper died in August 2004.]

My family background

My mother’s maternal grandfather, Ignatie Pollak, lived in Sebis, where he was in the trade business. His tombstone reads ‘Pollak Ignatie’ and ‘Sebis’ between brackets – the place he came from. I found out from some documents in Sebis that he was one of the leaders of the community there; he had an honorary chair. I think that, at a certain point, he moved from Sebis to Rapsig, because my maternal grandmother, Matilda Pollak, was born in Rapsig, in the Arad County, between 1858 and 1860. Ignatie Pollak bought a house in the center of Arad in 1870. My mother’s maternal grandparents, the Pollaks, were buried in Arad.

My mother’s paternal great-grandparents, the Werners, came from Germany. My maternal grandparents came from a German family; Werner is a German name. One of the Werners fell in love with a Jewish girl and converted to Judaism for her sake. But the girl’s parents chased her away from home, from Germany, and the couple emigrated some time between the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century and settled in Santana, in the Arad County; Santana was a village of Germans. The Werner great-grandparents were buried in Santana. In time, some of the members of the Werner family moved from Santana to Pancota, Beliu or Baia Mare; many of them went to Budapest, where they changed their name to Timar. Great-great-grandfather Jakab Werner was married to Maria Wolf; the two of them had three children, all of whom were born in Santana: Lipot, my great-grandfather [1817-1894], Moric, born in 1823, and Adolf, born in 1831. Adolf had two children: Dr. Miksa Werner, who worked as a physician in Arad, was a bachelor, had no children and died in 1920 in Arad, and Eszter Werner. Eszter married Sandor and the two of them had two children: Artur, who had no children, and Lenke, who married a Krausz and had two children: Anna and Dr. Miklos Krausz, a physician in Cologne [Germany].

Lipot Werner, my great-grandfather, had nine children: Carol, my maternal grandfather, Adolf, Henrik, Simon, Karola, Cili, Imre, Maria and Rozsa. Adolf was the last of the Werners who lived and died in Santana. He was a tradesman and had five children: Mici, who married a Zeisler and had no children, Renee, who married Dr. Wiener and had a son who is a physician in Germany, Pavel, Lajos and Laszlo. Henrik had eight children: Sandor, who had three children: Marta, Bozsi, who in her turn had two daughters, and Viktor, who died in Germany and had a son who worked as a doctor in a military hospital, probably in Cologne, Frida, Regina, Frigyes, who had a son, Alexandru, Ede, Karola, Gyozo and Geza. Simon had four children: Sandor, Jeno, Jozsi and Geza. Karola was married to Samuel Nussbaum. Cili had three children: Lajos, Bela, and Frida. Imre had five children: Roza, who married Adolf Fodor, Maria, who married Dr. Mihaly Deutsch and had a son, Lorant, a PhD in Law, who died in Tel Aviv, Olga, who married Filip Gruner, and Janos. Maria married Adolf Grosz. My grandfather’s youngest sister, Rozsa, married Emil Bauer and had three children: Tuli, Misi and Olga.

My maternal grandfather, Carol Werner, was born in Santana on 15th May 1850. He went to high school in Beius; it was a Greek Catholic high school. I was told that the teachers there were wonderful. A painting he made when he was a student is hanging on one of my bedroom walls. It’s a very beautiful painting: a country house in the middle of the field, a lake in front of it and a boat with two fishermen on the lake’s shore. Everyone says it’s a very valuable painting. My grandmother didn’t know that my grandfather could paint. She only learnt about the existence of the painting after her husband’s death. Grandfather Carol wasn’t a very religious man. I don’t know where he did his military service.

