Ida Limonova

Kiev

Ukraine

Interviewer: Inna Zlotnik

Date of Interview: August 2002

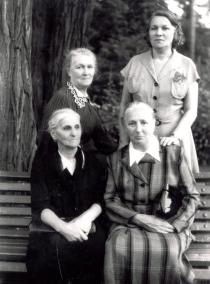

Ida Limonova lives in a one-bedroom apartment in the Syrets neighborhood. Ida lives alone. She does her own shopping and cooking. She has lunch in Hesed twice a week. I expected to see a frail elderly woman and was amazed to be met by a tall slender gray-eyed woman with dark curly hair. She was dressed tastefully in a white blouse, beige skirt and a sleeveless jacket. She was wearing a brooch. There is not too much furniture in her room: an old sofa, covered with a checkered blanket, a wardrobe, a folding bed, a side table, two arm-chairs and a TV set. There is a big bookshelf on the wall. Ida said that it was made by her father. She has books by Jewish writers such as Sholem Aleichem, David Gofstein, Itsik Feffer, Efraim Sevella, and Russian and Ukrainian classics. There were also photographs of her family. There were books on the side table, too: poems by Peretz Markish and detective stories by Boris Akunin. Ida reads a lot, follows world news and often goes to Hesed. Ida was very pleased to give this interview and leave her memories to her sons, grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

My grandfather on my father’s side, Moshe-Aren Sneiderman, was born in the town of Mitava in Kurlandia province, Latvia, in the 1850s. It was part of the Russian Empire, and Jews had the right to reside there and do their business: commerce, crafts, and so on. They were different Jews in Kurlandia: they were townspeople, wealthy and well educated. Most Jewish families in other parts within the Pale of Settlement 1 in tsarist Russia grew their own vegetables and kept livestock while Jewish families in Kurlandia were drawn towards a European lifestyle. They spoke the so-called Kurlandia Yiddish, which was their own dialect.

My grandfather was a tinsmith, and also sold food products. My grandfather was a big man with a gray beard. He always wore a yarmulka. Unfortunately, I don’t know anything about his life in Kurlandia except that his family was wealthy and respectable.

My grandfather’s wife, Rodoneha Sneiderman, was also born in the town of Mitava. She was ten years younger than my grandfather. My grandmother was a housewife. They had nine children. My father had three brothers, Pinhus, Abram and Emil; and five sisters, Dina, Ida, Lida, Bertha and Hava.

At the beginning of the 20th century my grandparents and their family moved to Kharkov. I don’t know why they decided to move. We had a pre-revolutionary picture of my grandmother. Her attire shows that hers was a wealthy family. She had a beautiful blouse, a chain watch and a beautiful hairdo. It was a custom among Jewish women to wear wigs at that time, so I guess, it was a wig. My grandmother always wore a long skirt and a blouse. She was a reserved and calm woman. My grandparents were religious. They always fasted on Yom Kippur, celebrated Rosh Hashanah, Sukkot, Chanukkah, Purim and Pesach. I sometimes visited them on the eve of Sabbath. On Friday evening my grandmother lit candles and said a prayer. They followed the kashrut. She even had a special cloth for washing kitchen utensils for meat and dairy products. My grandfather was confined to bed from the early 1920s, and my father looked after him. He died in 1926, my grandmother died six years later.

My father, Vladimir Sneiderman, was born in Mitava in 1884. He was the first baby in the family. He studied at cheder, but he was very intelligent and very handy with things. He was very strong and healthy. After the family moved to Kharkov he found a job as a locksmith at the locomotive repair plant. He also had a good ear for music and soon began to play in the brass orchestra of the plant.

My father’s sisters and brothers were also born in the town of Mitava. I don’t remember very much about them. All boys in the family finished cheder; the girls were educated at home. My father’s brothers and sisters weren’t religious.

His brother Pinhus, who was two years younger than my father, owned a hardware store in Kharkov. He had a wife called Leya and two sons: Mosey and Aron.

His sister Dina, born in 1988, was a housewife. Her husband’s name was Haim. They had a daughter, Sima and a son, Yankel. Dina knew many Jewish songs. I don’t know where she learned them, but she often hummed all kinds of tunes. My father’s brother Abram was three years younger than Dina. He was a bookbinder. He was married but had no children.

Ida and Lida were born in the early 1890s. Ida was an assistant accountant at the electromechanical plant. She had a husband called Joseph and a daughter, Rita. Lida was a housewife. Her husband Aron perished in the Civil War. Lida was raising her son Jacob and had to earn a living. She sewed to earn some money.

My father’s brother Emil, born in 1898, was a typesetter at a printing house in Kharkov. He was fond of singing. My father’s sister Bertha, born in 1900, got married in the 1920s and moved to Tula with her husband Mikhel. That’s all I know about them. My father’s youngest sister Hava, born in 1903, married a student from the Medical College, Abram Levenberg. He became a dentist. She was a housewife. They had three children: Fira, Anna and Gregory.

