Galina Levina is a beautiful, medium-height woman. She has a huge mane of wonderful curly black hair.

She lives in a small apartment not far from the Park of Victory. She has been walking here, in this park, for many years with her many dogs.

Nowadays she has two nice and clever miniature schnauzers, the father and his son.

Galina knows a lot about her ancestors; she tells me about them with great pleasure and humor, she is interested in what she is talking about.

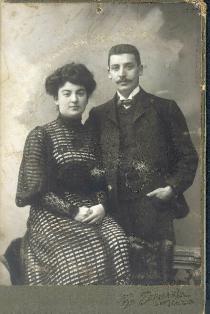

Since the ‘old times’ she keeps numerous high quality photos – after all her maternal grandfather was a merchant and,

as a rather wealthy man, could afford such photos.

My family background

According to my impressions, one of my great-grandfathers was an industrialist. This was the father of my maternal grandfather. I don’t think he was a big industrialist, but my grandfather got some start-up, some money for starting a business, from his father. In my opinion, he was somehow connected with timber industry, and he lived in Ukraine. Grandfather never told me about his mother. I don’t know exactly if they were religious or not, but I think they were, because they raised my grandfather in a religious atmosphere.

My grandfather and grandmother, my mother’s parents, lived in Kiev [today capital of Ukraine]. Granddad had a shipping business on the Dnepr River, he had six or seven ships; one of them was called ‘Mikhail’ in his honor, and another was named ‘Anna’ after my grandmother. 1 The Jewish name of my grandfather was Mendel, his family name was Makhover, and this family name was very well-known in Ukraine and Belarus. He told me, ‘Galenka [short for Galina], I never signed anything.’ This means everyone trusted in his word, and if he gave his word, the problem was solved. Grandfather taught me: you should live in such a way that your word would be enough for everyone. My maternal grandmother was a beauty, naturally, she never worked, and she kept the house and raised her two children: my mother Debora and her brother Mikhail.

Grandfather was a merchant of the First Guild 2, that’s why if he wanted, he could live in [St.] Petersburg or in Moscow 3 before the [Russian] Revolution 4. Of course, he was quite a rich man, he had a couple of houses, and he rented them out, and also his ships gave him a certain income. Granddad loved his ships very much, and also he loved dogs and horses and in Soviet times he was very sad for he couldn’t keep pets and horses any more.

Once someone told my grandfather, ‘While you were at sea, your wife got a lover.’ In Jewish families, especially of this kind – I mean rich and well-known – such things happened very seldom. My grandfather was sad about this fact itself, but also he didn’t like that this lover was ginger and small. I don’t know if they knew each other and were introduced, but my grandfather certainly had seen him somewhere. Grandfather himself was a really handsome man. And soon seven Jews, representatives of Ukraine and Belarus, the most honored community members, divorced my grandparents. Their children, Mikhail and Dora – this was my mother’s home name – stayed to live together with their father. They said they wanted to live together with their beloved father, when one asked them about it. Of course, Granddad had a strong personality, he was the cleverest person, and people came from everywhere to get his ‘wealthy’ advice. And also he had the features of a real merchant; it was hard to break him.

Maternal Granny Anna – in the family they called her Anyuta only – got married, and she lived together with her second husband in Moscow later on. I went to see her, while in the 7th or 8th grade of school, and my mother met her, too, after the Great Patriotic War 5, I think. Granny Anna died in Moscow; she didn’t have any more children.

When the revolutionary events started, Grandfather didn’t emigrate, even though he had an account in one of the Swiss banks. Later he explained his decision to me: ‘It was interesting to watch and see how the entire story with all those down-and-outs would finish. I couldn’t believe that something would come out of it. I thought that since I’d transferred money I would be able to leave in some extreme case.’

Just after the Soviet power was established, he got to know another Jewish woman, Olga, my step-grandmother, my second Granny, and married her. She had two children, too – daughter Teresa and a boy, unfortunately, he died very soon, and I don’t remember his name. Her first husband, Nesnevich – of course, he was Jewish, how could anyone marry a non-Jew then – was a journalist, he couldn’t take the establishment of the Soviet power and threw himself into the Dnepr River. He threw himself from the bridge, obviously, there was some ice on the river, and he killed himself.

When the searches started, and someone came, my maternal grandparents put all expensive things like different diamonds and so on, in a sack and threw this sack from their window into the snow. They thought they’d find this sack later. But someone else found all those treasures and took them away. Finally, Grandfather was arrested, and the shipping on the Dnepr stopped. But, after all, the Dnepr isn’t a regular river somewhere in Zhmerinka [small town in Ukraine not far from Vinnitsa]. The workers said, ‘you should prove to us that our owner is alive, otherwise, none of us will go to work, and you wouldn’t be able to do anything with us.’ And how can you stop the shipping? So they held my grandfather for three days, and all his seven ships were anchored, not moving…

Grandfather told me that when the Bolsheviks 6 let him out, all the ships were anchored in the port and met him with loud hooting. All the staff were in their places. Soon the authorities proposed Granddad to become head of the Leningrad Trade Harbor. And then Granny Olga – I call her Granny because she raised me – said, ‘Mikhail, you shouldn’t have contact with these down-and-outs, I wish you to die in your own bed in your time and day.’ She was a clever woman, wasn’t she? So he agreed, ‘Yes, Olga, you’re right.’ However, it was impossible to stay in Kiev any longer; they were very well known and so on, so they moved to Leningrad [today St. Petersburg]. They moved together with my mother, her brother Mikhail and Granny’s daughter Teresa; her son was dead already.

In Leningrad Grandmother together with Grandfather settled in a big communal apartment 7, which was situated on the corner of Mayakovskaya Street and Baskov Road. Earlier it belonged to one rich Jew, so rich that he was allowed to live in St. Petersburg in Tsarist times. And after the Revolution they divided this apartment into separate rooms. Granddad had some jobs in Leningrad, but, as a matter of fact, he didn’t have any serious job, perhaps, he decided to behave very modestly, not to attract attention to himself. Granny didn’t ever work.

In 1934 – you remember, they moved from Ukraine to our awfully wet climate – Teresa, the daughter of my step-grandmother died from tuberculosis. She was a girl, she was almost of the same age as my mother, and my mother was born in 1907. Anyway, in 1934, just after Teresa died, I was born. And Granny was always happy to hear when people told her, ‘your granddaughter is very much like you.’ This continued till her death. Of course, it was completely impossible, but everyone said that we looked alike. To tell the truth, my grandparents were the ones, who really raised me. They told my parents, ‘Live and enjoy your life, and we will take care of your child.’

Grandfather gave me a lot in this life. He always talked to me just as if I were an adult, and he talked to me a lot. He taught me many truths, which are completely right for me till today. For example, he said that among two people arguing you should blame the cleverer one. I remember, even after the war, Grandparents lived in Ozerki [earlier outskirt of Leningrad, today part of the city], we walked for a long time, and when we came back, Grandmother went out to the courtyard and started to cry, ‘Oh, Mikhail, we worried so much. You left and took the child with you. You are an adult, you are old, and you took the child away.’ She had something in her hands, maybe, a towel and threw it at us. So Grandfather said, ‘Okay, let this woman rest a little, we’d better walk a bit more. She is tired, and we’ll be very quiet.’ His ‘don’t pay attention,’ his understanding… this is what he gave to me. Granny, of course, loved me very much, too; she even had a broche with my picture in it. And also she worried very much, because I was very small. She said, ‘Mikhail, what would happen, what would happen?’

Also I remember walking with Grandpa in a garden not far from ours and he said: ‘My dear, what can I say? Do you see these women? A man would do nothing for these tired women with bags and sacks. Do you know why this State will die? Because they destroy the family.’ So it happened. Or he started to discuss various women, ‘I should tell you that I never liked Parisians.’ – ‘And whom did you like?’ – ‘I liked Warsaw women the best, they are tall and stately. While those Parisians are small and dark…’

It is necessary to outline that my maternal grandparents understood each other very well. My maternal grandparents never argued, never tried to understand what kind of relations they had, because those relations were still very good. They formed a classic Jewish family, they both were ironic people, and they could make fun of each other. They never argued over anything and what should they have argued about? After all, they had such a life, they survived together…

Grandmother Olga didn’t have any brothers or sisters, otherwise I would know about them. And Grandpa had a big family. But he told me only about one of his brothers. This brother was small and a blunderer. This brother, Yankel, had a daughter, whom my Grandpa called Nurka Demishigina [the female form of the Yiddish word meshuge, meaning crazy.] ‘Of course, – my Grandpa said, – could Yankel give birth to another daughter? He himself always was a little bit crazy. His daughter is simply like him.’ Yankel was Grandpa’s younger brother, and I know nothing about all the other ones. Granddad said that he always supported Yankel, because he never had any business of his own.

