Alfred Liberman

Kiev

Ukraine

Interviewer: Roman Linchevskiy

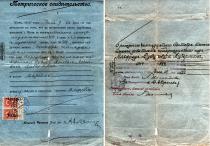

I was born in Kiev on September 30, 1914, one month after the beginning of the First World War, and here I have lived almost all my life, with the exception of the years of evacuation during the Second World War.

My father – David Grigoryevich Liberman (Duvid Gershovich on his birth certificate) was born in 1885 in the small town of Sudilkov, Podolia [southwestern part of Ukraine]. My mother, Maria (Mariam) Isaacovna, nee Berlatskaya, came from Nikolayev, a big city in the south of Ukraine. She was six years younger than my father.

The parents of both my mother and father were born in the beginning of the 1860s.

Early in the 20th century, before moving to Kiev, my father’s parents lived in Sudilkov. Before the October Revolution [1917] Gersh (Grigory) Lazarevich Liberman traded in wood . I think he was successful, because he was able to provide for higher education for all of his children: three sons – the eldest, German, then my father, who became a lawyer, and the youngest, Yevsey, who was a famous economist in 1960s – as well as to his daughter Vera, who became a gynecologist.

I don’t know how religious grandfather Gersh was. I remember they spoke only Russian at his house; I never heard Yiddish there. I don’t know whether he went to the synagogue or celebrated Jewish holidays. He never gathered his family together on Passover or Purim, as is the custom in other families; grandmother never gave us matzos. I think they adopted a secular lifestyle and raised their children in the same spirit.

I remember grandfather Gersh and grandmother Serel. After the Revolution grandfather no longer worked. When we would go to visit them, we had to take a cab from one end of the city and go along one of the most beautiful and longest streets of Kiev – Vladimirskaya – to the other end of the city. It’s hard for me to say now how my grandparents earned their living at that time: it was considered dangerous to ask questions or reveal too much.

I can’t tell you much else about my father’s parents: even though they lived in Kiev, their house was far from ours, and we lived with my mother’s parents. When my grandfather Gersh died in 1924, I was not even ten years old. My grandmother, Serel Grigoryevna, nee Buchman, died five or six years later.

There is a picture of the three brothers Liberman and me when I was 13. Maybe my uncles came to Kiev to celebrate the coming of age of their nephew? [According to the Jewish tradition, a Jewish boy comes of age at the age of 13, and this day is called his bar-mitzvah].

Uncle German was born in 1875. I can say that he followed in the footsteps of his father – forestry economy. He moved from place to place; he worked both in the north of Russia and in the west of Ukraine. There was some sort of instability in his nature.

I will tell you later about my uncle Yevsey, who was a famous economist-reformist in the 1960s, and about my beloved aunt Vera, who lived in Kiev like our family.

Our family lived together with my mother’s parents – Isaac Petrovich Berlatsky and Yulia Moiseyevna Berlatskaya, nee Knebelman. We lived in apt. 17, at 3, Mikhailovsky Lane. We had four rooms: my father’s office, my parents’ bedroom, the children’s room and my grandparents’ room, which later became a living-room.

Grandfather Isaac attended a small synagogue on our street.[It was later closed. Of our more than 300 synagogues in Kiev, only one functioned after the war]. Out of respect for grandfather, who was the only deeply religious person in the family, the whole family kept all the Jewish traditions. Grandfather had sacred books and prayer books in Hebrew. He prayed on his own, standing alone in a corner. Grandmother Yulia, by the way, never attended synagogue and never prayed at home; only grandfather did.

By the way, do you know that in Jewish families Jewish baby boys had a special ritual circumcision a few days after they were born? This ceremony is called “brith”. When I had that operation, uncle Yevsey held me in his hands. I think my parents had this ceremony done for the sake of Grandfather Isaac.

When Grandfather Isaac was still alive we usually celebrated the Jewish holiday of Passover. We got ready for this holiday by cleaning the flat and getting a supply of matzo. Matzo was made in Podol (a district of Kiev), on Schekavitskaya Street. I think it was made at the synagogue. Religious Jews could not eat bread during the period of this holiday, so they ate matzo.

When I was 13 years old, I had a bar mitzvah according to all the rules. Grandfather wrote four Hebrew lines in Russian letters for me to recite at the ceremony, because I had absolutely no knowledge of Hebrew. I learned the lines by heart and forgot them as soon as the ceremony was over. Immediately after the ceremony I ran to my regular school. We were ashamed of following Jewish traditions.