My grandfather on my mother’s side, Abram Gelbartovich, was born in Poland in the 1860s. Jews had the right to live in Poland, the right of land ownership and equal rights with Christians to stand in court. Jews played an important role in banking, trade and industrial business. My grandfather was a representative of the Singer Sewing Machines Company.

My grandmother, Leya Gelbartovich, was born in Poland in 1865. She was a housewife and and she took care of their eight children. I don’t remember my grandmother. She was very sickly and died in 1917 when I turned 3. In the late 1880s my grandparents and their first-born son Ekhil moved to Kharkov due to growing anti-Semitism in Poland and the polonization of industry and commerce.

My grandfather was religious. We even had the five books of Moses, the Torah, at home. My grandfather used to read it. He had many prayer books and always put on his tallit and tefillin. He prayed twice a day: in the morning and in the evening. It was a sacred process and nobody dared to interfere. My grandfather was a gabbai in the Chebotarskaya synagogue in Kharkov. He was a very respectable man, and people always came to ask his advice regarding family life, bringing up children, and so on. He had a big gray beard, was a handsome, stately man, and when he came back from the synagogue he walked into his yard with his hands on his back. At the same time he only had one suit, but he managed to wear it with an air of dignity. My grandfather liked to play with us. I don’t remember him telling us any stories from the Talmud or the Bible.

My mother, Rosalia Sneiderman [nee Gelbartovich], was born in Kharkov in 1888. Kharkov was a big industrial, commercial and financial center. Jews held key positions in the finances, in trade, medicine and publishing. New synagogues were built at the beginning of the 20th century; the biggest one of them was the choral synagogue.

My mother’s sisters and brothers were all born in Kharkov except for her oldest brother Ekhil, who was born in Poland. He studied at cheder and lived in Kharkov for some time. During the Russian-Japanese war [1904-1905] he was at the front. He returned from the war as a grown-up man. He had a beautiful uniform: a dark jacket with shining buttons, a buckle on his belt with a double eagle, a cap with a cockade and shoulder straps. Later Ekhil worked as a locksmith. His wife's name was Liya. They had a son called Abram. During World War II he was in evacuation in Saratov. His son Abram and his family live in Chicago, USA, now.

The second child was Naum, born in Kharkov in 1883. He only studied at cheder. He was a tall and stately man and wore glasses. He worked as a writing clerk in offices. He was sickly and didn’t live long. He had nerve problems. His wife‘s name was Rosa Burshtein. Their daughter Ira got a higher education and became a doctor. She lives in Los Angeles, USA, now.

My mother’s brother Mosey, born in 1886, lived a long life. He also just studied at cheder. He was married, but I don’t remember his wife’s name. He was in evacuation during the war. He died in the 1950s in Kharkov, and his wife died even before that. They had no children.

My mother’s youngest brother, Mikhel, was born in 1897. He was a very interesting man and we were very good friends with him. He ran away to join the army when he was a boy. He took part in the revolution of 1917 and the Civil War. Later he became a professional military. I don’t know what his rank was, though. Like all military man he served in many towns of the Soviet Union. In 1937 he visited Kiev and stayed with me. We were glad to see each other. Shortly afterwards he was arrested [during the so-called Great Terror] 2 and executed. He was married. He didn’t have any children with his wife but he had an illegitimate child, Lilia. I didn’t know her.

My mother also had three sisters: Manya, born 1891, Nyunia, born in 1894 and Zoya, the youngest one, born in 1899. My mother finished elementary school. She was very fond of reading. Manya, Nyunia and Zoya finished grammar school.

Manya was an accountant, and Zoya worked at a state bank from the 1930s. In the beginning she worked in Kharkov. Later, when the capital was transferred from Kharkov to Kiev, she and her husband, Isaac Fidelev, who worked at the bank as well, moved to Kiev. I was very glad that I had relatives in Kiev, because the rest of my family was living in Kharkov. My parents, their brothers and sisters and both my grandfathers were there.

My mother’s brothers and sisters weren’t religious. They spoke Russian, although Yiddish was their mother tongue. I believe they might have observed some Jewish traditions to pay their respects to their parents and the past of their people.

My parents met in Kharkov. My father was playing at a wedding and the bridegroom was my mother’s friend. My father talked with my mother a little. They got married in Kharkov in 1908. They had a chuppah and my father’s friends played music at the wedding. The newly-weds lived with my mother’s parents. My father worked as a locksmith and played in a brass band; my mother helped my grandmother about the house.

In 1910 my older brother, Izia Sneiderman, was born; I followed on 26th August 1914. Shortly before, on 1st August, World War I began. [Editor’s note: The war actually began with the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy’s declaration of war on Serbia on 28th July. After that Russia ordered mobilization of her forces, and, on 1st August Germany declared war.] My father went to the front. After the revolution of 1917 my father volunteered to the Red Army and served in Kharkov in a music band until 1924. My father played the horn very well.

