Poznan

Poland

Interviewers: Agata Patalas, Joanna Fikus

Date of interview: April-May 2005

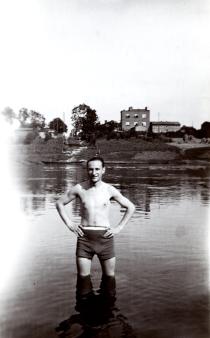

Mr. Leopold Sokolowski is 82 and retired. He lives in Poznan. He graduated from the Political Science Department at the Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznan, but he never worked in this profession. He was a technician-mechanic at the Rolling Bearing Factory in Poznan. His name used to be Pynchas Federgrün, but he changed it after the war. He spent his childhood in Cracow. He was raised in a traditional, not very well-to-do Jewish family. He just managed to celebrate his bar mitzvah before the war. He studied in cheder, went to talmud torah. In his reminiscences, he often uses Yiddish words. He lived through the war in Niepolomice and the camps. He lost his entire big family. After the war, he married a Polish woman from a family with communist sympathies. He is active in Jewish organizations. He is one of the few in the Poznan community who can pray in Hebrew and therefore he is often asked to lead the prayer. Unfortunately Mr. Sokolowski's declining health keeps him at home more and more.

My family history

Growing up

Religious life

During the War

After the War

Glossary

My mother's family name was Schnitzer. My grandmother used to be called ‘the old Schnitzer woman,' and I have to confess I can't remember her first name; I called her simply ‘Grandma.' I spoke Yiddish with my grandparents, so Grandmother was ‘bube' [Yiddish for grandmother] and Grandfather was ‘zeide' [Yiddish for grandfather] and that was it. My grandfather's name was Ksil; I don't know what that was in Polish. Ksil Schnitzer.

They were both trade people. Their trade consisted of my grandfather going to the fair with one of the peasants. He would go to Kroscienko [a town in the south of Poland, around 80 km south-east of Cracow], or to Szaflary [a town, around 70 km south of Cracow], or Nowy Targ [a city, around 70 km south-east of Cracow]. He was a bearded Jew whom people trusted. He used to bring, for example, five geese, five hens and ten dozen eggs. With the help of a neighbor or a wagon driver he would distribute those among the local Jews, those who could afford it.

My grandfather brought poultry from the countryside. When someone bought a hen, my grandmother took it to the kosher butcher, to the ‘siojchet' [Yiddish for shochet], and delivered poultry to the clients which was ready for cooking, that is, plucked and gutted. Clients bought from her, because they trusted her. They knew that poultry from the old Schnitzer woman had been ritually killed by a kosher butcher and if the hen swallowed something at the courtyard, like a nail or something, and my grandmother found it while gutting, she wouldn't sell the hen because it wouldn't be kosher. My grandmother paid the kosher butcher for his work and calculated that and her own work into the cost.

My grandfather on my father's side was Salomon. I have a document that says: ‘In response to your letter, the city of Cracovia archives inform, that the 1921 records list in the city of Cracow: Salomon Federgrün, a shoemaker, residing at Podbrzezie Street, born 31st August, 1872 in Tarnow, permanent residence in Cracow since 1881. His wife, Reisa Federgrün, born 15th March 1872 in Sechna, Limanowa district [a town in the south of Poland, around 50 km south-east of Cracow].' My grandmother died in 1936 or 1937, I can't remember exactly. She was a nanny. I have been to their apartment at Podbrzezie, opposite the Hebrew secondary school, later named ‘Doctor Hilfstein School' [Hebrew Elementary School and Jewish Co-ed Secondary School; since 1936, Chaim Hilfstein's Private Co-ed Secondary School, at the corner of Podbrzezie and Brzozowa Streets; it was the best known Jewish school in pre-war Cracow, which educated children in the spirit of Zionism and Polish patriotism].

My grandfather stopped working before the war; he had Parkinson's and was already shaking. He went blind after one of his eye surgeries and I used to go for walks with him as a 13 or 14-year-old, holding him by the hand. I was very impressed when my grandfather would say, ‘now we will turn left, into Brzozowa Street.' And he was right, he knew. I was impressed he remembered the names of the streets. My grandfathers, both on my mother's and my father's side, were bearded Jews, but they didn't wear a streimel, only a black hat. My grandfather always wore black. He wore a regular coat, not a ‘bekiesza' [a traditional frock coat].

My mother's name was Tonia or Taube, nee Schnitzer. She was born on 14th April 1895, most likely in Nowy Targ. She finished two grades of elementary school. She was a big woman. My father was thinner. My mother was an unhappy woman, because her hearing was bad, probably because of the scarlet fever she contracted when she was a child. That influenced her contact with the world. She stayed at home more. Because of that, she didn't have a circle of friends. She got occasional jobs at richer families. She did the laundry and fixed the clothes she washed. It took two days to do the laundry of a large family. She ate there, and sometime, in addition to the pay, she brought home some food-some bread or cake. I remember she used to do the laundry for a baker's family. In addition to that she used to sew trousers for a seller who went to trade fairs, for example to Nowy Targ. The garments were already cut out and she only sewed them together. Those were cheap work clothes. My mother made some extra money this way.

She had a sister, Sala, and two brothers, Chaim [Henryk] and Pinek [Pynchas]. My mother's sister, Sala, must have been born in 1897 or 1898. In 1923, before I was born, she went to France with her husband. Her husband's name was Max Barasz. He was a Jew from Oswiecim [a town in southern Poland, around 70 km west of Cracow], who served in the Austrian army 1. He went to France, made some money there, and came back to Poland to get married. It so happened that he met my aunt in Nowy Targ and came to get married to her. That was the custom, to marry among one's own. Tonka didn't have me yet, but she was already married to my father.

So Max married the younger sister, Sala. He remained in Poland for a while, working to earn for the return trip to France, and then they went. They must have had a pretty good life over there. They opened a hairdressing place in Paris. Before the war, they visited us twice, I think. During the war, they lived in Paris. I don't know the details, but they say it was very hard. Their children's names were Lulu and Ronny. We used to call them Lulek, I don't know how that sounds in French, and Ronny, Renee, which sounds like the Polish Renata. I think her name was really Ruhl, like the grandmother my sister also got her name after. I don't know exactly when they were born.

Chaim or Henryk Schnitzer was also younger than my mother. I don't know which year he was born, perhaps in 1900. I was born in 1924 and he got married soon after. Before the war, Uncle Chaim lived in Zakopane [a well known tourist town in the Polish Tatry mountains, around 100 km south of Cracow] and in Nowy Targ, until 1939. He died with his wife and daughter, I think [during the Holocaust]; the daughter was younger than my sister, so she must have been born around 1932.

My mother's youngest sibling was her brother who had the same name I do, Pynchas. We used to call him ‘Uncle Pinek.' Aunt Sala encouraged him to come to Paris in 1933 or 1934; they taught him the hairdressing trade and he stayed with them. He visited once. He got married in Paris to Aunt Klara, whose maiden name I can't remember.

My father, Albert Federgrün, Abel, was born on 1st September 1896. He had three brothers and a sister: there were five of them altogether. Uncle Adolf was really Awawie, Uncle Snil was Samuel, the youngest uncle, Dolek, was David, the one sister was Regina and her husband Moniek was Mojzesz Griner.

My father's younger brother, Adolf, made shoes, but he was also a tradesman. Again, that was small-scale trade. He went from store to store and asked, ‘What do you need?' and the shoemaker would say, ‘two boxes of hobnails, clouts, leather for the soles.' My uncle Adolf was really a go-between. He would buy 20 boxes of nails at a discount and then he lived on what he made reselling those. His wife Rega, Regina I guess, did a little sewing. Of course she didn't have a regular workshop, only did alterations on the side. They had a daughter and a son. The daughter, Jecia, was six months younger than I am, born in November 1924. Then there was Leos, slightly younger than my sister, he could have been around five before the war broke out. [Editor's note: Leos was born in 1930.]

Another brother of my father's, Samuel, also did some shoemaking and his wife, Hela, didn't work. Samuel didn't have any children. Then there was Regina. She also didn't work. Her husband, Uncle Moniek, worked as a journeyman at the butcher's. They had two small children. I am embarrassed to admit that I don't remember their names.

They youngest, Uncle Dolek, Dawid, went furthest in terms of professional hierarchies. He became a tailor. Apparently he was a pretty good tailor of women's clothes, and he got a job at the Leon Barciejowski firm, in Cracow, at Florianska 28. A big store, right in the center of Cracow. He was a cutter. That was aristocracy among the professions, for they had very good clients there. He was married to aunt Gusta. He managed to have a child before the war.