Russian was the dominant language in the families of both my grandparents. My father and mother spoke only Russian to each other and me; they had absolutely no accent. I myself know neither Yiddish nor Hebrew, and I regret this very much.

Grandfather Isaac traded in grain in Nikolayev, in the south of Ukraine. He jokingly called himself “the first exporter” of grain. Eventually, grandfather became an honorary citizen of that city. I think he had to be a 1st Guild Merchant to have that honor. I don’t know what education he had. When his friends came to see him on holidays, I heard them speaking in Yiddish. Sometimes I heard my grandmother Yulia speaking Yiddish to grandfather. Grandmother could write in Yiddish, but I never saw her reading in Yiddish, though I saw her reading in Russian many times.

Grandfather died at the age of 70 from uremia. I don’t remember the exact date of his death. I will tell about the death of grandmother later – she died in the beginning of the Second World War.

Besides my mother, Grandfather Isaac and Grandmother Yulia had another daughter, Sofia Isaacovna, mother’s sister. She married a man whose last name was Byalik, but I don’t remember his first name. They lived in the town of Belaya Tserkov. Her husband had a private medical practice. He was a good doctor. There were only four doctors in that whole town, and he was one of them. Sofia Isaacovna did not work outside the house; she was a housewife. I’m sure she had a housemaid. She survived the war in evacuation. Sofia Isaacovna died at the age of around 75. She is buried at the Baikovsky cemetery in Kiev. Sofia Isaacovna had a son, who was PhD. in medicine. During the war he was a colonel and the chief doctor of one of the fronts. I know almost nothing about his fate after the war.

All the women in our families – my two grandmothers and my mother – were housewives. My grandmothers got their education just like every other woman in Jewish families – at home. I don’t know any specific details about it. My mother finished seven grades of school. She liked music very much and often attended concerts at the philharmonic society and the Opera Theater. My mother was a housewife, but we always had a housemaid. My mother did not bother do much around the house even when , for a short time, we had to rent out one room due to financial needs.

My father, David Liberman, got a law degree from Kiev University. Before the October Revolution he worked as an assistant attorney (I think Jews were not allowed to become full-fledged attorneys at that time). After the Revolution, he was a member of the Kiev Bar and worked as a legal consultant in Soviet municipal establishments and consulted private enterprises [this could be so only in 1920s-beginning of 1930s, because later all private business was closed down and then, soon after the war, eliminated].

My father’s main place of work was the Ukrainian Red Cross organization. He was a legal consultant to the central committee of this public organization. The Red Cross had branches at every enterprise and every school. Newspapers wrote a lot about the charity activities of the International Red Cross organization, and because of this I always considered my father’s job significant. [In reality, the Soviet authorities used this organization as a good screen in front of the international public].

Neither my father nor mother was religious. In our family we celebrated Jewish holidays only when grandfather Isaac was still alive. After his death we stopped. Neither of my parents went to synagogue or prayed at home. Naturally, I was absolutely indifferent to any religion.

Most of my parents’ friends were Jewish, but all of them were assimilated. Most of their friends were my father’s colleagues.

Our family was so prosperous that my parents could afford to hire a French tutor for me, their only son. I still remember the poems and proverbs that she taught me. I am fluent in reading French even now, although I am not so good at speaking it due to a lack of practice: my French tutor moved out of Russia immediately after the Revolution because of “those barbarians,” as she called the new power.

Then I had a nursery governess, who cared for a group of children all about the same age. I can not remember the names of the children or the governess now. She went for a walk with children from our area. All of us had approximately the same level of knowledge and education. She spent all morning outside with us, then we went over to her house, had breakfast and some of the children even went to bed.

All the children were certainly from prosperous families. The governess taught me to read and write and with this, I could enter the third grade of United Labor School # 79 at once, skipping the first two forms.

The teaching in this school was in Russian. I could certainly have gone to a Jewish school – it was not a problem in 1920s, but my parents saw no sense in it. We had 25 students at our class, and the class was mixed – both boys and girls. The main language of Russian; only a few students spoke Ukrainian. Kiev was a Russian-speaking city at that time. We had good teachers at our school, for instance, the future president of the Academy of Sciences, the famous Academician Alexandrov taught physics. We also learned German. It was the main foreign language taught at schools at that time. There were many Jews among teachers and students alike, but there were no tensions between us. We, Jews, always knew who was a Jew and who wasn’t. This was something we felt subconsciously. Besides, Jews had a Jewish appearance and surname, this distinguished them from the others. Later, when I studied at the technical college and institute, it did not matter whether I was Jewish or not. At school we certainly had pioneers,1. but I didn’t join the pioneers or Komsomol. At that time it was not yet mandatory; they selected only those who were “worthy” and did not allow those who came from “non-proletarian” families.