My father quit the Red Army in 1921 and from then on played in brass bands. He performed at parties and weddings and often brought me along. He also took me to parades. The biggest parades were held on 7th November [on the so-called October Revolution Day] 3 and on 1st May. We sang and danced at parades. I can hardly hold back the tears in my eyes when I hear a brass band playing. I recall my father and the old times and my childhood. I love listening to brass bands.

My brother Izia studied at a Jewish school that was located far from our home. This school was called Tarbut 4. They studied all subjects in Hebrew. My brother studied old Jewish songs at home, and we often sang them together.

We always celebrated Jewish holidays at home: Pesach, Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, Chanukkah, Purim and Sukkot. I have the brightest memories of Pesach. There was always a general clean-up on the eve of Pesach: things were washed, cleaned and koshered. All kitchen utensils were rinsed with boiling water and there was a big stone in the washing bowl, perhaps, for keeping water hot for longer. We also had special dishes for Pesach. Our dinner table was covered with a special starched snow-white tablecloth. There was stuffed fish on the table and tsibele – hard boiled eggs cut with onions. There was also chicken on the table. Our family got together at the table.

My father used to make red wine that we had on holidays. Long before Pesach he bought dark raisins for the wine. There was one special beautiful wineglass set aside for Elijah ha-nevi. My grandfather was the master of ceremony at the table. He said the prayers. I was sitting to his right. On his left there was a chair with two pillows on it and two or three pieces of matzah underneath called afikoman. The afikoman is the last piece of food eaten at seder. The word afikoman is the Hebrew form of the Greek epikomion, which means dessert. It’s a tradition to hide the afikoman for the children to find and to ‘negotiate’ for its return. The seder cannot be concluded until the afikoman is redeemed. I was supposed to steal these pieces of matzah without my grandfather noticing it. Of course, my grandfather pretended that he didn’t hear or see me doing it, and when I got the matzah everyone at the table complimented me on my smartness. My grandfather always said a prayer, but I don’t know what kind of prayer it was.

My mother made pastries on holidays. She made flour from matzah and baked teyglakh from this flour: these were little pellets from flour and eggs boiled in honey, pressed on a board and cut in slices. They were also sprinkled with nuts and ginger.

At Chanukkah we had a silver chanukkiyah hung on the wall. It had eight holes for oil and wicks in each hole. Every day one more wick was lit. Kids got Chanukkah gelt, traditionally given as a Chanukkah gift and used for the dreidel game. We also celebrated Rosh Hashanah with apples and honey. Yom Kippur was the most important holiday. My grandfather and my mother fasted and prayed. My brother and I didn’t have to fast when we were small.

There was Sukkot. A sukkah was made, and people had their meals and celebrated the holiday in their own succah. We also celebrated Simchat Torah – a holiday marking the conclusion of the annual cycle of Torah readings and the beginning of the new cycle – the final fall holiday. We celebrated Purim. I remember the delicious hamantashen and strudels with poppy seeds – I still find those more delicious than any other cakes. My mother told me that she had seen Purimshpils before, but at my time there were no such performances.

I also attended a Jewish wedding party. It was the wedding of my Aunt Hava, my father’s younger sister. The bridegroom was Abram Levenberg. I was wearing a dark gown with a white collar. The bride and bridegroom had a chuppah set up at the synagogue. The most distinctive feature of any Jewish wedding is the chuppah. This term is taken from the Talmudic stipulation that a marriage doesn’t take legal effect until the bride has entered the chuppah. It’s a canopy-like structure consisting of a piece of cloth, that is held aloft on four posts, and beneath which the couple stand during the religious wedding ceremony. The rabbi said a prayer and the bride and bridegroom exchanged wedding rings. The bride was wearing a silk dress and had a shawl on her head. The bridegroom was wearing a shirt – there were no suits with jackets at that time – they only came into fashion in the early 1930s.

When my grandfather was still alive our family was trying to follow the kashrut. Only my father secretly broke the rules: he liked pork and sausage. He ate these at other places than home because he respected my grandfather and didn’t want to hurt his feelings.

My mother was a housewife and took care of the children. She also cooked meals for students. There was an institute not far from our house and students came to buy an inexpensive and delicious homemade meal. I believe this was kosher food, because this was the only way all food was cooked in our house. My mother also did some sewing to make some extra money. She did this when the family needed it badly. When my father could provide for the family she returned to her housekeeping duties.

We had an apartment in Kharkov, not far from the city center. Our house was the last building in this lane and was located on the bank of the Lopan River. There was a bridge across the river connecting our lane and Klochkovskaya Street with the big Blagoveschenskiy food market in it.

