Susanna Sirota

Kiev

Ukraine

Interviewer: Ella Orlikova

Date of interview: August 2003

Susanna Sirota is a very pleasant, energetic old lady, though it’s hard to call her an ‘old’ lady. She lives with her husband in Pechersk district in Kiev, one of the oldest and most beautiful districts of Kiev. Her spacious two-bedroom apartment of 1950s design is very clean. She has kept the furniture, carpets and crockery, bought in the 1960s, in very good condition. The white furry cat, the hostess’s favorite, is ‘master’ of the house, undoubtedly. There are many books in the house: Russian and Ukrainian classics and modern and historical literature. She is fond of new publications about Kiev and Jewish residents of Kiev published recently. Susanna and her husband are very hospitable. They have freshly made pies to treat their guests. Susanna has a very educated manner of speaking. She used to work as a guide and she is always eager to tell more details about things.

My family story

Growing up

During the war

After the war

Glossary

I come from Priluki, a quiet town in Poltava province [200 km from Kiev] on the bank of the Uday River flowing into the Sulah River that flows into the Dnieper. Once it used to be a navigable river, while now it is a clean, picturesque river buried in sedge and cane plants. The town was buried in verdure. The water was of the best quality and even now fruit and vegetables growing in the town taste different.

There was a big synagogue with a huge dome, a very interesting building. In the 1930s the Soviet authorities closed it down like all other religious establishments [during the struggle against religion] 1. After the Great Patriotic War 2 it housed a cinema theater and in 1989 it began to operate as a synagogue again. There was no specifically Jewish neighborhood in the town. The Russian, Ukrainian and Jewish residents were good neighbors and got along well. Jews were tradesmen and craftsmen. The only pharmacy in the town was Jewish and there were Jewish doctors and teachers in the town. [Editor’s note: It was a place with a significant Jewish population. According to the census of 1847 the Jewish community consisted of 1007 people, in 1897 there were 5722 Jews.]

My grandfather Aaron Sirota, my father’s father, was a bookbinder. My grandfather was born approximately in 1867. I don’t know where the surname of Sirota came from. We were the only family with this surname in the town. My grandfather came to Priluki from Zhytomir. I don’t have any information about his family or why he moved to Priluki. I don’t know exactly when my grandfather got married, but I think it happened before 1890. I am sure he had a religious wedding.

My grandfather was religious. He prayed with his tallit on and he had a mezuzah at the entrance to his house. He touched it every time before entering his home. My grandfather had a seat of his own at the synagogue where he went on Saturday and all holidays. My grandfather studied in cheder and knew Yiddish and Hebrew. There were many religious books in his house. He cherished them, kept them on a special shelf and didn’t allow anybody to touch them. There were Russian classic books in the house as well. Everybody could take and read them, but not Grandfather’s books.

I’ve never been in the bookbinder’s shop where Grandfather worked. I don’t even know whether my grandfather owned it or worked for a master. Since my grandfather had this profession he was well-read and understood that the main wisdom was to let other people live their life. My grandfather spoke Yiddish to my grandmother at home, but he also had fluent Ukrainian, the main language of communication in Priluki. Grandfather Aaron died in 1930, when I was seven. He had spent almost a year in a ‘yellow house’ – this was how we called a mental hospital in our town – before he died.

My grandmother Nechama was a few years younger than my grandfather. She was born around 1870. She was a beautiful and kind woman. She collected clothes from wealthier houses taking them to poor families. I don’t know where my grandmother studied, but she was a well-educated woman. She had fluent Ukrainian and her favorite book was ‘Kobzar’ [‘The Bard,’ a volume of poetry] by Shevchenko 3.

My grandmother and grandfather raised 13 children: ten were their own and three others were adoptive orphaned children. My grandmother was well respected in the town. Her Ukrainian and Jewish neighbors always came to ask her advice. My grandmother gave simple advice. She said that children should be raised in kindness, people should respect each other, that it is better to buy meat in the morning when it’s fresh and candy can be bought in the evening. Every day, but Saturday, she went to buy food products at the market.

On Friday evening all her children visited them. It didn’t matter that they were not religious. My grandfather always recited a prayer and grandmother lit candles. Then the family sat down at the table. Grandfather started a meal after reciting a prayer and everybody else joined him. Nobody was allowed to touch any food while grandfather was praying. The family was big and there was a big bowl of the first course and for the second course there were beans or something and if there was meat in the soup it was eaten for the second course.

My grandmother was a very good housewife. I can still remember that she cooked for two days on Friday leaving pots with food in the oven to have it still warm on Saturday. At Pesach they took down special kosher crockery from the attic. There was matzah and many dishes made from matzah, but I don’t know whether they baked it or bought it from the synagogue. My grandmother didn’t attend the synagogue. It’s hard to say whether she was truly religious or just paid tribute to tradition, but on the outside everything was as traditions required. My grandfather and grandmother spoke Yiddish to one another and Ukrainian to their children and grandchildren and their Ukrainian neighbors.

My grandmother and grandfather had a house, if this is a proper word to call it, with a thatched roof that always leaked when it rained and they had to place washtubs to collect the leaking water. There was a hallway and a big room. All members of the family slept in this room and in the kitchen. There were ground floors in the house. There was a backyard and a few fruit trees, a dog and a cat.

My father’s sister Sureh-Rieva moved to America in 1912. She sent letters before the Great Patriotic War, but our family was afraid of corresponding with her. It was dangerous to have relatives abroad, particularly, in America. We didn’t have any information about her or her family. Later we tried to search for her through the Red Cross, but she changed her surname after getting married and it didn’t seem possible to find her.