I began to grasp the full meaning of having a “non-proletarian” origin only later, when after seventh grade I wanted to enter the construction technical college and after that, university. Back at school I had decided that I wanted to become a construction engineer, but due to the fact that my father was a “specialist” [that is, a specialist with a university degree who was an office worker], I could not enroll in the construction department. Things were very difficult, because the Soviet authorities at that time recommended that all institutions give educational priority to the children of workers and peasants – and my father was a lawyer. I could only enter a self-supporting school, so I enrolled in the textile technical college that was located at Podvalna Street [today’s Yaroslavov Val Street]. I even remember the number of the building – #25. All students of this college had to pay for their education. As far as I remember, our tuition was 25 or 30 rubles a month, which was a lot. There I met the son of a merchant, the future Academician Boris Israelevich Medovar. I knew him very well. But I did not finish my studies at that college, because I enrolled there only out of necessity. My goal remained to be a builder.

In order to open the way for me to go to the right school, my father took special courses and became what was called a “technical specialist.” The Soviet authorities had much more respect for “technical specialists” than for simply “specialists.” Children of “technical specialists” had a chance to enter university. But I also had to have a proletarian job to do so. So I spent almost half a year working as a stamp operator in a workshop. I was around 15 years old then. My job was to make metal rivets for knives with wooden handles – the handles got attached to the knives with my rivets. I worked there for four months. Since I was qualified to enter the university in every other way, I asked for a certificate that said that I was a worker. Now I had a “technical” father and my own “proletarian” experience, tiny though it was.

This helped me enter the Kiev Institute of Construction Engineers in 1932. I also got some help from the Institute’s legal consultant, Isaac Grigoryevich Bek, who was an acquaintance of my father. But I took the entrance exams just like everybody else.

I have wonderful memories of my Institute. The standards of both teachers and students were high. One of our foremost teachers was Nikolay Vasilyevich Karnaukhov, a Corresponding Member of the Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. He always treated us with respect. Most of us (23 out of 26) were Jewish. We had absolutely no “national” problems with other teachers or students. I graduated from the Institute with honors and was given the diploma of a construction engineer. I remember my student years for other things too. Even though we spent a lot of time studying, we still had time for fun. We were young. We dated girls, watched movies, went to theaters. I took classes at a dance school. The head of this school was called Berdichevsky. I think he was an opera actor. Learning dances was fashionable then: tango, blues, Boston. There was another dance school led by an engineer-economist named Miller. He taught dancing for material reasons because it paid well. He had groups of people who paid him for teaching them dancing. He rented a club and our students went there. Some took dance classes from both teachers. Sometimes students drank alcohol, but they never got drunk. In general, youth is youth....

During my student years I did not face any national problems, but I faced other problems whose meaning was hard for my generation to evaluate. In autumn 1932 an unheard-of famine began in Ukraine. [This famine took a toll of 5-6 million lives. All the harvest was confiscated from peasants, and the Ukrainian rural residents started dying out. Peasants stole into cities for bread, bypassing military guards.] In the streets of Kiev I saw weak, skeletal people who stood in long lines for bread. Every morning street cleaners would take away dead bodies.

I remember one case when I was summoned to the Komsomol committee of the Institute, even though I was not a member of the Komsomol. I didn’t even talk much to them, not because I didn’t want to, but because I had no time. I was mostly interested in studies. Komsomol was afraid of the Mensheviks, and they considered my father to be a Menshevik. Anyway, they summoned me and gave me an order – to take a sack of bread to the village of Brovary outside Kiev. There was a special collective farm there that our Institute was in charge of [an organization half ruled by the state; peasants were forced to join such collective farms with everything they owned (to be collectivized), while many urban organizations were “in charge” of such farms, helping them with machinery and manpower.] Students of our Institute were working at that farm. I was given a large sack of grain, but I asked them to give me something smaller because I was not very strong physically. I remember vividly how I left the Komsomol committee with the sack. I don’t remember exactly how I got to the farm – probably by electric train. Our students were starving there just like everyone else. So I gave the sack to those at the farm who were still alive. I remember a street in this village – there was nobody outside and all the windows and doors of houses were closed.