Our family lived in a two-bedroom apartment on the first floor of one of the three two-storied red brick buildings in our neighborhood. We had running water at home, but the toilet was in the yard. There was a big yard where children from these three buildings played. Our rooms were furnished poorly: a table in the middle of the room, a sofa and a bed. My brother slept on the sofa, and I slept in the bed. My grandfather slept in the kitchen and my parents had a small bedroom with a wardrobe, two beds, a big box, my mother’s Singer sewing machine and a dressing table. It was very cold in this apartment in winter. It was heated by a stove. There was a sawmill near our house. We took two bags of sawdust from there every day to heat the apartment. I remember my grandfather sitting at the table in the kitchen wrapped in my mother’s woolen blanket, reading a book. He was constantly reading, only he didn’t remember what he had read. He was an old man and his memory was fading. He could only remember very little.

My father was a very smart man. Once, when I was chatting and chatting, he stopped me and asked whether I knew the difference between a smart person and a fool. I began to think and he said, ‘A fool says all he knows and a smart person knows what he says’. When I was 17 I had a very important secret and wanted to share it with my father. Before talking to him I asked him if he could keep a secret. My father smiled and said, ‘If you can’t keep your own secret how do you think another person can keep it? Remember this’. And I always remembered it. My father was very skilled. When I was 8 he made me a doll’s cupboard (about half a meter high and 40 cm wide). It was a very beautiful cupboard and all our neighbors came to look at it.

There were Ukrainians, Russians and quite a few Jewish families in our neighborhood. I remember a shoemaker called Rabinovich. His family lived in the basement of our house. Some craftsmen from our neighborhood made a swing and installed it in our yard.

There was a synagogue in our neighborhood. I used to go to there every now and then. I don’t remember my father going to the synagogue. There were two floors in it: the lower floor for men to pray and the upper floor for women. My mother went to the synagogue on Pesach, Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, Chanukkah and Purim. She took me with her and we stayed on the second floor. My mother had a Yiddish prayer book with her. Most of the time she wore a blouse, a skirt and a hat on holidays. On weekdays she usually wore a kerchief. My mother was a beautiful woman. On bigger holidays there were cantors singing at this synagogue. One of them was called Shteinberg. He was a young man and he toured with a boys’ choir. The boys had beautiful voices. Most of them came from poor provincial families and their parents were glad that their children got all necessary provisions and food from the choir organization.

I went to a Russian secondary school because Jewish schools were all closed in the late 1920s. The school I went to was in a one-bedroom apartment. There were very few children that formed 5 classes and there was only one teacher. All children were sitting in one room and the teacher went from one group of children to the other handing out exercises. The school was soon closed and I went to another school, rather far from our home. There was an Armenian school on the first floor, and we studied on the second floor at a lower secondary school [7 years of studies]. We studied mathematics, physics, Russian, history, geography and botany. In 1924 I became a pioneer. My parents didn’t mind me becoming a pioneer, but my grandfather was upset that I wouldn’t be able to attend the synagogue any longer. We continued to celebrate all Jewish holidays at home. On the day when Lenin died in 1924 the inhabitants of our lane went to the bridge next to our apartment. People were crying and talking to each other about the future.

In 1925 we moved to another apartment. There was a living room in this apartment where I also slept, my parents’ bedroom; and my grandfather and Izia had small rooms of their own. There were four apartments in this house. There was another Jewish family living in the house, a Russian family and our landlord, Gregory Bagancha, a Ukrainian. My father and he were good friends. My father gave him a hand with all his construction projects: he helped him to make a verandah for example. Gregory was married, but he didn’t have children. They invited our family to join them for Christian holidays: Christmas, St. Trinity Day, and so on. They weren’t religious, but they celebrated these holidays as a tribute to old tradition. They made all kinds of traditional food and we celebrated enjoying the company and the food. I went to the 5th grade at the Russian school near our new home. This school was an old two-storied building. It had a canteen where children were shop assistants and each of us waited for his turn to sell cookies, candy and stationery.

There was also a pioneer center housed by an old two-storied building. There was a stage and a hall with seats. We performed concerts singing pioneer and revolutionary songs and danced. At that time I met Raya Malykhina, a girl from another school. We remained friends for over 75 years. She was an obstetrician, a surgeon, a professor, a Doctor of Sciences and head of a chair in Kiev. My best friend died last spring.

There was a stadium across the street from our house where I skated in the winter. There were many children there. We played basketball and football, and spent a lot of time at this stadium. When I came home I always had the same meal for dinner: boiled potatoes, onions and a big pickle, so, I believe, we were rather short of money. We wore shoes with a wooden sole in the 1920s, but it didn’t even occur to us that they were uncomfortable.

There was a movie theater in the central street in Kharkov. It was called Empire. My brother and I often went to the cinema. He was 17, I was 13 and he never hesitated to take me with him instead of going with his friends or girls.

