These are my maternal grandparents: Ester Fejga (first row, first from left) and Benjamin Menczer (first row, second from left) with their children and grandchildren. I’m not able to recognize all. I’m standing in third row in center, my mother - Gitel in second row, as a second from left, her brother and my uncle - Fajbisz in second row, as a first from right. The photo was taken in Mielnica Podolska in 1933. Dawid Szternberg took it.

The oldest memories I have is the fire at our neighbor's house. It was 1927, I wasn't even four. Grandma Steilberg, my Grandpa's Benjamin Menczer, my mother's father’s sister lived there. I only knew my maternal grandparents. Because Father was, say, acquired to the town from Kolomyja, next to Stanislawow.

My maternal grandma, Ester Fejga Menczer was of middle height and rather hefty, right. She didn't wear a wig. Her hair was red but already grizzled. We'd lived at Grandpa and Grandma's Menczer before I went to school. When we lived with them there were four of us children in the household and Grandma had to take care of us all. I think it was Grandma who spent most time with us, she was our superior. She had to urge us to eat. Besides, she was in very firm close relations with us, we had a strong family bond. She died in 1936 or 1937. It was extensive pneumonia. She didn't suffer too long. I remember that day. It was fall. Grandma died on Friday afternoon. The Sabbath had already begun. She had to lay in bed all through Saturday because it was not allowed to move her! The funeral took place on Saturday evening. As soon as the Sabbath was over the procession set off. I remember the mourning at home. It lasts seven days, you sit home, on little benches, right, barefoot. Grandpa sat there, and his son Fajbisz Menczer, who was still a bachelor at the time. I don't think Dad prayed with them. No, because he had to be at the shop at 5 a.m., do things. They didn't shave. Grandpa was carrying the water out from the house. They didn't smoke - Grandpa was a smoker - and [they sat] in socks, without shoes. I don't know why it was that way. Well, it was such tradition. Apart from that, my uncle Fajbisz Menczer, Grandpa's son, used to go to the synagogue for the service everyday for the next year, to recite Kaddish. There were no prayers at home. I don't remember any.

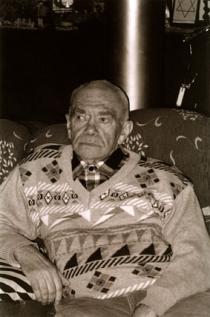

Grandpa Benjamin Menczer, was a tall, handsome man. And healthy, too. He had a beard. Well, every elderly man there in the town had a beard anyway. He was not a stern man. He was very kind-hearted towards Mom, his daughter Gitla Menczer and his son Fajbisz Menczer, too, and his grandchildren. I remember going with Grandpa to swim in the river Dnepr. Just the two of us. It was in the summer, we would head out at daybreak. We would make the trip two, three times during the summer. It was rather far off. The gorge was very deep, you had to have some [strength] to climb down and up again. Well, I had already had my bar mitzvah at the time. I was 13. Jews have their mikves and maybe he thought the swimming passed for bathing in a mikveh, it was running water, right. Well, but I'm not that sure.

Right after getting married my parents moved into Grandpa's house. Because they didn't have their own house yet. Until 1936 we lived at Grandpa Benjamin's Menczer, Mom's father's, next to the market square. In 1935 and 1936 - I was 11 - Father built a new house and we moved in there. The house was a couple of blocks away from the market square. The constructing works didn't last long, it took one year, or one season maybe, I don't remember exactly. Father amassed enough money, he'd been saving, right. I guess we were doing rather well. It was a beautiful, large house and it cost a lot of money. Modern, wonderfully arranged. You could tell it just from looking at the triple windows. At first it was all, the whole house was ours. There were two rooms upstairs, so my sisters got one and I got the other little one, and there were spacious rooms downstairs. There were five rooms and a kitchen. Beautifully furnished. Floor parqueted with one-meter-long boards, in squares. Coal stoves, electric light. I remember a rabbi once paid us a visit. It was a rabbi from Father's homeland, from Kolomyya, and apparently Father invited him over to bless the house.

I remember the prayers at home. And lots of guests came. Father apparently invited them.

Grandpa ran a pub at home, and Grandma Ester ran the kitchen, for the guests, right. That was how they made their living. The pub occupied part of the house, in a big hall. You could eat there, drink and sleep over. Grandma took care of it all. The pub was a rather crude place, I'm not sure how to put it, but a rather simple one. There was one long table and three or four smaller ones on the other side. No big parties there, they were rather focusing on the market days, the fairs. The Ukrainian peasants would come to have a cup of tea, or some beer, or a shot of vodka, to eat something, to snack. The pub was in a very good spot, right next to the market square. I'm sure it wasn't kosher so Jews didn't have any use of it. A Jew might have come by once in a while to have a beer but the place was generally for the non-Jewish.

