Alexander Ugolev

St. Petersburg

Russia

Interviewer: Nadezhda Lipovskaya

Date of interview: September 2004

Alexander Efimovich Ugolev is a grayish-haired person, not tall and heavily-built. He dresses with negligent grace and elegance: a dapper shirt and carefully ironed trousers. He walks slowly, using a walking stick. He lives in a small two-room apartment with his wife and adult son (a student). His room is very tidy; everything is put in its place with love – to please the owner. The window of Alexander’s room looks to the south. The room is warm and light. The furniture is very simple and comfortable: a large writing-table, a spacious bookcase, full of books up to the top, a soft sofa situated opposite the bookcase. Alexander Efimovich is a deliberate and interesting story-teller. His narration is thick-sown with geographical information and historical digressions. Sometimes he is rigid and hot-tempered in judgments and comments. Being carried along by his memories, he gives way to his feelings and immerses his interlocutor in an atmosphere of a past age.

My kin of the Ugolevs–Tsypkins came from Belarus. Probably all my ancestors are from there. Before the [Russian] Revolution [of 1917] 1 Jews were permitted to live only within the Jewish pale [of settlement] 2: on well-marked territory. There were settlements in Belarus, Ukraine, and somewhere else. But I guess that all my ancestors came from Belarus.

The Tsypkins, the parents of my mum, lived in Krichev [a city on the Sozh River in the east part of Belarus]. I don’t remember the name of my maternal grandmother. She wasn’t tall, even small. The Tsypkins had a farm, even a cow. My maternal grandfather’s name was Haim Ayzikovich Tsypkin. As a child I spent every summer in Krichev at my grandmother and grandfather’s [the Tsypkins]. Abram Berkovich Ugolev and Haya-Ghita Israilevna, my paternal grandfather and grandmother, lived near them, in the village of Komarovka. When Abram Berkovich died in 1941, my grandmother moved from one daughter to another as a prize. She loved me. Both my grandmothers were very nice.

Both grandfathers of mine were Jews in the full sense of the word: they went to the synagogue, prayed at home, put on tefilin, and wrapped small leather strap [tefillin] around their hands. My grandmothers and grandfathers were religious. In order to prepare a chicken, my grandfather Haim Tsypkin took it to a shochet. Grandfather Haim took my hand, we went across Krichev and carried a hen to the shochet. The shochet did his part, and then stroked my head. In Komarovka the Ugolevs – my grandfather and grandmother – observed the kashrut strictly, and in Krichev, where the Tsypkins lived in the 1920s it was difficult, because in the town there were a lot of Soviet officials who kept a vigilant watch on every citizen.

Both grandfathers were patriarchal and hard-working. Haim Tsypkin was a small shop-keeper, and Abram Ugolev was a smith. At home my grandfathers and grandmothers spoke Yiddish. Both grandfathers were bearded, but wore regular clothes.They prayed regularly, at set hours. My grandmothers didn’t wear wigs, they didn’t cover their gray hair. They were dressed in long skirts with elastic webbings and jackets with long sleeves. Grandfather Abram had a large house in Komarovka. In Krichev Grandfather Haim also had a house: two rooms and a kitchen. Both houses in Komarovka and in Krichev were heated by furnaces. In Krichev the furniture was old-fashioned. I remember a large bed. Both in Krichev and in Komarovka my grandfathers had vegetable gardens. Grandfathers worked in vegetable gardens rarely: for the most part women did it. We, the children, were not forced to work in the vegetable garden. In Krichev there was a cow and hens. In Komarovka they kept cattle, too. My grandfathers and grandmothers had no farm hands: they were poor Jews.

Probably, my grandfathers had their own opinions on the political situation in Soviet Russia, but they made no comments. They lived like other people, worked, and affiliated with no parties and societies.

I don’t remember the neighbors of my grandfathers and grandmothers. It seems to me that both in Krichev and in Komarovka people lived in their own separate houses. I think they had good relations.

Usually, after staying in Krichev for several months I easily started to speak and even think in Yiddish. Almost all neighbors were Jews. They dressed the same way as my grandfathers and grandmothers, and men wore beards. I think their lifestyle was Jewish, traditional.

I keep a few bright memories about that time. I remember myself in Krichev pilfering hay from a passing cart just for kicks. The driver noticed it. Well, I caught it from him! All children liked to do it with hay. Well, how can you keep from getting a tag of hay for your cow! Everyone pilfered, and so did I, following their example. I had friends among the boys in Krichev, we went together to the Sozh river for swimming.

I know nothing about the brothers and sisters of my grandfathers and grandmothers. But, probably, my grandfathers sometimes visited their relatives.

My grandfathers and grandmothers didn’t tell me anything about their childhood and I was silly enough not to ask them about it. At that time I wasn’t interested in it, though my grandparents didn’t keep it from me: they would have probably told me about their childhood and their parents, if I had asked. I remember, when I wanted to learn to count, I managed to count up to 39 and didn’t know the next figure. My grandfather Haim from Krichev prompted me, and then taught me to count up to hundred and further.

I also heard nothing about the army background of my grandfathers. Possibly in tsarist days my grandfathers could have borne arms, I don’t know exactly. At that time they didn’t draft Jews into the army willingly.

Abram and Haya-Ghita Ugolev had ten children. Their eldest son was lost during the World War I. I don’t know his name. Their eldest daughter, Vera, born in 1896, Milkina after her marriage, has already died. She had two sons. Unfortunately I don’t remember their names. The second son of my Ugolev grandparents was Lev, born in 1901, and he also died a long time ago. He had two sons: Mikhail, born in 1926, and Grigoriy, born in 1925. All members of their family lived in Kazan. Mikhail died five years ago [1999]. Another brother of my father, Pavel, was lost during the Civil War 3. Someone else was lost together with him, his brother or sister; today there is nobody to ask about it. My father Haim, born in 1903, was the fourth child in the family. He perished at the front during World War II, in 1944. Before the Great Patriotic War 4 he worked at a military prosecutor’s office of the Leningrad military district; during the war he was appointed a commissioner, he excited soldiers to go into the assault. He was lost near the city of Novgorod in action, near the village of Koptsy.

Another son, Ghirsha [affectionate for Grigoriy], born in 1908, also went through the Great Patriotic War and died in peace time. He had a son, Mikhail, who was born after the war, but he has also died by now. My father’s sister Dorah was born in 1906; after her marriage she was called Khutoretskaya. Before the war her husband, Yosif Khutoretsky, was a director of a sovkhoz 5 in Luga district near Leningrad. Before the war he held the position of administrative deputy director at the Veterinary College. Dorah and Yosif had two children: Semen, born in 1927, and Maya, born in 1932. One of my father’s sisters died at a very young age in 1910. Her name was Sofia.

The younger sister, Eugenia, Bryskina after her marriage, was born in 1913. When she divorced her husband Nikolay Bryskin, she decided to get her maiden name back, but the registration service employee muddled up things and wrote her family as Ugaleva. At present she lives in America in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Last year she reached the age of ninety. She left for the USA in 1992 together with her son Leonid, his wife Lyudmila and their sons Daniil and Eugeny. Sometimes they call me and my relatives. All of them are fine. The youngest sister of my father, Esther-Slava, Epstein after her marriage, was born in 1919. She died in 1999. She had a son Lev, three grandsons – Irina, Mikhail and Ilya – and one great-grandson, Mark, who is Mikhail’s son.