Certainly, my maternal grandparents knew Jewish traditions. Grandfather had a tallit and a prayer book, he knew the prayers, and he read and wrote Hebrew. At home, at ours in Leningrad, they baked matzah. Adults made the dough, made the holes with a fork, and then we, the children, carried this matzah to the stove. We celebrated Pesach: we drank wine, Grandmother always made kneydlakh out of matzah, I remember that you shouldn’t put any fat in these kneydlakh. She cooked other Jewish meals, too: red beef, teyglakh, kugel, tsimes 8. But I have to say that Grandpa never had any religious faith, especially after World War II. He said he couldn’t understand the God, who killed his children in gas-chambers. ‘I don’t understand Yehova [one of the Hebrew names of God], – he said, – perhaps, I just cannot understand Him.’ I remember well his other words: ‘Darling, there is no God, but He watches everything.’ As for Granny, she wasn’t religious at all, and that could be seen from the fact that her first husband was a liberal.

My maternal grandparents were both buried at the Jewish cemetery. I had a service for them in a synagogue, according to Jewish laws. But now I wouldn’t find their graves, because I lost them somehow: once I didn’t want to go to the cemetery, everybody blamed me then. Grandpa died, at the age of 91, this happened in 1962, which means he was born in 1871. Granny Olga Evseevna died, at the age of 76, also in year 1962; this means she was born in 1886.

I have no idea what my paternal grandparents did. They had some small business, I don’t know what exactly. I know they were from Belarus, later they lived somewhere in Ufa [big town in Ural, capital of Bashkortostan], and there they had some craft, connected with furs. After the [October] Revolution started, they fled to Petrograd [today St. Petersburg], where their elder daughter happened to live. My paternal Grandpa was called Mark Girshevich Markman, and Granny’s name was Chaya. Even though we lived in the same apartment, I spent much more time with my maternal grandparents, and I visited my paternal grandparents from time to time only, so I had much fewer contacts with them. I can’t say we had bad relations, but they had many grandchildren, apart from me.

I don’t know if my paternal grandparents were religious, however we celebrated Jewish holidays all together. I remember Pesach better than all the other holidays, perhaps, because celebrating it, they cooked the best and the most remarkable food. Of course, Grandpa Mark and Granny Chaya knew Yiddish; they usually spoke it to each other. My maternal grandparents did the same. Not to hide something, it was just easier for them to speak Yiddish. Anyway, all my grandparents spoke both – I mean Yiddish and Russian – languages and dressed in an absolutely secular manner.

My maternal grandparents had good neighborly relations with the paternal ones. I can’t say that they kissed each other or showed their feelings somehow. Probably, my paternal grandparents considered that my mother wasn’t good enough for their son, and on the contrary, my maternal ones didn’t think their daughter should have such a husband. Those were eternal Jewish ‘mices’ [discussions in Yiddish]. Then they tried to divide the child. Anyway, they never had conflicts. Apparently, we never had such things, something like conflicts and arguing. All that started after the grandparents died and another generation appeared, everyone began to hate my husband, and of course, he irritated them on purpose.

My parents

My mother was of the same age as my father, they both were born in 1907. Mother spent her childhood and youth in Kiev. Of course, she had babysitters and tutors and servants and so on, everything usual for rich families. She studied at the gymnasium [high school], she took music lessons, she learned to sing and, maybe, she had a chance to finish one or two years of Conservatoire. In Leningrad she didn’t have any possibility to get university education, so she entered secretary courses and worked as a typist.

My grandfather told me that earlier, still in Kiev, he had scared away my mother’s fiancé. He didn’t like his checked trousers, while my mother was almost dying for him. Grandfather didn’t want to forbid his daughter anything, so he organized a party and even fireworks on one of his ships on some occasion. And he asked the sailors to act like they were washing the ship deck and to throw cold soap water over this guy in his checked trousers, all over him. Mother, being 15 only, saw all that and never met him again, of course she stopped dating him, because he looked funny.

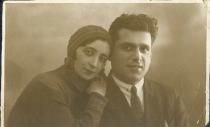

My mother got to know my father just after they came to Leningrad, straight at their home. The point was that in this communal apartment, where my grandparents settled, my paternal grandparents lived, too, they lived there together with their numerous children, including my father. My Dad, Moses Markman, was a very handsome man, huge, very tall, with wonderful, gorgeous hair and big eyes. He even had to order his personal shoes. Then there were very few such tall people, and at a small factory, called ‘Skorokhod’ [today this is one of the biggest shoe factories in the north-west of Russia], they made shoes for those, whose size was bigger than 42. And even though my mother was of a very modest appearance, she wasn’t nice or tall, she was much smaller than him and reached only his shoulder, still he liked her, and they got married. It happened in May 1933. I know nothing about their wedding; my parents never recalled it or talked about it.

My parents were completely different people. Mother was a strict woman, she liked to have order everywhere, especially in the wardrobe, and she liked everything lying in a certain order, while my father was a bit bohemian, it’s enough to mention that ‘Carmen’ was one of his favorite operas. All the time he wanted to go out, but my mother was very strict: she said that she wouldn’t go there and would think if she should go to some other place. So they ended up with quite difficult relations, while my maternal grandparents took me in to let my parents stay alone. I think my parents were unhappy together. Granny told me often, ‘Darling, you should remember this for your entire life. Dora is our daughter, that’s why we must be on her side, but it is the woman, who makes the family, and it’s her fault that they aren’t happy.’

All her life Mother worked as a secretary at the factory, nowadays called ‘Samson’; it’s not far from Kirovsky factory [biggest factory in Leningrad at the time]. Father worked at the factory, too, but he had some engineer’s position. Of course, he graduated from high school, but I don’t know if he got some more education, if he studied somewhere else. They earned good money, and as for money we didn’t have any troubles. We lived like regular cultured people of this time. Certainly, our family wasn’t a professor’s family; my parents were working intellectuals. Our house was a typical house of people, who had to leave their native places and move to another one; here they built something necessary for everyday family life. We had ancient furniture, but I doubt it was the furniture of my grandpa, which he took with him; I think we rented a furnished apartment from the very beginning. Also, we didn’t have a library at home, nevertheless both Mother and Father liked reading. Of course, we had some books, but not too many.

My parents weren’t religious people, not at all. Certainly, they celebrated some Jewish holidays together with their relatives, but they didn’t pray. Mother never cooked Jewish meals, and they wore secular dress only and didn’t speak Yiddish.

In the communal apartment, where I grew up, everyone was my relative, only my aunts and uncles lived there. Grandpa Mikhail together with Granny Olga lived in the former cabinet, the Lobkovsky family, some other relatives, lived in the hall, Granny Chaya together with her husband Mark lived in the dinning-room, and Father’s sister Maria together with her family lived in the former bedroom. We lived in one more room. We always communicated a lot with my father’s relatives. He had a brother, called David – his home name was Dolya – and four sisters: Nina, Irena, Maria and Sophia. All of them, except Sophia, lived in Leningrad, and I had contacts with them till their deaths. Sophia lived in Vitebsk [today Belarus] and later she moved to Moscow.

Apparently, the husband of Nina, the elder sister, was that certain Jew, who was previously the owner of this apartment. Nina never worked, neither did Irena or Sophia, because their husbands were some bosses and earned money. For example, Nina’s husband, Mark, worked in the sailing industry; however in 1937 he was arrested. After he came back from prison, he married for the second time, because Nina had died in the Blockade 9, and went to America with his second wife. Irena’s husband – I think his name was Felix – was an engineer, he worked as a head engineer in some institution, connected with water supplies. And Sophia’s husband was a civil servant. The younger sister, Maria, graduated from the Medical Institute; she was the only one among all children, who got university education. She was married to a Leningrad radio editor-in-chief, who was responsible for the news department. His name was Zinovy Lifshitz. David, just like my father, worked somewhere as an engineer.