My maternal grandmother, Matilda Pollak, who became a Werner after she got married, was a housewife. She had a brother, Ignatie, and two sisters, who were housewives too: Rozalia and Fani. Ignatie Pollak owned a vineyard in Cuvin. He had two daughters. One of them, Margareta, who married a Szolosi, was a teacher and a high school principal in Arad; she had a daughter, who was a housewife. The other daughter of Ignatie’s, Terezia, married Dr. Venetianer, who was chief rabbi in Budapest. [Lajos Venetianer (1867-1922) became a rabbi in 1892. In 1893, he was in Csurgo, in 1896, he was in Lugoj; he became chief rabbi in Ujpest in 1897. Apart from theological studies, he wrote works on the history of the Jews. He was a professor at the Jewish Theological Seminary-University of Jewish Studies in Budapest and chief rabbi in Budapest.] The two of them had a daughter, Vali Ilona, which was her stage name, who was a very well known actress in Budapest. I don’t think her family had any problem with her being a renowned actress. Rozalia lived in Ghioroc and had a boy and a girl. The boy died when he was a student. The girl, Terezia, who married a Szekely, had a son named Ladislau. Her husband worked as a veterinarian in Glogovat. Ladislau’s son bears the name Ladislau too and works as a physician in Germany. My grandmother’s other sister, Fani Freund, had a boy who died while he was a Law student. Fani became a widow and died in Arad.

Grandfather Carol and Grandmother Matilda lived in Simand. In 1892, they moved to Arad. Grandmother Matilda was in charge of the household; she went to the synagogue for the two great holidays: the New Year and the Day of Atonement. She didn’t keep the kashrut and wasn’t too religious; she did light the candles on Sabbath. My grandfather traded grains and hides. He ran his business in Arad. He had a grain warehouse near his place and a hide warehouse located somewhere else. During World War I, his employees were exempted from military service. In Arad, the Werner grandparents lived in the center of town, in the house that had been bought by my great-grandparents. It was the first house that the Communists demolished. When the nationalization 1 of the houses came, their house was on the list, even though my mother was the rightful owner. This is the house where I was born. I got along well with both my maternal and paternal grandparents. None of them were interested in politics. They were all on good terms with their neighbors. I remember that, after my grandfather died, Uncle Alexandru [Werner] visited my mother every day; he was a pretty renowned dermatologist here in Arad. My maternal grandparents both died in Arad: Grandfather Carol died on 2nd January 1916, and Grandmother Matilda died in 1936, when I was 21.

My mother had several brothers and sisters who were all born in Simand; they were Alexandru, Francisc, Irina, Ivan and Leopoldina. The one I knew best was Uncle Alexandru, born in 1883, who was a physician in Arad and married Ileana Halmagyi. She was a housewife. The two of them had two children: Ana and Gheorghe. Ana died of scarlet fever in 1928, at the age of three or four. Gheorghe graduated from medical school, completed his internship, and came back to Arad. After two years, he caught a disease and died at an early age of 24; he had a daughter, Cristina Gordon, who got married in Cologne. Alexandru died in 1936, before Gheorghe’s decease; I was 22 at the time, and Ileana remarried.

Francisc [1884-1902] died young too. Irina, born in 1887, was a housewife and lived with her husband, Iosif Somogyi, an accountant in Arad. They didn’t have children. Iosif died in 1925, and Irina in 1969. Ivan, born in 1892 died at the age of two, in 1893. He was buried at the Jewish cemetery in Simand. There’s a great cemetery there and the children’s tombs are right at the entrance. The youngest child was Erzsebet-Leopoldina, who was born and died in 1896.

My mother, Margareta Werner, was born in Simand, on 11th April 1890. When she was about two, she moved with her parents to Arad. As there was no high school for girls in Arad at that time, my mother was sent to Timisoara, to the Higher School for Girls. She was a housewife. Just like my father, she wasn’t too religious.

My paternal grandfather was named Carol Popper and was born in Berechiu, in the Arad County, in 1864. He had a brother, Samuila, who lived in Cermei. He also had a sister, but I can’t remember her name. I’m sure he did his military service because he had become a sergeant; I think he served in Vienna [today Austria]. For a while, he lived in Socodor, where he kept a store, but he moved to Arad in 1890, when my father was one or two years old.