My grandmother and grandfather Tsypkin had four children. Their eldest son, Yakov, born in 1901, was an economic engineer. He died during the siege of Leningrad in 1942. He was about two meters tall. He had two children: the elder daughter Galina, who was born before the Great Patriotic War and the son Alexander, born in June 1941. My grandparents’ next son, Meir-Yosif was called by his family members Misha,sometimes Yosha. He graduated from the Polytechnic College in Leningrad as an engineer and research worker, technologist. He supervised the LAMITOMASH educational courses [courses for engineers of the Leningrad Society of Mechanical Engineering]. He was found guilty of some administrative infringement and was put in prison for half a year for it. By now he has already died. He had two daughters: Lyudmila and Margarita. Both of them live in Germany now.

My mum had one more sister, Sofia, Naimark after her marriage. All her life she worked as a bookkeeper. Before the war she married Oscar Naimark. He served at the front. After the end of the war he came back, and their daughter Lyudmila was born in 1948. Lyudmila has already died also.

I have only a distant memory of my stay in Komarovka at my Ugolev grandparents’. I remember that there was a large earth-road, very clean. The houses stood separately from each other. Right around our house there were large public apple orchards [they had no owner, the authorities used to appoint responsible persons in turns]. We went there to eat apples.

It seems that Komarovka was a large village. They moved about it using horse-drawn vehicles. My grandfather went to Krichev by horse. Sometimes I was put next to the driver and enjoyed the ride. I came to Krichev from Leningrad each summer. I remember that in 1939 we had a long stay in Komarovka. By that time my grandfather and grandmother Tsypkin had already died.

I remember Krichev a little bit better. Houses in Krichev were not high, but well-set. A cement factory was located there. In Krichev there lived probably tens of thousands of people. There was a road paved with concrete, homesteads; each house had an enclosed ground. The cows were taken to fields for grazing. There was no electricity supply yet. Both in Krichev and in Komarovka houses were illuminated by petroleum-lamps. At that time they hadn’t even heard about a water pipe. Each house had a well.

Probably in Krichev there were both synagogues and special prayer houses. And most probably in Komarovka there were not. It seems that my Krichev grandfather took me to the synagogue with him. At that time I was about six or seven years old. I have only a distant memory of that time. In Krichev there were Jewish schools. Someone of my friends-boys studied at a Jewish school in Krichev. I played games with them and got to know about Jewish school.

A lot of Jews lived in Krichev. They were employed in different businesses. Most often Jews were engaged in retail trade. My grandfather Haim also was in the small grocery business.

My father Haim Ugolev was born in 1903 in Komarovka. Up to the 4th class he studied at the rural school, and then he finished a seven-year school in Krichev. I guess that he never studied at a Jewish school, because there was no Jewish school in Komarovka. He was a good-tempered person, very honest. It was possible to ask him any question you liked and receive a detailed answer. He was well-informed about historical events; he had many books on history of the 19th century. He had books in English and in Persian languages – he could read English and Persian – but no Jewish ones. My father was a man of average height, he was heavy-browed, had not very thick hair. He was a pleasant man.

My mum [Pessya Ugoleva, bee Tsypkina] was born in Krichev in 1903 and lived in this city until her marriage. She was a tall, dark-haired woman with high cheekbones. She had authority with her colleagues. She was a hard-working, devoted mother and wife.

My parents were introduced to each other by their parents. My grandfather and grandmother from Komarovka and those from Krichev were acquainted with each other long before the wedding of my parents. When my father arrived in Krichev to continue his studies at the seven-year school, he stayed with an old friend of his father. This old friend was Haim Tsypkin, a tradesman. In the house of the Tsypkins my father met their daughter Pessya. Haim and Pessya fell in love with each other.

When my mum finished the seven-year school, she decided to leave for Leningrad to continue her studies together with my father. Mother decided to study at special courses, where she skilled in the profession of chemist/laboratory assistant, an analyst. My parents got married already in Leningrad. They simply went to a civilian registry office and registered their marriage.

My father was a member of the Communist Party [the All-Russia Communist Party of Bolsheviks]. He joined the Party when he arrived in Leningrad. He graduated from a faculty for students-workers and the Oriental College named after Enukidze, Persian department, in 1932. As he was a Jew, they didn’t send him to Persia for work [authorities did not trust Jews to work abroad]. But he was a highly educated person and they had to place him in a job somewhere. So after he graduated from the College, they sent him to expand the collectivization process. He was an editor of the Machine and Tractor Station newspaper, then of a regional newspaper, and later an editor of municipal newspaper in the city of Krasny-Sulin. This city is rather large; there is a large Metallurgical Industrial Complex. It was not renamed [after the breakup of the USSR in 1991]. My father made a long business trip: from 1932 till 1936 he worked in Azov and Black Sea territory. We visited him in Ghelendjzhik.

When my father came back to Leningrad from his business trip in 1936, he was appointed an editor of a newspaper at the printing house named after Volodarsky. My mum worked as a chemist/laboratory assistant at a factory in Kirov.

My parents were atheists. They didn’t observe Jewish traditions. Possibly we ate matzah – I don’t remember exactly, but most probably we did. We lived close to the synagogue, but never visited it. We had no Sabbath celebrations: at that time we had no Saturdays off – we had six-day weeks.

When my grandfather and grandmother Tsypkin came to Leningrad to visit us, they lived at our place. It was difficult for them to observe Jewish traditions and keep kosher in ‘the city of three revolutions’ [Leningrad was called this way by the Communists because it was this city where the Revolution of 1905 and the February and October Revolutions of 1917 took place] in the 1930s. It was dangerous: it could attract attention of active atheists and entail the arrest of all family members. I don’t remember them celebrating Jewish holidays, neither in Leningrad, nor by themselves in Komarovka.

My parents told me nothing about my grandfathers and grandmothers. At that time I – and my parents too – had different interests and troubles: I attended a kindergarten, later a school, and daddy and mum worked.

Daddy and mum spoke Russian. Sometimes, when they wanted to keep a secret from me, they spoke Yiddish. They didn’t teach me Yiddish though. I studied it during my visits to Krichev, talking to local boys. When I came back to Leningrad I used to forget Yiddish words.

I loved my mum very much. Every day she bought me cakes: real creamy cakes. Other children from our yard could have such cakes only once a year. The boys didn’t believe that my mum bought cakes for me in the nearest confectioner’s shop [cakes were very expensive at that time]. One day, when my mum was going home through our yard, I asked her to give me a cake. And she gave it to me immediately. Then I took it and gobbled it up. She asked me why I ate the cake right in the street. I answered that I wanted it very much. The next day I approached her again and asked her to give me the cake. Mum asked why I was going to eat the cake right on the spot. I answered, ‘Give it to me, I will show it to the guys.’ She gave me the cake and I showed the cake to the guys. They were amazed: ‘Terrific! Each day he has a cake!’

My father was a member of the Russian Communist Party, the Bolshevik party, and my mum was only a member of a trade union. They didn’t talk about politics at home. They taught me to look for human values. For example, at that time [in the 1930s] near Kirovsk [up-stream the Neva river] there was a Jewish collective farm. My parents held up Izya Feiggin, a boy as an example for me. He was a kind of relative, who industriously worked at this collective farm all summer long and earned money to buy boots for himself.

Our neighbors appreciated my parents very much. My mum was held in high respect. She had female friends at work, most of them were Russian. Most probably my daddy also had Russian friends.

My parents often met with their relatives. Uncle Yakov, the brother of my mum lived next to us. Most often we associated with the family of my father’s sister – the Khutoretskys: Dorah, her husband and children Maya and Semen. They lived next door. We also visited two of my father’s other sisters: Esther-Slava and Eugenia.

I was born on 16th April 1928. Now it is written in my passport that my name is Ugolev Alexander Efimovich. I changed my name after my son’s birth: I wanted to make his life easier.

I was born in Leningrad, attended all children’s educational establishments: a day nursery, a kindergarten, a zero class [a special class for children’s preparation to school].