My father’s brother Meyer was born in 1892 and was a worker at the book factory in Kiev. In the late 1930s he had an accident at work where he lost his arm and died. Meyer was single.

My father’s sister Manya, Galperina after her husband, was born in 1894, lived in Dnepropetrovsk in the east of Ukraine. She died in 1967. We lost track of Manya’s son Ilia and I don’t know whether he is still alive.

My father’s next brother Lev, called Buzia in the family, born in 1897, was a worker at the mechanic plant in Priluki. He joined the Party in 1924, when Lenin 4 died and numbers of people applied to join the Party. This movement was called ‘Lenin’s appeal.’ He had a Jewish wife and a daughter and a son, whose names I don’t remember.

During the Great Patriotic War he was in the underground during the occupation. The Germans captured him and shot him for his Jewish origin. Actually, he didn’t do much for this underground movement. He was killed during a mass extermination of Jews in 1941. His family managed to evacuate to Siberia with the mechanic plant, thank God. After the war they lived in Belarus. Their son served in the army in the 1950s. He visited here and we met several times in the 1960s. I know that Lev’s son has passed away and Lev’s daughter is old already. She is single and lives in Priluki.

My father’s third brother, Iosif Sirota, was born in 1905 and had a higher education. He finished Kharkov Higher Art College and was a good landscape artist. He lived in Kharkov [450 km from Kiev] in the east of Ukraine. At some time he was chairman of the association of artists of Kharkov. Iosif died in 1995. He had a wonderful family. They had three children. His wife died in the 1980s. His children, Elena and Semyon, live in Germany with their families. They emigrated in 1994, at the time when many Jewish families were moving abroad. Elena and her husband have a son, but I don’t remember his name. They are well accommodated in Germany, in Hanover. They don’t work, they live on welfare. Iosif’s younger daughter Nelly lives in Moscow.

My father’s third sister Esther, born in 1903, was single. She had a harelip from birth. She lived with her younger sister Polia. They were in evacuation in Omsk in Russia [1500 km from Kiev] during the Great Patriotic War. They stayed there after the war. Esther worked as a shop assistant, laborer and clerk. In 1958 Esther came to visit us for the first time after the war and died of a stroke before our eyes. We buried her in the Jewish sector of the town cemetery.

My father’s fourth sister Ehza, born in 1907, didn’t change her surname of Sirota after getting married. Her husband was a Jew. His last name was Krendel. They lived in Voroshilovgrad [present-day Lugansk, east of Ukraine, 400 km from Kiev]. Her only son Vladimir Krendel served in the army. He didn’t get any education. He didn’t want to study. I don’t know what he does for a living. He lives in Lugansk. Aunt Ehza died in 1987. Vladimir’s son, her grandson, lives in Israel.

My father’s fifth sister Polia was born in 1914. She was the most beautiful and my favorite aunt. Polia worked as a secretary in prison. Later she went to work at the stocking factory where she met a nice Jewish guy. He was a worker. His surname was Kostyl. They got married in 1937. They didn’t have a wedding party and it was customary at that time to have just a plain civil ceremony. Their older son Arik was born in 1936Their daughter Lena was born in 1938. Grandmother Nechama lived with Polia until she died.

When the Great Patriotic war began Polia’s husband was recruited to the army. He perished on the first days of the war. Polia, with her sister Esther and her children, evacuated to Omsk where they stayed after the war. Polia died in Omsk at the age of 78 in 1992. Her son also passed away, regretfully, and her daughter lives in Omsk.

There was another sister, born between Ehza and Polia, but she died in infancy. I don’t know her name. I don’t have any information about the adoptive children, either. They are said to have moved away. This was in the hard period of the Civil War 5 when it was difficult to track down people’s life.

My father’s brothers and sisters were not religious. They gave up religion in the 1920s following the trend of the time. Their families did not observe any traditions.

My father Avraam Sirota, the fourth child in the family, was born in 1895. My father finished cheder like the other boys in the family. This is all the education he got. My father was a painter. I remember how he climbed on the roof of the church. It was restored. It was hot and sweat was running down his face and he tied a kerchief on his forehead to protect himself from sweat.

My father wasn’t religious and he wasn’t an atheist. He just didn’t talk about this subject. He read many contemporary books. He considered himself an advanced Soviet man. He was very happy when he bumped into a Jewish surname in a newspaper. He showed me and said, ‘Look, this Jew is colonel and that one is a writer. It wasn’t possible before the revolution, you know.’ He was grateful to the Soviet regime for having equal rights and so were many others in his circle. My father helped and supported his brothers and sisters.

In 1921 my father went to order some medication in a pharmacy. He met Anna Ghivertz, a pharmacist. They got married shortly afterward. They registered their marriage in a registry office. They didn’t have a wedding party. It was a customary thing at the time. After they got married my parents moved to Lubny, 95 km from Priluki, probably looking for a job.

My mother, born in 1892, was an orphan and had no dowry, although her father Nathan Ghivertz lived in Priluki. I remember him. He was a fine looking, old man with a long beard, very handsome. When I saw him he was about 70 years old. They said before moving to Priluki he lived in the village of Ivanivtsi near Priluki. I don’t know how he earned his living there. He probably owned an inn or a shop. They say that at that time, in the 1900s, Nathan was wealthy and respectable. In the 1910s, probably trying to escape from pogroms, my grandfather and his family moved to Priluki. I don’t know what he was doing there.

His first wife, my grandmother, died at childbirth, giving birth to her third baby, my mother. I don’t even know my grandmother’s name. It is known that she died before she turned 30. She was beautiful and kind. The family has preserved a photo of her.

