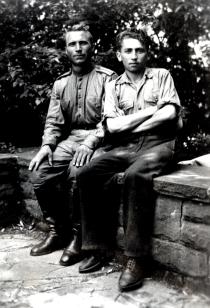

This is a photo of me during my service in the army. I was senior telephone operator of the training battery of an artillery regiment. I sent this photo home in Kiev. Panevejis, 1941.

In 1941 I worked as a tutor at the children's tuberculosis recreation center in Budayevka. I was there when the Great Patriotic War began. I was mobilized on 11 July 1941, when German troops were approaching Kiev. Our district military registry office formed a unit and we marched in civilian clothes to the east. Then we came to Mariupol [700 km east of Kiev] by train, to a camp from where we were to be sent to the front. From Mariupol we went to cossack camps near Kherson in 750 km from Kiev. On 3 September in the morning our commander ordered us to line up and said: 'It is our task to throw Germans out of Kakhovka'. We marched there day and night. On 8 September at 11 o'clock commander of the regiment called me. I was beside my battalion commander in a trench. It was quiet and I heard the voice of our regiment commander on the phone: 'The division and regiment are retreating. Your task is to back up their retreat'. The battalion commander said to me: 'Not a word about it!' He was a brave man, a real commander. He realized that we might get in encirclement. On the night of 9 September we were trying hard to hold on in the bare Pridneprovskaya steppe in 40 km from Kakhovka (450 km from Kiev). The only weapons we had were rifles and grenades. There were Germans on our left and right, driving on trucks and marching. We had small digging tools and the soil was dry and it was hard to dig trenches under the enemy firing.

About 4 o'clock in the afternoon Germans troops began to fire from mining units and a huge mine exploded nearby. I was deafened for the time being, but I didn't faint. All of a sudden I heard my commander saying: 'That's it, guys'. I couldn't believe what I heard. He didn't kill himself. He believed that we had completed our task, that we backed up their retreat and self-annihilation that military order required from us was not soldiers' business. He was the first to get up and raise his hands when our platoon was encircled. I saw 6 of us standing with their hands up.

A few minutes later Germans told us to move on and we covered 500-600 meters where other prisoners gathered. I thought I was living the last minutes of my life and that I would never see the sun again. I was a Jew. I was only 20. I didn't want to die. An interpreter ordered our commander to line us up in two lines. A car stopped in front of our line. There was a German officer standing in it. He said in distorted Russian that from then on we were to serve the great Germany honestly. After this speech he gave an order: 'Zhydy [kikes] and communists - 2 steps ahead!' The only communist among us was Davydenko, commander of a communication platoon, but nobody betrayed him or us, three Jews. Beikelman stepped ahead by himself. He didn't hope to survive with his strong Jewish accent. There were 6-7 prisoners who stepped ahead of the line. They were taken away and nobody ever saw them again. There were 8 or 9 other checks, but nobody gave me away.