Mikhail, my Mom’s brother, got university education, he studied in the evenings or, maybe, at external courses. He worked in ‘Svetlana’ industrial co-operation. Mikhail together with his family lived in Lesnoy [far-away city district]; Mother didn’t communicate with them too much. I can’t say they weren’t friends or something; it just so happened. He had a not very pleasant wife, she was a Russian woman, and her first husband was a policeman. She had two adult sons. Everyone wasn’t too happy with Mikhail’s choice, above all my Grandpa. Later they had a daughter, my cousin Vera. Before World War II my grandparents went to the South for vacations and they brought her a present from there: some eastern national costume. Of course, they loved her; she was their own granddaughter, after all. Later we lost touch with each other, and I don’t know what happened to her further.

Growing up

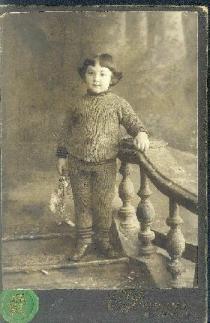

I was born in 1934 and I could never understand why my documents say that I’m ‘Galina Shmuilovna,’ since my father’s name was Moses. They say this was a joke of my uncle David, my Dad’s brother – I don’t know why it was a joke, maybe they meant my mother had some boyfriend, called Samuel, or maybe my uncle didn’t think that I was the real daughter of my father? Anyway, my relatives thought it was funny, but I never considered it funny and hated this name very much! I never had tutors or babysitters. However, I had a German teacher, Bertha Samsonovna, she taught children both German and good manners. She kept a private kindergarten: we were seven or eight children in one group, and every day we went to one of our homes, including our apartment, too.

My maternal grandmother together with my grandfather took care of my health and feeding. Every half a year they showed me to some professor, famous pediatrician, who put his hand on my ass and said, ‘Absolutely healthy girl, but it is necessary to eat porridge.’ And every day in the morning I had the duty to eat a plate of porridge and drink a glass of juice.

When I was a little girl, we went to a dacha 10 in Sestrorezk [small town, famous spa and dacha place not far from Leningrad], but I can’t recall any details. My maternal grandparents went to Kislovodsk [town in the south of Russia, famous for its spas] every year in the pre-war times. They didn’t take me together with them, because scientists considered that a child under the age of five or six shouldn’t change the climate. So they were going to take me with them in 1941. They thought I would start going to the music school the same year.

In my childhood I was a very nice and good-looking girl, my childhood photos even hang in the art photo studio on Nevsky Prospekt. My parents dressed me well, Mother sewed and knitted. Also I had splendid long hair, and just after the war started, they cut it. This happened while I was going to another kindergarten, attached to my Mom’s factory.

During the war

Just after World War II started, my Dad was mobilized to the army. He was in regular troops, served as an ordinary soldier somewhere, not far from Luga [small town, 180 kilometers south of Leningrad], maybe even in Nevskaya Dubrovka [small settlement, 120 kilometers from Leningrad]. There he disappeared without any explanations.

I was evacuated together with my kindergarten. There was such a mess! So the kindergarten went to Pestovo railway station [not far from Leningrad], and German troops arrived there, too. All our tutors ran away, leaving the children. I don’t know what was going on with other children, I heard that somebody gathered them back and put them on some train or echelon, and it was bombed all over. However, outwardly I looked typically Jewish – big dark eyes, dark, almost black hair – and local inhabitants started to hide me in their homes. They took me together with another boy, I don’t know if he was Jewish or not. I remember this entire situation quite dimly, I know that they transferred me from one house to another, and also that I had some plastic dolls and I was playing with them. Then Mother reached this station somehow and took me away together with this boy, before the blockade [of Leningrad] ever started. She went to Pestovo by horses and echelons, and we returned back with numerous stops and transfers. I can say only that I’m very thankful till today to all those people, who hid me, risking their lives, and there were no Jews among them.

Finally we came back, and then, almost at the same time the Leningrad Blockade started. Earlier Mother had some lung troubles already, and now she got an open form of tuberculosis. It was impossible to leave her and we had to stay. I remember very well Granny asking Granddad something about fire-wood, Mother was then lying in bed. Granny said, ‘Mikhail, what about the fire-wood?’ and he replied to her, ‘I went to the cellar, there is no more fire-wood, there are dead people, put in rows.’ Apparently the best food I ever had was so-called ‘duranda,’ or blockade bricks. I still recall its taste. Somebody gave me, perhaps, more than the usual ratio, my relatives supported me. When the blockade was partly lifted in 1942, we were evacuated, we crossed Ladoga [large lake in Leningrad region], and bullets fell very close, just nearby [Road of life 11].

So far we were evacuated to Siberia, to Kemerovo [big town in South-Western Siberia] region. Mom was very weak, almost dying. And here Grandfather used all his sharpness, intelligence and skills. He said, ‘Exchanging our stuff, we couldn’t live too long, while we need to take care of Dora and raise her child.’ Near the village, where we were living, seven kilometers away, there was a forest logging area. It was derelict, and Granddad asked some Communist Party bosses to let him work there, he promised to organize the work, if he got a house, where his family would be able to live. He wanted to sell the wood, and for the money he expected to earn, he wanted to buy hay for the Red Army.

So they offered us a house with a Russian stove 12, and almost at the same time I began to shout. It was a big scandal, and I was demanding a dog. I cried and asked and so on, and my grandparents didn’t want to listen or to see me crying, so they went to the neighbors and found some doggy. I named him Marsik, after the Mars Field [one of the best known places in Leningrad, where they organized military parades before the Revolution], like a real Leningrad child that I was. At first we could take only one cup of milk, and this milk was given to my doggy. So Mother raised him, and he became an adult dog: small, white and with a nice short tail.

So we finally found a place, Grandfather organized the work on this forest logging area, and then the first thing he did, he bought a cow. Of course, my Granny couldn’t milk a cow, but Grandfather said ‘you should’ and she learned how to do that. This cow was called Sedanka. Mother drunk some milk, too, and step by step she felt much better, and she started to work too, she was employed somewhere in raikom [regional committee of the Communist Party], as usual she got a job as typist. In my opinion, this cow gave less milk than an ordinary goat. Then Grandfather went to where they cut the meat, and they agreed to exchange Sedanka for Manka, a cow of some better kind. Someone loaded the herds and directed her to us. This cow Manka gave us fifteen liters per day, I learned to make butter in a bottle, and we got sour cream, cottage cheese. To tell the truth, we started to live much better. I have very nice memories about those times. I remember us somersaulting naked in the haystacks, and how I pastured the cows together with local children. There were a couple of cows in the village, in the morning we went to the pasture, in the daytime we made them go back – for the milking. Local children taught me which grass the cows eat, how to dig out roots, I learned many other cunning things, too.

While we were evacuating to Kemerovo, my mother said, ‘You can take three things only.’ So I took ‘A Captain at Fifteen’ [adventure novel by French writer Jules Verne (1828-1905)], a doll and a bear. Together with this ‘Captain at Fifteen’ book I came to the first grade of a local village school. The teacher asked, ‘Did you read it?’ I answered, ‘Yes, I read it,’ and started going to this village school. If it was warm outside, I walked, and when it was cold, like forty and more degrees below zero, Granddad drove me there on the sledges. My cut hair grew a little by this time, and local children exhibited me, walking from one house to another. I was like a wonder! For they were all blond, they had bad hair. I recall them taking my hair in their hands, looking at it and saying, ‘Wow, what a dark color! What black hair!’ There was nothing like anti-Semitism, on the contrary, they said, ‘Black haired girl, so nice, so neat.’

My paternal grandparents, on the contrary, didn’t go into evacuation. I don’t know why, probably, they were very weak by this time. They died of starvation, and the same happened to Nina, my father’s elder sister. Obviously, Mikhail, my mother’s brother, was an important engineer, that’s why he didn’t have to go to the army. So he stayed in Leningrad, he got some ration, but, perhaps, he gave it to his family. So he died during the blockade, and his wife died, too. We didn’t keep contact with him and his family, because even though he lived in Leningrad, he lived quite far from us and we didn’t have the strength, we were too weak to go there. After all, my mother lay ill and my grandparents had to take care of her and me and they didn’t have time to go there, too. So we didn’t communicate a lot during the Great Patriotic War – we didn’t see him often before it either – and then he died.