My mother didn’t like to recall her childhood. Probably, it was difficult. Her brother Isaac, born in 1887, and her sister Rosa, born in 1889, had Ukrainian baby-sitters, who taught them to speak Ukrainian and sang Ukrainian songs to them. I don’t know my grandfather’s second wife’s name. They had two more children, two girls, whose names I don’t know either. My grandfather’s children from his first marriage didn’t like their stepmother and played tricks on her. I don’t remember any details since the family didn’t talk about it.

It resulted in a scandal. My grandfather ordered his older son Isaac to leave the house. Sister Rosa and my mother Anna stood up for their brother. They left the house as well, but nobody called them to come back. Isaac reached Moscow after wandering for a long time. He drank a lot and bet at the racetrack. They even said about him that every horse greeted Isaac at the racetrack. He had a big family: a Russian wife and five children. Isaac died in 1940. Some of his children are still alive. We don’t communicate with them. One daughter lives in Israel.

My mother’s sister Rosa also reached Moscow. She married the director of a big bookstore in Moscow. In 1937, during the period of Great Terror 6, Rosa’s husband was arrested. I don’t know what the charges against him were, but he was sentenced to 25 years in exile and Rosa followed him to Siberia. They were not allowed to correspond and we didn’t have any information about them throughout these years. Rosa returned 20 years later, after her husband died in exile. She had many friends who were victims of Stalin’s terror. She visited us in Kiev and we went to see her in Moscow. Rosa lived over 100 years with a sound mind. Regretfully, she didn’t have children. She corresponded with Grandfather’s children in Kharkov.

My mother had to live on her own since the age of 14. She studied in a Jewish school for girls in Priluki, living with her aunt, my grandmother’s sister Esther. The families where my mother lived when she was a girl spoke Ukrainian and she didn’t learn spoken Yiddish and in her school she learned to read and write in Yiddish. My mother was not religious. At the age of 17 my mother became an apprentice of a pharmacist. This was a good profession, but it didn’t bring much money. My mother was poor and lived in a room in the pharmacy.

Another effort to resume family relationships was made when I was born in 1923. He gave me this Russian name of Susanna. This was a different name and my grandfather was a different man. This effort to make up failed and my parents didn’t communicate with him, although we lived nearby. I used to visit his house. They were wealthier than we. They always treated me to nice food. I don’t remember Grandfather Nathan ever praying. He had a small silk cap on his head. He spoke little and with me he only spoke Ukrainian. In 1929 Grandfather Nathan passed away. I wasn’t at his funeral, but I know that he was buried in the Jewish cemetery according to traditions. From then on my mother or I never went to his house.

I was born in Lubny in 1923. It was hard to find a job at that time. My mother’s older sister Rosa lived in Lubny at that period and my parents moved there. I don’t remember Lubny. After a short while we returned to Priluki. My first childhood memory is my brother’s birth. He was born in another room in our home. Everybody was excited and I contracted this excitement. The Jewish midwife told me, ‘if you suck your finger your mother will die.’ I never sucked my finger again. I liked my brother a lot when he was small. When he grew older we used to fight, but in general we got along very well.

My brother was born in Priluki in 1927. He was named Leonid and was called Lusik affectionately. Our family rented two rooms in a house with a porch. We had an entrance on one side and our Ukrainian landlords lived on the other side of the house. Later we moved to another apartment owned by Rachlin, a Jew. We lived there until the Great Patriotic War. Rachlin was a wealthy man and had a big family. Rachlin and his family lived in one house and he sold another house to somebody named Bodrak. We rented our dwelling from this Bodrak.

When the Great Patriotic War began Rachlin could have evacuated, but he didn’t want to leave his riches. He even offered Bodrak a lot of money to move himself and his belongings to a safe place, but Bodrak said, ‘No, whatever may happen will. If they shoot us they will shoot us both.’ They just couldn’t believe this was possible. The Rachlin and Bodrak families perished during the occupation. Rachlin’s old mother Bobele also perished. I remember that she went to the synagogue every Saturday and she asked my parents to keep her religious books in Lusik’s room.

My mother worked as a cashier in a store and my father picked up any job he could find: he worked as a loader or laborer. We went to a kindergarten. I can still remember the smell in it: it was so trite and I hated going there, but I had to. When I went to school I spent vacations in pioneer camps since they were free.

I went to school in 1931. There were 13 schools in Priluki: one Russian, two Jewish ones and the rest were Ukrainian. I studied in a Ukrainian school. There wasn’t even a discussion about it. I spoke Ukrainian and this school was near our house so I went there. Children and their parents could decide where to study or send their children. There was no nationality issue at the time. I had Jewish, Ukrainian and even one Belarusian friend, but national origin didn’t matter whatsoever. We had nice textbook. I remember the phrase ‘We are not slaves, slaves are not we.’

We prepared for becoming pioneers 7. It was quite a ceremony. There was a large photograph of our pioneer unit in the cinema theater where we were photographed wearing our red neckties. It meant a lot for us. There was an amateur art club at school. I sang well and I remember singing ‘Kalinka’ [Russian folk song] in the choir. There was also a noise instrument band where I played the castanets. I also attended the macramé, knitting and sewing club. We spent all our time at school. We studied the Ukrainian language, which was our mother tongue, and Russian literature and language. We had very good teachers. What we learned at school made the foundations for our future life.

In 1933 there was a famine 8. I remember my classmates fainting from hunger. My Ukrainian classmate and friend Vera Kalinichenko, whose father worked at a bakery, always brought me something to eat, always, while her hands were cold from hunger and I warmed her hands. People were like this: they were eager to help others as much as they could even when they were on the edge of death. They shared the little they had. She died in this same year of 1933.

