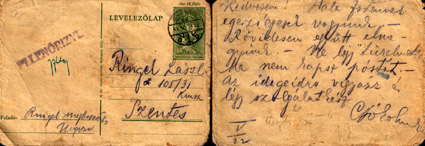

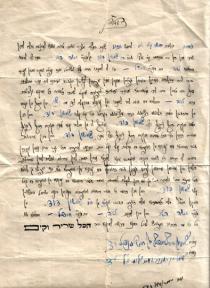

This is the card that I received from my father Mor Ringel when I was in the Hungarian Labor Battaliaon in Szentes. It was written in Uzhgorod on 22 May 1944. There is a military censorship stamp on the card. Sender: Ringel Mor, Ungvar. Addressee: Ringel Laszlo z.105/31, Szentes. The text: My dear, thank God, we are in good health. Soon we shall leave together. Don't worry that there will be no letters from us. Watch your nerves and be industrious. Kisses. 22 May 1944.

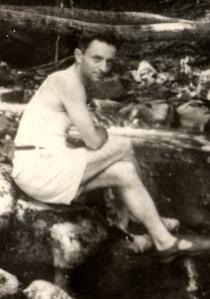

I was recruited to the army in 1938. The military commission sent me to a field engineering battalion where I served half a year. We were trained to build pontoon bridges, studied blasting, search and removal of mines on an island on the Danube near Budapest. After the law on work battalions was issued all Jews from 4 field engineering battalions were gathered in one battalion that they called a forced labor battalion. A Hungarian officer became its commander. We wore soldiers’ uniforms, but had yellow armbands on our sleeves. In 1942 we were moved to Ukraine to dig trenches near the front line and removed mines. We kept moving from one place to another. In 1943 Soviet troops began an attack and we were taken to Romania to build fortifications on the border and shelters in the mountains. [He probably refers to Northern Transylvania, that is a part of Romania now but was a part of Hungary during those times.] Later we moved to work on a railroad construction. We installed 40 km of the rail track in Northern Transylvania. From there we moved back to Subcarpathia, to the village of Volovets [70 km from Uzhgorod, 600 km from Kiev], in the Carpathian Mountains where we built bunkers and fortifications in the mountains. I was fortunate to have leaned the blacksmith’s work in the shop in Budapest. I was sent to work in the repair shop where we fixed spades, picks and other tools. In spring 1944 commanding officer of our battalion received a telegram from his commanders that our battalion was to be transferred to Hungary, Szerencs town. We went there by train. At that time they began to send Jews to ghettos.

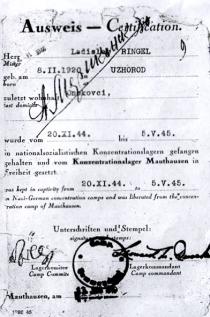

I corresponded with my family. From the last card I received from my father I knew that Jews of Uzhgorod had also been taken to the ghetto. I went to Uzhgorod. The train went as far as Chop [25 km from Uzhgorod, 690 km from Kiev], and I walked about 20 km. In Uzhgorod I was told that the ghetto was in the former brick factory. At quite a distance from the ghetto I heard the buzz of human voices like bees in a beehive. The Hungarian guards didn’t allow me to go in there, but they called my mother, my father and sister to the fence. The fence was made from bricks in chess order with openings trough which we talked. My father tried to give me a letter through the opening, but the gendarme watching us took it away. This was the last time I saw them. When I returned to Szentes I received a card from my father where he wrote that the following day all Jews were to be taken away from the ghetto. He asked me not to worry. I never heard from them again. After WWII my acquaintances returning home from concentration camps told me that right upon arrival to Auschwitz my father was taken to a gas chamber. My mother looked young for her age. She and my sister were taken to a work camp in Stutthof on the Oder on the Polish-German border. [Stutthof is on the Vistula, near Gdansk.] People who returned from there said there were shootings and bombings and they didn’t know for sure how my mother and sister perished. They worked in the woods, on wood processing sites, in this camp. Since winter 1945 Soviet Air Forces were continuously bombing this camp. Many inmates perished then.