My paternal grandmother, Iuliana Popper [nee Werner], was born in Siclau, in the Arad County, in 1867/8. I don’t remember her having any brothers or sisters; she was a housewife. After she got married, she lived in Socodor; after a while, she moved to Arad, where she stayed until she died. My paternal grandparents lived in a one-floor house, opposite the railway station; it was pretty large, but it wasn’t theirs, they paid rent. The place had belonged to a non-Jewish man who had no family. Eventually, he donated it to the Romanian Christian Orthodox Community in Lipova. As my grandfather got to Arad in 1890, he may have rented the house directly from the church. When the block of apartments was built, it was demolished; this happened around 1944 or right after the war. The house had a pretty large courtyard, but it had no garden. My grandparents didn’t breed animals. My grandfather had a rather large store in Arad too. He was a tradesman; he sold all sorts of things and, apart from the store, he also ran a kind of pub. The store, which had been painted by Eugen Popper, a cousin of my father’s, was at the front of the house, while the dwelling space was in the back. My grandfather was widely known among the railway workers; they were his regular customers, since the store and the pub were located opposite from the station.

Neither my grandmother, nor my grandfather was very religious. They were like most of the Jews in Arad. My grandfather wasn’t a devout man, and the Jews in Arad kept their stores open even on Saturdays. However, the New Year and the Day of Atonement were special days. They all closed their businesses and went to the synagogue. On Friday evenings, women would light the candles, but they didn’t usually go to the synagogue to pray. This is how things were in Arad. Grandmother Iuliana died when I was about 18, in 1933. Grandfather Carol died when I was about 20, in 1935.

There was a Neolog 2 community in Arad. The great synagogue was built in 1834. It wasn’t an easy thing to do. Back then, the city didn’t belong to the Hungarians, nor to the Romanians, but to the Serbs. And they prevented any attempt of erecting something permanent. As a result, some representatives of the Jewish Community in Arad went to Vienna and offered the land to the Emperor as a gift. Gendarmes were hired to guard it and the construction could thus be completed. The entrance is through a courtyard, as the synagogue is surrounded by other buildings. Every now and then there’s a concert held there. It has a very good organ. An expert claimed that such a good organ is a rare thing and that moving it would destroy it and so the organ must stay in the building. I read somewhere how it was purchased and set up inside the synagogue: the Jews organized a ball in 1850, and all the intelligentsia of the city were invited, regardless of their faith; the income from that party was used to buy the organ. This information was found by Professor Gluck in the library of the University in Cluj. [Editor’s note: The interviewee is talking about Jeno Gluck who’s a present-day historian in Arad.]

On holidays, the synagogue was overcrowded with people. Until 1940, a summer theater would be rented on holidays; it used to be located on the banks of the River Mures, but it was demolished in 1940, and a service would be held there too. Towards the end of World War I, around 1917, the Jewish Orthodox Community 3 was established in Arad. The Orthodox synagogue was erected in 1921. Its architect was Tabacovici, a Serb who also designed the Roman Catholic cathedral of the Minorites. I met him; he was a great architect.

My father had three sisters and he was the oldest child. Their names were Matilda, Ileana and Irina. They were all housewives. He didn’t have brothers. The oldest of the three sisters, Matilda, married Sigismund Brenner, an accountant. They had two children: Zoltan, who committed suicide around 1969 and had a daughter, Eva, who married Pavel Brenner and left for Israel with him, and Edita, who was married too, lived in Oradea, got deported to Auschwitz [today Poland] and died there. Ileana lived in Arad with her husband, Friederic Fulop, a musician. They didn’t have children. Irina married Samuila Havas, a hide tradesman. They lived in Arad and had a son, Ladislau, who left for Israel, where he was wounded and died in the last day of the War for Independence.