My father worked at the grain supply company. He loaded grain with a spade and brought home whatever got into his boots. We boiled this grain. When mulberries and elderberries grew my brother and I used to climb trees eating these berries and then we had a stomach ache. My mother’s aunt Esther lived very well, there were a few families that managed better than others. I don’t know how they did it. It wasn’t proper to ask questions about such things. Perhaps, they had valuables that they could exchange for food. My brother was four years old and I took him by his hand and we went to visit them when we knew it was the time when they were to have a meal. When we heard their spoons clicking we went in and they gave us something to eat.

During the period of famine villagers from surrounding villages were coming to Priluki. They told their stories: ‘Communists came and took away everything. There was no food left, people were dying and buried in the yard where they lived.’ A woman and her daughter came to us from a village near Priluki. The girl’s name was Nastia. The mother returned to her village later and I don’t know what happened to her, but the girl stayed and lived with us before the war. She and I went to school together. When we evacuated in 1941 she stayed in our house to try to keep whatever belongings we had. There was a Torgsin store 9, but we had no valuables to exchange for food. I don’t know how we survived. We starved terribly, but somehow we managed.

However, we all strongly believed that those were temporary hardships and that life would improve. We believed we were the happiest children in the world living in the USSR, the country of equality and justice. We went to villages performing our concerts. There was collectivization 10, kolkhozes 11, everybody would work together and life would be wonderful!

We went to Kiev on tour and met with Postyshev 12, who spoke nicely to us, children of workers, thanking us for our devotion to the communist system. There was a New Year celebration and we were given candy in the house of pioneers [at present Philharmonic Theater]. It was a different world. There were only horse-drawn carts in our town while in this big city there were lights, cars, streetcars and asphalted roads. We believed that it would soon be the same in our town.

I remember the first radio transmission in Priluki. It was such an event! I remember the first bulb in the street and then power lines were installed in houses. We used to have kerosene lamps with wicks and made ink from soot. There were mute films, but then the first sound movie ‘Putyovka v zhizn’ [’Road to Life’] about homeless children who become decent Soviet citizens. Then there were other movies full of optimism and high hopes for a happy life: ‘Vesjolie Rebyata’ [‘Merry Fellows’] and ‘Tsirk’ [‘Circus’]. My father took us to the cinema. He liked movies.

Since my parents were not religious we didn’t celebrate any religious holidays. We only celebrated Soviet holidays and birthdays. My grandmother lived with Aunt Polia. My grandmother observed traditions, but she didn’t spread her views on the children. My grandmother bought or made matzah: I cannot say for sure. She always had matzah at Pesach.

We visited her to pay tribute to traditions. She told us about holidays, but we didn’t listen. We were atheists and learned at school that ‘religion was opium for the people.’ We thought my grandmother was so hopelessly obsolete, but we loved her, of course, and she loved her grandchildren. My grandmother died of old age in 1940. She was buried in the Jewish cemetery. I wasn’t at the funeral, but I don’t think there were any traditions or rituals observed.

It was a confusing period, but Stalin and Lenin were our faith, religion and god, if you want. I think that the first word any baby pronounced was Lenin and not ‘mama,’ so strong the ideology was. We didn’t have any doubts. I remember that our class tutor was arrested in 1937 [during the Great Terror] as a Ukrainian chauvinist, although she had nothing in common with them. Our teacher Pavel Yasinovski had a Jewish wife. She was sentenced to death, but nobody knows for what charges, and he followed her. The secretary of the district Komsomol committee and our teacher of drawing were arrested. It was a scaring situation, but we believed that innocent people could not be arrested and that if they were arrested, then it was the right thing to do. It was hard to believe that our favorite teacher, Maria Nikolaevna, was an enemy, but she was arrested as such. Well, then it meant that they truly did something against the Soviet power.

In 1938 I joined the Komsomol 13 believing that young people with advanced ideas had to be in the Komsomol. We were young, optimistic and enthusiastic. And, if there was a war to happen tomorrow we were ready to win a victory, this was what our favorite song said. I attended a sports school and was champion of Chernigov region in gymnastics. I tied my future with sports achievements.

I had a fiancé named Kolia Makarov. We had been friends for five years. He was one year above me at school. He was Ukrainian. This was my first love, I was 14. It was beautiful. We went to the cinema and to the park, did homework together, dreamed about a long and happy life together and kissed, but nothing else, God forbid. I still have a strong feeling about this wonderful sensation. In 1941 he was an infantry lieutenant. That we were of different national origin was of no importance to our parents. It didn’t matter at all. His parents had a good attitude toward me. I corresponded with him and in May 1941 his parents went to visit him in Belarus and took me with them. This was the last time I saw him. Kolia perished at the front in 1942.

I finished school on 20th June 1941. I took my championship certificate and went to enter the College of Physical Culture in Moscow. I arrived in Moscow on the morning of 22nd June 1941. Moscow was crowded at this time of the day. We got off the train and heard the word ‘war.’ I went to Aunt Rosa, my mother’s sister, living in Taganskaya Street. It was clear that I had to go back home where my mother, my father and my brother were waiting for me. Shortly afterward we received a letter that my father and other workers who were overage for service in the army moved to the Ural with their repair plant.

It was hard to get back. Priluki was in encirclement and the railroad was under continuous bombing. Trains went as far as Nezhin [75 km from Priluki], I didn’t have any money left and I showed my Komsomol membership card to get a ride on military trains and then I had to walk. I came to Priluki at night. Our window was open and I got inside through the window.