I never went through the ceremony of bar mitzvah. But they arranged the brit for me. I guess my grandfathers initiated it. You see, my parents were atheists. It seems that among my family members only grandfathers Abram Ugolev and Haim Tsypkin observed Jewish traditions and practiced Judaism. Nobody else did. On the contrary, a lot of my relatives became Communist Party members and atheists. Probably, in the terrible time of revolutionary changes and Stalin’s mass repressions my uncles and aunts followed the law of self-preservation.

Since my childhood everybody called me Alexander, and Sasha or Sanya as a term of endearment. I found out that my Jewish name was Isaac only when I went to school. At first I didn’tlike its sound and became upset. But my father was a clever man. He showed me a portrait of Isaac Newton and told me how talented this scientist was, and I calmed down. I even took pride in my Jewish name.

All my life I’ve lived in the same house on Kurlyandskaya Street. As a child, I lived with my parents in the apartment no. 9, and now I live in the apartment no. 4, which is smaller. As a child, I lived in a two-room apartment. One room was 19 square meters large, and the other one – 12. Both rooms got all the sun. Two small gardens were located in front of our house. All windows of the apartment faced south. The kitchen was small. For its time that apartment was very good. There was no bathroom though. In the courtyard there was a cesspool and a laundry. The house was heated by stoves; a woodshed was situated near our door. In the house there was a sewerage system and cold water supply; we cooked meals by means of kerosene stoves. The house had an electric power supply. Gas appeared in houses only after the war. The furniture was good, both modern and old. The cupboard was mahogany with statuettes of horses – an antique one.

There were a lot of books in our apartment: books written by Lenin and Stalin, books devoted to the history of the 19th century, two books of Pushkin’s 6 works and a lot of others. When my father started working in the Office of the Public Prosecutor, there appeared a lot of juridical literature. We subscribed to the ‘Leningradskaya Pravda’ and ‘Smena’ newspapers [official Soviet newspapers]. I was a registered reader of a library. When a pupil of the 5th grade, I was given a souvenir book from the library as the best reader. I was fond of reading popular-science literature, adventures. My mum read almost nothing: she had no time to read; she had to run the house. My grandfathers probably had religious books.

I remember my first voyage by car. My father worked as an editor of the newspaper at the printing house named after Volodarsky. They celebrated the 40th anniversary of service of a type-setter. He started his work as a type-setter at the end of the 19th century. My father gave a report. Then there was a banquet. Children and grandsons of the type-setter sat at a table. I was the youngest among them. They made me sit down near the type-setter. He asked me, what I prefer to eat. At that time I liked fish and meat in aspic. And cakes too. They brought a tray full of cakes. I ate three or four of them. Then I was nauseous and got pain in my stomach. Those cakes were real: made using not margarine but butter. I was taken home by a car, which belonged to the printing house. When I came to my senses, I suffered terribly that the children from our yard and our neighbors had not seen me arriving by car.

At home I remained with our housekeepers. My mum worked all day long. When my mum was alive, Olga Pavlovna from Rostov, our housekeeper, worked for us. She was 75 years old. She was very tall, like a grenadier. I liked Olga Pavlovna very much; I kissed her and called ‘my pretty face’. She was Russian, a wife of a teacher of literature. Later she left and sent me a letter: ‘Good-bye, Sanya! Kissing you, your ‘pretty face’’.

I went to school at the age of eight, when our family returned from Krasny-Sulin. My father made a long business trip to Krasny-Sulin: he spent about a year there, and his family joined him there. When the lessons were over, our housekeeper gave me meals and I started to do my homework. I tried to do it quickly before five o’clock, because five o’clock in the afternoon was the time to listen to the radio broadcast for schoolchildren. There were no TV sets at that time. To listen to such broadcasts as ‘Theater at the Microphone’ or an opera performance over the radio, people changed their working hours with their coworkers. My favorite broadcasts for schoolchildren were presented by Valery Petrov, Yury Adamov and others. Most often they told us about outstanding revolutionaries. Most of all I liked Alexander Sergeev; his underground nickname was Artem. I liked him so much that I decided to name my future son Artem. And when my son was born, my relatives wanted him to be my father’s name-child. Understanding their determination, I decided to call my next son by the name of my father Efim, but to call my first son Artem.

If they sent me for a walk to the yard, I didn’t object. In general, I was a very disciplined child. In the first class I received good and excellent marks, and in the second grade - only excellent ones and was awarded an honorary diploma for my achievements in studies. My mum wasn’t afraid to let me go for a walk: she could watch me from the window. Sometimes I obtained her permission to go somewhere with the boys: we played different outdoor games.

During state holidays I went to look at demonstrations in Leningrad together with my father and mum. Before the war I went to demonstrations with my schoolmates. I liked patriotic songs by the composer Isaac Dunaevsky – they were melodious – and texts by the poet Lebedev-Kumach.

Before my sister Polina was born, my father left for an out-of-town military camp; he was not in the army before the war with fascist Germany. I have his photo, where he is shown in the uniform of a second lieutenant.

On 11th April 1938 my mum gave birth to my sister Polina, and died three weeks after delivery because of complications.

When my mum died, Masha Belenkova helped us about the house. We brought her from Belarus. At first she worked as a housekeeper at my father’s sister Esther-Slava. Then we took her away with us to Leningrad, because my sister Polina saw the light of day, and it was difficult for us to look after the baby and keep the house in order without my mum. Masha was Belarusian. Though she finished only seven grades, she knew everything that was necessary. I asked my father a lot of questions regarding my school studies, but my German lessons I checked only with Masha, because she was older than me and an excellent pupil.

In some months after my mother’s death another woman appeared in our house. She had to take the place of our mother. My stepmother, Galina Baranova, appeared in the following way: We were acquainted with Boris Abramov. He had an unmarried sister of 28 years of age. At that time Boris was a manager at the municipal training center, and my father was his subordinate at the Lenin branch on Ogorodnikova Avenue. So Baranov ‘pushed’ his sister to become my father’s secretary – he told her that my father was a widower. She was an old maid – lived in a room together with her brother – and my father had a self-contained apartment and he was young – 38 years old.

I tried to have nothing to do with my stepmother. She didn’t want me to call her Galya. And I wouldn’t have the heart to call her Aunt Galya or Galina Petrovna. She appeared in October 1938. And my sister was brought from the maternity hospital only in June 1939; she was a premature baby and physicians took care of her during a long period of time, especially knowing the fact of her mother’s death. Galina Petrovna was Russian. She had finished seven grades. She went in for sports: put the shot and was awarded a diploma for her results in a hurdle race. When she came to us, she left her job. At last she got everything she needed.

After my sister was brought from the hospital, I was lost in thoughts: how to call my stepmother? I was eleven at that time. Certainly I could call her Aunt Galya or Galina Petrovna. But by that time they brought home my younger sister, a baby who didn’t know yet that her mum had gone and that her daddy had a new wife. I spent a sleepless night and decided that is was necessary ‘to bring myself to perform a deed.’ There appeared a child, who didn’t know who is who; but she had a father and a brother, so she had to have a mother. That’s why from then on I started calling my stepmother ‘Mum.’ I asked no advice and decided it on my own. It means that my parents brought me up well.

Before the beginning of the war I attended School no.10 7, and after the end of the war – School no.277. Now this school is situated on Kurlyandskaya Street, 29. These schools were usual comprehensive ones, not Jewish. During the war it housed a hospital, after the war, for a short period of time, the hostel of the Kirov factory. Later, in this building there was the Technical college no. 9, which belonged to the ‘Metallist’ factory. At present, they are repairing this building and will house a boarding school for disabled children in it.