In the late 1920s all Jewish schools were closed, and my brother Izia had to complete his education in a Russian secondary school. Perhaps Izia took after our father. He had a good ear for music. Our parents bought him a violin, but when he was 4 years old he fell from the roof and broke his hand. Playing the violin was out of the question after this incident, but a career in music remained his dream. Izia played the piano very well. He played pieces from operas and overtures. He liked operas best. He always made my friend Raya and me his audience and by the time we turned 15 we had heard many operas. He was a laborer at a factory, but his dream was to become a conductor. He decided to enter the Conservatory. He played an overture from Carmen at his entrance exam, and his examiners were so impressed that they admitted him after this first exam. He became a student of the Kharkov Conservatory in 1934.

In 1934 I finished my lower secondary education. Raya and I decided to go to a plant trade school to complete our secondary education and learn a profession. We were apprentices at a locomotive repair plant. We had special work clothes. There was a leather jacket with 4 pockets that we were saving for going out.

I became a Komsomol 5 member at the trade school. Besides the profession we chose to learn we studied mathematics, physics, Ukrainian and Russian. After studying in trade school for two years Raya and I went to study at the Rabfak 6. We were involved in some public activities: we became pioneer tutors at a school. The children liked me a lot, and I enjoyed working with them. We spent a lot of time together playing games, skating, and so on. I also made speeches at conferences and was involved with editorial work for the children’s newspapers, Na zminu. It was an interesting job. Our chief editor was Peter Belinskiy, and there were quite a few young Jewish men among the staff, including senior secretary Natan Shafir, my future husband. There were editorial offices of other newspapers in our neighborhood with quite a few Jewish employees. Nationality wasn’t an issue at the time.

In 1933, during the period of the forced famine in Ukraine 7, I was sent to Velikoburlukskiy district of Kharkov region by the Komsomol authorities. I and my companion took a train and then changed to a horse-driven cart. The horse was exhausted and starved. I was very poorly dressed, and it was a very cold day. I was wearing shoes and galoshes. When my feet got frozen I got off the cart and ran after the cart for the remaining part of the road. When we reached Velikiy Burluk we saw dead bodies in the streets. There were many children among them. But it was even more terrible in the houses: crying, dying children and starved adults with distracted eyes. Our task was to make lists of the living and the dead. We did our job and returned to Kharkov after several days.

There were crowds of starving people in the streets in Kharkov as well. The majority of them were villagers. My father worked a lot back then. He worked at the plant during the day and did repair jobs and construction work for people in the evening. He always brought home a piece of bread which he got in exchange for his work. We didn’t starve in those years.

In 1934 the government decided to move the capital from Kharkov to Kiev. Our editorial office moved to Kiev as well and so did I. In 1935 Natan Shafir and I got married. We had a civil ceremony at the registry office and our colleagues gave us with a big bouquet of peonies. Natan Shafir was born to a wealthy Jewish family in the village of Novo-Poltavka near Nikolayev in 1910. His father, Aron Shafir, owned a mill and his mother, Basia Shafir, was a housewife. They had four children: Natan, his sister Sonia, who was 2 years younger than him, Ida, born in 1915, and the youngest child, Aron, born in 1917. They lived in a big brick building with five rooms. They grew many flowers in their garden, had an orchard and a kitchen garden. They also kept a cow and chickens. Natan’s grandparents, Isaac and Leya, lived with them. They were a religious family: they celebrated all religious holidays and followed the kashrut. On Friday Natan’s grandmother lit candles. His grandfather had a Torah. On Saturdays and on holidays the whole family went to the synagogue.

Natan finished cheder and wished to continue his education. He went to Nikolayev where his father’s brother David lived. David was a baker. Natan entered a secondary school in Nikolayev and finished it in 1928. Natan’s cousin, Mikhail, got married and moved to Moscow with his wife. He was a confectioner there. Natan decided to go to Moscow. He entered the Institute of Journalism there and worked as a reporter with the Pioneer Pravda newspaper. Upon graduation he got a job assignment in Kharkov, and that’s how we met.

In May 1936 our son Yuri was born. I hired a babysitter and continued to work. We lived in a small one-bedroom apartment, but later we received a two-bedroom apartment in a big house. Employees of the newspapers Soviet Ukraine, Communist, Youth of Ukraine and the Stalin’s Generation lived in this building. There were quite a few Jewish families living there.

In 1937 Natan and I were fired and expelled from the Komsomol. We were accused that we drove from Kharkov with Gregory Furman (the head of the school department at the Komsomol Central Committee), who had been executed by that time after having been declared an enemy of the people, and that we were hiding the fact of his anti-Soviet activities. Actually it wasn’t Furman who we drove with, but someone called Belinskiy, but we lost our jobs anyway and had nothing to live on.

We sent Yuri to my parents in Kharkov. We were selling clothes to survive. We sold my coat and Natan’s leather jacket and trousers. The horror of the situation was that we were ready to give up our lives for the Soviet power, but were accused and persecuted in return. It was morally hard for us. We believed everything that happened to us was a terrible mistake and didn’t lose faith in the communist ideas. Every morning when we woke up, the janitor of the house, Kolomiets, told us which of our neighbors had been arrested.