My mother said, ‘Why did you return? We cannot get out of Priluki.’ I don’t remember how we got this information, but we knew that Jews had to escape Germans. Kolia wrote his parents: ‘Don’t leave without Susanna.’ Kolia’s father was director of the mechanic plant. He was going to leave with the last train and take me with him. Aunt Esther said, ‘Look, you cannot leave your mother here.’ I said, ‘I shall not go without my family.’

The Makarovs took our family with them: my mother and brother Lusik who was in the fifth grade at school. Our trip lasted a month and a half before we arrived in the village of Darinskoye in Kazakhstan, 2400 kilometers from home. It was a big village on the Ural River. There was a Russian and Kazakh population and Ukrainians, who either arrived there during the tsarist time or escaped from collectivization. There were many people in evacuation, many Jews among them. There were no jobs and many people wanted to go to other places looking for a job.

I went to work at school as a physical culture [education] teacher having my championship certificate. I was also a senior pioneer tutor. My mother also took to any work she could get selling things or working as a cashier. The owners of the wooden house where we were accommodated lived in the upper part of the house and there was a man, his wife Vasilisa and their two girls living in the ‘podklet’ [basement, normally used as storage] in the lower part. They accommodated us in their room. I slept with the girls, my mother slept behind a curtain and Lusik slept with this man. We lived like a family and they treated us nicely.

My father was in Sverdlovsk in the Ural. We corresponded with him. He worked as a rigger at the Ural machine building plant. Since he was a worker he was not allowed to take his family with him. My father was mobilized to a labor army where workers were subject to military discipline living in barracks. Besides, they could be mobilized to the front line at any moment.

On the eve of 1942 instructors from a military unit visited our school. There were radio operators showing us how radio equipment worked. I got very interested in it and they taught me the Morse code: Dot-dash: dot is ‘ti,’ dash – ‘ta.’ Ti-ti-ta is ‘a’, tititita is ‘b’ and so on. I was so eager to get to the front to defend my Motherland that it took me no time to learn it. I was dreaming of meeting my fiancé Kolia. I always had this code tapping in my head.

By spring I finished my tractor driving training. I and another girl decided to walk to the district committee in the nearest town of Uralsk to ask them to send us to the front. They looked at us as if we were crazy. The local Kazakh population plotted whatever occurred to them to avoid the army service. They accepted us immediately. My mother didn’t mind. She wanted me to get out of that village. Later my mother realized that it was dangerous at the front. She walked with us trying to talk me out of it, but it was too late: we had taken vows. We volunteered to the front.

Since I had school education and knew Morse code and was a sports girl they sent me to a school of radio operators in Moscow. This was the Moscow School of Master Sergeant Radio Operators in Moscow region that was recently liberated from Germans. It was a school for girls and there were many Jewish girls in it. I enjoyed studying in this school and found it interesting. I was a head girl in physical culture classes and was an active student. We were hungry and ate heartily only when we were on duty in the kitchen once a month, but we were cheerful and joyful.

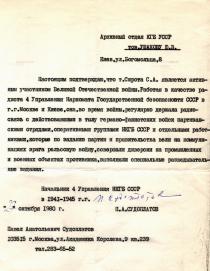

After finishing this school my friend Octiabrina Bondarenko and I were taken to a partisan school. She lives in Moscow now and we correspond and greet each other on holidays. We were taken to Moscow and accommodated in a hostel. It was like paradise: firstly, we were given enough food and then there were boys and girls of over 100 nationalities. There were Jewish students as well. It was a big school for radio operators, field engineers, intelligence and other partisan experts. Our big boss was Sudoplatov Pavel Anatolyevich. During the war he was chief of the 4th partisan department of the NKVD 14 of the USSR chief of intelligence service. [Sudoplatov, Pavel Anatolyevich (1907-1989): One of the leaders of the Soviet intelligence service, chief of various operations before and during WWII.]

We were taught to act in the German rear. We studied German very thoroughly. Later I got to know that our teacher, Emma Kaganova, was a Jew and the wife of Sudoplatov. Later we were accommodated in conspiratorial apartments. We were to learn to not get lost in a strange town, escape from shadowing, establish radio operations unnoticed and come to our apartment and leave unnoticed. It was as enthralling as a game, but when they began to teach us how to have a smoke or spend a night with an officer we got scared. I said, ‘I shall not go to the rear. I shall work in a partisan unit, but not in the rear.’

We cried all night through and in the morning we went to refuse. Only volunteers could do this work and we stayed in a partisan unit as radio operators. There was a group of eight of us and we agreed that wherever we went our common signal would be one eighth. We were sent to partisan units to establish communications or replace a radio operator. I went only once. They protected me fearing that the fascists would recognize a Jew in me.

We lived in Moscow and performed special tasks at a radio station. We were to receive signals from partisans and there was another station for sending signals. We were sitting at special desks listening for signals from partisans and those signals were very low.

This was summer 1943 when we had to do a landing task. I had some previous experience. When you are twenty you do not have fear. Things are just interesting. It’s easy mechanically: after a signal ‘tu, tu’ a hatch opens and you fall out one by one. The air current catches you and you lose your breath watching the ground coming closer. Many landed in wrong places: on high trees when it is impossible to cut off parachute slings or in the wrong location when you have to find your way by azimuth, but the most awful was to get onto the enemy’s ground. However, I got lucky. This was near the village of Volki, Priluki district. We were to transfer documents to a radio station, power supply for the radio and instructions. I stayed in a partisan unit for about a week.

I lived in a dugout with other girls. They didn’t know my name or surname or anything at all. Oksana Sizova was my code name. Everybody else had code names too. There were individuals who had to get to the town to establish communications and stay with an underground unit. Thank God I didn’t meet any acquaintances. Then one night a plane arrived to pick up the wounded to take them to Moscow. There were fires made to help it find the landing ground. I went back to Moscow on this plane.