Before the war the school was mixed: boys and girls studied together, more than 30 pupils in a class. In elementary school – classes one to four – all subjects were taught by the same teacher. Nina Lorinova was our class teacher – a mathematician and a fine woman. Before the war we all together visited Andrey Kisselev, the author of the textbook on arithmetic and algebra. We visited him for no particular reason: just to get acquainted and have a talk. I liked many school subjects; in general I was an ‘omnivorous’ schoolboy. The teacher was strict, but her lectures were very interesting. I liked the lessons of Russian language, geography – when we left our classroom for the school courtyard with a compass and drew a plan of the district. I even enjoyed the PT lessons. In the first grade our teacher was often sick, and her lessons were replaced by singing lessons. At our school there was a choir and a percussion band. I wanted so much to play the castanets, but they didn’t have enough castanets for all of us – that’s why I played the bells At present I am still very sorry about it: sometimes I’d like to be able to play the castanets.

I never experienced any manifestations of anti-Semitism from our teachers. Our school staff was multinational. The head of the education department, Frida Moiseevna, was Jewish. She taught in senior classes. The director of the school, Petr Sokolov, was Russian. German language was taught by two sisters, russified Germans – their family name was Miller. My classmates never teased me or discussed Jewish topics with me.

After lessons I was engaged in additional physical training sessions at school for all comers. I liked to swarm up a rope and sway to and fro. In the gym hall there were bars and a horizontal bar for high jumps. Right at that time an idea came into my head: to try high jumping turning my back on the bar – some sort of the modern Fosbury-flop. At that time nobody tried it. As a child, I had many ideas, which later were embodied by clever people, and they took prizes for it.

At school I had neither friends, nor enemies; I treated everybody alike. In my house there lived one Russian friend, Yura Nikiforov, and one Jewish friend, Shura Imatovich. Together with Yura Nikiforov I attended kindergarten and elementary school, but I wasn’t that fond of him: he was very ambitious and arrogant. Most often I visited Vitya Yassinovich and our excellent pupil Igor Uspensky. He was a Jew, he was a more successful pupil than me and his character was closer to me.

At school I was a [Young] Octobrist 8, then a pioneer [see All-Union pioneer organization] 9. I was a son of a convinced supporter of the Communist Party. Though, to tell the truth, it wasn’t absolutely clear for me, why there were so many poor people and why our life was so hard. But in 1937 we didn’t even think about it: it was dangerous [see Great Terror] 10.

I have a few clear memories about political events in the country before 1941. I asked my parents no questions. I sussed things out for myself, and my opinion was formed from broadcasts and newspapers. I made conclusions myself. Some things seemed strange to me. For example, in 1935 in the USSR there were five marshals. Later only two marshals remained: a metalworker, Klim Voroshylov 11 and a Cossack junior leader, Semen Budenniy [Budenniy, Semen (1883-1973): USSR marshal (1935), Hero of the USSR (3 times: in 1958, 1963, 1968), commander of the 1st Cavalry (1919-1921), Deputy People’s Commissar of Defense department (1939-1941), commander of group of armies (1941-1945), delegate of the USSR Supreme Soviet (1937-1973)]. What happened to the rest of them? But the main public prosecutor Vyshinsky’s speeches for prosecution against ‘spies and traitors’ were so convincing … [Vyshinsky, Andrey (1883-1954): Soviet diplomat and lawyer, Professor of Law and Chief Prosecutor in Stalin’s purge trials (1934-1938), Foreign Minister (1949-1953), Deputy Foreign Minister and permanent delegate to the UN]

Each summer we left for Krichev to see my grandmother and grandfather, or for Komarovka. I remember my first journey by train: we went with my mother to Krichev, to Grandmother and Grandfather. At that time I was four years old. It wasn’t a shock for me. We went in a carriage with numbered reserved seats. We traveled for more than a day. We were eating all the time: chicken, boiled eggs, etc.

In Krichev I went for a swim in the Sozh River. In Ghelendzhik, where my daddy worked, I swam in the Black Sea. Sometimes I took a bath with sea-water. After a while they pulled out a cork and I watched ‘the sea’ flowing away from a small bath. I fell into raptures over it.

On birthdays all my relatives gathered, brought gifts, ate tasty meals, talked. We celebrated only state holidays: 1st May, Soviet Army Day 12, etc. We didn’t celebrate Jewish holidays, because my family members and our relatives were atheists.

On 18th October 1938 the Moscow cinema was opened – the first cinema in Leningrad with three halls. In all three halls they showed the film ‘Chapaev’ [a classic from the year 1934, directed by Georgi and Sergei Vasilyev, based on the life of the Soviet military leader Vassiliy Chapaev 13. Up to that time we used to visit ‘Udarnik’ cinema – now it’s called ‘Record’. Zina Yaruk, a friend of mine, a Belarusian, got tickets for us at a low price of 50 kopecks.

I remember an episode from my school life. In our court yard there was a lath fence. Before the war I liked to play ball games in the court yard. I wore trousers, which my stepmother remodeled using trousers of my father. Its texture was very close. People called it ‘devil’s skin.’ My ball rolled under the lath fence. Looking around, to avoid reproof of adults, I started climbing over the lath fence to take the ball. Accidentally my trouser-leg was caught on the lath fence. The result was unexpected: the trouser-leg remained safe, and the lath fence was broken off.

In 1944 I returned to Leningrad from evacuation. People, who lived in the city during the blockade 14, warmed their houses using material at hand. They used everything: books, furniture, etc. But that lath fence in our court yard remained safe as it was before the war. Only one part of it was broken – by me. Nobody touched it, though it was made of wood and could have been used for heating.

My sister Polina didn’t attend a kindergarten, because she had ill health from her birth. She attended a seven-year school on Kurlyandskaya Street. Later she finished a secondary school [10 grades]. After that she studied at a commercial college in Krasnodar. At school she studied so-so. She had no special abilities, no schoolmates. Soon after leaving school she got married. Her husband was a senior lieutenant, Ushkov Victor. She gave birth to a daughter, Olga. After the putsch of 1956 15 they lived in Hungary, where her husband served, later in Krasnodar and other places. Polina worked as a sales assistant in different shops. She returned to Leningrad after she divorced her first husband and soon married a man, who was older than she, a captain in retirement named Alexander Alexandrov. Later they also got divorced. Then she married Valery – I don’t remember his surname – and lived at his apartment. She got acquainted with Valery during her figure skating training sessions: he was a brother of her coach. Polina worked as a sales assistant in a shop near the Baltic railway station. She had numerous customers. At that time in the context of serious deficiencies, it was her luck to work in a shop – she was able to get whatever she liked. Later she retired on a pension and didn’t work any more. Polina got ill with an oncological disease. She sank all her savings into a financial pyramid and lost almost all money. The rest she spent for treatment of cancer. Polina underwent chemotherapy, but without success. The treatment was very expensive – all our family helped her to find money. The malignant growth was inoperable, and it developed into a sarcoma. Polina died at home [in 1999] in the presence of her daughter Olga.

News about the beginning of the war reached me in Novgorod, at the relatives of my stepmother Galina. At that time I was 13 years old. In two weeks I went back to Leningrad by train and arrived there in July 1941. At that time my stepmother was recruited for digging entrenchments in the city suburbs. On 8th September 1941 the blockade of Leningrad was started.

At the beginning of the war my father worked in the Leningrad military district headquarters [(in the prosecutor’s office, which was located in the Peter-and-Paul Fortress]). Later, at the beginning of August he was recalled to the military unit. I saw him off. When my stepmother came back from digging entrenchments, he had already left. My father left for the front in the rank of senior lieutenant. Later he was made captain. When we wrote him letters, we addressed envelopes to division headquarters [prosecutor’s office].

A sister of my stepmother, Valya, arrived from Novgorod. She was a student of the Leningrad Chemical and Pharmaceutical College.