My father, Alexandru Popper, was born on 15th January 1888 in Socodor. He moved with his parents to Arad in 1890. He graduated from the Faculty of Law; he had a PhD in law and worked as a lawyer his entire life. He studied the first two years in Budapest, but he finished in Cluj, in 1908/1909. He entered the faculty in 1905 and he was the youngest among his fellow-students, as he had begun going to elementary school at the age of five; he wanted to be the first to get his PhD. The only places in Hungary where the graduation exam, the most difficult, could be passed were Budapest and Targu Mures. My father passed it in Targu Mures. He wasn’t a very religious man. He did his military service in Arad. He liked to collect stones of various shapes from everywhere he went to; he once brought my mother a heart-shaped stone.

How did my parents meet? Arad wasn’t a very big city. My father was a Law student and my mother had gone to school in Timisoara. I think they met after they came back home. They got married in July 1914. They also had a religious ceremony at the synagogue. The next day after they returned from their honeymoon in Austria, World War I broke out and my father was drafted. He became an officer in the Austro-Hungarian army 4. All my grandfather’s employees had been exempted from their military duties and my father could have enjoyed that status too, but he wouldn’t stay home as long as there was a war going on. He served in the Northern Carpathians, in Poland. He found a stone there, which he sent to my mother; she had a silver plate added to it, with the place and the date: Komarno, 8th September 1914. This is where my father suffered a leg wound; he was sent to Arad after that. Then he went back to the front and became a prisoner of war in September 1914. He was taken to Vladivostok in Siberia, where he stayed for seven years: from 1914 to 1921.

The interesting thing about it was that the prisoners of war received an officer’s salary back then; the Russians actually paid them. When the war ended, they were in the Eastern part of the country, close to the ocean. They were gradually moved to East Siberia. The Americans came to rescue the officers of the Austro-Hungarian army; they took them to an island where there were a lot of children who had been evacuated there. The island was located east from Siberia. My father and the other officers were taken there as laborers. What he had to do was take care of two furnaces lest the fire should go out. They were very well looked after and the food was very good. They even received an honorary diploma from the Red Cross acknowledging their work there. My father spent a year and a half there and came home by boat. In his lawyer’s office, the three credentials hanging on the wall were: his BA degree, his PhD in Law degree and the worker diploma from the Red Cross.

Growing up

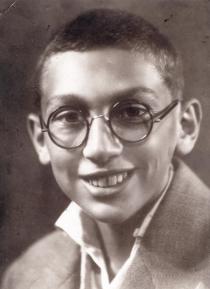

I was born on 29th June 1915 in Arad, in the house of my maternal grandparents. I was my parent’s only child. At the time of my birth, my father was already a prisoner. They would take a photo of me every month and send it to him in Siberia. In the evenings, my mother would pray with me so that God could bring my father home. I first saw him when I was five. He came back from the war in 1921. We lived in Arad until 1923, when we moved to Buteni, I was eight. [Editor’s note: The traveling distance between Arad and Buteni is about 71 kilometers.] But my grandmother continued to live in Arad. Before World War I, my father had a practice in Arad. In 1923, a lawyer passed his Buteni office to an uncle, who in turn gave it to my father. The Buteni courthouse spread its jurisdiction over more than 50 communes [administrative division smaller than a town and comprised of several villages], and the town only had three lawyers; one of them was my father.

Although the county capital was in Sebis, the courthouse was in Buteni; it was the largest building in the entire county. Back in the old days, long before World War I, the Buteni notary persuaded the peasants to send a delegation to Budapest in order to request the opening of a courthouse in Buteni, so that they wouldn’t be forced to go to Sebis anymore. This is how the courthouse was built, some time between 1901 and 1903. The building is still there, but it’s no longer in use, although it’s a wonderful edifice. One night, the county’s prime secretary of the Communist Party had the courthouse moved to Sebis, without notifying the Ministry of Justice. The decision wasn’t altered. But in 1952, when the courts of justice were distributed according to districts 5, the district court house was established in Buteni.