I performed some tasks for Sudoplatov and stayed to work for him as senior radio operator. I was a radio operator of the highest category. By that time I became a candidate to the Party. This was the only way we knew we had to go: become pioneers, then Komsomol and finally party members.

In summer 1943 young guys came to our school. One of them was Lev Markelov, two years younger than I, born in Nizhni Novgorod in 1925. He was Russian. He told me later that he didn’t know the word ‘Jew’ before he met me. When they said ‘zhyd’ [kike] he thought that it was about a greedy and evil person, but he never associated it with national origin. Lev was very talented and in no time he grasped the specifics of our profession. He had sensitive hands and excelled in transmissions. We became friends.

Later, when the front was moving to the west and partisans also moved farther and they couldn’t be heard in Moscow, our center moved to Kiev in November 1944. When we arrived there was still smoke emerging from ashes. Lev was appointed manager of the radio station. Our facility was in Sviatoshino [district in the vicinity of Kiev at the time, now it is within the city]. We received a room at this radio station, but for some reason Lev had to give his overcoat for this. There were three of us living in this room: Lev, I and our friend Semyon. It wasn’t too bad since one of us was always on duty at work.

Radio operators received and transmitted code messages. We didn’t know their meaning. There were five symbols, space and then the next five symbols forming columns. The deciphering department was behind bars and nobody could get in there. They brought us coded messages for transmissions. The messages were signed ‘correspondent 102.’ We didn’t know the individuals. Even when they arrived we heard ‘the 102nd has come.’ They were intelligence officers, but we didn’t know them and they were different individuals every time.

We received a salary and food packages. We also received vodka at times. Markelov was promoted promptly. I was in the rank of lieutenant at the beginning and he had no rank, but then he was promoted to a captain. I liked him and then I thought that I was to get married some time anyway. I was 21 and he was 19. I knew from my mother’s letter that Kolia was gone and I also knew that I would never meet anyone like Kolia again. Our radio station arranged a great wedding party for me and Lev. We got trophy food products and trophy cognac left by the Germans.

I wrote my parents that I got married. They thought Lev was a Jew – for some reason the name of Lev was considered to be a Jewish name – and were very happy for me and I didn’t give them any details. Nationality didn’t matter to me. We had an official civil registration on 11th May 1945 after Victory Day 15. I remember that happy day of 9th May 1945. It was a bright sunny day and lilac bushes were in blossom. We were feeling happy and then we saw that there was a registry office where we were having a walk and we went in there and had our marriage registered. He kept his last name and I kept mine.

My parents returned to Priluki from evacuation. My father was in evacuation in Sverdlovsk working at a huge plant. He lived in a hostel and he never managed to have mother and Lusik join him there. My mother and brother moved to my father’s sisters Polia and Esther in Omsk in late 1942. Only in early 1945 my father reunited with them in Priluki.

Lusik was recruited to the army in 1945 and was sent to the war with Japan 16 where he was shell-shocked and became an invalid of the war. Later he went to work at the mechanic plant in Priluki where my deceased fiancé’s father Makarov was director. The Makarovs supported my parents. Later, when I became an officer in 1943, I sent Mother my certificate to receive monthly allowances.

In 1946 my son Valentin was born and at that time Markelov got a job offer to work in the embassy in Bucharest in Romania. Our baby was just a few months old and I was afraid of traveling with him and I went to my management to ask them to release me from this trip, but they said, ‘You can stay if you wish. We will find him another wife. Our troops there are more numerous than the Romanian population.’ While the documents were processed my baby turned eleven months and I had to go. My husband had a sensitive job receiving and transmitting messages. We had many impressions of our life abroad. It was a different world. We had everything we needed living in an embassy apartment. Our boy had nice food, clothes and toys.

This trip ended in 1948 and we returned to Kiev. The radio station already occupied our room in Sviatoshino. We received a big room of 28 square meters in the center of the city in a crowded communal apartment 17, on the fifth floor with no elevator. Our neighbors were KGB 18 employees. Each family, regardless of the number of family members, occupied one room. There were about five families residing in this apartment. There were three gas stoves in the kitchen, one bathroom and one toilet. There was a line to get to the toilet in the morning.

Our parents moved in with us and we partitioned the room with wardrobes and curtains. We got along well with the other tenants. When we got our first TV with a screen as big as a palm our neighbors came in to watch it even if it was time to go to bed or my husband had his work to do. Lev entered the Law Faculty of Kiev University. He was an extramural student.

After returning from Bucharest, where I was a housewife, I went back to work in the KGB. I was employed by a secret department fighting bandits. My work covered Western Ukraine annexed to the USSR in 1939 [cf. Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact] 19. There were gangs of banderovtsi [cf. Stepan Bandera] 20 in the woods. Our employees traveled there and I was to maintain communications with them.

At first it didn’t occur to me that the attitude toward me and my Jewish colleagues was changing. Once the former secretary of our party committee advised me in a friendly manner: ‘you shouldn’t mention anywhere that you are a Jew.’ And I said, ‘How can I possibly do this if it says in my passport that I am a Jew?’ Then somebody said that I should have kept my partisan passport in which I was Oksana Sizova, a Ukrainian. I was surprised and ignored those talks at first.

In 1948 Israel was established 20. On the one hand, I felt happy that Jews had their own country and our country supported it. On the other hand, I felt I was an ordinary Soviet citizen and this had nothing to do with me personally. Like cosmopolitans [Campaign against ‘cosmopolitans’] 21 that newspapers wrote about. I still piously believed in the ideals of communism and rightfulness of everything happening in my country.