My father was the oldest. He was 18 when World War I broke out [in 1914]. He was a newly graduated journeyman, in the profession which used to be called ‘water-main technician' and which today is called simply ‘plumber.' But he didn't work in his profession, only performed various other jobs. For four years he served in the Austrian army. After World War I, he returned to Poland.

I was born on 14th June 1924, into a relatively poor Jewish family, in Nowy Targ. My name was Pynchas Federgrün. We lived in a rented apartment which consisted of one room. I was the oldest and the only son. My sister was six years younger; her name was Ruchel, Renia, Rachela. In writing, the name was Renia. My sister went to a school for girls on the corner of Dietl and Swietego Sebastiana Streets. She managed to finish two grades. She was nine when the war broke out. I remember her as a girl when I was already grown up. I can't remember her games or her toys. A struggle to survive was all that mattered when Father was without a job. Our house is still standing today at Miodowa Street. There was no place where children could play over there. One had to go to the park.

My father first worked in a factory producing paper bags. Factory is a big word: there were three of them working there. One trimmed the paper on a guillotine, another applied glue and the third one put the bag together. Those were popular at the time: triangular, rectangular. My father had an accident there. I may have been four or five; I remember that Father had a bandaged finger. Later he couldn't move that finger. And then I don't know what happened, for one does not consult such things with one's children, whether he was fired or what, but one way or another he got a different job at the Wholesale Flour company.

The owner was Mr. Syrop, whose son, a medical doctor, was a dentist in Cracow. Mr. Syrop had a large flour storehouse. He didn't need many employees. My father would receive a freight-car of flour, enter it in the books and go get a neighbor saying flour needs to be brought from the station. He would hire someone with a horse and wagon to bring the flour from the station. My father only had to count the sacks and enter into the register how many sacks there were of wheat and how many of rye. He was a warehouseman of flour. When a buyer came with a list, say, 200 kilograms, my father would issue 200 kilograms. Then Syrop got sick and closed down his business. He was a rich man. He owned a whole house at the town square. He took up one floor and rented out the ground floor to storekeepers.

In 1935 my father was unemployed. In the small town of Nowy Targ it was hard to find a job. Since my father was from Cracow and had family there, he decided to go to Cracow. We didn't have an apartment there, so we moved in with my father's sister, Regina. Two families lived in a room with a kitchen, at 20 Berka Joselewicza Street. A year or two later [1936-37], my father rented a room from Tajtelbaum; I think it was at 28 Florianska Street. Tajtelbaum had a hat store at the front of the building, at 13 Miodowa Street. He lived in one of the front apartments, on the second floor. I don't know how big his place was, but I'm sure it wasn't poor. Various paupers lived in the two annexes and we rented a room there, on the first floor.

There were about five rooms, each with a separate entrance from a long corridor. In the corridor, about 25-30 meters from our room, there was a water pipe from which we took water and had to carry it to our room in a pail. One had to take walks to the toilet over there, too. We had a brick stove which served for cooking. Two pails: one on a chair, the other under the chair. The enamel-coated pail on the chair held drinking water and the zinc one under the chair I used as a child to pee, because I didn't want to go to the toilet; it was not a water closet type of toilet but one into which things fell by gravitation.

When still in Nowy Targ and before I went to elementary school, I started attending cheder. I must have been four or five. We began by memorizing the alphabet, then we started putting syllables together. I remember that for disciplinary purposes students were taken onto the lap and spanked. I can't remember having been spanked, but I'm sure I must have gotten my hands slapped more than once. The melamed held one's hand and hit it with a reed. And we studied. I studied ‘chymys' [Yiddish for Chametz - Pentateuch, Torah], every year ‘apyats s natchala' [Russian for all over again]. We also did one or two chapters of Rashi 2. The teacher - if one may call that a Rabbi - was a bearded Jew, who spoke in Yiddish and we translated into Hebrew. It took a long time.

I went to cheder until I was thirteen, at least until my bar mitzvah. Right before my bar mitzvah I managed to learn some Rashi. I knew how to read some of those small letters without punctuation. There was a hierarchy: first one studied chymys, then Rashi, and then ‘mysnajec' [Hebrew: Mishnah - part of the Talmud] which was like aristocracy in terms of intelligence. I went to cheder in Nowy Targ, there was one by the temple, but I can't remember the names of any of the rabbis.

In Nowy Targ I went to elementary school. At the time those were separate for girls and for boys. It was called Public Elementary School. I finished five grades there. I went to the sixth grade in Cracow, after we moved there, at Miodowa, 36 Miodowa, I think. The building is still there, but I don't think it houses a school any more. That was J.I. Kraszewski Public Elementary School #8. It was a school for Jews only, because only Jews lived in Kazimierz 3, but it was a regular school, the teachers were both Jewish and non-Jewish and the program was a regular elementary school program. We had religion. I can't remember much from those religion classes at school.

I remember that in Nowy Targ the first five grades were mixed: there were some Jews, but most of the students were non-Jewish. We recited ‘Boze cos Polske' [a Polish patriotic song, religious in character]; they said that, after all, we also believe in God. Obviously when they [the catholic children] had the catechism, we left. I can't remember the name of the teacher who gave religion classes to Jewish students. I have no grade transcripts, they are all gone.

In Cracow I went in the afternoons to Ester Kupa's or Ester Warszauer's Talmud Torah. It was at the corner of Ester Street and Nowy Square [between the two World Wars in Cracow there was a talmud torah at the corner of Ester and Warszauer Streets. It was the oldest Jewish school, in operation since the 17th century, for the children of the poorest. Besides the basic Judaism studies, it taught the Latin alphabet and basic math]. Today there is a medical clinic there - I went to look at it, to reminisce.

I don't think we went to school every day, only some days of the week, two or three. There were a dozen or so of us, the Rabbi would come, we would read and he would correct us, supplement, explain, one would repeat, then we all repeated as a chorus. That was the system. I have to say that several times I went to the Azyjczyk Temple [Ajzyk Temple, known as Ajzyk Shul, at Kupa Street in Kazimierz] out of curiosity; there was a shtibl there, and one could go to additional lectures there. I was interested in that. Before the war, I had no doubts when it came to my beliefs. God and all of that were the authoritative truth to me, unequivocal.

After a year of unemployment [1936], my father got a job at the Syjonistyczny Klub Towarzyski [Zionist Social Club], at 71 Grodzka Street, right at the feet of Wawel. The building is not longer there today, it has been torn down. My father was in charge of the cloakroom, my mother did the cleaning, and I didn't have a function. I was 13 then, just graduated from elementary school. There was a well-known Jewish philanthropist, Miki Aleksandrowicz [most likely it's a reference to an old, wealthy, Jewish, Aleksandrowicz family; in the 1920s and 1930s they owned a large paper company], who lived on Swieta Gertruda Street, and who went to Israel [then Palestine] on 2nd September 1939, I think. My father asked him to finance my school. Aleksandrowicz said, ‘alright, I'll pay for his school.'

I wanted to be trained as a locksmith, but I was not physically very fit, so nobody wanted to hire me. I could try at the tailor's or at the shoemaker's, but not at the locksmith's. So I went to the Jewish Trade Middle School, at 10 Stradom Street. [The Jewish Coeducational Trade Middle School, later renamed Jewish Trade Gymnasium, was created in 1933. Apart from general and professional subjects, subjects related to Judaism were also on the curriculum. It was located at Stradomska 10 Street.] The name of the school's founder was Stendig, I can't remember his title. It was a three-year trade school, which gave accountant or, as they said before the war, bookkeeper qualifications, but no matriculation or qualification for further study. I paid reduced tuition, because I was poor: 15 zlotys a month. Aleksandrowicz put down 150 zlotys and a whole year was paid for. After a year, he didn't pay anymore, and I was already 14, so I went to work.

I became a courier for an institution called the Jewish Economic Council. It was run by Dr. Sternberg, a tall man, whose first name I can't remember. The Council was located at 5 Swietego Sebastiana Street; shortly before the war, it moved to Zyblikiewicza. It was an institution created to deal with the Jewish problems. What were the Jewish problems? The rich had their legal counselors to manage their affairs and the poor went to the Council. It ran a job agency, with which only Jews could register.

