Zsuzsa Kobstein

Budapest

Hungary

Interviewers: Dora Sardi, Eszter Andor

I was born in the winter of 1920 in a hospital in Budapest. My parents

lived in Pilisvorosvar. It was such a cold winter that my father couldn't

get to Budapest. So, a telegram was sent to him saying, "Zsuzsa is born."

My father was also born in Pilisvorosvar in 1876. He was called Lipot

Maszler. He was an only son. His parents died before I was born. I don't

know anything about them. My father had another wife, but she died in

childbirth in 1916. Some time after that, he went with a friend to a dinner

with my mother's family. My mother and her sisters and brothers and her

parents sat on one side of the table and my father on the other side. My

mother sat across from him. When dinner was over, my father asked my mother

to marry him. They got married shortly after, in Obuda, and moved to

Pilisvorosvar. They lived in the house my father inherited from his

parents.

My mother, Margit Krausz, was born in 1890. She had 10 brothers and

sisters. My grandparents were quite religious, but my grandmother didn't

wear a shaytl. My grandfather had two kosher butcher shops in Obuda, but I

don't know where. I never saw them. One of my uncles also became a kosher

butcher. Sewing runs in the family. Three of my mother's relatives were

tailors or dressmakers, and Mother also loved to sew and do needlework. All

her brothers and sisters lived in Budapest, so they all survived the

Holocaust. We used to get together for big family occasions, but everybody

celebrated Jewish holidays separately in their homes.

Our house was on the main street of Pilisvorosvar. It was nicely furnished.

We had two big rooms, a kitchen and a huge garden. In the winter, we only

used the bedroom where we had heat. But from spring to autumn, we spent a

lot of time in the garden. We used to do our homework there and play with

other children from school and the neighborhood. We had Christian friends

as well. There wasn't this hatred at that time, in the 1920s. We got on

well with the Christians. We met our Jewish friends on Saturday in

synagogue or in the garden of the synagogue. My headmaster came to see

Mother often, and they would chat and my mother would teach her various

tricks in needlework. Our Christian friends invited us and my parents over

at Christmas to look at their Christmas tree, and they would send us a live

chicken for the holidays. My mother would send them matzot at Pesach.

My father worked as a business agent in the local coal mine. His job was to

collect orders from Budapest. My mother didn't work. She looked after us

and kept the household. She had a young Christian servant. Mother did a lot

of needlework, and she made most of our clothes.

My father went to synagogue every Friday, but on Saturdays he had to work.

But if he was free on Saturday, he went to shul and took us along. My

mother made challah on Friday and she taught us how to light the [Sabbath]

candles and what brochas to say. I still remember some of them. My mother

also made cholent, and we girls had to take it to a nearby Christian baker

and bring it home for Sabbath lunch. Many Jews did the same in

Pilisvorosvar. Every Saturday night, somebody from the community went

around to the Jewish families and told them where they could buy kosher

meet. So, the next day my mother would go and buy meat for the whole week

and put it in ice in the cellar to keep it fresh. We raised chickens at

home, and we would take some to the shochet every week.

We didn't go on holiday, but we often went on excursions on the weekends.

Sometimes all of us went, but often only my sister, I and my father went,

and Mother stayed at home. She would do some needlework and socialize with

her friends. My father was on very good terms with the local rabbi and the

Jewish pharmacist, and they would often pop in to chat with him.

My sister and I went to the local elementary school. It was a mixed school,

with Jews and Gentiles alike. We often went on excursions with the class

and we had many friends from school who came to play with us in our big

garden. It wasn't an Orthodox community, so we went to school on Saturday

and even wrote on that day. After elementary school, we went to the middle

school. But I only went for two years. I became very seriously ill and I

spent a long time in hospital and sanatorium.

When I recovered, I learned to sew. I became an apprentice in a little

dressmaking salon in Budapest and I worked there for two to three years.

Then, one day, my mother saw an advertisement in the newspaper from the

Berta Neumann salon. She went to see the owner and asked her to take my

sister and me on as dressmakers. We worked there until the German

occupation of Hungary.