In 1938 the Central Committee of the CPSU [Communist Party of the Soviet Union] decided to alleviate charges against people and we took an effort to resume our membership in the Komsomol. I submitted my request to the regional Komsomol committee. There was a commission that was to review my situation. They requested a letter of confirmation signed by Belinskiy to be submitted to them and promised to have my request reviewed at their meeting. But on the day of their meeting I got to know that Belinskiy had been arrested. So my case was left at that. Natan and I resumed or membership in the Komsomol and got our jobs back only at the end of 1938. We took Yuri home.

In 1939 war in Europe began, but we didn’t believe that Hitler would attack the Soviet Union. In May 1941 my husband Natan was mobilized to a tank military unit on the Western border, but still the beginning of the war was a surprise to me. At 4 o’clock in the morning on 22nd June 8 air raids began in Kiev. I was alone at home. Yuri was in the sanatorium in Evpatoria.

Men from our house went to the front, and women and children were getting prepared for evacuation. I had to get together with my son. I called the sanatorium. They told me that the children were to be taken to Kharkov and from there to Russia. My brother Izia went to the station in Kharkov every day, and one day he called me to tell me that he had my son Yuri with him. I went to Kharkov by train but at one station I heard that our train would change direction to Russia. When walking down the railway station I met an acquaintance, the employee of an editorial office, who told me that their train was heading for Kharkov. My mother’s sister, Zoya, and her friend, Galina Davidenko, were with me on the train, and my acquaintance arranged for us to change to his train. The train took us to Osnova station [50 km from Kharkov] and was going in a different direction from there. We got off the train and got to Kharkov on a section car, and I finally reunited with my son, my parents and my brother.

In July 1941 my brother Izia was mobilized. He died at the end of 1941. He fell ill with spotted fever at the front and was sent to hospital where he died. His wife, Katia, and his 4-year-old son, Alik, were in evacuation in Akhtyubinsk where Katia was working at a plant.

Our family in Kharkov consisted of my father and mother, my mother’s sister Manya and my father’s brothers and sisters. I became an employee of the satirical magazine Perets [Pepper]. My husband found me there in September 1941. There were air raids in Kharkov, and Natan mailed us priority evacuation permits. Those allowed us to evacuate to Tashkent, but I decided that the climate there was too hot for Yuri and only wanted to go as far as Orenburg [about 3,500 km from Kiev] where my friend Vera Krivenko and her mother and son were in evacuation.

All members of my family and relatives were in evacuation during the war and nobody perished in the Holocaust. Izia perished at the front, though. My mother, father, Yuri and I got off in Orenburg. We settled down in Chkalov near Orenburg. In the beginning we were staying with Vera who helped me to get employment at the editorial office of the Chkalov Commune newspaper. My father made oil lamps from waste tins and sold them at the market. And again he came home with a piece of bread during our most difficult times.

Later we rented an apartment at the Fornshtadt neighborhood that was quite far from the center of town. I went on business trips all the time, Yuri stayed with my father and mother. I didn’t have any warm clothes so I borrowed my father’s boots and his jacket. During my trips he stayed at home waiting for me to come back and give him his clothes back. It was only in 1942 that I got the opportunity to buy boots; and I got a warm jacket from work. Going by train was very risky. There were lice and the risk of getting typhoid was very high. I rubbed my underwear with special ‘K’ soap that helped against lice and prevented to get typhoid that way – this soap must have disinfected my clothes to some extent.

At the beginning of the war, my husband started working in the editorial office of a tank unit on the Western border. We often received letters from him. Some of them were published in our newspaper. He wrote that he had been awarded a medal on 10th May and this day became especially memorable to him as it was also his son’s birthday. He wrote that with each roar of cannonade he thought, ‘This is to hit Hitler on the head for Kharkov, Kiev, for Yuri and for all mothers’ tears!’ I would like to read a letter that he wrote to Yuri on his birthday. It was a month before he perished.

‘My dearest Yuri, I hope this letter reaches you on your birthday. You will turn 6 on 10th May. Your Daddy wishes he could be with you on this day and give you a present and kiss you on your little up-turned up nose. Here’s what I wish you: to have your grandmother Rosalia make a huge pie with raisins in Kiev on your next birthday, cream and other sweets; that we meet as soon as possible and I find you, Mummy Ida, your grandfather and grandmother healthy and happy; that you always remember Soviet soldiers that are shedding their blood for all boys and girls, fighting for your happiness, your laughter and your home. You are a big boy now, and you understand how difficult things are for your father and your mother. But we shall be together one day. We shall go to work and you will go to school, but we shall get together in the evenings to talk and recall the past. We shall read nice books, travel, go to the cinema and enjoy life. My dearest, you have so many nice things ahead of you. I keep thinking about you and your Mummy, and I’m ready to give everything to you, even my life. Happy Birthday and many kisses. ‘Hurrah!’ to the birthday boy!’