Right at that time, two to three months after I started work, Zbaszyn 4 came up; Hitler got rid of several thousand Jews, some of whom were sent around Poland, and some of whom ended up in Cracow. Most of those people belonged to the Jewish intelligentsia, whom the language barrier did not allow to undertake proper work. The Jewish Economic Council held workshops at Koletek Street. They taught manufacturing leather goods: wallets, billfolds, pocketbooks; later they did saddles, harnesses. They gave driving lessons, so these people could find jobs in a short time. I was very poorly paid over there. I carried messages. Say, some Jew reported he needed five workers: they had to be found at their addresses and I delivered those messages. My other job was cleaning; my mother used to come help me and I did the dusting. It went on like that until 1939.

On account of my father's job in the cloakroom of the social club, I knew some of the Jewish intelligentsia, because I used to help my father collect membership dues. I knew that at 2 pm I can find Doctor Zimmerman at Starego 24 Street, but if I come later, they will say he is not available or that he is sleeping. I even had a plan how to get there - that's how I knew where the Jewish intelligentsia lived. One Ohrenstein, director of the Suchard chocolate factory, used to come to the Club with his wife. The wife always brought me three, four chocolates. They lived on Kossaka Square 3. I remember that when I went there to collect the membership fee, I would ring the bell, it would sound - there were no intercoms these days, after all it was over half a century ago -, and I would walk it; a little window would open: ‘whom do you wish to see?,' this youngster would ask me. ‘Director Ohrenstein,' I'd say. Very well. But I would not be let in on the main stairs - covered with a red coconut rug - only through the yard and the kitchen door, where I would hand the slip to the servant who would come back in a minute to give me 2 zlotys or 9.

The chairman of the Club was Izaak Stern, a proxy in a bank located on Stradom Street, in the same building as the cinema. Mr. Bachner was the secretary, Mr. Schwarts was the treasurer; both worked for the same bank. The Club was frequented by the Jewish elite, Jewish intelligentsia, the so-called general Zionists 5, for they were neither ‘mizerachiani' [Mizrachi] 6, nor ‘szomeracajer' [Hashomer Hatzair]7, neither left, nor right.

At the Club, besides the reading room, there was a little café in which one could order tea, coffee and a pastry. Special events were organized, such as the ‘Cabaret Night.' Henryk Vogler, who died several months ago in Cracow and who graduated from Law School before the war, used to work for the cabarets writing scripts. There was also Artur Norman, also an MA, though I don't know what his profession was, another young man, who wrote not only comic routines but also plays. Dances and lectures by various celebrities were also held at the Club. They were not international celebrities, but locally they were well-known.

People came, left their coats at the cloakroom and that was an opportunity for me to make some money. There was a custom in Cracow, I'm not sure if it is a custom today, that when the gates to the buildings were closed at 10pm and one came later and had to ring for the janitor to open, one left a tip. The Club was on the second floor of a building where the gates were closed at 10pm, so when someone left later, I lit the way downstairs with a flashlight, opened the door and got 5 or 10 groszy.

I was socially active. After my bar mitzvah, for two years I was a member of the Akiba organization 8, led by Dolek Liebeskind 9; later Szymek Dranger joined it, then Gusta Dawidson [Dawidson-Drangerowa], both of whom died in Cracow [during the occupation, those three people were the founders of a military organization in the Cracow ghetto, He-Chaluc ha-Lochem]. My kvuc leader - kvuca was the smallest cell [Hebrew: Kvuca - group] - was Idek Tenenbaum. We went on excursions, wore those ties, those shirts, similar to those worn by the boy-scouts, and we learned Jewish and Hebrew songs.

I remember that in 1936, Uncle Pinek came to visit us with his wife and they slept at our place. In the single room, in two family beds, there was Uncle Pinek, Aunt Klara, my parents plus two little cots in which the children slept. That was their last time with us, though nobody suspected it's the last time, of course.

My father's generation - my father and his brothers - were all shaven Jews, who met at my grandfather's on Friday evenings and Saturday mornings, all together, including me, the oldest grandson, and went to pray at 6 Brzozowa Street, to the ‘besmedrisz' [Yiddish: bes medresh, Hebrew:, bejt ha-midrash - the house of learning] across from the Hebrew secondary school. Twice a year, at Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, we went to Remu [a synagogue in Cracow, founded in 1533. In the cemetery next to it, Rabbi Mosze Iserles (REMU) is buried, after whom the temple is named]. One needed to pay for one's, numbered, place. I don't know how expensive that was; everybody went there to pray.

As far as the Jewish traditions are concerned, everything was standard: a Jewish kosher house with everything that needs to be there. Maybe occasionally, at the times of unemployment and poverty, we did not observe the kashrut, but otherwise, there was ‘mychlik,' that is, dairy foods [Yiddish: milkhik - milk products], ‘fleiszik' [Yiddish: Fleishik - meat products] and ‘parowe' [Yiddish: parve], neither meat nor milk, for example herring. There was a separate case for ‘Pajsach' [Pesach]. Some of the cutlery was koshered; one boiled water in the yard. If the aluminum pot was not chipped the whole pot could be koshered there. I know that was observed. My father was not a religious man. He shaved and wore European clothes. But he was a believer and went to the temple every holiday and every Saturday. He and his brothers were very close.

I had my bar mitzvah when I was 13, in 1937. We were rather poor and bar mitzvah is an expensive affair. So I had it not on a Saturday but on a regular working day in the Tempel. [Editor's note: A progressive synagogue in Cracow at the corner of Miodowa and Podbrzezie Streets. It was built in the 1860s. In the interwar period, assimilated Jewish intelligentsia gathered there. Services were held in German and Polish. The best known rabbi of that synagogue was Ozjasz Thon]. Before the war, the Tempel was the most beautiful place. The main shammash in the Tempel was my father's cousin, whose name I can't remember. They wore those hats and robes, I don't know what to call them, and everything was exquisite. There was Doctor Ozjasz Thon 10 and doctor Szmelke, the rabbi. It was a progressive synagogue. The women were separate from the men. Next to the main building there was a smaller shtibl. That's where my bar mitzvah was held on a Wednesday.

Of course, there had to be a minyan; there were always 15 to 20 people, not more than that came. My father bought a bottle or so of vodka. That was a custom in the Temple, on special occasions, but since Jews easily got tipsy, tiny glasses sufficed. The guests were treated to some shortcake and that was it for my bar mitzvah. Poor. I knew that others got a bicycle for their bar mitzvah, or a watch, or something else. Of course I had to study, put on a tefillin. I didn't feel like it; not out of atheism, but because of sheer laziness. Since my father didn't put on the tefillin during the week, he had no moral right to reproach me that I don't pray! It meant getting up half an hour earlier and going to school at eight; one had to do the tefillin and the whole ‘shaches' [Yiddish: Szachres - morning prayer] took almost half an hour. On Saturdays I did pray, I had no religious doubt. Religious doubt came during the war.

On Friday evening my father recited the Kiddush standing up - there was my father, my mother, my sister and I. The candles were lit and there was a glass for ‘Borej pri hagufen' [a fragment of the blessing over wine in Ashkenazi pronunciation; in Hebrew: Creator of the fruit of the vine]. For there to be wine, I used to buy 5 decagrams of raisins on Tuesday; we poured water over them and they sat like that till Friday. Raisin juice was acceptable in place of wine and since wine was too expensive, we had raisin water instead. My mother made fish Jewish style, not carp, only roach, or whatever the small fish were called.

We celebrated a festive Pesach at my grandfather's [Grandfather Federgrün's]. Everybody was decently dressed - my brothers and sisters and my grandfather's family; there were a dozen or so at the table. I asked the four questions. My grandfather impressed me, for he was blind and remembered the answers by heart. I don't know how long the Seder lasted, but everything went according to the rules: there was charoset and ‘knajdloch myt joloch' [Yiddish: knajdlach mit jooch - broth with matzah balls], made from matzah flour; the cooking was done according to the religious rules.

During other holidays, everybody - my brothers, sister, brother-in-law - went to the synagogue. My aunts didn't regularly go to the temple, but the men all did. I carried my grandfather's tallit, because during Sabbath, a Jew was not even allowed to carry a tallit. Chasidim even tied their handkerchiefs not to carry a weight in their pockets, and that was allowed [a handkerchief tied to the trousers was considered part of the clothing and no longer a weight a religious Jew was not allowed to carry during the holiday].