We made beautiful dresses at the Berta Neumann salon, in the center of

Pest, for countesses and famous artists, like Katalin Karady. We had to get

up at 5 every morning and leave at 6. The train arrived in Nyugati station

at half-past 6. From there we took a tram and then walked. We had to change

into our elegant working clothes - a blue gown with a white collar. At 8

sharp, the manager of the workshop said: "Young ladies, it is time to

start." At half-past 9, the first table could take a break for 10 minutes.

Then the next table. We worked until 1 and then we had a two-hour lunch

break. The girls who lived outside Budapest brought their lunch with them.

There was a small stove and we could heat our lunch on it. In the summer,

we went for a walk during the lunch break or we sat in the Gerbeaud, a

patisserie. Then we worked until 6; we arrived home around 7. We envied

those who lived in Pest because they could go to the movies or go out. We

had to go home to Pilisvorosvar.

In 1942, the doctor told my parents that we should get out of the house in

Pilisvorosvar because it was bad for my health. This is why we moved to

Budapest. Mother went to see the rabbi of Obuda and asked him to give us a

flat. We got a one-room flat in the community building, which also housed

the Jewish elementary school. The rabbi arranged for my father to work in

the community. We enjoyed living in Budapest. For the first time since we

started to work in the Neumann salon, we didn't have to get up so early and

we had free time to go to the movies after work.

There were 50 to 60 girls in the workshop, many of them Jewish. But we had

to work Saturday mornings as well. We got our weekly pay at the end of the

workday on Saturday. On my way home, I'd buy candy, and I would give my

salary and the candy to my mother. After the German occupation of Hungary,

and only three days after a fashion show in the salon, it was confiscated,

together with the dresses, machines - everything.

I met my husband, Odon Kobstein, in our building. He and some other Jewish

boys who were in forced labor units were put up there for the night. During

the day they worked in a factory near Budapest. They would often come and

talk with us, and they helped us move to the cellar when there was an air

raid. In July 1944 as we were preparing to celebrate my mother's birthday,

she said to me, "We will make a big celebration, my dear." I asked her why,

and she told me that I would be engaged to Odon. He already had asked my

parents for my hand. I was very happy, but I didn't want to get married

yet, because we had nowhere to go.

When the Hungarian fascists took over the power in October 1944, we were

taken to the brick factory of Obuda. The older people were later sent off

to the ghetto in Pest, and we young people were marched to one of the train

stations, crammed into wagons and sent off to Ravensbruck. We arrived at

the beginning of December and stayed there about 5 weeks. Then those who

were in a condition to work were taken to the Messerschmitt factory. My

sister and I worked in the turnery until the middle of April. Then we were

deported, weak and ill with typhoid, to Mauthausen, and we were already

standing in front of the gas chambers, naked, with the dog tags around our

necks, when somebody came running and shouting, "Hey, Hungarians, we are

liberated!"

After our liberation, we spent three months in a hospital in Guzen. We left

the hospital when the Russians took it over from the Americans. We arrived

home in the summer of 1945. We found our parents in the old flat in Obuda.

My dear husband, my fiancé at that time, visited my parents every Sunday.

We arrived on a Sunday and he opened the door. "Zsuzsa," he said, "Where

have you been?!"

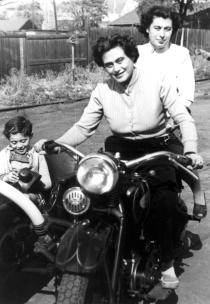

We married in 1947. We did not have a religious wedding, only a civil

ceremony. We moved into a small flat in Budapest and we found a small place

to set up a mechanics workshop. It was never nationalized because it was

small and we had no employees. My husband repaired only three things:

motorbikes, bicycles and sewing machines. At first, I wanted to go back to

dressmaking, but he asked me to help in the shop. So I was there all day,

and I used to sew. When people came in, they asked me if I would make

clothes for them as well. But I told them that I only sew for my husband. I

could never have any children because of the illness I had as an 8-year-old

child. But my dear husband told me that he loved me all the same.

My sister Judit married in 1948. She has a son, Gyuri. When he was at

university, he went to Japan to study Chinese and Japanese, and he never

came back. He lives in Australia. But he comes quite often and he also

calls me.