It was in Buteni that Karoly Csemegi ran a lawyer’s practice in the 19th century. He was a Jewish major in the Austro-Hungarian army. After the defeat of the 1848 revolution, he was forced to reside in Arad, where he opened a practice. Because the Austrians persecuted him, he sought refuge in the Romanian commune of Buteni, where he worked as a lawyer for eight or nine years. Csemegi was a very good jurist; he had studied Law in Budapest. After peace was declared between Hungary and Austria in 1870 [Editor’s note: There was no peace treaty in 1870; the interviewee refers to the Great Compromise of 1867.], he was hired by the Ministry of Justice and he ended up as a royal councilor. His greatest achievement was the completion of the Hungarian Penal Code, which is still used today. Until 1946, it was also used in Transylvania 6, up to Gurahont, Zam on the River Mures and to the border of the Bihor County on the River Cris. [Karoly Csemegi (Csongrad, 1826 – Budapest, 1899): criminal lawyer. He was a major in the 1848 war of independence, and because of that he was imprisoned after the war of independence was suppressed. He later worked in Arad as a lawyer, then, from 1867 – the year of the Great Compromise – he entered the Ministry of Justice and later became a secretary of state there.] The Hungarians didn’t have a written civil code, this was only written after World War II, so the Austrian civil code was used in Transylvania. The Romanian one was just a translation: Napoleon’s code was translated into Italian, with mistakes, and from Italian, it was translated into Romanian.

As far as the Jews in Buteni were concerned, I remember one of them was a tradesman, another one was a clock smith; the town’s physician was a Jew, and so was the chief judge, Dr. Erger, accidentally. I remember that during my childhood, there were many peasants who had beautiful handwriting and worked for the courthouse. The Arad County was divided into several electoral districts that counted for the Great National Assembly [the supreme body of the State power], and one of them was Iosasel (today part of Gurahont), which was located between Buteni and Gurahont. [Editor’s note: The traveling distance between Buteni and Gurahont is about 18 kilometers.] Back in those days, Gurahont was nothing compared to Iosasel [Iosas]. The landowner there was a Jew named Polacek. His castle is still there today. Polacek had acquired the estate during the war. He had bought it from the Purglis, an Iosasel-based family who belonged to the nobility, whose daughter became the wife of Horthy 7. I knew the Polaceks: they owned a spirits factory which is still there today. And since we’re talking about the Jewish landowners, I remember that the entire Moneasa and the Dezna Valley belonged to the Wengheims at the time of World War I.

Buteni had a pretty large Jewish community; there were 15 to 20 families. Jews didn’t live separately from the other inhabitants of the town. There used to be a beautiful Neolog synagogue, until 1924/25. It was about that time that many Jews came from Maramures and the Orthodox became the majority group. My father was the president of the community. We didn’t have Talmud-Torah classes; there weren’t too many children. We didn’t learn Ivrit, but we did celebrate our bar mitzvah when we turned 13; the hakham prepared us for the event. We didn’t have a rabbi in Buteni, we only had a hakham. The nearest was Rabbi Sonnenschein in Pancota, in Arad and in Gurahont there was Rabbi Schwartz. After World War I ended, a very powerful Orthodox community was founded in Gurahont; it was larger than the one in Buteni.

The market day in Buteni was Friday; then Wednesday became a market day too, I think. My mother did all the shopping. My family wasn’t very religious. My mother lit the candles on Friday evenings and ate matzah for Pesach. My parents celebrated the New Year, the Day of Atonement and Pesach. But we didn’t eat kosher food, nor did we use separate vessels for Pesach. I remember we had books at home, mainly Hungarian literature. Today’s high levels of crime are mostly due to the fact that, while the parents are at work, the children are left to do whatever they want. In the past, the mother stayed at home and raised the children. My mother always had an aid around the house. All the families used to have an aid back then; moreover, when there was a great clean up or laundry had to be done, more than one aid would be employed. The house in Buteni was rented. We had two to three rooms and running water; the heating was based on firewood.