This is the tradition I was raised in, and so I'm emotionally attached to Jewish holidays which remind me of my home; maybe it is so because I lost my family early, I don't know. Often, when I say ‘Barukh ata adonai' [‘Blessed Thou Almighty,' the beginning of prayer], I repeat all that, for it gives me inner satisfaction.

We didn't build a sukkah [for the Sukkot holiday]; it was built at the courtyard at Podbrzezie, where my grandfather lived. We went to my grandfather's with my mother and ate the meals there. I used to string paper decorations, and my father's brothers had sets of boards, a hammer and an axe. There were eight to ten such booths at the courtyard and that was how we celebrated. For ‘sykes' [Sukkot] we had a ‘lilef' [lulav], a palm leaf one waved in prayer, and there was one esrog; on Rosh Hashanah, on Kol Nidre and before Yom Kippur we went to the temple.

On Yom Kippur we went to the temple and when we came back home there was no dinner. After my bar mitzvah I was expected to fast, and I did fast some. My father didn't get anything to eat, but my mother pitied me and sometimes she would give me a roll or a piece of bread. I fasted until noon and then, obviously, a 14-year-old boy needs to eat, even if they tell him not to, so my transgressions were overlooked. I am sure my parents lasted till the evening. During Swijec [Shavuot], one simply went to the synagogue, and said the prayers. I think my grandfather fasted at Tisha be-Av. I prayed, but not before each meal, each bite.

My father wore European clothes: a jacket, a hat. At home we spoke Polish, my father, mother and I. That was good, because I didn't get the sing-song accent. But at my grandfather's we spoke Yiddish. My parents knew Polish, because my father finished seven grades of elementary school and a three-year vocational school. My grandparents also knew Polish.

I can't remember any newspapers. We had newspapers at the Club. They were kept in a wooden frame, mostly Jewish newspapers in Polish, such as Nasz Przeglad 11, from Cracow. There was a weekly from Lwow, Nasza Opinia 12. Sometimes my father would mark a passage in an article and I would read it to Grandpa. My parents spoke with my grandparents in Yiddish, but also in Polish. For a child, I knew Yiddish quite well. We spoke Yiddish at family gatherings. We knew some Hebrew words from prayer books.

At home we didn't discuss politics. Neither my parents, nor my grandparents were involved in politics before the war. We didn't have a tin for Keren Kayemet at home 13. There was too little money to spend it on this cause. We never talked about leaving Poland. Only I was active, as a 13 to 15-year-old boy, in Akiba. I know 10-15 Hebrew songs, and even one in Polish: ‘Although you have a soft bed at home, and you're protected by your mother's caring hand, give your heart and your hands and to Erec, go with the sound of the waves, for Jordan calls you, move on, don't turn back, for your strength is needed by the homeland.' But that was the only political activity, if one may call it political; otherwise nobody was a member of Bund 14 or anything else.

In Nowy Targ my friends were mostly Jewish, but I did have one Polish friend, Sikora, son of a chimney-sweep. We both lived at Dluga Street. In Nowy Targ I didn't experience any anti-Semitic sentiments 15. Maybe I was too young; I was eleven when we left [in 1935]. In Cracow I encountered that more often. I knew that one should avoid Planty between Szewska and Wislana Streets, because those guys with Chrobry swords [emblems of the fascist Falanga organization] 16, could give a Jew a beating. Even though we didn't wear armbands, everyone had his Jewishness written out on his face, somehow. They looked and they knew right away that the nose is too long. We were apprehensive.

I remember some festivities - I don't remember what kind - where students from high-schools gathered at the Town Square. I was a trade school student then, in the first grade. Suddenly a rumor went through the crowd that they are beating up the Jews. So we ran. That impressed me - that we had to run. There were some anti-Semitic signs on the walls. Not what they are today, painted on the buildings, for there was no graffiti back then, but they used to put up leaflets and posters.

There used to be a deputy, though I don't remember whether he was a member of the Parliament or the Senate, his name was Prystor 17 and he wore a little beard. He was one of the anti-Semites. Before the war there was a dispute over ritual slaughter 18. That became a pretext for an attack on the Jews. I knew that anti-Semitism was a problem, but I didn't feel it particularly acutely, because in Kazimierz everyone was a Jew. Only one person in our building was not Jewish, an older woman who was the janitor. My father worked in the Jewish community, so he did not encounter the problem either. Then there was Zbaszyn. Working as a courier I did come across that. They used to say about Zbaszyn that Hitler kicked out several thousands of Jews; chased them across the border, not all of them fully dressed.

When the war broke out 19 I was 15; I had turned 15 in June. One should fear every war, but we knew who this war was against and when the Germans invaded Cracow on 6th September, we were very alarmed. Some of the Jews began to flee to the so-called Zurawica [a town in south-eastern Poland, around 10 km north of Przemysl], where you can cross the San river, but we planned to escape to the Soviet Union. Then my father decided against it; at first he even considered that option, but I was against it. I wanted us to stay together; I thought that a family should stick together.

So we stayed in Cracow, at 13 Miodowa Street, for a period of less than a year. I was an apprentice at a Jewish ironworker's, Guttman's, workshop at 36 Dietla Street. How much of this trade could I learn in a few months? The first ‘voluntary repatriation of Jews from Cracow' 20 happened in 1940, I think. The occupation authorities announced that all Jews had to leave Cracow, but certain groups were allowed to apply for the permission to stay: those who used to serve in the Austrian or German army, those who received German honors, and those who worked in the military industry. These were the criteria. My father did become a corporal in World War I, an ‘Obergefreiter' in the Austrian army [a rank used only in the army's heavy artillery branch before 1919], but he didn't get any orders or honors, he was not a hero of World War I, he fought on the Italian front 21.

One was allowed to choose a place where one wanted to go, as long as it was within the borders of the General Governorship, of course. One was allowed to take all of one's possessions. We took some of our stuff and loaded it onto a horse-drawn carriage. We didn't have too much furniture, for we only had the one room, more or less furnished. My father decided that we'd go to Niepolomice [a town 24 km east of Cracow]. We went there, rented a room, set up house. For the first few weeks we looked for jobs, lived from day to day. The local community took care of us. There was a kitchen which gave out free meals. It was hard, but we managed.

After the eviction from Cracow to Niepolomice, we were speculating about what was going on in Cracow. The deadline for departure was 15th June, I think. But June passed by, then July [1940] and the Germans didn't force the Jews out of Cracow. So my father came up with the stupid idea - though who could have known it then - that we're going back to Cracow. Again we piled all of our so-called furniture, those few sad pieces, onto that one-horse carriage and went back to Cracow. But it was no longer possible to register in Cracow as a Jew. So we set up house in Pradnik Czerwony, one of the districts on the outskirts of Cracow.

My father found a man who rented us one of his rooms. We lived there for less that 24 hours. We set up all of our furniture and the rest of the junk and in the evening, when we were having dinner, a navy-blue policeman 22 came in with the owner of the apartment. Did the owner bring him there knowingly? The policeman asks for registration papers - we don't have any. Then the policeman leaves and the owner says, ‘I'll come back tomorrow morning. If you're here I'm taking you to the police, if you're gone, it's your problem.' That was quite a magnanimous gesture. We didn't even wait, it was 8 o'clock. We managed to live in this apartment for one whole day.

My father's brother also lived in Czerwony Pradnik, so we went to that brother, stayed the night and the next morning we went back to Niepolomice - my father, my mother, my sister and I - on foot, for we could no longer afford a cart. We left all of our things behind, in that room. We disappeared in the evening without saying a word to the owner. Everything was left behind. Those were shoddy things, but still they were our household goods: sheets, a pot, a pan, a pillowcase, a blanket-case, towels. In Niepolomice, we rented an even smaller room, or actually a half a room. One-fifth of it was taken up by the stove, not a tile stove, of course, but a clay stove, with bundles of straw thrown over it. We were left without anything. When it was cold we slept under our coats. No wonder that in these conditions we immediately had lice.

Winter 1940/1941 was rich in snow, so the occupation authorities required that every Jew still in Cracow - already with an armband 23, of course - should work 12 days a month shuffling snow or cleaning sidewalks. One got an ‘Ausweiss' [German: a document confirming identity and employment], which was stamped at work. One needed 12 stamps every month. I took a risk. I took off the armband and walked on foot the twenty-something kilometers from Niepolomice to Cracow, to Mr. and Mrs. Tenenbaum, at 2 Powisle Street, where they lived on the first floor. The Akiba had its rooms on the second floor, and that's how I knew Idek Tenenbaum. Idek was not their oldest son, but the second or third. He was my group leader. I don't know how we got together, but he said, ‘Take a train,' or rather walk - for the Jews were not allowed on trains - ‘over to our house.' I went to their house with an armband - I took it off only for the trip. For we, the Jews, were not allowed to move from place to place.