On 1st September our school was closed, several pupils and I studied in an air-raid shelter in the house next door. Someone said that the blockade had already begun. At first we didn’t believe it, but when the authorities reduced the daily rate of foodstuff, we felt it. Ration cards appeared in June. At first the daily rate of bread per capita for children and dependents was 400 grams, later 300 grams, later 250 grams, 200 grams and, at last, 125 grams. It was a small, but heavy piece. It contained a small amount of flour, but mainly cellulose and sawdust. Strangely enough it seemed to me that ration cards existed not too long.

In February 1942 I lived at Sofia Naimark’s, my mother’s sister’s, on Chaikovskogo Street. One day I came to her and she told me that my stepmother Galina had visited and informed her, that our family would be sent into evacuation. We were evacuated in the middle of February 1942. We moved by divisional lorry, heavily loaded with something, to the front headquarters. The lorry had to return back to Leningrad. At first I decided not to leave for evacuation. By that time they had already increased the daily rate of bread up to 300 grams. It was almost wholesome bread. My stepmother raised objections against my stay in the besieged city. She said that she was responsible for me to my father. We all – me, my stepmother, her sister Valya and my sister Polina – went safely.

My father sent me a tank man’s helmet. This helmet stood me in good stead: once on a rough road our lorry bobbed us up and I hit my head against a sheet of plywood above my head. A nail projected from it. I wore this helmet. The nail stuck in my helmet, and I wasn’t hurt. We were brought to a village near Kobona on the opposite bank of Ladoga Lake [Road of Life] 16, to back areas of division. In back areas of division there was everything necessary for normal life: hairdressing salons, shoe workshops, photo studio and so forth. We were sent to shoemakers. There we had a rest and were replete with food for several days. My stepmother’s sister Valya cooked boiled rice. Then we packed our things: we had ten packages. My stepmother left my father’s coat in the charge of her brother Boris. Boris was just going to use it to warm himself, but my stepmother Galina didn’t allow him to. She said, ‘This coat belongs to Efim. I leave it to your care. When Efim returns home from the front, he will wear it.’

We continued our way to Tatarstan [a Soviet autonomous republic] by train. On the way a lot of passengers died from weakness or ileus [intestinal obstruction] because they pounced on the food. We reached the town of Tutayev in Yaroslavl region. Before the revolution it was called Romanov. There we lived two weeks in a school building, grew fat, visited bath-house, cleaned our clothes and linen in a steam chamber [delousing station]. I was cold and decided not to clean my clothes – went on with lice. One day I caught a louse in creases of my clothes, and investigated it in all its bearings: its organization, the way it bites and moves – all in all, notwithstanding the war and starvation, I kept my thirst for knowledge. At last we reached Agryz – 37 kilometers to the north from Izhevsk, the capital of Udmurtia, in Tatarstan. We were placed into two rooms, in the house of a young woman. There we spent winter and spring. In Agryz there gathered all members of the Baranov family – relatives of my stepmother: Grandfather Petr Mikhailovich and Grandmother Evdokia Vassilyevna, the elder brother of my stepmother, Boris, with his family.

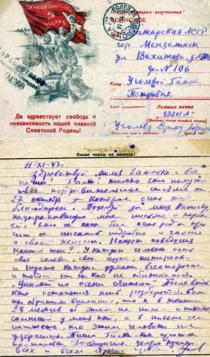

I carried on a spirited dialogue with my father by correspondence. I finished the fifth grade before the war in Leningrad, I started studying in the sixth grade in the village of Muslimovka in Tatarstan, and later we (the whole Baranov family) moved to Menzelinsk, where I finished the sixth and the seventh grade.

Aunt Kapitolina worked in Agryz in a soup-kitchen catering for the party workers, and her husband, Vassiliy Shabokhov, got acquainted with the director of the ‘Sheepman’ state farm in Muslimovka district. They agreed, that he would work in this state farm as a forest warden, and then as a forestry chief. We lived in Muslimovka during 1942 and 1943. Later Shabokhov had a squabble with the state farm director and we had to move to Menzelinsk. We lived there on Konny Square. There I finished the seventh grade. It was a real city: there was a cinema and a cultural center, where evacuated people gathered for rest and for amateur art activities.

We received news about our relatives. A central information bureau on evacuees was organized in Buguruslan. Several times we wrote to them and received information on many of our relatives.

Grandfather Abram Ugolev and Grandmother Haya-Ghita Ugoleva together with their daughter Esther-Slava were caught by the war at home in Komarovka, in Belarus. They moved their family out of the war zone to Russia, because the Germans could make away with them as Jews. They reached Penza. Grandfather Abram died there in 1941.

Their daughter Eugenia was an army person; she worked in rear services during the war and was awarded medals. She was married to Nikolay Bryskin, a Navy man. One day after the end of the war we were speaking with him, and I mentioned Yury Gherman, a well-known Soviet writer. Nikolay Bryskin told me, that Yury Gherman had given him a photo as a keepsake. At first I didn’t believe him. Then Nikolay took the photo down from the shelf: Yury Gherman in the uniform of a seaman, wearing a sailor’s cap). It was signed: ‘To my friend Nikolay Bryskin from Yury Gherman – remember me.’ During the war Eugenia was in the army, in a housekeeping unit, I don’t exactly know where. It seems to me, all the war time she worked in a naval housekeeping unit in besieged Leningrad. At that time she already had a son, Leonid. They survived, thanks to the fact that she received an army ration.

I don’t know where my father’s elder sister Vera was during the war. She also survived. After the war she returned to Leningrad, where she lived and worked in a hostel of the Leningrad College of Railway Transport. Later she left for Karelia, where she died.

I know nothing about Lev, my father’s elder brother.

During the war the younger brother of my father, Ghirsha, was in the front-line forces – he was a private, survived and married Mira, a Jewess. She gave birth to their son Mikhail [in 1949]. After the war they moved to Leningrad and settled in our house, in the apartment no.88. They were Communist Party members Ghirsha died in a hospital in Leningrad some time in the 1970s. His son Mikhail also was very unhealthy; he often underwent medical treatment in different sanatoriums. He loved his mother Mira very much. He was married twice. He died young in 1990. Mira outlived both her husband and her son. She kept in touch with me and with one of her daughters-in-law. She wanted to live in an old people’s home and asked me to assist her in this matter, but I refused, because I thought she wouldn’t be fine there. She died at the beginning of the 1990s.

The brother of my late mother, Meir-Yosif, was in the army during the war. Before the war he graduated from the Polytechnic College. In my opinion he was a captain of the engineering and technical department. In wartime he already had one daughter, Lyudmila – same age as my sister Polina –, and after the war his second daughter, Margarita, was born. At present both his daughters live in Germany, as for Meir-Yosif, he died a long time ago.

My mum’s other brother, Yakov, died during the siege of Leningrad in 1942. He was an engineer and economist. He had two children. His elder daughter, Galina, was born several years before the war, I don’t remember the date. His son Alexander was born in June 1941, in the first days of the war. Before the war they lived not far from me in Derpt Lane. Their mother was the second wife of my uncle Yakov. Her name was Alexandra Ogneva, after marriage Tsypkina,a Russian.

My mum’s sister, Sofia Naimark, lived in Leningrad throughout the siege period. Before the war she worked as a bookkeeper. Before the beginning of the war she got married. Her husband was a soldier at the front, in a tank unit. I saw him off to the front. He survived and returned home. He was a long-liver. His sister moved to America a long time ago. After the war she sent parcels to Leningrad, and even visited us and bought a two-room apartment in Leningrad, on Nauka Avenue. It happened at the time when the Soviet authorities permitted to organize building societies [at the end of 1980s] to give people a chance to buy apartments. His sister immigrated to America before the war. Now America is crammed full of Jews.

