Mikhail Gauzner

Odessa

Ukraine

Interviewer: A. Beiderman

Date of interview: February 2003

Mikhail Gauzner lives in a beautiful house, built in the middle of the 19th century and famous in Odessa. The sculpture of two mythical Atlas with the globe - the main element of its decoration -became one of the symbols of the city. Mikhail's father, once the chief engineer of one of the city's biggest plants, was given the large apartment in this building. The plate with his is still affixed to the door. There are a lot of books in the apartment - a sign for a cultured family in the former USSR. The furniture is from the 1960s and rather old. Mikhail turned out to be a very friendly man. He is ready to speak about his past recalling small details about his parents, his daughter and himself. He knows much less about his ancestors. I also met Mikhail's wife Berta. She was glad to see me and brought coffee to the room.

My family background

Growing up in wartime

My school years

My wife Berta

Our daughter Elena

Glossary

My great-grandfather on my mother's side was named Haim-Shmul Kurland. He was born about 1860 in a Jewish settlement of present-day Vinnitsa region, the name of which I don't know. He owned a pharmacy in the settlement and was deeply respected both as a professional and as a very devout person. My great-grandfather had three children born in this settlement: one son, Naum, and two daughters, Boba and my grandmother Maria. My great- grandfather and his children moved to Odessa in the middle of the 1920s. Being a widower, he lived with the family of his daughter Boba. He was old and stopped working.

My great-grandfather was a religious person. I can't say whether he went to the synagogue, but at home he prayed, put on his tallit and tefillin. In 1941, when the Great Patriotic War 1 started, he flatly refused to leave Odessa. He was very old and said, 'One has to die at home'. We are unaware of the circumstances of his death. The neighbors said after the war that 'he vanished, like all of yours.' Naum, Boba and their families survived the Great Patriotic War in evacuation. After the war all of them returned to Odessa. Boba died in the 1950s. Naum worked until a very old age at a pharmacy and died in the 1960s. Naum's daughter, Zhenya, is my only relative who still lives in Odessa.

My grandmother on my mother's side, Maria Vainshtein, nee Kurland, was born in 1886. After getting married my grandmother moved to Tomashpol, in present-day Vinnitsa region. My grandfather, Moisey Vainshtein, was born in 1880 in Tomashpol. He was the manager of a sugar factory. The people who brought sugar beet to the plant and worked at the plant were mostly Russians and Ukrainians. They treated my grandfather with great respect and called him 'our Moshka'. The extent of his religiosity is completely unknown to me. Most likely, he observed all traditions and laws required of a Jew; as for me, religion seemed to be a certain moral pivot in his life.

In Tomashpol my grandfather's family lived in an allocated apartment at the works. My grandfather certainly wasn't a poor man. When gangs 2 entered the settlement during the Civil War 3 and started pogroms 4, the men took a stand in front of his apartment and said, 'Leave Moshka alone. Moshka is a good man, you must keep him out of it.' And really, neither him nor his family were ever disturbed although the regimes constantly changed in Tomashpol. My mother told me about this when I was a boy.

My grandparents had four children: Asya, Mark, Boris and my mother Riva. All of them were born in Tomashpol. They had a nurse, either a Polish or a Ukrainian woman. They affectionately called her Darunya. Darunya was part of the family. She and my grandmother brought up the children and ran the household. Theirs was a large, united family; children were raised austere, without over-indulgence. The girls started working as bookkeepers at the plant accounting department from their earliest years. I know that the boys didn't go to cheder.

My grandmother can't have been very religious because my mother didn't receive religious education. In the middle of the 1920s my grandfather was brought to Odessa to be examined by the doctors. He must have had cancer but the word wasn't uttered in those days; they just said: swelling or gastric inflammation. My grandfather died in 1924 at the age of 44, in Odessa. He was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Lyustdorfskaya Street. My widowed grandmother Maria was left with four children and with neither occupation nor any means of living. They moved to Odessa to some distant relatives. They didn't receive the promised support from their relatives and were in dire straits at first. As far as I remember, my grandmother Maria lived with the family of her older daughter Asya. I remember that my grandmother was a very beautiful, stately woman with curly, black hair and lively eyes. But these are just general, fragmentary impressions of a five- year-old boy. During the Great Patriotic War my grandmother evacuated to the town of Andizhan [3,500 km from Odessa, in Uzbekistan] with Aunt Asya's family. She died of typhus in evacuation in 1943, at the age of 57.

My mother's older sister, Asya, was born in 1908. Aunt Asya didn't receive any special education; she worked as a bookkeeper before the Great Patriotic War. She was married to Solomon Shevelyov. Solomon came from the family of Odessa 'bindyuzhnik' [Odessa slang for 'heavy truck driver']. He was one of the young Komsomol 5 members, who became party members afterwards and sincerely believed in communist ideals. He was a mechanical engineer. He had a one-year-old daughter from his first marriage, Rosa, whom my Aunt Asya, his second wife, raised. Rosa loved Asya dearly and respected her; she took her as her real mother even when she got to know that she actually wasn't.