My parents made sure that I was always well prepared at school. While in Buteni, I took music lessons for a few years, piano and violin, but I didn’t really like it. I also took private lessons in subjects taught at school, especially the foreign languages. In high school, French was taught from the first to the last year; in the second year, we began the study of German, and Latin was introduced in the third year. I think that Ancient Greek was also taught in the sixth year. But I was more interested in Math. My Math teacher was named Stan Crisan. I had friends at school. I also had some Jewish classmates. If I remember correctly, it was the hakham who taught the religion class. I studied the first and second year in Arad, then the third and fourth in Buteni, and then I moved back to Arad. We had classes on Saturdays too. The only day off was Sunday.

While in high school, I lived as a tenant with some strangers, non-Jews, although my grandparents lived in Arad. My parents thought my grandparents spoiled me, so it was only during my last year of high school that I lived with them. I always went home, to Buteni, on vacations: for Christmas and Easter. In the summer, while in Buteni, I would play tennis and go bathing with my friends. I can’t think of any other sport that I may have practiced. I passed the graduation exam in 1935. It was very hard: out of 114 students, only five succeeded. I was one of them.

Before World War I, there used to be several Jewish schools in the county: not just in Arad, but also in Buteni and in Simand, which were pretty important Jewish centers. Buteni had a Jewish elementary school until 1943. Incidentally, before World War I, the headmistress of the Jewish school was named Popper; she was Jewish, but she wasn’t from our family. My father met her son during a visit in Budapest, around 1925, and it was interesting for them both to discover that they shared the same name, they were both lawyers and they both came from Buteni.

There were Legionaries 8 in Buteni in the interwar period. I remember seeing ‘Only speak Romanian’-like posters in stores, but they weren’t a real threat. I didn’t have any problem caused by anti-Semitism. I can’t remember anything important politically that would have happened in my childhood. We would just listen to the radio at home and read the Hungarian newspapers in Arad.

During the war

I graduated from the Faculty of Law; I chose Law because I liked it. I started in Cluj, in 1935. Later, in 1939, as I wanted to gain one year, I moved with several fellow-students and friends to Cernauti [today Ukraine]. Both in Cluj and in Cernauti, there were great professors. The difference was that Cernauti had a preparatory year, then three years of study; this is why we wanted to move there. We graduated there, but we never got to pass our last two exams, for the Russians invaded Bukovina 9, in 1939. [Editor’s note: Russians entered Bukovina in June 1940.]

Roman Law was a real delight. I had a professor in Cluj, Mosoiu, whom it was a real pleasure to listen to. He spoke freely, using no notes. And he always organized his time very well. And there were other professors as well prepared as he was. For instance, during a specialization course in Bucharest, after my graduation, I remember the subject of the Supreme Court being taught very well. But I also came across teachers of another kind. For instance, the German teacher would come to class, write a text on the blackboard and have us memorize it. This is all we did during the entire class. The Latin teacher didn’t explain anything to us either. There were no inspections back then, so teachers did whatever they felt like.

I didn’t serve in the army. When Jews were evacuated from the villages, in 1941 [because of the anti-Jewish laws in Romania] 10, my parents moved back to Arad, where they lived until 1944. Then they returned to Buteni. During the Holocaust, I was sent to forced labor from 1941 till June 1944. First, it was in the Fagaras County, then in the Arad County, at the canal of the vineyards of Arad [Paulis, Ghioroc]. I came home when work was interrupted. I lost several years of my life and I only passed my last exams after the war, in Cluj.

After graduating, in 1944, I started my lawyer’s internship with my father, who took me for about two years. I lived in Buteni until 1946, when I was appointed judge in Arad. Eventually, I became the president of the court between 1952 and 1968. In Arad, I lived with Aunt Irina, in the old house of my maternal grandmother. I was also a court president in Ineu for six years and in Chisineu Cris for ten years. I was never married and I never had any children. My father died at the age of 80, in 1968. My mother died at 92, in 1982, in Arad. They were both buried here in Arad.