My cousin Semen was a little older than me when the war broke out. He was born on 28th August 1927. His sister Maya was born in 1932. Their father Yosif [the interviewee’s father’s brother] also was at the front and returned home. Before the war he served at the railway guard forces,Fontanka embankment, 117. During the war he served in railway troops. During the war Dorah, a sister of my father, together with Semen and Maya, stayed presumably in Yoshkar-Ola [capital of Mari Republic].

During the war we lost my father. He was killed at the front. It happened near Novgorod, in the village of Koptsy, on 14th January 1944. As always, they also wrote us that he had died ‘a hero’s death.’ Later his company commander wrote us that my father had been the first to go over the top to launch an attack and was shot.

The brothers of Aunt Dorah’s husband, Ilya and Alexander Khutoretsky, also perished at the front. Ilya was a private, and Alexander probably served as an officer; before the war he finished a college. I know that none of my relatives were taken to forced labor in Germany.

As soon as the blockade of Leningrad was lifted, we decided to return to Leningrad. It was in 1944. My aunt Sofia Naimark got to know by chance, where we stayed during evacuation and sent us letters. She wrote that she had moved to Izmailovsky Prospekt. She had a room in a large communal apartment 17. A chief mechanic of the Kirov plant also lived in that apartment. He sent us an invitation and we returned to Leningrad, to Izmailovsky Prospekt. It wasn’t difficult to return to Leningrad.

We had a long way by Kama River, and then by Volga River on board a motor ship. The authorities of the city had no objection to our return, because we were a family of a front-line soldier [Editor’s note: After the end of the war authorities decided to check the status of citizens and did not permit everyone to get back to Leningrad: to return one had to receive an invitation card from someone who lived in the city]. After our return my stepmother went to the housing department of the house where we had lived before the war, and got the keys to our apartment. During the war it was occupied by our house-manager, so our apartment appeared to be well-kept and available. All things were safe, except for the 5th volume of French history and two textbooks of English language.

One day, as I was walking around the city I saw an advertisement of the Leningrad Military Mechanical Technical School. They offered two very attractive items: occupational deferment and a worker’s food-card [see Card system] 18. I didn’t worry about deferment at that time – I was only 16 years old – and the worker’s food-card, which gave possibility to receive high food norm, could be of great use for me. I quickly submitted my documents to this technical school. My school certificate was full of excellent marks, so I entered it without problems. However, all new students were forced to work on the reconstruction of the city. I was a disciplined and law-abiding person – I didn’t object. Later I got to know that a worker’s food-card was offered not only by this technical school, but practically by each educational institution. So I had a choice, but at that time, when I was 16, I didn’t think about it. When I became a student, I refused to study the German language, and chose English.

After the war Leningrad seemed to me not that much destroyed. To tell the truth, instead of some houses there were bomb-holes, and the dome of the Troitsky Cathedral [a well-known Orthodox Cathedral] was damaged a little.

After the war, in 1946 the Khutoretskys – Dorah, her husband Yosif, their children Semen and Maya, who still went to school – moved to our house on Kurlyandskaya Street. They lived next door. I often spent a lot of time there. They gave me food. I went back home only to sleep. I slept on a box in our kitchen, because one room was occupied by my stepmother and sister Polina, and the other one my stepmother hired out. I didn’t consider the situation to be infringing: I understood that it was necessary to have a source of income. During my studies in the technical school I lived at the Khutoretskys’, and then with Sofia Naimark, my mother’s sister. After the war with Germany the national economy collapsed, food was distributed according to special cards. There was shortage of tasty meals and good things. I remember that soon after the war someone came to my aunt Sofia and brought melted butter with honey in a braided lime bark basket. It was very tasty.

On 18th April 1959 I moved from the apartment no.9 to the apartment no.4, as my stepmother and my sister had changed our apartment for two smaller ones. They moved to Gas Prospekt #52, and I moved to the same house and the same entrance, where I lived earlier, but in the apartment one storey lower. There was a bath-room and not many neighbors; it was good. My neighbors were elderly Russians, a married couple.

Our neighbors – not Jews – considered our return to be natural. My father was one of the first persons, who had settled in this house before the war. Our neighbors thought that our return was a sign that life in our house was all in the day’s work.

When we returned, my stepmother Galina got a job connected with the passport system. Her salary was 250 rubles per month – it was very little for that time. My worker’s food-card helped us. One day the technical school director issued an order docking me of my scholarship. All students of the technical school gathered to look at this order and at me. And the point was that I could receive either pension for my father, lost at the front, or a scholarship. My scholarship was only 25 rubles, and the pension – 170. I chose the pension. But in spite of all my efforts, we had a hard time. One day I went to the black market together with my aunt Esther-Slava Epstein, my father’s sister, to buy a coat for myself. We paid 150 rubles for it and the sum was rather large for us: my mother-in-law had to put money aside for this purpose.

Right after the end of the war I knew nothing about the emigration of Jews to Israel. I heard about it only in the time of Khrushchev’s 19 ‘thaw’ [see Twentieth Party Congress] 20. At that time I got to know that Golda Meir 21 was the Israeli ambassador to the USSR. I could not bring myself to immigrate to Israel: I never could imagine myself in another country.

I already had some experience of living in different cultural surroundings: I lived in Tatarstan from February 1942 till August 1944. Their language, literature, life, culture – everything was different. For me it was unusual and difficult. In the post-war period I thought about politics rarely. However, attacks on Jews went on. For example, I didn’t manage to watch any performance of the Jewish theater, though I wanted to so much. When Mikhoels 22 was killed they closed his theater.

The Doctor’s Plot 23, which started after Stalin’s death, suggested to me that having killed Mikhoels, the authorities began to repress his family and other Jews. I didn’t believe that the doctors were guilty of the death of the Leader.

I remember that when I got to know about the illness and death of Stalin I didn’t believe it at first, and later I was surprised that the medical certificate about his death was signed not by the Minister of Public Health Services, but by a doctor in charge of the case, a candidate of medical sciences [see Soviet/Russian doctorate degrees] 24. I wanted to go to Moscow to attend Stalin’s funeral, but they didn’t let me go. And it was good: if I had gone there, I could have been hurt in the crush.

I took neither the Hungarian [1956 Revolution], nor the Czech events of 1968 [Prague Spring] 25 very much to heart. During the Czech events a jazz band from the Czech Republic performed on tour here and I thought that if the Czech orchestra came here to play, it meant that in Czechoslovakia everything was fine.

I took a grave view of the rupture of diplomatic relations between the USSR and Israel. Neither the Torah, nor the Bible tells about the Arabs, but Jews and their State are mentioned there. I didn’t like that our country supported Egypt and Palestine in their struggle against Jews. When Nikita Khrushchev went to Egypt in order to decorate Gamal Abdel Nasser and his minister with Soviet government awards, I was shocked. When Israel managed to gain victories, I obtained satisfaction.

After the end of the International Youth Festival in Moscow in 1957 [biennial International Youth Festivals took place in different countries and included a great number of cultural, social and political events] I took a great interest in professional dancing. Up to then I played volleyball – since 1949. At that time I worked at the central design office no. 34, in the new office building on Borovaya Street. When our office was moved to ‘Arsenal’ enterprise, I played volleyball for ‘Arsenal’ championship; I was a skilled volleyball player.

One day I was going home from a training session and saw a large board with the following advertisement: ‘Ball-room dancing parties.’ There they studied to dance foxtrot and tango, and during the campaign against ‘cosmopolitans’ 26, before 1957, these dances were forbidden as immoral and alien to the Soviet people. Young people had an opportunity to meet only at dancing classical dances. In the Palace of culture named after Gorky dancing parties went the following way: a Viennese waltz, a figured waltz, waltz galop, polonaise and mazurka, and in the end – final waltz. There were five or six polka dances. We didn’t study Jewish dances. In the Vyborg palace of culture, Vladimir Shuvalin, a soloist of Alexandrov’s ensemble performed a tailor’s dance, which included elements of Jewish dances.