In 1951 my second son Alexandr was born. Again there were diapers, feeding, all this prose of life. A year later I felt like going back to work and my mother was to take care of the children when I realized that all Jews were being removed from our organization. They didn’t announce any reasons and were firing people due to reduction of staff. But then it was impossible to get another job. I was one of the last Jewish employees fired in 1953, after this story with the doctors when there were no Jewish employees left in organizations.

As for the Doctors’ Plot 23, we believed at its beginning that it was true and that the Soviet power could not do the wrong thing. We thought that what happened was done rightly and if there was something wrong we believed that it happened because Stalin was not aware of it. However, looking at the surnames of those they denounced every day and finding out that most of them were Jewish names we felt uneasy. It couldn’t be true that only Jews were enemies of the people 24.

My husband was more than upset about it. He couldn’t understand how people could be mistreated or become suspects for the only reason that they were Jews. He was used to value people for their human merits. He lived in my family and my parents treated him like their son. Then Lev’s management called him. He was working in the KGB 1st department: work abroad, i.e., intelligence. They told him that he should either leave his family and continue working for them or quit. They told him openly that they were firing him for his connections with Jews. He quit.

Lev went to work as forensic detective at the Ministry of Internal Affairs. He received a very low salary. My father was a loader in an exhibition hall. He was responsible for handling pictures and it wasn’t hard, but he received a very low salary as well. I washed and cleaned our whole apartment and other tenants paid me for this work and my mother looked after the children. Life was hard from both the material and moral sides.

Stalin’s death on 5th March 1953 was a big private grief for us. My father, a very reserved man, was crying and crowds of people marched along Kreschatik [the main street of Kiev] crying. They had black and red armbands on their sleeves and it felt like an overwhelming horror of mourning. It was a great personal grief for me as well. Many years were to pass and I had to read many books and meet with many people to have the scales fall from my eyes and see the horror of this regime in a different light. I was a party member and it’s non-existent now. Only uneducated people still cannot believe in those crimes of Stalin and his retinue. My husband still believes in Stalin. I argue with him, but he doesn’t understand.

Another step to a more critical attitude toward governmental declarations was the denunciation of Minister of Internal Affairs Lavrentiy Beriya 25. It was impossible to believe that he was an ‘agent of international imperialism.’ It was another terrible lie on the highest level. Of course, he wasn’t an angel, but he was a devoted communist and the regime was trying to load its sins and evil deeds on him. He was publicly defamed and exterminated.

During the war our intelligence and partisan movement was in his hands and we wouldn’t have won the victory if it hadn’t been for him and other dedicated communists like Beriya. When we worked in Lubianka 26. I saw him several times though he used a different elevator than other employees, but one could meet him in the corridors. He greeted everyone and made an impression of an intelligent man. I heard about all these horrors about him in the 1990s.

It was impossible to find a job. I couldn’t even imagine how hard it would feel when you came to an organization and they said, ‘Yes, yes’ and you leave your documents and the following day, they tell you, ‘We apologize, but we’ve already hired a person for this position.’ It happened many times. I couldn’t imagine this was happening to me. I went to see the secretary of the party district committee and he pretended he was furious about it and said, ‘No, this cannot be true!’ He helped me to get a job as an accountant in a construction company.

I worked there several years until this company closed and I lost my job again. Once my former colleague, a driver, called me. He worked in the ‘Znaniye’ company developing manuals and said that I could work part-time as a typist. Since I was a radio operator and could transmit 140 signs per minute I went to work there. Later they employed me as a secretary and my knowledge of Ukrainian proved to be very useful. Here is the full name of this company: Association for Popularization of Scientific, Technical, Social and Political Knowledge. This was an ideological organization of the regional party committee. I was very grateful that my boss employed me without knowing of my Jewish identity. Later, when he found out the truth, he supported me and treated me with deep respect.

We invited the best experts in science, engineering, art and politics sending them to read lectures in various organizations. There were also guides conducting city tours in Kiev. Once my boss called me and said, ‘Get prepared to become a tour guide.’ I was confused and replied, ‘But I have no appropriate education.’ And he said, ‘Where there’s a will, there’s a way. Go listen to tours to get trained.’ I absorbed new knowledge and my colleagues used to say, ‘You are like a sponge absorbing new things.’

This was my revelation: Kiev, museums, the history of houses and streets. I found it all very interesting. I had to read a lot and shuffle mounts of books. To earn a kopeck [penny] one had to talk for a ruble and have knowledge for 100 rubles. Later I got an offer to become secretary of the presidium of the ‘Znaniye’ association that employed rectors of colleges and universities. I was responsible for taking minutes of the presidium once or twice a week. I actually worked at three jobs from 6am until late in the evening. I conducted tours in the morning, then worked as a secretary and then took to the presidium business. I became a popular guide and earned more than anybody else in my family.

My mother did the housekeeping and looked after the children. We put aside a certain amount of money for each day of the month for food. Sometimes there was no money left at the end of the month and then my father said, ‘I’ve made what we’ve never had.’ ‘What’s that?’ ‘Tea and bread and butter.’ My mother made nice pastries and I learned from her. We had gefilte fish, sweet and sour beef stew and later we began to cook pork stew as well. We didn’t buy matzah and my parents didn’t talk about Jewish holidays. We celebrated Soviet holidays: 1st May and October Revolution Day 27. The biggest holiday for us was Victory Day. Our fellow comrades visited us and we recalled the past days and sang songs of those years.

