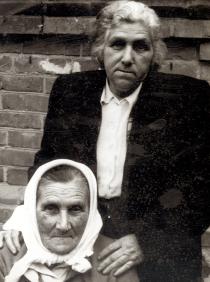

This picture shows my father, sitting in front and my cousin Arkadiy, the son of my mom’s sister Vera, in the back. It was taken one summer in the 1950s in Vinnitsa.

One of our friends took the picture, father put on a suit and a hat for the event. Usually he dressed more modestly.

When Arkadiy was a young man he imigrated to Israel. Now he lives there with his wife and two daughters. I remember him being a very decent person.

My father, Boris Elyukimovich Khapun [born in 1898], was the youngest in the family, ninth or eleventh. As a child my father studied in cheder for two or three years; he did not study anywhere else. He was proposed for some courses later on.

Since everyone in the family was a blacksmith, my father also became a blacksmith; it was inevitable. Father didn't shoe horses.

Plants were constructed and developed in Vinnitsa at that time [1910-1920s], and various specialists were in demand. Father went to a plant and worked there as a blacksmith.

Father was taken to the army during the Imperialistic War [WWI]. He didn't want to go to war, but he was a healthy man. However, the conditions were such, that one wasn't accepted to the army in case of absence of teeth. So father went to the dentist and pulled out healthy teeth without anesthesia. But after he had pulled out his teeth, he was nonetheless enrolled for the army.

He served in the infantry under Kerensky. He had a picture of himself: so slender, with shoulder straps and a red bow on his chest. The Revolution had already begun, and those who were supporting it wore bows. The Jews were suppressed under the tsar, but Kerensky abolished all prohibitions, the Jewish pale, for instance. That's why father supported him.

When my father was in evacuation, he worked at a plant. Every time they came to mobilize, father was not touched; no one could imagine that the plant management would send him away. Father worked until he fell ill.

When he became very weak, he asked my friend, the manager of a park, if he could work at the attractions, because they also came out of order.

The manager said, 'He's an old man, why does he want to do that?' I told my father, 'You have a pension, I'll give you money, get some rest, why work?'

This was exactly what disappointed him. He didn't reply but I knew that he was displeased.

Father continued to live in Vinnitsa, where he died in 1970.