After finishing the technical school, I worked in the central design office no. 34 for Navy armament named after Ilya Ivanov, as a designer. Later I worked in the central design office no. 7 at ‘Arsenal’ enterprise, and later yet, as a designer at the factory named after Kalinin. And after that at the ‘Metallist’ factory. From there I moved to the Engineering Castle to Ghipro-Energo-Prom – a State Institute for design of electro-technical enterprises.

There were no obvious conflicts at my work or during my study because of my Jewish origins. But sometimes strange things happened, for example: I failed to enter the Military Mechanical College. They told me that I got a poor mark in the literature exam. It happened in 1952, when I worked at ‘Metallist.’ Later I passed the examinations and entered the Northwest Forestry College. I finished the first course, but didn’t continue my studies there.

I had friends. It was of no importance for me whether they were Jews or not, but I was interested if they were Jewish or not. My first wife was Jewish. We were introduced to each other by Mira Israilevna, a friend of my aunt Dorah, elder sister of my father. Her name was Inna Moisseevna Graevskaya. She still lives in Leningrad. She is one month and 13 days older than me. I got acquainted with her in 1950. But our marriage failed. She wanted to have a child very much, me too. But she lived with her mother, who was very sick. I also lived in bad conditions: in the same room with my sister and stepmother. At that time young mothers were permitted to take maternity leave two months before and two months after childbirth. And then it was necessary to start working. What to do with a two-month-old child? Certainly, it was possible to stay at home and look after the child, but lose the job. Inna even could work at home, giving private lessons, but for this purpose it was necessary to have a separate apartment, and her apartment on Ghatchinskaya Street was not. I visited her only twice during a period of several years; I even do not remember her apartment. When she visited me, we could stay in my room together for a short period of time. So finally we decided to give up the idea of marriage.

At present she lives at another address, behind the Polytechnical College. At that time when a man appeared near her, Mira Israilevna reported it to me. And I went to see Inna again: so, I behaved as a dog in the manger: if I can’t have her, nobody will. Until now I can find no excuse for my behavior. Now she has neither a husband, nor children. We get in touch as friends, but not often: we congratulate each other on the occasion of birthdays, call each other, and borrow money from each other during hard times. I visited her at the Conservatoire. She worked as a concertmaster in an opera studio at the Conservatoire.

In 1981, at the beginning of April, the ‘Metallist’ administration gave me two tickets for a paid trip to a rest home in Komarovo [suburb of Leningrad]. There I got acquainted with my present wife, Elena Petrovna Shikalova. She was born in the city of Glazov on 25th May 1954. She is Russian. Her father’s name is Peter Shikalov, born in 1924. Her mother Inna, born in 1926, is a teacher. At present they are pensioners. Peter worked at Chepetsk Mechanical factory, where 80 percent of Soviet uranium was smelted. His health is poor now. He lives in the family of his younger son [in his apartment].

Elena has three brothers, all of them are older than her, and all of them live in Glazov. The oldest brother Mikhail graduated from art school. He has a son, Denis. At present he lives in Germany with his family. The second brother Sergey graduated from Perm Medical College. There he got acquainted with his wife. They have two children: Maria and a younger son.

I got acquainted with Elena during my annual leave. For the first time in my life I managed to arrive in the sanatorium in time. Usually I came to have a rest in the afternoon and had second shift dinner. And that day I arrived early. I asked employees of the sanatorium, ‘Girls, what can you offer to a young handsome man of average fatness in the prime of life? I do not drink alcohol, I do not smoke, do not romance…’ I tried to publicize myself. They asked me, ‘Do you mind if we place you on the second floor, where mainly women live? I answered, ‘Sure, I do not mind! I promise to behave properly! If I depart from my word, you can kick me out immediately!’

I lodged in a large room. To tell the truth, the room was slightly damp. Later I went downstairs and saw a man who was about 35 years old. We got acquainted, I told him about myself, and he told me about himself: he came from Petrozavodsk, visited Leningrad and arrived here to have a rest in the sanatorium. We made friends, went for a walk, talked a lot. Unintentionally I mentioned that soon I had my birthday. On that day – 16th of April – my friend arranged an unforgettable festival for me: he gave me a bottle of my favorite wine as a gift, ordered fried fish, smoked fish, etc. and treated me to it.

Next morning I went out of my room to take a shower. I soaped myself and heard a woman’s voice: ‘Why are you washing yourself in the women’s shower-room?’ I asked, ‘And why do you think that it is the women’s?’ She answered, ‘Because only women live on this floor!’ I said, ‘Not only women, I also live here!’ She replied, ‘You are lodging on the women’s floor illegally!’ I was surprised: ‘Where did this legalist come from?’ She answered, ‘From Glazov, do you know it?’ I said, ‘I know everything: it is situated on the way to Perm and Sverdlovsk through Cherepovets, one day journey from Leningrad.’ She said, ‘You know everything indeed; I already noticed that.’ You know, several days before I had won two quiz-games in that sanatorium.

Later I got to know that her name was Elena. We found plenty to talk about. After dinner I invited her to play badminton. It was Sunday and the rental store of sports equipment was closed. Elena got upset, but I had brought two rackets with me from Leningrad and she was delighted. Elena is 25 years younger than me. I showed her magazines with photos of well known dancing couples: elegant men and beautiful women in evening dresses with décolleté and a cutout back. Elena considered these photos to be nearly pornographic. She stayed in the sanatorium for a long time, and I came there to see her on my days off. We had a stormy romance. I used to spend nights in her room. She told me about herself: in Glazov she worked as a teacher at a kindergarten. She graduated from a Pedagogical School in Glazov and Perm Pedagogical College by correspondence. Elena is an extra-class teacher. At present she teaches one very sick child. She took a fancy to him and doesn’t want to change this work for a better-paid one.

That summer I took her to Leningrad to my room – 12 square meters. I told her about my work, my wages. At that time her salary was higher than mine. And that was the moment when I made a stupid action. We’d better have handed in an application to a civil registry office and they would have given us two months to think everything over. During that period of time I would have got acquainted with her parents, they would have felt at peace with themselves, they would have accepted me in their house. But we were in love with each other. Elena didn’t want to wait; she told her parents that she was going to leave for Leningrad to live with me. She left her job, her apartment in Glazov and arrived in Leningrad. It turned out, that we did everything to complicate our life. They didn’t want to register Elena for a long time, therefore she couldn’t find work: she did temp work, unofficially. For a very small salary she went to nurse a child out of the city – she had to spend four hours to get there – her working day lasted ten hours.

On 19th February 1983 we got married. It was a historic day not only for us, but also for the country: the day of abolition of serfdom[it happened on the 19th of February 1861] in Russia. But in contrast to peasants who celebrated their freedom, we celebrated our interdependence.

In 1984 our son Artem was born. By now he has already finished school and entered the St. Petersburg University, the Geographical Faculty: he is a second-year student. He is very sociable and curious. He has no family of his own yet. I tried to tell Artem about Jewry. But he and my wife don’t like to listen to my stories. I told my son that he is half Jewish very early, but he hasn’t become interested in it yet.

After the end of the war I didn’t celebrate Jewish holidays. It seems to me that the synagogue was closed for a long period of time. Now I visit the synagogue on Jewish holidays from time to time. For some time I even had meals in a Jewish soup-kitchen. My wife doesn’t want to accompany me for Jewish holidays, meetings, concerts, but I go sometimes. My wife and my son celebrate New Year’s Day as a state holiday and Russian Easter, because my wife is Russian.