In the middle of the 1950s, my brother Lusik moved from Priluki to Kiev. He went to work at the chemical machine building plant ‘Bolshevik’ manufacturing huge vessels for the chemical industry. He worked there all his life. He was a fixing specialist of the highest category. I went to his workplace once and I saw that the unit where he worked was as big as two rooms. He earned very well.

He lived with us at first and then he lived in a hostel. When he got married he received an apartment. His wife Kylyna was a Ukrainian woman from a village in Poltava region. She was a nice person and we liked her a lot. Their daughter Lidia is 46 years old now. She is an accountant in the Ukrainian book publishing house. Her husband also works there. Lidia’s daughter Yulia finished a college and has a master’s degree. She is married and they have a child. She cannot find a job. My brother died four years ago. He had a heart attack and it was final. We keep in touch with his family.

My husband graduated from university and got promoted to chief of the militia department in the rank of colonel. He had his hard times. He worked at nights being a forensic detective. He captured criminals. There was a big case of counterfeiters, forgery of bonds. Unfortunately, he had to pay his cost for this job. This kind, decent and honest man began to drink. He still has this habit, though he is an old man now. My husband has always treated me and the children with love and tenderness, he is the head of the family, but of course, everything was done as I wanted.

We received an apartment in a new district of Kiev in the late 1970s. My parents stayed in the room in the communal apartment. Our boys studied at school. They were well aware that their mother, grandfather and grandmother were Jews, but they got no Jewish education. We didn’t observe any Jewish traditions and spoke Russian in our family. Our sons identified themselves as Soviet people. They don’t understand what it means to be a Jew. They don’t know any traditions. They don’t care about national origin and value personal merits. However, when they heard abusive words at school or in the street, whether addressed to Jews or gypsies [Roma] they would even fight against it. They are just boys.

My older son Valentin was very determined. He was good at studying foreign languages. In 1966, when he was a university student, he went to work as translator to Ceylon [today Sri Lanka]. He worked there for over a year. He graduated from university when he returned and went to work at the ‘Intourist’ company. He is deputy director of the ‘Bratislava’ hotel complex. His wife finished the Light Industry College and worked. Now she is a pensioner. Their son Vitali is 27 years old. He graduated from Kiev University and then went to an American college where he was sent for his successes in studies. He specializes in the banking business. My grandson is supposed to return to Ukraine by the end of this year.

As for our younger son Alexandr, we’ve had our share with him. He was a troublemaker. After finishing school he entered the Mechanic Faculty of Kiev University and was expelled when he was a third-year student. He missed classes having parties with his friends. Later he finished a hydromelioration technical school in Priluki, where he married Tania, a Ukrainian girl. Now he is constantly between jobs and has different ideas all the time.

In 1973 my mother died at the age of over 80. She had always had a weak heart. After that my father was paralyzed and bedridden for two years. We all attended to him. My father died in 1975.

We had a quiet life. We worked, went to the cinema and theaters. My husband was a football fan and often went to the stadium in summer. In summer we spent vacations at the seashore. We liked cruising down the Dnieper to the Crimea. It didn’t cost much. In the evening we enjoyed having a stroll in the park.

I visited my cousin Rosa in Moscow and she sometimes visited us. She talked about Stalin with such hatred. She said he was pock-marked and stood on a stool to appear taller. She spoke about his murderous crimes, millions of innocent victims and we were even afraid of opening our mouths. This was true, but we couldn’t believe it, this was the period of the late 1970s. She gave me forbidden books printed on cigarette paper, works by Solzhenitsyn 28, and gradually my conscience came to understanding that we had lived with such monstrous lies all this time. I began to feel offended that when they unveiled the monument in Babi Yar 29, the tour guides were allowed to say that there were over one hundred thousand deceased on this ground, but not a word about it that they were Jews. Kievites talked about it in whispers, but there was no official information about it.

Another example: I remember punishment for not having a job and this was evident suppression of a personality. I had an interval of 1-1.5 hours after conducting a tour and decided to go the cinema. Once they interrupted a film to check people’s documents to identify why they were in the cinema during a working day. They needed to have justification of their absence from work. This was terrible. They made a list putting down their comments and then they used to send letters to people’s work.

We were horrified about perestroika 30. We couldn’t believe that this avalanche of things published in newspapers and spoken on TV could have been possibly happening in our quiet lives. We felt some uncertainty. We, dedicated communists in the past, felt like criminals, but we didn’t know anything like this and lived a common life like everybody else. Big shots of party officials found their way promptly and became millionaires and the majority of the population became poor in a jiffy. They lost their savings. Our pension is not enough to pay for utility services, not to mention medications. When I see intelligent people searching for food leftovers in the garbage and eating whatever they find, I feel terrible. It was out of the question in the USSR.

A good thing about this period is the rebirth of the Jewish life. I never felt anything Jewish about myself, but when in the 1990s I heard songs in Yiddish for the first time I understood. I had spontaneous tears in my eyes. I recalled that my father used to sing them in my childhood, but then he probably forgot them all.

Hesed 31 is very important. I like to socialize with people and Hesed offers very interesting subjects for discussions and I like to be there. For the first time in my life I identified myself as a Jew. I haven’t become religious, of course, and I never will, but Jewish history and traditions are very interesting and I enjoy learning them. It is wonderful that they provide assistance to poor people. They provide medications and food and take care of us.

However, there is a lot of jealousy around. Jews help and support each other while Ukrainians don’t have this support, although there are big communities in America and Canada and they can provide their assistance, but they don’t for some reason.

I would probably travel to Israel, because I am interested in Israel. I’ve read many books about his country and my relatives live there. We correspond with them, only I am ill and I wouldn’t bear the climate, which is very much like in Africa, and I am even afraid of going there on a visit.