Post-war

Anyway the war was finishing, and we had to go back home. However, Grandfather didn’t want to go empty, without anything he earned. So he found an echelon, transferring horses, and made an agreement. They had to take us with them. Our place was separated into two parts: their horses in one part, and our family together with the cow in another one. Grandfather took this cow with him! We went for 21 days together with all those horses, our cow, a supply of hay and my dog Marsik. However he needed to be walked, and after we arrived to Novosibirsk [big town in Siberia], we left him there after we found somebody, who agreed to take him. We left him, but we kept the cow and were dropped off with this cow at Efimovskaya station, it is somewhere in Novgorod region [as a matter of fact, a village called Efimovsky is situated in Leningrad region, not far from Novgorod region, perhaps, long ago the station was really called ‘Efimovskaya’]. There we lived for almost two years, I think.

I started school at the age of eight and I studied in Siberia for two years only. In Efimovskaya they had only one school, and there I studied for two more years. However, studies didn’t attract me too much. One little girl asked me later, ‘Galina, of course, you were the best pupil, you had only excellent grades?’ I replied to her, ‘Dear Catherine, not at all, I never got good grades.’ She was so happy about it, ‘Thank God, you are the first adult I ever met, who wasn’t the best pupil with all excellent grades.’ I remember myself sitting in Efimovskaya and playing with knives, while our teacher walked nearby. Then she told me, ‘You’d better not play, you’d better go and study,’ she said because I’d just got another ‘three points’ [grade, equal to American C].

Once my grandparents discussed my school successes. They spoke Yiddish, using Russian words very seldom, from time to time, and of course they thought I didn’t understand them. But I understood everything very well; although I never spoke Yiddish before. Granny didn’t like that I had ‘three points’ for Math and for Russian, too, and she continued, ‘You pamper her too much, you should stop it, you need to talk to her.’ And Granddad replied, ‘If the child has got a bad grade, this means only that the teacher didn’t try to make his subject interesting.’ My maternal grandparents were sincerely sure that their granddaughter was the cleverest and most beautiful girl in the world. I listened to all that, listened and after some time I couldn’t take it any more, so I interrupted their discussion and they had to understand: ‘she knows Yiddish.’

Later, while in Germany, I understood German as well. Two drivers were talking. They agreed to tell a group they’ll be coming at one time, but as a matter of fact they wanted to come later. So I went to our group and translated this conversation, being proud of myself. Group members asked me, ‘How do you know? How did you understand them?’ and I explained to them, ‘They speak German, and German is a bit like Yiddish.’

So I should return to the postwar times. Finally we sold our cow and moved to Leningrad in 1946. Our room in Leningrad was preserved, because we were the family of a military, killed at the front – at the end of the Great Patriotic War we got a message from the military authorities, where it said that my father had died, but it wasn’t a usual so-called ‘funeral paper,’ it was a regular letter, saying he died somewhere, and the place of his death was unknown. However, my grandparents couldn’t live in their room any more, for someone was registered there, too 13. They had no place to go, and since they didn’t have a room, they had to rent a house in Ozerki. We continued to live in Leningrad, in our communal apartment, and I left for Ozerki on my vacations. In front of their house in Ozerki there was some campus, it is still there, and I always see it going somewhere in that direction. They lived in a wooden house, which doesn’t exist any more, and then the authorities gave them their room back.

In Leningrad I studied at school #193 14, which they wanted to rename and give it the name of Krupskaya, Lenin’s wife 15, but they never did. The school was situated very close to our house, it was almost next door, and I didn’t even put on a coat to run from our entrance to the school hall. After school lessons together with my classmates and friends we ran back to mine, because we had a large, 28 square meter room, and it didn’t take any time to walk. My maternal grandparents encouraged these meetings. I communicated a lot with my schoolmates, I was friends with all our class, and we were quite friendly teenagers. I didn’t have any friends outside of school.

I can’t say that I liked any subjects more than other ones. Nevertheless, I was keener on Physics. Otherwise I wouldn’t have worked as an engineer and constructor for so many years… I don’t remember anything special about my teachers either. Perhaps, only the Russian language teacher, a wonderful woman, she had been arrested and exiled in 1937 16. She was always surprised, ‘You are reading a lot, why do you write with mistakes, why is your spelling no good?’

That’s true, I read a lot. I remember my childhood books very well: Chukovsky [Chukovsky, Korney Ivanovich (1882-1969): Soviet poet and writer, famous for his books for children], Marshak 17, later another favorite book appeared, and that was ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’ [by American novelist Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-1896)], then I liked ‘A Captain at Fifteen’. As a very little girl, way before school, I very much liked ‘Peter the First’ by Tolstoy [Tolstoy, Aleksey Nikolayevich (1883-1945): Soviet writer, author of many famous novels, including the trilogy ‘Road to Calvary’ (1946) about the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the historical novel ‘Peter the First’ (1959)]. Studying at school, I remember very well, I asked Mom about Lev Tolstoy 18 and she said, ‘I don’t advise you to read ‘Anna Karenina’ [novel by Lev Tolstoy] now, because you will understand nothing.’ Mother seldom advised me what to read and what not to read; nevertheless her recommendations were always very clear.

Teachers never loved me the most. My friend Tatiana, whose father was the head Surgery of the Leningrad Military Unit and a general, was the teachers’ favorite. She was some super excellent girl with excellent grades; everyone paid attention to her, liked her and told her parents, ‘She is such a good girl, why is she a friend of this Galina Markman.’ However, Tatiana wasn’t impressed with all those conversations and her parents, I should thank them, too, they didn’t pay any attention to them either. Anyway Tatiana had real a professor’s home with a huge library, with leather furniture and with all those things, which are the real heritage and are passed on from one generation to another. Later Tatiana applied to Leningrad University and entered it, now she is retired, but she still works in Pulkovo observatory.

I can’t say if I felt any anti-Semitism from my teachers’ side, anyway, they didn’t ever demonstrate such sentiments. Perhaps, they were anti-Semites, and it could be seen in their eyes? However I’m such a person, who doesn’t pay attention to some things, I’m able not to hear, if not needed, that is my grandfather’s influence, too. People wouldn’t tell me something unpleasant, because I could talk back, or it wouldn’t make a big impression on me, like on other, more sensitive human beings. Later, as an adult, I heard things like: ‘look, there’s a kike going,’ or ‘your friend is a kike’, or ‘so many kikes everywhere.’ But I never reacted to all this.

As a school girl, I wasn’t just a pioneer 19, I just loved it! Maybe, it’s because I’m a social animal. I liked meeting people and going to pioneers camps a lot. After all, it was something quite different, because I did nothing more on my vacations. And I must mention my school vacations were quite boring: I spent them in Leningrad and did all the same as on the other days. However, I’ve been a bad Komsomol 20 member; I joined it for I knew it was necessary to do so. That was the only reason. Still I never joined the Communist Party.

I didn’t cry when Stalin died. I understood more or less what was going on, perhaps, they discussed politics at home. Maybe, my parents talked about it, maybe my Grandpa. Anyway, I knew what I should talk about outside and what I shouldn’t. Thank God, none of my relatives was arrested or exiled, but all this performance in 1953 after Stalin’s death was real fun for me.

I ran around all the time to find a book, I knew exactly that I had to find Akhmatova 21, or Yesenin 22, and you had to read them ‘under the table,’ otherwise it was dangerous. I’ve heard about Kirov’s 23 plot and what was going on in 1937. I never felt any delight because of Stalin or Lenin, not at all. Probably it happened because they raised me as a sensitive, intellectual girl, without any idols. Also none of my relatives were Communists; none of them joined the [Communist] Party.

Just at the time I finished school, my Grandpa was completely handicapped, and also his cataract worsened. He was a very big man; his weight reached 100 or 110 kilograms. Mother was ill, too, she had tuberculosis. Naturally, I couldn’t even dream of university, I had to work. I needed to earn money as soon as possible, so I entered some Mechanics College of Instruments and Equipment. It was quite a hard time, but, still I ran around somehow, dated boys, went to theaters and museums, I’d be queuing for hours for tickets to the philharmonic. Apparently, as I understand now, it was a very interesting and amazing time. We read poems – Akhmatova, Tsvetaeva 24, I had many friends at college.