And I went to shuffle snow for both the Tenenbaum father and son. When one came to work, one handed in one's card and got a shovel in return. Pre-war employees of the city cleaners worked there. The were not Jewish. They were given ten Jews each and told them to clean the street. When the day's work was over, they said, ‘Hand back the shovel and take your Ausweiss.' The card was already stamped.

I stayed with the Tenenbaums for about a month, working all day each day. They were well-to-do; they fed me and gave me a place to stay. After a month I realized what's happening to me, so I thanked them politely and left. Why? I found a louse in my hair. The Tenenbaums were a clean, well taken care of family. Lice were not a novelty to me, unfortunately I came in contact with them before, but I couldn't allow myself to infest the Tenenbaum household. So I left, under some pretext, though I really hated to leave. I went back to Niepolomice. That was my only expedition to Cracow. I brought some money back home which the Tenenbaums gave me.

Later in Niepolomice I worked digging drainage ditches during the summer season. It was a semi-compulsory job. Some of the Jews didn't work. I'm not sure if they paid for it or what. One way or another, I did work, and was given some very lousy payment for that. It was a physical job, digging ditches. In the winter, when the weather didn't allow for digging in the ground, I worked at a sawmill in Klaj. Klaj is several kilometers from Niepolomice, on the Cracow-Bochnia-Tarnow-Lwow route. I had to get on a train going to Klaj, and walk 3 kilometers through the woods at night. I was terrified. Having finished at the sawmill, I went back home in the afternoon. Of course that was official. An armband with the star. Jews were not allowed to travel by train, but I had some sort of slip saying that I worked at the sawmill, so I could go by train. In the meantime, my father worked all the time in the woods.

In addition to that we had extra jobs, for what we were paid was not enough to get by. My father took jobs overtime. For example, one of the Jews said that he needs 3 square meters of wood chopped for the winter; they didn't use much coal over there. We would have two or three days of work this way. I did everything with my father: sawed, piled, chopped into small pieces. And we were paid for that. Another Jew came: he needed his garden dug. So we went and did the whole garden.

For the local Jews in Niepolomice, who had lived there since before the war, nothing changed in their conditions except they had to wear the armband. Otherwise, they continued with their businesses. The head of the Judenrat 24, Artur Mames, had a store on the Niepolomice town square, selling iron and farming tools. He had it until the deportations in 1942. The German authorities did not interfere with such affairs. The real danger was still ahead of us, but we couldn't have known that.

Of course we took advantage of the Jewish kitchens, because the money we made was not enough, one couldn't survive on that. I was no longer a small child, already 16, but somehow I was included among the children and both my sister and I were taken in by different Jewish families. My sister was with an elderly couple; he was a furrier. She got lunch and dinner. I was with Mr. and Mrs. Moszajn. I don't know where they were from: such a well-to-do Jew, even if exiled from somewhere else. He must have had some jewelry, I don't know. They also lived in a rented apartment, but they had two rooms and a kitchen there and I went there for lunch and dinner.

The Judenrat organized this action. My father went to President Mames and said that we had escaped from Cracow, that we were left without anything of our own, and the President gave us a card for two meals a day. My father was there with me, and he said, ‘Mr. President, this is my son, but I also have a wife and a daughter.' ‘There are no more cards left,' the President said. ‘You have to share those you got.'

My mother helped in a kitchen, peeling potatoes and the like. And she did something not called for by the Ten Commandments. My mother lost a lot of weight. She had a belt tied tight around her waist, and when she was peeling potatoes and nobody was watching, she would drop a potato in the place of an imaginary breast, for she hardly had any breasts any more, poor thing. I mean, she did, but very thin. She would bring five or six potatoes from such a peeling session. I would bring two pieces of bread and my sister did, too. We basically didn't eat at the house of the people who fed us. We got one meal and for the other they gave us sandwiches, we thanked them and took them with us.

That's how the first two years passed. The summer of 1942 was very hot. In Berlin they made a decision about the final solution of the Jewish problem 25 and it applied to us. The mayor announced that all Jews in Niepolomice are to gather on the town square on a certain day, until a certain hour 26. The mayor of Niepolomice selected around ten farmers with carts. Nobody took their furniture, only a small sack with valuables. It was summer, but people took their coats. At the time, Wieliczka [a town in southern Poland, 15 km east of Cracow] was the district town and Niepolomice was part of that district. All the Jews from the district were to gather in Wieliczka on the appointed day. It got terribly crowded in Wieliczka that day.

The town was around 12 kilometers from Niepolomice. We walked on foot, two hours or even four, but that didn't matter. A few sick people were thrown on the carts, the rest had to walk. I think two navy-blue policemen walked with us. Nobody ran away, nobody shot. Everybody was depressed, for we didn't know where we were going and what would happen. Wieliczka was in chaos; suddenly hundreds of people appeared at the office.

On the next day an announcement was made that all Jews were to gather on the square by the sawmill, so we went to that square. A side-track of a railway was there. When we walked into the square it was already full of Germans. I don't know, they had all kinds of different uniforms, SS, SA, who knows what they were. The first selection took place there. All persons visibly handicapped were not allowed into the square. They were shot on the spot. We didn't see that, but we heard it, for the small grove was close by and one could hear everything happening there. We knew they were not shooting in celebration, that those people were murdered.

The whole place was surrounded by all kinds of police, German and also Polish, in groups of ten. Ten times ten makes a hundred. Then a break and another hundred. I remember, it got embedded in my memory, that there were six rows like that, which makes for 6000. It was a scorching hot day, but everybody was wearing a coat, some were wearing a sweater, some two sweaters. For we were allowed to wear only 5 or 10 kilos worth of clothing. Everybody had a little saucepan. We had them, too, for my father said we each should have one. My father had 60 zlotys. He gave us each 15, in case we got separated. Those are terrible things.

After a few hours they allowed us to sit down on the grass in this square. Some committees passed by or something like that. They walked past us and pointed to some rows. As it later turned out, they were singling people out. They pointed a finger and asked, ‘How old are you?' I said 18. My father, a 46-year-old was of no interest to them. We didn't know it then. [On 27th August a selection was made: the young and strong were taken to labor camps, the older men, women and children were to be sent to the Belzec extermination camp.]

We stepped out of a row, the selected ones, and we were moved to the side. There were over six hundred of us. We were allowed to say good-bye. I won't describe that because I can't. It was one great wail, that square. Thousands of people. Torn apart. This is terrible. That was the end, really. I never saw my family again.

Later a freight train was brought in. They were loaded onto the train. It was summer, hot, they were packed into locked cars. We were taken away. First the families went to the trains; we only saw how they walked, then the doors were closed and that was the end. And us, the selected 600, maybe 650, were taken back to Wieliczka.

We were put in some garage, a room with concrete floor, walls and roof. The concrete was not too terrible, because it was summer so nobody got cold. They kept us there for three, four , maybe five days. The local Jews from Wieliczka had connections. The guards around us were the Polish navy-blue police. Once in a while someone would be brought in who was caught on the street and who was trying to hide somewhere. Though most were shot immediately. Two or three times they came to take twenty young men from among thus. When the men came back they told us what they did. They were taken to the cemetery, where the Germans took the Jews they caught. Some of them had been in hiding; others had been taken in by someone who got scared the next day and said, ‘Go away, Jew!' or who simply wanted the money. Those were terrible scenes.

I can tell of one such case. A Jew from Gdow, who was brought to us, had hid his wife and children in a safe place. Or so he thought. But his wife and children were brought to the cemetery and shot in front of him. He threw himself into the grave, but the other prisoners pulled him back. Later he died anyway, in Rozwadow. After a few days they loaded us onto a train and we went.

We traveled for something like two days. We thought we are already in the Ural Mountains, in Siberia, but we were merely in Rozwadow [a small town in eastern Poland, around 100 km from Lublin] in the Kielce district. The doors of the car were thrown open, we heard them yelling, ‘Raus!' [German for ‘Out!'] and once in a while someone shot in the air. They were not shooting people, but they were shooting. Running, some of us lost what they had, a saucepan, a bag, a knapsack, or a sack. The soldiers were dressed in black trousers and khaki shirts with SS symbols. They spoke German but also ‘shibtsiey, yob tvoyu matc!' [Russian: ‘Faster, damn it!']. So we realized who they were; we called them ‘wlasowcy' [Vlasovtsy: Russian soldiers from the army of General Vlasov who passed over to Hitler's side]. Were they really from the army of General Vlasov, who supported Hitler? I don't know, but that's what we called them.