Grandma had four, maybe six beds at her disposal. Meaning there was a separate room for the guests. You had to cross the pub to get there. More or less twice a week people would come to the town from wholesalers, from various cities, middlemen between the wholesalers and the stores. Travelling salesmen. They usually stayed in town for a day or two. They collected their orders from the stores, and they needed a place to sleep. Grandma would make them dinner and offer them a bed. I don't know if it was official, legal, or just like that, but I'm sure the pub itself was legal. There weren't too many pubs like that in the town, only some little cafés, but those were rather for the Jews, right. The cafés were rather fancy social places. Only the socialites sat there. The well-read, the cultured ones. Well, and not everyone in the town was so exclusive socially prominent, so to speak. For most of the Jews religion was the center of their lives, they wore payes. The Jewish schoolboys also had payes, right. I remember Grandpa's pub was doing pretty well. Well, you could see a decent crowd sipping their beers. There even was a beer pourer. The keg was in the basement. Those were wooden kegs. And they were connected, right, with a rubber pipe to the tap in the pub. Upstairs at the bar there was this hand pump that filled the keg with air and the compressed air pushed the beer up. When you opened the tap the bubbly beer would flow, already with a head. A very common device those days.

There was also a store in Grandpa's house. My father ran it. Grandpa asigned a nook of his house as the store, right. It was a long store. The width was maybe 4m and the length could be 7m, more or less. Well, you could find there groceries, exotic spices, some industrial goods, and what not. You know, you could buy a penknife by my father's, or a pair of stockings. Well, all the everyday, little town stuff, right. As for the groceries, father was supplied by a wholesaler, there was a local one. And it was a Jewish wholesaler. As for other things, the salesmen came to town every other week.

Apart from that Grandpa Benjamin and my father also had some fields. They didn't farm them by themselves, the land was located 6 or 7 kilometers from the town, in Kudrynce near the Russian border. It couldn't have been large. I don't know how did they end up owning it. It could have been some old affair. I just remember the balk of, I think, Father's field was lined with walnut trees. They bore beautiful walnuts.

The Jewish tradition was thoroughly observed at Grandma and Grandpa Menczer's home. I need to stress it. Traditional in 200 per cent, you could say. Grandpa used to go to the synagogue three times a week. When he wasn't praying at the synagogue he sometimes prayed at home with his son Fajbisz. As for Daddy, I don't think he prayed everyday. He had to be in the store at 5 a.m. sharp, prepare things. Grandma cooked kosher. Her meals were nothing special. And our meals at home neither. You know, ordinary Jewish food, like in every Jewish home. We always had a chicken on Saturday. Besides, those were the Borderlands, there were lots of corn, lots of mamalyga. Corn flour mamalyga and malayes, right. Those were the staples. Mamaliga is a boiled corn flour, and malayes are the same only baked in the oven. They were sometimes spread with cherries. That was one of the simpler, primitive dishes. We also had some more interesting ones on festivals. Well, I can't tell exactly right now but there were those apple pies, and we had them quite often. And the fludn. Der fludn in Yiddish, a very heavy cake, with nuts, very thick. Well, it was all very tasty. We could afford it and we indulged in it. Oh, and we drank whale oil everyday. It was a must. Mommy watched that we drank it.

The Sabbath looked quite ordinarily at our home. Well, the stores in the town were closed during Sabbath. Father would go to the synagogue, right. Mom would lit a candle in the evening, there would be prayers before the supper, blessing the bread, right. It looked like that when we lived at Grandpa's, but when we moved to our own house we still went to the synagogue, without question. But as long as we lived with Grandpa the Sabbath evening was more ceremonial. And the candles were lit for a longer time, right. All the recommended prayers, everything was done in a more solemn way. When we lived by ourselves Mom lit the candles, we came back home from the synagogue, but it was not as cermonial as at Grandpa's. It wasn't stressed that much. But we always kept kosher. I went to a Hebrew school, to the synagogue, so I knew about those things. I spoke Hebrew, I've had a bar mitzvah. It was very ceremonial but not at home. In the year following my bar mitzvah I had to regularly pray at the synagogue. Later it was not so regularly. Checkered, I'd say.

We spoke Yiddish at home so I'm not really sure how and when I've learned Polish. Well, it was broken Polish at first, a mixture of Polish and Yiddish with the Ukrainian lilt. My command of the language has developed gradually but I can't precisely describe how and when. Besides, we had various of various ethnicities neighbors. For example our closest neighbor was the school's principal. A Pole. He often invited us, the children over. We helped him out, raked over his garden a little, right. Well, I have somehow learned Polish. I do speak it.

After the World War II I came back to my town, to Mielnica Podolska. Everybody headed for their hometown. So did I. But I already knew nobody was there. In the summer of 1945 I wrote to my town, to the town council, or sovyet. It turned out they gave my letter to Dawid Szternberg who had stayed in Mielnica. He and his sister survived. Had anyone else survived? No. Just the two of them. And so I got a letter from him saying my family was all gone. There was nothing in it about the circumstances of their deaths. They had all been killed, that was all. When I got there the townspeople told me all the Jews had been deported to Borszczow by the Germans on one summer day in 1942. They made them walk the 20 kilometers to Borszczow. A ghetto was created there for the Jews from all the surrounding towns. They kept them for a week or two, hungry and cold, and later herded them into railcars and sent to a death camp somewhere The Jews were probably deported to Terezin, as Borszczow was located 1.5 km away from a railway station on the Terezin-Iwanie Puste line. I've never been to Borszczow. I don't know the town. Besides, Dawid knew everyone was dead. They were gone from Mielnica without a trace.