In summer 1942 I stopped getting letters from my husband. I was very concerned. At first I was notified that he was missing. At that time Stalin issued an order to attack Kharkov at a time when the troops weren’t prepared for such an attack. As a result, over 100,000 soldiers were encircled and eliminated in this area. Natan and their whole editorial office perished. Natan was a good soldier (he was awarded a medal ‘For service in battle’) and a skilled professional, a good father and husband. My son lost his father when he was 6.

Everyone celebrated Victory Day on 9th May 1945. I did, too, grieving for my husband, though. We were happy to have my father with us.

During the time in evacuation he told Yuri a lot about Jewish holidays and made him a Chanukkah dreidel on Chanukkah. He also made him a rattle [for Purim]. My son was the one who had these toys, and other children borrowed them from him to play. My father taught Yuri to do many things: fix household appliances, do some carpeting and metalwork. My son became a very handy and hard-working man.

I would also like to tell you about my husband’s sister, Ida Mogilevskaya. She was an eye doctor at the Filatov 9 clinic in Odessa before the war. Ida went to the front on the first days of war and worked as a doctor in hospitals. Her husband had very poor sight and stayed with their little son, Arkadiy. I corresponded with her during the war, and after the war she visited us in Kiev. She held the rank of a captain and had many orders and medals. After the war she lived in Odessa with her husband and son. Ida worked at an ophthalmologic clinic.

I returned to Kiev in spring 1944. It took me two months to get back. It was necessary to have an official paper that served as a residence permit 10. I had a letter request from the Perets magazine that served as a permit to go back to Kiev. Our apartment was occupied by other employees of the magazine and it took me some time to get an apartment in the same building. Yuri sent me letters asking me one and the same question: when was I going to take him back to Kiev. At the beginning of 1945 I received a room (20 square meters) in this same building and my father, mother and Yuri could come from Chkalov to Kiev. After a year I received a nice two-bedroom apartment: Yuri and I stayed in one room and my parents in the other.

I had worked with the Perets magazine for a year when I got a job offer from the children’s magazine Barvinok. Actually, I was supposed to establish this magazine. I had recently become a party member, was very enthusiastic about building a new life and overwhelmed with patriotic feelings. Our editorial office was in Vorovskogo Street. There was one Jewish employee at the editorial office. His name was Abram Reznichenko. He was an artist. He had been in German captivity during the war. He survived because he managed to keep it a secret that he was a Jew. He painted portraits and this often saved his life. He was especially good at making portraits of Stalin and had no lack of work. He had many job offers from children’s publications and from the Communist journal. I worked with the Barvinok magazine for 27 years.

We were very enthusiastic about the formation of Israel in 1948. The communist ideology and Zionism could exist parallel in our thoughts. We felt so happy for our people that gained their own land and managed to turn it into a blooming garden. In the same year the campaign against cosmopolitans 11 began, but none of my acquaintances suffered from it.

After the war I met a journalist called Gregory Limonov. We got married in 1950. He was Russian. My parents wanted me to marry a Jewish man, but they didn’t have any objections against our marriage. We had a small wedding party at home with close friends, my parents and Yuri. In 1952 my second son, Evgeniy, was born. Regretfully, Gregory and I separated eight years later.

The majority of people were crying bitterly after Stalin’s death in 1953. At meetings they spoke about him as if he were God. People didn’t know how they were going to live without him. They had faith in him. Many young artists and students of the Institute of Art went to his funeral in Moscow. In 1956 after the Twentieth Party Congress 12 all communists in our editorial office heard about the denunciation of the cult of Stalin at the closed meeting, but only very few believed it. I believed it because I remembered the terrible events of 1937.

My parents kept Jewish traditions in our family: my mother got matzah at Pesach, although the synagogues were closed, made delicious beetroot soup, gefilte fish – a mixture of chopped fish and seasonings, which is poached and served cold with horseradish, a traditional Ashkenazi food – and baked teyglakh (a sweet meal made from matzah flour). I wish I had asked my mother for her teyglakh recipe. My colleagues always looked forward to having my mother’s teyglakh. My parents fasted on Yom Kippur.

Yuri went to school. He studied very well. He finished school with a gold medal in 1953. It was also taken into consideration that his father had perished at the front. He was admitted to the Polytechnic Institute. Yuri married his fellow student, a pretty blonde girl called Julia, in 1957. She came from Melitopol. She had a Jewish mother and a Ukrainian father. They had a wedding in autumn, and in spring they graduated from the Institute and got a job at the Zaporozhye transformer plant. In 1957 my father died, 11 years later my mother passed away.

Yuri worked at this plant for 44 years. He designed transformers that were in demand at foreign markets, but he didn’t go abroad to advertise his products. He wasn’t allowed to because of his nationality. I felt so unhappy about this. Yuri always identified himself as a Jew and has always been interested in Jewish culture and history.