In any case, only one of them spoke German, an ‘Oberwachmann' [German: senior leader]. They were in charge of the convoy and I spent the first three months in Rozwadow camp watched by them. The camp commandant was Austrian, an SS-man, Josef Schwammberger. I went to his trial. In the camp there were two other SS-men, the others were Ukrainians, ‘wlasowcy.' The only nice thing about them was that they sang prettily in the evenings. [Schwammberger, Josef (1912-2004): a member of the Schutzstaffel (military protection unit) during the Nazi era. During WWII, he was a commander of various SS forced-labor camps in the Cracow district. From 1948 until 1987, Schwammberger lived in hiding in Argentina. In 1987 he was extradited to Germany. At his trial, which lasted nearly a year (1991 until 1992), he denied being guilty of the crimes of which he was charged. On May 18, 1992, he was condemned by the Stuttgart regional court to life imprisonment, which he was to serve in Mannheim. In August 2002, the Mannheim regional court declined a parole request. Schwammberger died in prison on 3rd December 2004. (Source: (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Josef_Schwammberger)]

We spent three months there. Enough for some of us to be starved and others shot, so that only 300-350 of us were left. It's there that I found out that the saying, ‘Before the fat one slims, the slim one dies' is false. It turned out that the fat one died before the slim one. The skinny ones were used to hunger and very primitive food. Sometimes I ate from the trashcan. Every day we walked five kilometers to work in steelworks in Stalowa Wola [a city in eastern Poland, around 100 km south of Lublin]. Every night several of our group were shot. A guard would call a prisoner and shoot him so that he fell on that side on which he was not allowed. There was roll call after and before going to work. A few were killed in one place, then a few in another, because someone didn't move fast enough or because someone else didn't get in line. There were a hundred pretexts. After about 3 months, several hundred people were killed.

One day, at the steelworks, they gathered us at the gate and organized a selection. They picked around 300 of the stronger, healthier looking ones. Those did not return to our camp, because a smaller camp was created for them right there at the steelworks. The group I was in went back to our camp and we spent two days there in fear, not knowing what will happen to us. Two, three days later a group of Germans came from the steelworks and once again we were gathered and looked over. They made us run, looked into our ears, mouths, I don't know why, and everybody tried to show he is a fit short-distance runner. I ran, too, for one thought: maybe I can save myself this way? But then, one didn't know what one would be saved for.

I found myself in the group of the chosen ones. They took us to the steelworks and a group of 100 or 150 Jews remained there. We were the better ones. For the rumor had it that those who stay in the steelworks will remain in the camp, while others will be sent to the Cracow ghetto. Some of the Jews paid to stay.

My life was saved because I worked in a team with a group of Poles. I was assigned to the smelting oven. Dirty work. I looked like a chimneysweep, because we mixed water with graphite. For some reason the team liked me. Obviously they didn't call me ‘Mr. Sokolowski' or ‘Leopold' but ‘Jew.' I became ‘our Jew,' the familiar Jew. Foreman Kuczynski was a simple worker and a decent man. He would often summon me, but not as a Jew. He didn't say to me, ‘You dirty Jew' but ‘you idiot,' ‘you so-and-so, what have you done,' for mistakes happened. But there was no nationalist hatred in that. In those men, I could feel pity.

The Poles got refreshment meals and we had our Jewish soup in the camp. When they ate, we stood around like beggars, each with his canteen. We watched them: maybe one of them will not eat everything? Someone would call, ‘Get over here!' and give one of us whatever he had left. One thanked and continued standing around: maybe there will be another? Once one of them even brought me four or five raw potatoes. Those were people of the peasant working class. They had a quarter or a half of a hectare of land and worked in the steelworks. Each of them went back home after work and came back every day.

So one of them picked four-five potatoes, selecting the bigger ones, and brought them over. There was control at the gate: ‘What are these potatoes?' He said, ‘I'm going to bake them; I like them baked.' This was a human impulse: ‘I'll take some for the Jew. He is hungry, I'll give them to him.' So he brought them and said, ‘Hey, Jew, here's some potatoes.' There were fires all over the steelworks, so there was no problem with baking the potatoes: in fifteen minutes I had them nice and crisp. This is what let me survive.

The manager of the steelworks, Pytel, a man with a thin black mustache and a brisk walk, was not a scoundrel. There were no conversations, of course, no way, but at night, during the night shift, he came to me and said, ‘Here's the key to my locker. There's soup and bread. Go and eat, only make sure nobody sees you.' That was a human impulse. Obviously, that didn't happen every day, but still.

Some Jews who were run into the camp were very rich. They'd leave their estate with a non-Jewish friend or neighbor and later, when they were in the camp they looked up another Pole who was willing to risk - and I would also give those people the medal of the Righteous Among the Nations 27 - and negotiated. The Jew would write a letter: ‘Mr. So-and-so, send us a 100 or a 1000 zlotys,' and the message would reach the Pole. The proportions were not very fair: 7 to 3. The Pole took 70 percent and the Jew got 30. The Jew would say, ‘Mr. So-and-so, bring me: two loaves of bread, a kilogram of sausage, half a liter of vodka.' The Poles would bring what was on the list.

In our camp, while I was dirty and hungry, others were not. Of course, they couldn't always manage that, but for example at Yom Kippur, they prayed, fasted and didn't go to work, which meant someone else, such as myself, had to go for them. They would say, ‘I'll give you a quarter of a loaf of bread and my soup and you go to work in my place.' So I went and worked 16 hours for someone else. Do people know that it was possible to go to work for someone else? That was possible in Stalowa Wola, where there were only Jews, the rich and the poor, and the camp commandant, Goldstein, was bribed. All guards were elegantly dressed in elegant old Jewish clothes, leather boots, when I wore pants made of paper. It wasn't plain paper, but the thick kind used for sacks. They were quite strong. I made my pants out of such sacks.

I worked like that for almost two years, from the end of 1942, until July 1944, eating once out of the trash, another time from under the stable, once I stole from pigs, for they gave boiled peelings to the pigs. When the eastern front was coming close, we were moved again. Some got away, for it was difficult to watch everybody closely. We were taken to Plaszow 28. I found two of my father's brothers there. It was terrible, meeting them. I didn't find out anything from them, because nobody could bear to talk. We spent a day and a night there, I think. My father's brothers brought me some soup and a piece of bread. I never saw them again.

At night they chased us to the train again and we went in an unknown direction. We got out in a very beautiful area. It was the vicinity of Gross-Rosen 29, in the Walbrzych district. They rushed us to the camp, and, as usual, there was roll-call; we had to undress completely, because they counted on some of us having money, gold or other jewelry on us, so they looked in all possible places. It was a camp for men only. After washing up they gave us a new striped suit and a number. We slept in a barrack. Everybody bent their knees, fitting into one another. The floor was strewn with wood-shavings for softness, and we slept like that one or two nights. Later they registered us according to profession. I heard the word ‘Schlosser,' ironworker, everywhere. There were 250 ironworkers and I among them. They packed us onto tractors. But we didn't go too far this time, only to Bolkow [a town in south-western Poland, around 100 km from Wroclaw]. There were two or three trailers attached to the tractor.

The camp was on the hill, and that was Bolkenheim. I think we were the first to be brought there, around 300 Polish Jews and 200-250 Jews from Hungary. At the time, the German occupation of Hungary had just begun 30. There was also a small group of Greek Jews: 20, 40, 50? It's hard to say how they got there, it was difficult to communicate. With the Hungarian Jews we could speak in Yiddish, for Hungarian could not be mastered. Conditions were hard over there, too. I worked as a turner at a lathe. I was not trained as a turner, but I learned fast. I was there from early fall 1944 till February 1945.

In February 1945, they evacuated us to Buchenwald 31. We got frostbitten in the death march 32. We walked through Szklarska Poreba [a spa in south-western Poland, around 120 km west of Wroclaw], in a column, surrounded by the SS. Those who couldn't keep up were shot and thrown into a ditch. Then they loaded us onto a freight train and we traveled for five days. That was February 1945. There were 65 people, fitting into each other sitting down, but in two or three days there was more space, for we pushed the bodies of those who died out of the car. Inhuman conditions. Those were abnormal times. After the liberation of the camp, the Americans transferred us to the buildings of the SS and organized provisional hospitals there. At last there was a white bed, a sheet, a mattress, instead of a bed of boards. I was still limping, had difficulty walking, because of the frostbite for which I had to have surgery.

