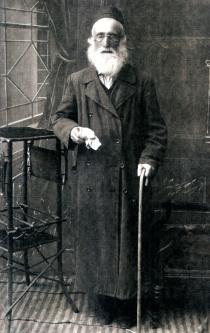

My husband Natan Gornshtein on a photo taken in 1992 at home in Chernovtsy.

I married him in 1956. He was a Jew born in Odessa in 1926. With his fair hair and gray eyes he didn't look like a Jew. Natan graduated from the Railroad College and got a job assignment at the railcar depot in Chernovtsy. His mother's sister was living here. For a few years, Natan served in the army in the Far East, where people had no idea about what Jews were like. He never heard Yiddish and when he came to Chernovtsy he was surprised to hear Yiddish spoken in the street. Out of about about 150,000 people in Chernovtsy, 60% were Jews. He liked it so much there that he requested to be sent to Chernovtsy after finishing college. The reason he gave was that he had a fiancée in Chernovtsy. His words proved true. I had a friend who lived in the same building as his aunt. Once, his aunt mentioned to my friend that her nephew was visiting her and that it would be good if he met a nice girl. This friend of mine introduced us to each other in March. We courted for half a year and got married in September. His mother's name was Hana, the same as mine. Somebody told her that it was against Jewish tradition for a mother-in-law and a daughter-in-law to have the same name. She said: 'My son wants to marry her. And if something bad were to happen, let it happen to me.' We didn't have a Jewish wedding. Mama made dinner for the family and close friends. My husband moved in with us. Mama and I spoke Yiddish, and he learned the language during those years. Some time later he entered the University of Railroad Transport Engineers.

We continued celebrating the Jewish holidays in our family. We celebrated Pesach according to the tradition. We bought matzah, made stuffed fish and baked cakes. My daughter Polina cooks this traditional food now. My husband came to like these holidays. I have fasted at Yom Kippur since I was 11, and Natan joined me. Polina speaks Yiddish and Hebrew. As for Marina, I don't think she knew any Hebrew before she left. We also celebrated Soviet holidays. We enjoyed cooking a nice dinner for the family and having guests. We didn't care much about the meaning of these holidays.

From the 1950s through the late 1980s anti-Semitism was on the rise at the state level in Chernovtsy, as well as in the rest of Ukraine. It was mainly demonstrated during admission to the higher educational institutions. I will give you an example with the Medical Academy. If they admitted about 300 students per year, there could be only 2-3 Jews among them. Just because they were Jews these young people were not allowed access to higher education. Our children went to other cities, mainly in Russia and the Baltic republics, where anti-Semitism was not so strong.

In the 1970s Jewish people began to move to Israel. We sympathized with those who were leaving, and were a little bit jealous. Regretfully, our family couldn't leave. One had to pay for one's diploma at that time before moving, and we didn't have that much money. The authorities justified this requirement with the fact that the state had spent money to give us an education, so we were obliged to compensate it for the costs. My husband and I, my sister and her husband had diplomas, and the amount we were supposed to pay was far above what we could afford. We were eager to go to Israel, all of us, but our financial problems were an obstacle. When Ukraine declared its independence in 1990, we started planning to move to Israel again, but my sister fell ill with cancer. She needed help and I could not leave her when she was so ill. My sister died in 1990. Two or three years later my husband fell severely ill. We stayed. My husband died in 1997 after several surgeries. He was a wonderful man, husband and father. I shall never recover from losing my sister and my husband.