Later, in 1954, my mother died. So we stayed, the three of us: a completely sick Grandpa – lying in bed and not walking – Granny, who never worked in her life, and I. So my Granddad was lying in bed for nine years, sick and blind. Everyone told me, and the doctors, too, ‘You have to take him to the home for the handicapped, the house of invalids,’ they promised me to help with it, and they asked me, ‘Why do you want to keep him, you are a little girl, what a horror to have this ill person!’ But I said ‘no.’

I started to work at the steel-rolling factory, in the instrument department, where I worked my entire life. First I was an assistant to the master, and then I became an engineer-technologist, later I got a constructor position. I spent my entire life in the rolling shop; I didn’t want to leave for the research institute, even though they offered it to me hundreds of times. I thought the rolling shop was something alive. I had wonderful relations with everybody, although my colleagues were very simple people, they could curse with rude words and so on. Anyway, they were representatives of the real working class, not like today. After all, the instrumental rolling shop is always the elite. One of the workers told me once: ‘So, I went to the impressionism exhibition and looked at all those Degas dancers. And what? There are fat blue women standing, nothing else. That is no good, it doesn’t make any sense.’ [Degas, Edgar (1834-1917): French painter, associated with the impressionists, who portrayed, among others, ballet dancers, milliners, laundresses and women at their toilette.] So, we discussed this topic. But as a matter of fact they took care of me; they liked to have something extraordinary like me.

I remember only one occasion, but they told me about it many years later. There was a lay-off, and in the dressing room one of the workers said, ‘Why did they discharge Ivanova, and leave Levina? She is Jewish, they’d better dismiss her!’ Then my other mates beat him. And later, many years later, somebody was talking to me and said, ‘Don’t you remember this guy; we even beat him because of you?’ I asked, ‘How come you beat him? Why?’ Then they told me this entire story. When I first came to this factory, there were quite many Jews, but later we were the only ones [because of the campaign against ‘cosmopolitans’ 25]: me, because I was nothing, assistant to the master, and a stove-maker. So we, this stove-maker and I, crossing the courtyard, smiled at each other. They dismissed many people, even the head of the industry, and who cared about me?

The grandson of Grandpa’s brother Yankel, son of his daughter Anna, Lazar Berman became a famous piano player. Anna taught music, and even when Lazar was very little, he was lying in his child’s bed and wasn’t speaking, she decided he had wonderful ears, a good ear for music, and announced him to be a wunderkind. And really, Lazar Berman became the laureate of numerous competitions, he played together with Maria Goldshtein, they even got watches from Zhdanov [(1896-1948), Soviet political and ideological leader] and other gifts. Later he got an apartment in Moscow, and then he built a ‘cooperative apartment’ [in the USSR apartments were not private, the State decided itself where citizens should live] in the same house, where Alexandra Pakhmutova [famous Soviet composer, born in 1929, wife of Nicholas Dobronravov, a poet, they wrote their songs together] and other musicians lived. I went there for some holidays, for New Year for example.

Lazar was surrounded by interesting people; he had good friends and company. He often came to Leningrad, too, he gave concerts here and was courting me, but I couldn’t marry him because I couldn’t leave my grandparents alone. I remember one funny situation: once after his Moscow concert we went to the zoo, and his mother Anna followed us, she kept the distance of three or four cages, but still followed us. She observed us crossing the road, because she was afraid something would happen.

When he understood that we wouldn’t ever be together, he made one very foolish step: he married a French woman, she was called Christine. Of course, the authorities didn’t let him go abroad any more [in the USSR authorities decided which people should go abroad and which not, people, married to foreigners, were included into the group of risk]. We were friends till his emigration from the USSR. Later he sent me a piece of newspaper – then the information about weddings and divorces was published in two newspapers: ‘Evening Moscow’ and ‘Evening Leningrad’ – where it was said that ‘Mister Berman, living at the following address: Moscow, Cheremushki etc, is announcing his divorce from Madame Christine, citizen of France, living at the…’ They got married on Bastille Day, on 14th July, and lived together for half a year only. Later he got married again, now he is married for the third or even for the fourth time. Nowadays he lives abroad, in Italy, I think. We don’t keep in touch any more, the connection was broken somehow. I don’t know exactly if he became really famous abroad, too, perhaps, he is known to great music fans, but I don’t think he is considered a world famous musician.

In 1962 Granny died, and Grandpa was completely blind by then. So I stayed alone with a bed-ridden old man, of more than 90. The same year he died in my arms, too. It was summer, and according to Jewish traditions, I had to burry him in three days and I had to hurry, because the weather turned to be very hot. Somehow I bought 21 meters of fabric, and together with my relative we took my grandfather to the synagogue at the Jewish Preobrazhenskoe cemetery. There they said: ‘For the first time we observe two women, a girl and another one, accompanying a 91-year-old patriarch.’ Also they were very surprised that he’d been lying in bed for nine years, but there were no bedsores on his body. So they washed him, cut his cloth and buried him in the same place where my mother and Granny were buried earlier. Also there was a Kaddish, and everything necessary. Numerous relatives of my father came to the funeral; however none of my mother’s came, because almost all of them were dead by that time.

After my Grandpa’s death I stayed to live in the room, where my grandparents had lived; our room – I mean the room, where I lived together with my mother – was already given to someone else. And once I came home, all my neighbors, who were mostly my relatives, met me and said, ‘Some American woman came to see you.’ I thought, ‘It is the last thing I would dream about! It is the only thing, needed to kill me.’ So they said she left an address, ‘you should call the hotel near Art Cinema.’ I went to this hotel, found this woman and learned the following story from her:

When she was seven or something like that, the Revolution took place, my Grandpa gave money to people, who were going to emigrate. He himself decided to observe what was going on, to wait a little, and to watch how all this would end up, and gave his money to others. So the parents of this girl left with her and later they asked her to find Mikhail Makhover, when she could, and thank him and bow to him. She found me with the help of the information service and came, while I was at work. She was quite an old woman, or she seemed to be old, and the first thing she said was, ‘I want to complain!’ I was surprised, ‘Why do you complain?’ She spoke Russian, obviously, her parents taught her. ‘You are the granddaughter of Mikhail Makhover, – she continued. Shame on you, you rent out your apartment! Some unknown people went out from their rooms and none of them offered me a cup of tea!’ So I had to explain to her that everything was different than she imagined.

This woman lived in Leningrad for about ten days only, but I told her a lot about Soviet reality, we went on excursions to Leningrad and Petrodvoretz [Peterhof, town on the outskirts of Leningrad, before the Revolution it used to be Tsar’s summer residence, was founded by Peter I], visited the cemetery. She was surprised seeing people reading serious literature, non-fiction instead of comics on the underground. Later we had to talk cars:

– Why can’t we drive your car?

– What car?

At first she didn’t understand, but soon she guessed why I didn’t have a car, earning 690 rubles, not a good salary. Most of all I was afraid they would pick me up after she left… 26 However, nothing happened; the authorities didn’t arrest me, didn’t exile or even invite me for a talk. The only thing I had left from her was a lipstick she gave to me. She didn’t give me anything more or write me later, but I don’t complain because I didn’t expect any better, since I didn’t like her too much.

Married life

Once I was at home, not looking particularly good, I was wearing a home dress and didn’t wear any make-up. At the same time my cousin, who was living in our apartment, too, had a birthday party. I, due to some reason, didn’t want to participate in it and said I wouldn’t go, I don’t remember exactly what happened. Anyway I was sitting alone and acted like I was very angry. My cousin invited a young man, who was dating her at the time, and he took his friends with him. So they had more guests than they could host, and they were looking for an additional table. My cousin said, ‘We can take Galina’s table, but she is angry, who is going to ask?’ So this boy, a friend answered, ‘I don’t care. I never knew her and won’t know, let me go, which room is it?’ Soon he called and asked something about the table. I said, ‘This is the table. Here you go!’ He left, but then he came back and said he was bored with them. This guy turned out to be my future husband.