From Jewish tradition and culture our family chose only the book ‘120 Recipes of Jewish Cuisine’. Jewish cuisine was highly respected by Inga Fedotovna, my mother-in-law, now deceased. She cooked mezenos [sweet pastry], tsimes, forshmak.

I have few friends now, some of them are Jews. The proportion of Jews among my friends approximately equals the proportion of Jews in the population of St. Petersburg.

When Mikhail Ugolev, a son of uncle Ghirsha was alive, he visited us. After Mikhail left for the army, his wife often came to see us. She missed her husband very much and I tried to distract her someway. Her relatives complained about her spending time with me, and after the end of the war, when her husband returned home, they divorced.

At present Semen and Nina Khutoretsky – his wife – live in the same house with us. Sometimes we visit each other on business or for no particular reason; we help each other if we can.

I’ve never been to Israel. I have no relatives there, except Irina Epstein, the elder daughter of Lev Epstein, my cousin. He is a son of Esther-Slava Ugoleva, Epstein after marriage, my father’s sister. He has two children born in his first marriage: Irina and Mikhail, and a son born in his second marriage, Ilya. I remember Irina as a little girl, but now we are not in touch. Lev, her father, informs me about the way she lives. I didn’t find any special opportunity to visit Israel until 1989, and I didn’t search for it because of my laziness. Though I guess it could have been an interesting trip.

The state authorities didn’t really disturb me because of my Jewish origins. It can be explained by the fact that I didn’t make a show of my Jewish origin. I knew that the authorities didn’t like Jews, therefore I tried to hide myself: I even changed my name and my patronymic in my birth-certificate and in the passport. Earlier I was registered as Ugolev Isaac Haimovich, and now I am Ugolev Alexander Efimovich. I did it for the sake of my son. I wanted him to have the patronymic Alexandrovich, not Isaacovich. This will make his life easier.

Before Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev 27 came to power I couldn’t keep in touch with my relatives abroad 28. It was dangerous: authorities supervised all contacts of the citizens with foreigners and didn’t approve it. At present Eugenia Ugoleva, after marriage Bryskina, my aunt and my father’s sister, her son Leonid Bryskin, his wife Lyudmila and their children Daniil and Eugeny live in the USA. They left in 1992. They live in the city of Minneapolis, Minnesota. Sometimes we call each other, I wrote to Aunt Eugenia twice. It would be better to communicate more often, you see, she is already 90 years old, and Leonid is not young either.

Before Perestroika 29, Lyudmila – (daughter of Sofia and Oscar Naimark – left for the USA. But we are not in touch. I know that in the period of Perestroika she visited St. Petersburg.

After 1989 life in Russia changed a lot. Capitalism came to our country. It isn’t easy for people of my age to accept such global changes in our social order. I considered Gorbachev’s Perestroika to be great nonsense. If Shatalin, G.A. Yavlinsky and other scientists-economists offered the ‘500 Days’ program [this program was created to improve the economic situation in Russia in 500 days], it is necessary to use it and carry out reforms. What is the purpose to philosophize and search for historical basis for changes in the USSR, if there is a specific program of gradual, step-by-step economic and political transformations? Why not supervise the process of reforms day by day according to this program? You see, if you sit on your place and reflect, manna would not fall down from heaven, and it was necessary to pay debts to the world community. During Perestroika there was no planning and no order, even some sort of communists’ order.

When I got to know about the fall of the Berlin wall, I couldn’t conceive of this fact. I used to think that Western Berlin is our opponent and Eastern Berlin is our ally. I thought, that life in the Eastern part of Berlin was better, than in the Western part, but it turned out to be absolutely on the contrary.

After Perestroika nothing much changed in my life. My personal economic stability is expressed in the fact that I live as poorly as before. To tell the truth, our cultural life became richer. It became possible to speak about politics, to express your own views, but within reasonable limits. I had a sensation of the decline in anti-Semitic policy.

Now I go to the synagogue sometimes, I am a client of Hesed 30. I didn’t receive any assistance from foreign Jewish organizations. Sure I’d like to receive it: it isn’t easy to make ends meet. But I’m not depressed.

I feel community life to be very active. I’m pleased that we have a lot of Jewish organizations. If I were a wealthy man, I would like to join the Jewish donor’s circle. At the Synagogue and Hesed Center I receive souvenirs and food packages for each Jewish holiday, I attend concerts, I’m a registered reader of the Hesed library.

I’m very grateful to Jewish organizations, which help me live, send food packages for holidays, arrange concerts. I thank JDC [Joint] 31, Hesed Center and Mirilashvili [a Georgian Jew – a businessman and a sponsor] personally for their charitable activities.

Glossary:

1 Russian Revolution of 1917: Revolution in which the tsarist regime was overthrown in the Russian Empire and, under Lenin, was replaced by the Bolshevik rule. The two phases of the Revolution were: February Revolution, which came about due to food and fuel shortages during World War I, and during which the tsar abdicated and a provisional government took over. The second phase took place in the form of a coup led by Lenin in October/November (October Revolution) and saw the seizure of power by the Bolsheviks.

2 Jewish Pale of Settlement

Certain provinces in the Russian Empire were designated for permanent Jewish residence and the Jewish population was only allowed to live in these areas. The Pale was first established by a decree by Catherine II in 1791. The regulation was in force until the Russian Revolution of 1917, although the limits of the Pale were modified several times. The Pale stretched from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea, and 94% of the total Jewish population of Russia, almost 5 million people, lived there. The overwhelming majority of the Jews lived in the towns and shtetls of the Pale. Certain privileged groups of Jews, such as certain merchants, university graduates and craftsmen working in certain branches, were granted to live outside the borders of the Pale of Settlement permanently.3 Civil War (1918-1920)

The Civil War between the Reds (the Bolsheviks) and the Whites (the anti-Bolsheviks), which broke out in early 1918, ravaged Russia until 1920. The Whites represented all shades of anti-communist groups – Russian army units from World War I, led by anti-Bolshevik officers, by anti-Bolshevik volunteers and some Mensheviks and Social Revolutionaries. Several of their leaders favored setting up a military dictatorship, but few were outspoken tsarists. Atrocities were committed throughout the Civil War by both sides. The Civil War ended with Bolshevik military victory, thanks to the lack of cooperation among the various White commanders and to the reorganization of the Red forces after Trotsky became commissar for war. It was won, however, only at the price of immense sacrifice; by 1920 Russia was ruined and devastated. In 1920 industrial production was reduced to 14% and agriculture to 50% as compared to 1913.4 Great Patriotic War

On 22nd June 1941 at 5 o’clock in the morning Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union without declaring war. This was the beginning of the so-called Great Patriotic War. The German blitzkrieg, known as Operation Barbarossa, nearly succeeded in breaking the Soviet Union in the months that followed. Caught unprepared, the Soviet forces lost whole armies and vast quantities of equipment to the German onslaught in the first weeks of the war. By November 1941 the German army had seized the Ukrainian Republic, besieged Leningrad, the Soviet Union's second largest city, and threatened Moscow itself. The war ended for the Soviet Union on 9th May 1945.5 Sovkhoz

state-run agricultural enterprise. The first sovkhoz yards were created in the USSR in 1918. According to the law the sovkhoz property was owned by the state, but it was assigned to the sovkhoz which handled it based on the right of business maintenance.6 Pushkin, Alexandr (1799-1837): Russian poet and prose writer, among the foremost figures in Russian literature. Pushkin established the modern poetic language of Russia, using Russian history for the basis of many of his works. His masterpiece is Eugene Onegin, a novel in verse about mutually rejected love. The work also contains witty and perceptive descriptions of Russian society of the period. Pushkin died in a duel.