I was terribly naïve. I thought that since the war was over, everything would be back to normal right away. It took me three months to get back to Poland, in July 1945, for when the Americans liberated us, I could barely walk. I had to stay in bed for 6 weeks, and couldn't walk at all. They took us to Forst [a German town, right on the Polish border] and we were met by the Polish army. The border crossing was in the village called Zasieki, 25 kilometers from Lubsk [a town in western Poland, around 70 km west of Zielona Gora]. And that's where they left us, in Lubsk, saying, ‘Go look for an apartment, for half of the Germans had run away from here. There will be sheets, pots and pans, everything.'

But me and five guys my age, 21, wanted to get to Zielona Gora [a city in western Poland] and Krosno Odrzanskie [a town in western Poland, 35 km north-west of Zielona Gora]. From there, one could take a train. But it's over 50 kilometers to Zielona Gora, over 30 to Krosno Odrzanskie and I had a part of my toe amputated because of the frostbite during the death march.

So I decided against it. I went to an army doctor, Bak, and asked, ‘Doctor, what am I to do now? I have no family; I haven't been able to find anyone. I have nowhere to go, really. Here at least I get some soup and bread every day. But I can't walk, so what kind of a future is that?' He asks, ‘Can you speak German?' I say, ‘Yes and no. I know a little Yiddish, that's a start. And I've spent almost the entire war with Germans so I can speak it, a little.'

The place was full of people who were repatriated from beyond the Bug [Polish citizens from the former eastern regions of Poland, forcefully moved west after new Polish borders were established at the Yalta conference], they couldn't even say ‘Guten Morgen.' So he says, ‘You know what, we are organizing a Polish hospital. There are Germans on the ground floor and only Poles on the first.' There was a doctor, German. I went with him on patient visits and translated a little. At this age one learns a language fast. For over a year I worked as a nurse, not a very well defined function, but I was first after the German.

When I was In Lubsk, I didn't know that a year after the war the Kielce pogrom 33 took place. How would I know? I didn't buy newspapers, I didn't read, I didn't care, I wasn't interested. I didn't know either about the pogrom in Cracow in 1945 34. Had I known, who knows what course my life would have taken. Later, when I was in the army, I had no contact with the Jewish community. I did meet Jews, for I wasn't the only Jew in the army. Some of them I recognized immediately, for example Major Orbach: not only his name but also his looks were telling.

I was in touch with an old acquaintance from before the war, a Jewish woman, Wadelis. When I was stationed in Poznan, she suggested I can move in with them. Her daughter and my future wife were the same age, and they were best friends. So that was my contact with a Jewish family. Later I found out that Mrs. Wadelis was hoping I would marry her daughter, Edzia; I was a Jew, she liked that. But I knew them both and picked my present wife. I liked her a lot.

I wanted to be a doctor very much. I talked to Doctor Lipszyc, from Lubsk. I told him how much I would like to study, but that I had to make a living and had no base, no home. He said there were so-called academic companies in the army. For a year they prepared you for the final exam and those who passed signed commitment papers to the army, for 12 years, I think, and were moved to Lodz. In Lodz there was the Military Medical Academy. At the time it was called WCWM, Wojskowe Centrum Wyszkolenia Medycznego [Military Center for Medical Training]. One could study there and remain in the army.

I said, ‘Yes! Right away!' But he said there is one condition: not to reveal Jewish descent. So I said, ‘Doctor, I was scared for five years. Am I to remain scared for another five? You are a man, so you know. I am circumcised. I go to take a shower with the whole company and what? I cover myself, because I had it circumcised?' He said, ‘Somehow you have to manage.' So I said, ‘No, I'm not up for this, not now.' Because of that I didn't become a doctor. Though I liked that idea very much.

In 1947, when I was going to the army, a Russian officer, from Ukraine, Major Dymitrij Solopienko, says to me, ‘So where is your family?' I say that no one's alive. So he asks, ‘Are you Polish?' ‘Yes, I am.' ‘Do you have any family?' ‘No, nobody.' ‘So you won't reject your family, or hurt your father's, mother's, uncle's feelings if you change your name? If you have no close ties, why should you have a German name when you can chose a Polish one? In the Soviet Union where I'm from there is no anti-Semitism, but in Poland some of that still remains. Why should you have a bad start just because you're a Jew?'

At my level of awareness at that time, these were all convincing arguments. So I said, ok, I won't hurt anyone's feelings, I'm alone in the world. Had I been a son of some count... Why not Sokolowski. I came up with Sokolowski just like that: ‘S' would be such a nice letter to start your signature with. I was just a kid then. Only 22. He said, ‘Ok, that's done. We'll deal with the formalities later, no one should know here, and that's that.' And so I became Sokolowski. Obviously later I formally changed my name at the registrar's.

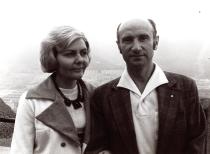

In 1948 I married a non-Jew, Gabriela Utrata. When one is 22 and comes to Poznan straight from military school, where was I to look for a Jew? Where would I find one? I was lucky, for my wife knows even less about Christianity than I do. She was raised by the communists. I have great respect for that. My father-in-law, a carpenter, was a member of the KPP 35, and my mother-in-law was also active in the communist movement. They didn't go to church, but they used to send their daughter, that is my wife, to a grandmother or an aunt. When she was in the countryside she was taken to church, maybe they taught her something, but she did not have a religious education.

I went out with her and after a few months I went to her parents to ask for her hand in marriage. My wife arranged that I'd come and we'd talk. I brought some flowers or some alcohol, I don't remember which. I introduced myself, and said that I came here - well, they knew I didn't come to look at the furniture, but to visit Gabrysia - because I had serious intentions. Therefore I should explain certain things to them. I don't have a family, I am alone, and I am a Jew, if they don't mind. My father-in-law just sat there, without saying anything, but when I said that I'm Jewish he reacted right away. He said, ‘Comrade Leopold, before the war I used to go to jail together with Jews, not to make any distinctions. I will be proud to have a Jewish son-in-law!' So in this respect I found a good family.

I left the army in 1957, during army reduction 36. They reminded me that I was a Jew. As comrade Khrushchev 37 said, ‘There will be as many Jewish officers in the army as will work in the mines.' And since after the war I was not planning to work in either Polish or Belgian mines, I decided they can get lost; I had my pride, I left. During the next two years I could chose which school I want to go to and that's how I graduated from a vocational school for mechanics in Poznan, at Debiec. That became my profession. I went to college later, when I was already working.

In 1957, when I was less scared, I went to Folkssztyme 38 on Nowogrodzka Street in Warsaw and placed an ad in the paper saying that Leopold Federgrün is looking for his relatives. I got a letter from Aunt Sala from Paris. She sent me photographs which I could enlarge for myself. That's all I owe her. For these were not good people, even though she was my mother's sister. They found the only family member that survived and they didn't even invite me to France to come and see! Things like that shouldn't happen among Jews. My aunt and uncle came here. I went to greet them at the station with my wife, with some flowers. They were so surprised! She brought a sack of things, half of which she took back with her, embarrassed to even show them. She probably thought that some pitiful Jew in rags will pick them up and take them to a cellar, to some hole.

In March 1968 39 I was reminded thoroughly and emphatically where my place is. I am deeply convinced that I was the only Jew at the Poznan bearing factory where I worked. I was in the party leadership, I was one of the editors of the newsletter, I was a lecturer, for the factory organized foreman courses for qualified workers. I supplemented my meager pay. I had two children. I wanted to provide them with decent conditions. My wife did some sewing on the side, to add to what we had, and then I was told: ‘Leopold, we like you a lot, and respect you, but you have to understand. For the time being you won't be able to do the lectures.' Then the newsletter: ‘Mr. Sokolowski, you understand, we respect you, but...' The Party secretary said to me: ‘Leopold, if it was up to me, but there is nothing I can do about it. Please, don't come to the committee any more.' I thought that if we left Poland, the parents would be separated from their child and my wife was the only child. Because one could get a one-way ticket with no permission to return. They took away your documents.

I couldn't make that decision. I didn't want to. My in-laws were too decent for me to take away their daughter and leave them alone. So I decided not to go then.