My husband, David Levin – I always called him simply David – was really a handsome man and a very easy-going person. Then you couldn’t marry quickly, we had to wait for two months, but he arranged it. He said he was going to have the so-called Komsomol wedding, that’s why we had to pronounce slogans for the Soviet power and so on. I was already 30, and he was five years younger, he was born in 1939.

David’s ancestors came from Staraya Russa [town in Novgorod province, 300 kilometers south of St. Petersburg], there were plenty of sanatoriums in this region, and his father Samuel played the accordion there. David’s mother, Asya Davidovna, finished the music college, she had a good ear for music, and she was an accompanier for various sport competitions, she played for gymnasts and other sportsmen. When David was a little boy, she took him to those competitions and he grew up a sporty boy. His mother earned good money; she was an absolutely bohemian woman, who never paid attention to her home duties or her family. She didn’t like her husband, I can say she hated him; she didn’t need him at all. She wasn’t keen on her son either, I would say, she never paid attention to him, and until the age of 14 it was his Granny, her mother, who took real care of David. This grandmother was an ordinary Jewish woman, she never worked, she was a housewife. After she died, they buried her at the Jewish cemetery.

David’s father was killed during the Great Patriotic War somewhere not far from Staraya Russa, I know he was very young; he was only 25 or 26. David’s family moved from Staraya Russa to Leningrad, here he finished college. He inherited some talents from his parents: he had a good ear for music and dancing skills.

Seeing me for the first time in her entire life, his mother, looking in her sons’ eyes, said the following: ‘You always dated such beautiful women. What did you find in this one?’ David asked me not to pay attention to her. During our Komsomol wedding, which looked like a real madhouse, she said to my aunt: ‘You have such a nice girl. What did she find in my foolish boy?’ My aunt ran to me with eyes wide open and asked: ‘If his own mother says he is a fool, maybe you shouldn’t marry him…’ I answered her just the same: ‘Don’t pay attention.’

When we got married, David was keen on classical jazz. At this time I was completely indifferent to this jazz: I was raised in museums and philharmonic halls. There was a famous conductor, Mucin, and his son was courting me, he accompanied me to classical music concerts. Anyway, David invited me to a jazz concert. Oh, my goodness, we went to the jazz club ‘The square’ [famous Leningrad jazz club] for the first time. And the concert was a long one, because all jazz concerts last for quite a while. I don’t know why I didn’t leave. However, I went there for one more time, when he invited me once more, but this next time I wore a different dress, not that one I put on for classical music concerts. Later we often went to these jazz concerts, I got used to his hobbies and he tried to participate in my usual activities. I put on some bright make-up, put on some necklaces and so on, and all of David’s friends marveled in amazement: ‘Wow, what a beautiful woman, what a wife, she accompanies him, while ours don’t want to.’

We lived very well, of course, we argued sometimes, but as a matter of fact we ‘complemented each other.’ We looked absolutely different, we had different characters and hobbies, but we were alike in our feelings and in our thoughts. That’s why I wish everyone to live as good a life as we had together. We had only one trouble. I couldn’t ever have children. Those were the consequences of the blockade; nevertheless nobody gave me any diagnosis or explanation. We didn’t want to adopt children, I don’t even know why. Just didn’t want to take somebody else’s child.

I had one more special feature: I had milk teeth, as an adult. I found it out when I went to the dentist polyclinic not far from Maltzevsky market, and some very nice woman, a dentist, said I have milk teeth. She directed me to the x-rays, and they found out that I really had four teeth without the roots, and since it wasn’t nice and those teeth were very weak, they pulled them out. So I got artificial teeth and wore them for the rest of my life. In the dentist polyclinic on Nevsky Prospekt, near ‘The North’ [famous patisserie; café and a shop] they had statistics, but even they didn’t have such cases in their database. Of course, all that happened because of the blockade. So you can consider me the only person, whose teeth didn’t change as it usually happens.

Just after we got married, I said to David, ‘I’m a woman with a simple college diploma, that is no good, but still I get some respect at the factory. While a man with just a college education is nothing; that’s no good at all. So would you please, my dear, apply for university.’ So he entered the Engineering Energy Institute, he graduated from it after some years of external studies, and his specialization was called ‘specialist in energy.’ While he studied, his friends and mates often came to us to study and he invited them in such a way, ‘Let’s go to mine. I will introduce you to Galina.’ After all I was a constructor, so I drew well and helped them a lot. We had many friends, later some emigrated, other ones died… His friends Eugene Ivanov, Anatoly Afanasiev and Isaya Shnaider – he is Jewish and lives in America nowadays – came over frequently. They were friends even after the graduation. I adored Eugene, he was a very clever person, and the only trouble was that he liked to drink. We always kept a very hospital home, and our life was bright and active.

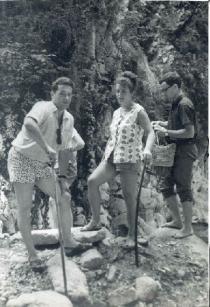

During the first years of our common life David worked at the small plywood factory as the head specialist in energy, and they built the youth camp called ‘Sputnik’ in the South of the USSR, in Vishnevka, near Tuapse [famous Russian spa resort on the Black Sea]. We rented an apartment in the neighborhood, and we ate in the camp, and also we took part in various activities, provided mainly for foreigners. This was a fine time! The sea, splendid conditions, plenty of excursions, and we could wear shorts! When we went to town, everyone pointed at us with their finger, while inside the camp it was considered absolutely normal. While David was studying, we went to this ‘Sputnik’ all the time, climbed the mountains, talked to foreigners, and David participated in ‘Ogonyoks’ [evenings of amateur activities, jokes and performances], danced rock-n-roll. There were quite many foreigners, from everywhere, even from Cuba, nobody forbid us to talk to them, to communicate with people we wanted to communicate with. Of course, there were plenty of informants, but we didn’t suffer from them.

I wanted to have a dog very much. But you have to feed a dog according to a strict schedule, almost every other hour, while we both were working hard. So when David was writing his diploma, I gave him a fox terrier, thoroughbred, with a pedigree. Of course, I warned my husband about this gift, and he said, ‘I was expecting a tape-recorder,’ but then he agreed. And till his graduation he went to all pre-diploma seminars with the doggy in his arms.

This fox terrier played an important and very positive role in our common life. We had two former servants’ rooms in our apartment. One was very small, something like a store room and the other was a bit larger, and there some woman, not a relative, settled. She didn’t like dogs, not at all; she dreamed of getting rid of this fox terrier and offered me some exchange. Of course, our dog wasn’t the real matter; she simply wanted to unite with her mother, who lived in a one-room apartment on Kuznetsovskaya Street. This apartment wasn’t big, the room itself was almost tiny, 13 square meters only, but I loved this idea, it was a chance to get out of the communal apartment... My husband, of course, a snob and hussar, was capricious, ‘I won’t go to the Moscow gates area. I got used to living here; here I have the Nevsky Prospekt nearby.’ And I replied to him: ‘Very well. You won’t go. And I will!’ Of course, we both left and lived in our new apartment. I started to sign the papers, to make an exchange, to collect our stuff and he left, what else could he do?

The last drop, which killed our neighbor from this communal apartment, was the story about the partisans, which took place the last year we lived there, in our communal apartment in the center of Leningrad. As usual I came home from work – I woke up at five o’clock every morning – and stood in the kitchen. In our apartment no one worked, but they all adored teaching me how to live. So this time the same started: I don’t boil the potatoes right, I do something wrong, and so on. Life was much easier for my husband, who was sitting in our room. So I stood listening to all that and suddenly my husband crept out on all fours, and our fox terrier ran, following him. I asked, ‘What’s the matter?’ and he answered, ‘Please, be quiet. We are playing partisans. Do you understand?’ I said, ‘As for me, I understand, but as for our neighbors…’ Then this neighbor, not a relative, said, ‘I can’t take it any more.’ So if we hadn’t had a dog, we would have stayed in this communal apartment for ages. We said good-by to our old house in such a way: we threw an old buffet from the upper floor and watched it flying and breaking into small parts. We got great pleasure from the whole process.