When I arrived at the farm I, too, had to work there for two or three weeks. We stayed in the school and slept on the floor, I think on mats. Then every year we were sent to collective farms to do different kinds of work.

Physically I was rather weak; I never even did any physical exercise. I had no time for it. But I remember we would be sent to work at a collective farm for three weeks or a month. And I had to do the most difficult physical work: I had to stand on top of a threshing machine and put sheaves into the threshing machine to be threshed. It was a very hard work. I still remember how dust got into my eyes and I had to lift up those heavy sheaves and put them down and repeat this action an endless number of times… I asked my chief to transfer me to an easier work in the village. He allowed me to put sheaves on carts. The sheaves lay around everywhere. I had to pitchfork them and put on the carts. When the cart got full, it went to take the sheaves to the threshing machine, and I had time to rest. I worked this way for three weeks. We were fed three times a day. I don’t remember exactly what we ate, but I remember we had bread. For lunch we had a very liquid soup, porridge and bread. We also had about a one-hour-long break. In the afternoon and evening we worked again and when it got dark we returned to the school we stayed at. Practically nobody else worked in the village, because many people had starved to death and many moved to cities to find jobs there. Dead bodies lay around at the Brovary train station. These people had died of starvation. We were usually sent to agricultural works in autumn, in September, because a lot of seeds were sown, but very few people were left to gather the harvest – those who were strong enough moved to the city, while those who remained were too weak to work.

It is terrible to think of the years 1932-1933. There was famine all over Ukraine. People ate horse-flesh. I remember when I returned home from the farm, my father told me, “Horse’s flesh is very red.” Every time I see horses now I think of their flesh. Well, my father had a job, and it was easier to get foods in the city, so we ourselves did not really starve.

I learned about the real scale of the “mistakes” of collectivization only in early 1990s, when the famous [1986] book by Robert Conquest, The Harvest of Sorrow, was translated into Russian. Conquest wrote another book on the pre-war USSR – The Great Terror – about the mass repressions that affected millions and millions of people.

Our family also suffered. My father was arrested twice. Unfortunately, I hardly know any details about this, as father did not like to talk about it. I was also afraid to ask, all the more so because it all ended well for our family. This was after the end of NEP2 in 1934. Many businesses opened under NEP, and my father consulted some of them as a legal consultant. In the late 1920s-early 1930s, the authorities began to close down free commerce in the city. At one point, they came to arrest my father. We were shocked. Later, he was released (maybe he was released due to the fact that we appealed to the prosecutor – an old Jewish Bolshevik with great revolutionary party experience. Many in the power structure realized the absurdity of what was going on but could help only in rare cases).

My father’s brother – Yevsey Grigoryevich Liberman – was also among those arrested at that time. He was born in 1897 and graduated from Kiev University. From 1923 he worked in Kharkov. He was an undoubtedly talented man: he later created an economic school famous all over the country. He started in Kharkov [which was the capital of Ukraine then] as an assistant or a secretary to a famous party leader of the Ukrainian Republic, People’s Education Commissar Nikolay Skrypnik. When Ukraine suffered famine and they began arresting the national Ukrainian intelligentsia, Skrypnik, as one of the honest people of the old generation of party members, committed suicide. So, when my uncle, then a young economist, was arrested, working for Skrypnik was one of the charges against him; he was accused of supporting Ukrainian nationalism (they apparently forgot that he was Jewish). He was imprisoned for almost a year. He was even tortured. But he did not sign any papers. One of my uncle’s students, who was teaching at the Kharkov Economic Institute at the time, helped obtain his release. Later, this student became the leader of the city party organization.

People tried to hush up the truth about the arrests. The extent of people’s fear can be seen from the following episode. Uncle Yevsey and his wife Regina Gorovits [the sister of the world’s famous pianist Vladimir Gorivits, who lived in the USA], was visited by the Vladimir Gorovits’ wife, V. Toscanini.

My uncle thought it was necessary to ask the NKVD [People’s Commissariat of the Interior] for permission to receive this foreign guest. He also asked them to send a representative of the authorities to every family meeting with her. It was probably due to the fact that his sister-in-law was known worldwide (she was a daughter of the famous conductor Arturo Toscanini), that there were no negative consequences for the Liberman-Gorovits family for having had “contacts with foreigners,” even though in many other cases it was enough for someone to have a relative abroad in order to be arrested and disappear.