In 1958 their son Alexei was born, and their daughter Elena followed in 1966. Alexei took an entrance exam for the Polytechnic Institute in Kiev in 1975. He lacked one grade for admission and had to return to Zaporozhye. I do think that his nationality played a role there.

Something similar happened to Yuri. While working at the plant he began to write his thesis. He had to study to complete it – such was the rule – and he decided to enter the Institute of Electrodynamics in Kiev. I had a meeting with the deputy director of the Institute and confidentially asked him whether nationality mattered. He lowered his eyes and replied, ‘Yes, to a certain degree’. Yuri entered a post graduate course in Moscow and defended his thesis successfully. He became a candidate of sciences. Yuri cares so much about his work. He is 67 but he wants to work as long as possible.

Alexei entered the Polytechnic Institute in Zaporozhye and came to Kiev upon graduation, where he met a very nice Jewish girl. Her name was Sveta Semkovich. They got married and lived with her parents. Their daughter, Katia, was born in 1987. But their family fell apart. Alexei returned to Zaporozhye. He has another family now and a 5-year-old son called Volodia. His daughter Katia visits him on holidays and vacations. Katia is 15 years old and in the 10th grade. After finishing school she wants to enter the Kiev Pedagogical Institute.

Yuri’s daughter Elena graduated from the Zaporozhye Polytechnic Institute. She is also a transformer specialist. She lives in Israel with her 14-year-old son, Ilia. She works at a transformer plant. Elena invited me to move to Israel, but I declined. I’m too old to move to another country, and besides I can’t even think of leaving my motherland. Ilia has a good conduct of Hebrew and so does Elena. They are doing very well.

My second son Evgeniy has always identified himself as a Jew. He has a Jewish mother that raised him. When the time came for him to receive his passport, he had no doubts about what nationality he was going to have put in there. After finishing school he went to work as a carpenter at a plant. In 1969 he entered the Faculty of Industrial and Civil Construction at Kiev Construction Engineering Institute and graduated in 1974. In 1978 he married his colleague, Ludmila Bogomolova. She’s Russian. They have two children: Olga, 22 years old, and Andrei, 16 years old. Ludmila respects my Jewish identity. They visit me at Pesach, Chanukkah and Purim. I cook traditional Jewish food.

Evgeniy is head of the Industrial and Civil Construction Department at the Design Institute Dorproject. The institute supplies its developments to Moscow, Leningrad and Kazan. They provide supervision of road, bridge, crossing, and other construction sites in Moscow; and Evgeniy manages quite a few projects. Ludmila is a good engineer. She works at the Road Institute. Olga graduated from the Faculty of History at Kiev University with honors. She married a young Jewish man and gave birth to a boy, Dima, a year ago. Her husband Evgeniy studies at the Kiev-Mohyla Academy. Andrei finished school and entered the Kiev Engineering Construction Institute.

I’m happy to have my children living near me. I don’t want to move to Israel or Germany. My nephew Alik and his mother have lived in Germany for ten years. I am still surprised that Jews want to live in Germany after the Holocaust. Although I do believe that there are many good Germans. I don’t care about America. My cousins from Kharkov moved to the USA in the 1970s, but I stayed. I am very attached to this land.

I’m a pensioner. I believe that I achieved much in my life. I’m happy about it. I’ve lived an interesting life. I had wonderful parents and I’m very proud of my sons. I had an interesting job and met many intelligent and educated people. I worked within the Ukrainian circle of writers, artists and journalists and my nationality wasn’t an issue. I have always been respected. I had many Ukrainian and Russian friends throughout the decades.

In the recent years of my life I have become very close to Jewish culture: I light candles on Sabbath and fast on Yom Kippur. I go to the synagogue on Jewish holidays whenever I can. I often spend time at Hesed. I attend lectures in Jewish history, concerts, and have meals there twice a day. We can have fish there, which we cannot afford to buy. They provide services to us such as visits to the doctor and they even supply us with medication. We can go to a hairdresser, have a dress altered at the dressmaker’s, and have watches repaired. We can go to the library and borrow a book. And it’s all for free.

I only receive 156 hryvna [approx. US$ 30] as a pension, but Yuri and Evgeniy support me. Besides, I don’t need much. Evgeniy and Ludmila often visit me. On the eve of Pesach I get some matzah at the synagogue. We also celebrated my 80th birthday at the synagogue. I went there with my friend Lisa Usherenko, and there was a TV-team who filmed the two of us when we entered the synagogue. There were five other people whose jubilee we celebrated. There was a big party. We made speeches and had gefilte fish, strudels and other traditional food. We received gifts and were very pleased with this party. I’m 88 now but I don’t think I’m old. I find life very interesting and want to see more of my children and grandchildren in the future. I want to see a rich and happy Ukraine. I wish there was peace in Israel.

I don’t feel like deleting a single day or hour from my life. I don’t know how many years I have ahead of me, but I pray to God to give me more time, and have my good memory and energy last to enjoy life with my close ones and to become no burden to them. I thank God for everything.