I talked to my son [Ryszard] and I talked to my daughter [Renata]. My daughter was in high school. I said to my son, ‘So, what do we do? Shall we go?' But he said he doesn't experience anti-Semitism too much, doesn't really see it. He was a freshman at the Higher School of Economy. He said, ‘This is my first year in college. If I go abroad, I'll have to learn the language, and my studies, all this work will go down the drain. I wouldn't want that.' He was very close to his grandparents. My wife being a single child, my children were the only grandchildren. I really respected my father-in-law. He was twice offered the position of the director of a factory and he refused both times. He said, ‘I am a carpenter. I can be a foreman, a workshop manager, but nothing else. I don't have the education.' Many would take a directorial function, even if illiterate or semi-literate. But not my father-in-law. He was a modest man. He never wanted anything for himself. He had two rooms with a kitchen. Kazimierz Utrata was a very decent man. Others have plates at the cemetery saying, ‘In sacred memory of...' My father-in-law's sign is terse: ‘Committed Activists of the Workers' Movement: Kazimierz Utrata, Maria Utrata.'

Obviously it is difficult in a mixed marriage to keep up either Jewishness or Christianity. That is why my son has been raised without religion and so was my daughter. My daughter joined a Catholic family, because she fell deeply in love with a boy who was, and still is, a strong believer. They have a good marriage, which has lasted already 30 years. My son's marriage is a little longer: 32 or 33 years. My son is an atheist, my daughter's house is Catholic and we participate in different events at both. We even participated in one Christmas Eve. We usually go away for the first or second day of Christmas Holidays. When we were over there at Christmas, my son-in-law read something from some Bible. He tolerates me. He knows his father-in-law is a Jew and has nothing against that. Very well, then I have nothing against him. He was raised like that; it's his right.

My dreams came true and I went to Israel twice. I was an active member of the Jewish Veterans organization 40. I am a member of TSKZ 41, but I've stopped going there. Nobody wants anything from me and I don't want anything from anybody. And I am very aware, even if I still want to live very much, that I am ending. Recently I lost 10 to 12 kilograms. I'm not naïve, I know what that means. I don't know, maybe I'll live a year, maybe five? That's what my life is like.

Right now I am somewhat sensitive, maybe oversensitive on the issue of anti-Semitism. When I read newspapers or watch the news, that's what I'm looking for. It's a complex, unfortunately. I've suffered too much for being a Jew. The Germans call it ‘der Zeitzeuge,' witness of history. But I say, I'm not a witness of history, I'm history's active participant. I haven't stood on the side watching people suffer, but I suffered, too. I haven't read about someone getting killed, but my family was murdered. But I don't have a feeling of hatred and I don't mind German.

I am a member of the Jewish community to keep up the tradition. I revealed that I can read Hebrew texts, so I can read the Sabbath prayer in the synagogue. I am oversensitive when it comes to anti-Semitism. I married a woman I loved. I still love her, but the love of an 80-year-old is different from that of a 20-year-old. I have two children whom I love very much and who are good to me. I have grandchildren: 5 grandchildren and one great-granddaughter. And I am 81. It's my last stage. I can't reproach myself when it comes to my life.

1 KuK (Kaiserlich und Königlich) army

The name 'Imperial and Royal' was used for the army of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, as well as for other state institutions of the Monarchy originated from the dual political system. Following the Compromise of 1867, which established the Dual Monarchy, Austrian emperor and Hungarian King Franz Joseph was the head of the state and also commander-in-chief of the army. Hence the name 'Imperial and Royal.'2 Rashi

Full name: Rabbi Shlomo Yitzaki (1040-1105). He was one of the greatest Bible scholars in Jewish history. His commentaries on the Torah and the Talmud are indispensable for those interested in studying Jewish literature. He was born in Troyes (France), and studied in the two famous yeshivot of the time, in Mainz and Worms (today Germany). In 1070 he founded a school that made France the center of rabbinic sciences for a very long period. This school gave room, among others, to his sons-in-law and grandsons, who were also renowned Bible scholars and founded the Tosaphist School, and their commentaries are an organic part of any Talmud edition today. Rashi wrote commentaries on almost every scripture book, and commented almost the entire Babylonian Talmud. His commentaries had such importance that the first book printed in Hebrew was made on basis of these commentaries. The letters used for this purpose have been called Rashi letters since then. According to tradition, he died while writing the word 'tahor' (pure) in the commentary he was writing on the Talmud Makkot tractate. He died on 29th Tammuz; the location of his grave is unknown.3 Kazimierz

Now a district of Cracow lying south of the Main Market Square, it was initially a town in its own right, which received its charter in 1335. Kazimierz was named in honor of its founder, King Casimir the Great. In 1495 King Jan Olbracht issued the decision to transfer the Jews of Cracow to Kazimierz. From that time on a major part of Kazimierz became a center of Jewish life. Before 1939 more than 64,000 Jews lived in Cracow, which was some 25% of the city's total population. Only the culturally assimilated Jewish intelligentsia lived outside Kazimierz. Until the outbreak of World War II this quarter remained primarily a Jewish district, and was the base for the majority of the Jewish institutions, organizations and parties. The religious life of Cracow's Jews was also concentrated here; they prayed in large synagogues and a multitude of small private prayer houses. In 1941 the Jews of Cracow were removed from Kazimierz to the ghetto, created in the district of Podgorze, where some died and the remainder were transferred to the camps in Plaszow and Auschwitz. The majority of the pre-war monuments, synagogues and Jewish cemeteries in Kazimierz have been preserved to the present day, and a few Jewish institutions continue to operate.4 . Zbaszyn Camp

From October 1938 until the spring of 1939 there was a camp in Zbaszyn for Polish Jews resettled from the Third Reich. The German government, anticipating the act passed by the Polish Sejm (Parliament) depriving people who had been out of the country for more than 5 years of their citizenship, deported over 20,000 Polish Jews, some 6,000 of whom were sent to Zbaszyn. As the Polish border police did not want to let them into Poland, these people were trapped in the strip of no-man's land, without shelter, water or food. After a few days they were resettled to a temporary camp on the Polish side, where they spent several months. Jewish communities in Poland organized aid for the victims; families took in relatives, and Joint also provided assistance.5 Zionist parties in Poland

All the programs of the Zionist parties active in Poland in the interwar period were characterized by their common aims of striving to establish a permanent home for the Jews in Palestine, to revive the Hebrew language, and to further political activity among the Jews (general Zionist program). They also worked to improve the lot of the Jews in Poland, and therefore ran at the Polish elections. In the Sejm (Polish Parliament) Zionist parties gained 32 of the total 47 seats won by the Jewish parties in 1922. Poalei Zion, founded in 1906, and divided in 1920 into Left Poalei Zion and Right Poalei Zion, represented left-wing views. Mizrachi, founded in 1902, united religious Zionists with a conservative social program. The Zionist Organization in Poland advocated a liberal program. Hitakhdut (Zionist Labor Party), established in 1920, combined a nationalist ideology with a socialist one. The Union of Zionist Revisionists, set up in 1925 by Vladimir (Zeev) Jabotinsky, sought the expansion of its own military structures and the achievement of the Zionist movement's aims by force. The majority of these parties were members of the World Zionist Organization, an institution co-ordinating the Zionist movement founded in 1897 in Basel. The most important Zionist newspapers in Poland included: Hatsefira, Haint, Der Moment and Nasz Preglad (Our Review).6 Mizrachi, (full name

The 'Mizrachi' Zionist-Orthodox Organization): A political party of religious Zionists, which was created in order to build a Jewish nation in Palestine, based on the rules of the Torah. The name comes from the words 'Ha-merkaz ha-ruchani', that is 'spiritual center.' It was created in Vilnius in 1902 as a branch of the World Zionist Organization. In 1917 Mizrach broke off from the Organization as a separate party. Headed by Joszua Heszel Farbstein, other activists included Izaak Nissenbaum and Icchak Rubinstein. The Mizrachi party cooperated with the Zionist Organization in Poland, supported the program of national-cultural autonomy, took part in parliamentary and local self-government elections. Mizrachi also created its own school organization Jawne and youth organization Ceirej Mizrachi (Mizrachi Youth) and He-Chaluc ha-Mizrachi (Mizrachi Pioneers), later Ha-Poel ha-Mizrachi (Mizrachi Worker). Mizrachi's influence was strongest in southwestern Poland. After WWII it was the only religious party which was allowed to operate. Dissolved in 1949.7 Hashomer Hatzair in Poland