Later, my Uncle Yevsey’s lectures, articles and speeches drew the attention of the highest Soviet leadership; he won support from prime ministers Khrushchev and then Kosygin. An article titled “Plan, Profit, Prize” that he published in “Pravda” [the main newspaper of the USSR] in 1962 touched off a whole discussion among economists, while his line of reforms, supported by the leadership of the USSR, was nicknamed “Libermanization” in the West. The journalist Mark Geiler called my uncle a “leader” in the new Soviet economy and devoted a big article with photos of his meeting with Yevsey Liberman in his flat in Kharkov. This article was published in the French «Paris Match» magazine (March 1966).

My famous uncle died in 1984. Many economists say today that the basis for the liberalization of the economy in 1990s was missing the input of Yevsey Liberman – the “father of the reforms” of the 1960s and the head of the Kharkov school of economists. I felt I had to tell you about the Kharkov branch of the Liberman family.

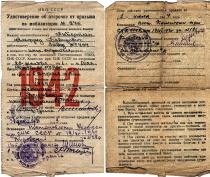

I began to work as a builder in the last years of my university studies. At first, I taught construction design in the River Technical College in Kiev. I also worked as a construction engineer and a designer at the Stalin Shipbuilding Works. And when the Second World War broke out, I was sent to the design organization of the Kiev military district. Because of this, I was exempt from the draft. In August 1941 I was transferred to work on the construction of military objects – plants and aerodromes at the Volga defenses (in the towns of Ulyanovsk, Saratov, Kuibyshev, etc.).

My parents were evacuated with just two suitcases, first to the town of Gorky, where our relatives lived. Later they moved to the town of Buzuluk, in the Chkalov (now Orenburg) region. My father worked in the rear in different organizations as a legal consultant.

Through some relatives I found out where my parents were staying and we kept up a correspondence. In one of my letters I sent them a photo, on the back of which I wrote: “To my dear parents from your son. Saratov, 5. VII. 42” You can still read the inscription. Later, I was even able to visit my parents: we had to build antiaircraft defense fortifications in Buzuluk .

To our deep sorrow, grandmother Yulia, my mother’s mother, could not be evacuated due to her old age (she was 81) and poor health. So she was killed, but not in Babi Yar, like most of the Kiev Jews. She was shot in September 1941 along with a group of other elderly, sick Jews in the center of the city, in the building at Bogdan Khmelnytsky Square. According to our neighbors, it was our street-cleaner Petr who put four old women who could not walk (my grandmother, two Polsky sisters and Mrs. Alexandrova) on a cart and took them to that building, which was a courthouse before the Revolution.

My parents returned from evacuation to devastated Kiev in 1944. In 1946, my mother, Maria Isaacovna Liberman, died, and two years later my father, David Grigoryevich Liberman, died, too.

My aunt Vera Grigoryevna was a lovely person. She was born in 1890 in the town of Sudilkov. Her teacher at the Kiev Medical Institute was the then famous Professor Pisemsky. She worked as a gynecologist in Kiev and during the war worked in the Urals. She got married a year before the war. To the great surprise of our secular family, Vera’s wedding ceremony was traditionally Jewish, with a rabbi, chupah [a canopy put over the bride and a groom during the wedding ceremony], and freilachs [a Jewish folk dance]. Vera’s husband died in the first months of the Second World War.

Aunt Vera’s death was tragic and absurd – she fell down in her own flat after getting entangled in the flap of her bathrobe; she broke her femor, and died some time later from her injury. I don’t remember the exact date of her death.

I got married at the end of 1944 in Kiev, which had just been liberated. I returned from evacuation together with my parents and my bride – Frida Isaacovna Khatset. We met in Buzuluk ,the town where my parents stayed during evacuation; Frida was working at a military plant. My wife’s parents were very good, wonderful people. They received me very warmly and made friends with my mother. They were born into very poor Jewish families, in Kiev. My wife’s parents were religious, kept all traditions, and went to synagogue. But Frida, like me, was a Soviet child.... My wife is five years younger than I am; she was born in 1919. Right before the war she graduated from the chemical department of the Kiev University.