Although we left the huge room and exchanged it for the tiny apartment, I just ‘blossomed.’ I went to the kitchen, and there was nobody else in it, what a pleasure! But the pleasure wasn’t too long: two years later David’s mother broke her leg, and we had to take her to us. So later we had to exchange apartments once more: we exchanged her room and our apartment for another apartment, a bit larger. Then I told David that I didn’t have any time to make this exchange, because I was working and taking care of his sick mother, who was lying in bed, not moving. ‘Try to find something, I said, but I have one demand only, please look for an apartment in this city district only, because we can’t walk our dog in the center, and here we have an opportunity to walk in the park or on the waste plots of land.’ Some time later David said, ‘Do you want to exchange for an apartment in the same house?’ I answered him, ‘With great pleasure.’ So since those times I’ve been living here.

My husband changed many jobs after he left this plywood factory; he worked in his field everywhere, continuing to be a specialist in energy. His last job was at the tram park. David was a very non-conformist person, and it bothered him a lot. When we got him a travel passport, we found out that we can’t put all his jobs on one sheet of paper and we had to write on the additional sheet while I had only one line there, saying I was an engineer at the steel-rolling factory. I still have this travel passport, because he never had a chance to use it. We never left the dogs to anyone, and when we decided to get travel passports and go abroad separately, he was already very ill. I asked him to go abroad, while he wanted to go to the sea, to play volleyball because he was a very sporty man. I could sit near the bonfire, and he didn’t like it, he wasn’t such a person, he liked doing other things.

As for me, I went abroad a few times. However, I’ve not been a Communist Party member, that’s why they examined and made fun of me in raikom. This was such a horror! And every time they said ‘no.’ I didn’t react: ‘no, then no, I don’t really need it.’ Then they called me up to our factory party committee and said, ‘You are going.’ How could they not let me go? I was working in the rolling shop, all the staff knew I was a good employee, I was enough of an erudite and intellectual person. After all, I wasn’t head of department; I didn’t have a car or something like that. So if they wouldn’t let me, I wouldn’t be silent, I would tell about it, and the conversations would start, so people around would think: why didn’t they let her go? Finally they would decide that the authorities didn’t let me because I was Jewish.

So all the time the same story repeated itself: at first fools from raikom and all those dames with awful haircuts and those back combings argued, then they called me up to our factory local party committee and let me out. However, to tell the truth, when I wished to go to Finland, they wanted to dismiss the woman, who brought my documents and papers. They told her, ‘What do you think you are doing? This is a capitalist country!’ Anyway, I had a chance to visit Yugoslavia, the German Democratic Republic, Bulgaria and Czechoslovakia.

Every year my husband and I separated and spent our vacations on our own. It was so: I’d come back, and then David left me the dog and went to the seaside and so on. Somebody always had to stay with the dog. I went on my tourist trips, I liked it very much. I’ve been to plenty of places: to Central Asia, to the Caucasus, to the Baltic Republics, to Solovki [Islands in the North of the USSR, where authorities banished people in Stalin times], to the Golden Ring [picturesque old towns in Russia]. At our factory you could get the vouchers quite simply, that’s why my friend Silva and I, we traveled a lot. Of course, the conditions were not very good, they were even bad, but still we traveled a lot, because it was very interesting. David went mainly to the Black Sea or to the Baltic. In winter we both, David and I, went skiing, we even rented a winter house on the outskirts of Leningrad.

It’s weird but I never wished to emigrate, I don’t even know why exactly. David’s pals came to visit and said he was living with a crazy woman: ‘Definitely, she is crazy. People are doing everything to become Jewish, while you are real Jews, pure Jews, perhaps, from Moses. What else do you need? Why do you stay with this crazy woman and her beloved dogs?’ Besides, then I had only one dog and I could take it with me easily, without any troubles. I worked in a very hard industry, in metallurgy, in dirt, I woke up at five o’clock, I never had any ‘greenhouse’ conditions, but I didn’t want to leave. David said he wanted to go and I told him, ‘Well, if you want to. No one has the right to insist, a person is a person, so if you want to, you should go… I’ll pack all your stuff. You can go alone. Maybe later I will come to join you. But now I’m not going to.’

Perhaps, I didn’t want to live abroad because I wouldn’t earn anything there, because somebody would need to give me things. I don’t know, maybe I made it all up; maybe those are the features of my grandfather, who never wanted to go either, maybe, I don’t have any explanations at all. The most remarkable thing is that I never thought I wasn’t right; I still think the same and never had any regrets about this decision.

When our friends and pals left, I reacted quite normally, I didn’t fall down of tender emotions: ‘Oh, ah, they left.’ Of course, our pals immigrated to Israel, to Germany, to America, and I can’t recall any place where they didn’t go. What could I change: if they left, this means they left? Thank God, today we have an opportunity to meet again. People are calling, people are coming.

I was studying all the time. I finished sewing courses, knitting courses, but my main hobbies always were the dogs. I was involved in the dog business very seriously; I finished the courses, organized exhibitions, participated in them, too. All that took a lot of time, money and strength. Twice per week I went to the club. My husband liked my dog activities, too, he ran around on my dog businesses, too. Our fox terrier lived for thirteen years, we went to an exhibition twice, but they needed a field diploma there [fox terrier is a hunting dog], he had to catch a fox and so on, but he demonstrated his hunting skills only if he found chocolate, not a fox… Since we didn’t get any diplomas we stopped exhibiting him. After he died, after a long pause we went on vacations together. Being on holidays we understood that we needed a dog, we couldn’t live without a dog, so we took a miniature schnauzer, which someone offered to us. Schnauzers were rare dogs; in the USSR it was the second generation only. I didn’t know what this dog looked like. When they showed me a schnauzer for the first time, I recalled that I’d seen such dogs in Czechoslovakia. So we took Duck.

I’m a calm person, but I’m able to get upset and so on. If one told me something bad about my dogs, then I’d lose control and may say awful things. As for David, he was a very impulsive person, as well as his cousin Mark. David didn’t have brothers, but he was big friends with one of his two cousins. Mark was very tall, a meter and ninety seven, and also he was a sport master in fencing. Once I went together with David, Mark, his Russian wife Olga and their little son Vladimir to their dacha to Komarovo [famous elite dacha village near Leningrad]. Vladimir studied in the first grade then, and in the morning he proudly announced to us that it was a day of birds and we had to go to the dacha to hang the bird-houses. So it was done. We made one bird-house and all together went to the dacha to hang it up. In the train we were moving to the exit: I was the first one, holding Vladimir’s hand and this bird-house, then David with his obviously Jewish appearance, then Olga, a tall, beautiful woman, a real Kustodiev [Russian artist famous for his pictures of merchants’ wives] lady, and suddenly some man addressed her, ‘Look around! What fat kikes walked by!’ Mark was following Olga; she turned to him and said, ‘Look, kikes walked by and this citizen doesn’t like it.’ Mark without any word took this man and put him onto the platform. We were standing there with David and Vladimir, his nephew. David asked calmly, ‘What’s going on?’ Mark replied, ‘This person doesn’t like kikes.’ So David beat him, and Mark added some, one of them was a real sportsman; the other played all possible sport games, so this man had enough for one time…

David told me this story many times: ‘I’m going in the bus and see a man making fun of an old Jew. He asks why this Jew isn’t in Israel. So I tell him, ‘Why don’t you ask me the same, you’d better ask me, not him.’ And then this man replies, I have no reason to talk to you.’ ‘Of course, it doesn’t make sense to talk to me, I’m tall and strong.’ So my husband usually said, ‘If you don’t wish to, I will talk to you.’ Finally he beat such anti-Semites and left them.

It’s hard to say if there were many Jews among our numerous friends. Two of my close friends are Jewish, they both live abroad. Another friend, who stayed to live here, is half-Jewish, her mother was Jewish and her father was Russian. My very close friend, unfortunately, she died, was absolutely Russian. My dogs’ ‘friends’ are Russians, too. Nelly Bronislavna, with whom I am quite close, is Russian and Catholic. I never paid attention to nationality, my friends were chosen due to other features. They were people who read ‘The Foreign Literature’ [fiction, essays etc. by foreign writers], we gave this magazine to each other, because it was hard to find it. Working at the factory, I still had friends there. They were people of a completely different circle.