After the war

By the time I became a court president in Ineu, there was no synagogue there anymore. In 1945 or 1946, the Federation from Bucharest ordered that all the synagogues from the towns where there were no Jews or very few of them were to be demolished. There may have been one family or two left in Ineu. The synagogue in Cermei wasn’t demolished, but it was bought by the Baptist Community and used as a prayer house. I know that the synagogue in Buteni had to be pulled down too, and the land was sold. The Federation issued such an order because there were no Jews left in these places. Dr. Weissblatt, one of the best dermatologists in Arad, once told me about the time when many workers from the furniture factory in Pancota, a very large facility, had caught a skin disease. He was sent there as an official delegate. While in Pancota, he learnt that a worker who had taken part in the demolition of the synagogue had fallen down from the building and died. The whole village found that incident to be pretty natural, since what they were pulling down was a church.

The synagogues in Chisineu Cris and in Seleus were demolished too. I was once at the town hall in Seleus and the mayor showed me the furniture of the place: it had been bought before the destruction of the synagogue, and the mayor’s chair was the old rabbi’s chair. The synagogues in Arad and Salonta are, to my knowledge, the only ones that survived in the entire Arad County. But I heard a few years ago that the synagogue in Salonta no longer exists either.

How come I didn’t immigrate to Israel? I was born in Arad, I lived in the Arad County all the time, and I happened to be appointed as a judge in Arad too. I don’t think too highly of the people who move too much. I believe that, once you start working in a certain place, it’s best to stay there till you die. Under the communist regime, I was still a lawyer; I was a judge president until 1975. When I turned 60, I applied for retirement.

I became a party member against my will. A friend of mine, Ladislau Lakatos, a druggist in Buteni, had gone to college in Bucharest before the war. There he joined a group of communist students and became a fervent Communist too, although he came from a family belonging to the Hungarian nobility. After 23rd August 1944 11, he joined the Party and signed me in too, without asking me about it. I took part in activities organized by the Communists and I had to attend weekly meetings. However, I didn’t become a party member out of conviction, but because Ladislau and me were very good friends. He was a good chap, a true gentleman.

I knew other people who had been accepted in the Party despite their origin. There used to be a bank in Arad; it was called Goldschmidt and it was owned by a Jew. His son, much older than me, studied Economics in Paris [France] before World War I. Back then, one couldn’t study this in Romania, but only in Vienna or Paris. While in Paris, he joined a communist society and became a fervent Communist, although his father owned a bank. When the Communists came to power in Romania, he received a high office in a ministry and was even sent to Hungary as a diplomat, for he spoke Hungarian.

I never had any problems with the Communists. I only met very few of them who liked to cause trouble. The county’s prime secretary of the Communist Party was the only one who had the right to check on me, but he never interfered with what I was doing. This was the order from Bucharest. My coworkers were nice people; as for the clerks I worked with, I was lucky because they did their jobs well. I also had Jewish coworkers: Livia Halmos, Maxim Goroneanu, Ladislau Samuel.

I only went to Israel once, in 1968. I was left with a good impression. I went to a niece of mine, Eva Brenner, right during Pesach. My niece is married to a Romanian from a place in Tara Motilor, near Baia de Cris. His name is Pavel and he’s a very decent man. He wanted to move to Israel and persuaded her to do that. Pavel worked as a locksmith in a factory; Eva is a clerk. They are doing well. I stayed with them for a month and they drove me every day to see as many places as possible. Each day, I visited a new town and some new places. I also went to the USSR, a two-week trip across the Black Sea, to Riga and to the North Sea.

The revolution of 1989 12 had no effect on me. I think nothing has changed. I had already retired when it came. After my retirement in 1975, a friend of mine who worked as the chief secretary of the County Council called me to do voluntary work for his office for a couple of years. Then the Jewish Community called me, and I went to help them with their legal matters. I stayed with them for 23 years, from 1977 until 2000 or so, when I became ill and had to go to surgery. I used to go out for a walk when I felt better. But now I’m too tired to do anything at all; I just read my newspapers at home.

Glossary