In 1946 our son Georgy was born. After the war, Frida Isaacovna worked as a researcher at one of the institutions of the Academy of Sciences. When she was left jobless in 1952, at the peak of Stalin’s anti-Semitic repressions, she used her “idle time” to great benefit: she wrote her Ph.D. thesis. But it was only with great difficulty that she was able to defend her thesis, and it was only after the anti-Semitic wave had passed and she could return to work in her research institute.

In 1948 I defended my own Ph.D. thesis and began lecturing at the Kiev Road-Transport Institute. However, a year later I had to quit that job due to “failure in fair competition.” This was the official version behind my dismissal. But I felt that there was another reason. I think the institutions of the Education Ministry and the Academy of Sciences were more “ideology-proven” institutions than industrial bodies.

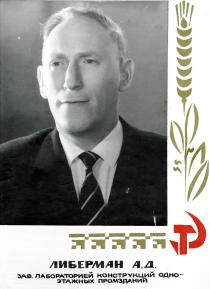

In 1949 I began to work in the Building Construction Research Institute, which was subject to the USSR and Ukrainian Republic’s ministries for housing and industrial construction. There I worked until 1999 – 50 years! First I was a senior researcher, then the chief of a laboratory. Here, in 1967, together with my colleagues, I was awarded the State Prize of the USSR, which was the second main prize of the Soviet Union after the Lenin Prize. You may find it interesting that the group of 11 winners of that prize consisted of five Jews, for instance, Abram Leonidovich Levansky, deputy minister of the electro-technical industry, and Vladimir Pinchusovich Abovsky and Girt Meyerovich Shagal – leaders of the major construction trusts of Siberia.

As far as anti-Semitism is concerned, I would say the management of industrial, productive establishments approached their personnel with pragmatic rather than ideological motivations. In our institute, my Jewish colleagues and I felt no open anti-Semitic attitudes. But somewhere at the top, I heard, it had its effects. For instance, even though I was already a major expert in my field and had been awarded the State Prize (which was called the Stalin Prize until the 20th Party Congress) I was not allowed to travel abroad. My director told me that every time the institute put my name on the list of a delegation to be sent abroad, somebody in the ministry or even higher – in the party bodies – would delete it. It was taken naturally back then. Still, I worked well and was highly respected – and this made me happy.

I should also say that after getting the State Prize, I was asked to join the Communist Party. But I said I was not mature enough. I was asked a second time, and after I gave the same answer I wasn’t approached again.

Something else about anti-Semitism. I was a propagandist in 1952, meaning that during the electoral campaign I had to go from flat to flat (everyone who had a university education was used as a propagandist, not only party members). In doing so, I saw that many “ordinary people” believed the Soviet propaganda and were against the Jews. They were truly afraid to go to Jewish doctors, for example. It was a general attitude. But in our institute, where I worked, anti-Semitism was not overpowering – people’s merit in doing their jobs meant much more.

My son Georgy graduated from the same Construction Institute as I did and has the same profession as I do. First I helped him and we did some work together, but then he would help me when I had problems working.

My son is married. His wife is Russian. In 1970 their daughter Yelena was born.

I retired on a pension in 1999, when I was more than 85 years old. Even after my retirement people continue to turn to me for consultations and references – both my former colleagues and those who read my publications. I have published more than 200 articles and hold a lot of invention patents, etc. People are judged by their deeds.

Only lately have I begun to read Jewish newspapers. I pass on the most important things to my son. I also watch Jewish TV programs. We are also often invited to “Khesed,” and I use its library. We also subscribe to Ukrainian and Russian newspapers. I do my best to follow the news, listen to the Voice of America and BBC. But we certainly spend more and more time on medical problems now.

Regrettably, we at all do not know Jewish traditions, do not know how to celebrate Jewish holidays, do not know Yiddish. Our parents did not teach us this; it was not accepted and not fashionable. It hurts that this is the way things are, but at this point, it’s impossible to change.

We get frequent phone calls from our friends and acquaintances, and we call them. It is hard to go see anyone. My son and his family and some younger friends come to see us.

Among my friends are both Jews and Gentiles with whom we studied or worked. We don’t feel alienated. For instance, we have good friends from the pre-war times, our former neighbors – the Shanin family. In evacuation we worked and lived together. They are Russians. But our closest friends are still Jews. It just happened this way.

I observe with interest life in Israel and other countries, where my friends live - but I think that a person must die in the country to which was born. And that it’s possible to live a full life only at home.