Working at the factory, I never suffered from any anti-Semitic incidents, because I never reached high positions. Maybe, if I had entered an institute, I would have felt more anti-Semitism. I retired upon turning 55; of course, I was very tired and couldn’t continue working. According to our Soviet laws, it was necessary to work two months more, and I remember, some bucket stood near my work place. All that took place in May. So my friends and colleagues came and brought some flowers. They brought these flowers from their dachas: ‘What’s going on? Do you really plan to leave? Please, Galina, stay here. We don’t want you to go.’ Anyway, if I’d had problems or troubles because of my nationality, I wouldn’t have worked there for more than 30 years, what do you think?

I had other troubles working at the factory. Just like all others, we lived in the atmosphere of lies and fears. During all my years at this factory, I never had a lunch, because during lunch break we were hunting for food and products. One of us went to the milk department, and another one went to the grocery. Later we divided everything we bought, we separated it equally. Once we bought a huge set of sausages, and Ludmila Alferova, a blond fat woman with a nice smile, said, ‘If we count those sausages, we’ll never go home, we’ll stay here and count till the end of the world.’ And I said, ‘No, we won’t count, we will put it together, and then put it together once more and so we’ll divide them.’ So we stood in our working room, dividing those sausages, and suddenly the head of the rolling shop approached and cried: ‘you are going completely crazy, what an impossible imprudence. What are you doing here with all those sausages?’ That’s how we were living.

Also I never went to demonstrations, I never wanted to go there, I never agreed to. And every time they reproached me: ‘Why haven’t you been to the demonstration?’ I answered, ‘I don’t have time for it.’ They were very surprised, ‘You don’t have children. Why don’t you have time?’ I continued the same: ‘Anyway I don’t want to go.’ So they made a conclusion: ‘So we are refusing to pay the thirteenth salary’ [so-called ‘thirteenth salary’ was paid at the end of the year for good work]. What could I do? So I didn’t get it. And those who agreed to go to the demonstration got some extra pay: 50 rubles for carrying the banner and 100 rubles for carrying the flag. One of our colleagues lived on Nevsky Prospekt, she told me, ‘So I go to the balcony and see people carrying the flags. And I begin to count: this is one hundred rubles; this is fifty rubles and so on.’ David, my husband, never participated in the Communist activities either; he never went to demonstrations and so on. Fortunately, we both never joined the Soviet Communist Party and never liked Soviet authorities either.

I don’t understand those, who recall these demonstrations with nostalgia: ‘it was so nice, we sang songs, and there were holidays and dances.’ I mean I’m a social person, I liked different activities, but to go, when one makes you go, when you know what’s underneath... I knew exactly and know today that I hate the Communist regime and everything connected to it, I hate all that so much! I don’t understand people of my age; people of my generation, who saw all those horrors, all that hypocrisy, lies, dissimulation and pharisaism, but they still continue to go to demonstrations.

While working at the factory and taking trips all over the country I’ve been to Solovki – which is a nice and interesting place; that’s why both nowadays and in Soviet times people go there for short and long trips, they stay there to see wonderful nature and historical sights, too – in the concentration camp 27, so-called SLON [short for so-called ‘concentration camp of special purpose’], where our best people died in the 1930s during the Great Terror, and when people died, other prisoners hid their bodies in snow to get their ration. I stayed there for four days and saw everything preserved there. There is no need to tell me, who worked at the factory her entire life and knows exactly how they made up all those plans etc, what they signed and so on, to tell me how much the sausage cost [i.e. how wonderfully cheap things were]. Old workers told me, what was going on: ‘We are coming for work and aren’t seeing five more people, seven more people. And we couldn’t even ask where they went, why they disappeared.’ Here I’m talking about the 1930s, about the times of the Great Terror, but it also happened just after the Great Patriotic War; of course, it took place more seldom, but still it was horrible.

When our dog Duck turned 13, I realized that I needed ‘new blood,’ because I had nobody to ‘marry’ my doggy children and grandchildren. I ordered a dog in Finland, and finally I bought some dog from Lapland. All my friends were thinking I behaved crazy buying an unknown dog from an unknown owner. That’s how my Mika appeared in this apartment, my first Schnauzer with tail and ears [in Russia they usually cut them off].

Soon, on 11th August 1994, my husband died from lung cancer. We argued a lot because of his health, ‘David, please, you need to put on the scarf, because you have troubles with your throat.’ And he said, ‘No, I’m not going to, I don’t want to.’ Besides all that he smoked a lot, and this played a role, too. David is buried at the Jewish cemetery; of course, I visit his grave quite often.

In a month, on 16th September, Duck died. I exhibited Mika for the first time, we took part in some junior competition, and he won the ‘best in show’ category. This was a shock! What was going on! I almost cried, while I was walking the lap of honor and cried, because it was such a pity that David couldn’t see us. I couldn’t find the right way. Mika performed very well: in the world championship he won the third position among 362 dogs participating. I consider it wonderful; it was a great result for my dog. So finally I remained living with Mika. And if sometime before I hadn’t learnt cutting the dogs [Galina means that some breeds of dogs have to have their ears and tails cut, and she does it and charges for it], I wouldn’t have a chance to survive. Now I cut the dogs, and for my family, which includes me and my dog, that’s enough. Not long ago I took a little dog, because if something happened to the elder dog Mika, I would stay alone while I’m used to dogs.

My present-day life

As a matter of fact I’m alone now. My father’s sisters all died, his brother David also died about 15 years ago, and his daughter Anna, my cousin, moved to Moscow, because she got married to some Moscow guy. She has a daughter, my niece, who comes here twice a year. She is 26 and, obviously, we are great friends. Anna’s brother, the son of Uncle David, lives in Leningrad, we call each other from time to time, quite seldom.

I’m still in touch with the son of Aunt Maria, my father’s sister, Felix. He is younger than me, he was born in 1936. At the beginning of the war, Maria worked in Nevskaya Dubrovka, and the bomb fell just onto the house where they lived. And she, together with her husband Zinovy, was trapped under this destroyed building. Everyone stayed alive, but Maria had problems with her eye, she was injured. Zinovy was injured, too, and Felix became handicapped: there was something wrong with his leg and something wrong with his head, too. He is a very nice person, but he has teenage brains. However, he happened to have a good ear for music, he finished the music school and later graduated from the Conservatoire. By this time both his parents died. Aunt Maria died of some heart attack, when Felix was studying in the seventh or eighth grade. So Aunt Irena took care of him, then I followed her and started to take care of him, too. Of course, he isn’t married.

Two years ago Felix called me, terrified, ‘Someone rang the doorbell, I opened the door, and they beat me and took all the money.’ He lived then in a one-room apartment on Pulkovo Road, and I asked him not to open the door to anyone. In a couple of days he called me again, ‘Galina, I opened the door, they came again. They beat me; they left a knife and took the TV-set.’ I picked him up, all his teeth were broken, his face like a mask and I said, ‘Felix, you worked in the field of fine arts, so you should go to the House of Stage Veterans on Krestovsky island and ask for a room.’ He argued, ‘I won’t go now, looking like this. I insisted, ‘No, you will go now, with all those injuries.’

So I had to sell his apartment, now he lives in much better conditions, of course, it is a bit sad over there, I go there with pleasure and leave with pleasure, too. However, he is a fine fellow. He feels beauty very deeply, almost every day he goes to the philharmonic hall, or watches ballet on TV: he compares the ‘Swan Lake’ productions with Makarova, Ulanova or Plisezkaya dancing [world-famous Russian ballet dancers]. I had some money left after selling his apartment, that’s why I bought him all new things: a new TV-set, new furniture, and new clothes. He calls me everyday, telling me what happened to him. I don’t have any more relatives alive.

But people I don’t know want to talk to me quite often. Some time ago I met a woman who said that she just loves the portrait of Stalin in which he holds a girl. She argued with me because she didn’t want to agree that this girl was arrested and put in prison upon his order. Finally I had to tell her that she had lived in those times and seen that everyone around her was exiled, that’s why she’d better go tell her stories to those, who don’t know the truth, to those, who didn’t see all these horrors. Really, I can’t understand who is voting for the Communists today, I can’t understand how it is possible?

Another story, connected with my Jewish roots and appearance, is the following one. Once I met a small old Jew, who tried to tell me that I’m Elina Bystrizkaya [a famous Soviet actress, acted in numerous movies, a Jew]. He wouldn’t let me go until I told him that I was her secretary, signing the autographs instead of her, and getting ten percent for such a hard job. So I learned I look like a great actress and have a possibility to earn big money!