During the Great Patriotic War Aunt Asya, her husband Solomon and Rosa evacuated to Andizhan. Solomon had severe rheumocarditis before the war and thus wasn't recruited to the army, although he longed to. My aunt was pregnant. After she gave birth to her son Victor in April 1942, Uncle Solomon went to the front in June. Uncle Solomon was a political instructor throughout the war, was severely wounded, and became a Great Patriotic War invalid of the 1st grade. He was seriously ill all his life after the war and underwent numerous operations. He walked with crutches with a special device to tighten the leg because it wouldn't bend. He was seriously ill, and his wife no longer worked because of this. Uncle Solomon died in the 1970s. Aunt Asya died in 1986. Her daughter Rosa went to Israel in 1990 where she still lives with her daughter and son-in-law, and three grandchildren. My aunt's son Victor graduated from the Faculty of Letters at the Roman-German Department of Odessa University, he is an English translator. Victor and his family left for the USA in 1989; he lives in Boston now.

My mother's brother Mark was born in 1912. Mark served his army term in the Pacific Ocean Navy. After the service he stayed in the city of Sovgavan in Khabarovsk region, at the Pacific Ocean seafront. He got married to a Russian girl and they had two children. Mark worked as a sales manager of a defense industry plant throughout the Great Patriotic War. He lived in Sovgavan until the end of his days. He died in 1970.

My mother's younger brother, Boris, was born in 1918. During the Great Patriotic War he was a Red Navy man. He started his service in the suburbs of Odessa, with the seafront artillery battalion. He was wounded and shell- shocked. After the war he was a worker, lived in Odessa, and married a Jewish woman. In 1989 they went to the USA, to New York, where he died in 1999. Boris' son Aleksandr lives in Brooklyn with his wife and son and is in the insurance business.

My mother, Riva Gauzner, nee Vainshtein, was born in Tomashpol in 1909. She didn't receive religious education. She studied at secondary school. From the age of 14 she earned her own small income by working at the accounting department of the sugar factory where her father was the manager. I know very little about her life in Tomashpol. I remember what my mother told me about her friend, Wanda, a Polish girl. My mother considered Wanda her closest friend until her marriage, although they didn't meet for years in a row, only corresponded. My mother also remembered two of her schoolmates. I remember them because one of them, Zaltsman, became the director of the Chelyabinsk tank plant, and the people's commissar of the tank industry during Stalin's regime. And the other one, Tolya Levin, was a gifted violinist, one of Professor Pyotr Stolyarskiy's pupils. [Editor's note: Pyotr Stolyarskiy was a violin teacher in Odessa and one of the founders of the Soviet Violin School.]

After my maternal grandfather's death and my family's moving to Odessa, my mother started working as a bookkeeper in order to help my grandmother. Later, she finished a bookkeeping course and became a bookkeeper. My mother dressed very modestly but was an extremely beautiful girl.

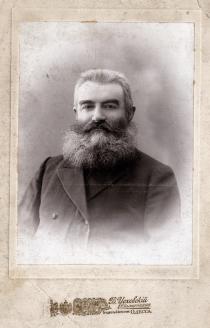

My great-grandfather on my father's side was named Josef Gauzner. He lived in Zvenigorodka, Podolsk province. In our family album are photos of my great-grandfather, taken in Odessa in the 1900s. There is also a photograph of my great-grandmother Gauzner, taken just at that time. It's a pity but I don't know her first and maiden name. Judging from the photos they must have been wealthy people. They are well dressed; my great-grandmother wears well-combed hair and jewelry. I guess that my great-grandfather somewhat helped in setting up my grandfather David Gauzner's dry goods store.

I remember my grandparents on my father's side very well. My grandfather David Gauzner was born in Zvenigorodka in 1881. Unfortunately I don't know where he studied. In our family archives there are still several postcards that my grandfather had written to my grandmother, 'To Mademoiselle Sofia Khasileva, Kalyus.' All of them are written in Russian, in smart handwriting, grammatically perfect, which indicates my grandfather's good education. How they got acquainted, I can't say, but such a loving pair as those two, who spent more than 50 years together, I've never seen. My grandparents got married in 1903. After the wedding my grandfather moved to Mogilyov-Podolsk where he owned a dry goods store.

Following the October Revolution of 1917 6 they eloped, so to speak, from being persecuted by the authorities for being bourgeois people. They moved to Odessa in the 1920s and settled down with some relatives. Grandfather David put an end to his business activities. Along with his best friend, an undergraduate smatter physician, he created some device to produce long- playing gramophone needles that didn't go blunt as quickly as conventional ones. My grandfather worked as a metal craftsman and found a market for those needles. The dirty part of his work was creating the device. When he came home his hands reeked of kerosene. He washed himself in the kitchen, snorting, and there was a huge pool of water around him. My grandfather had poor hearing, personal conversation was thus hampered, and perhaps because of this, or maybe, due to his trait of character, he was keen on books. He visited the city library once a week, on Friday, with an avoska [a Russian string bag, avoska literally means 'just in case']. And he brought the bag back, filled with books in Russian, and read. My grandfather only had two hobbies: his work and his books.

I only knew my great-grandparents on my father's side, Solomon Khasilev and great-grandmother Khasileva, from photographs taken in Odessa in 1903. Judging from the photos they are from the same society circle as my great- grandparents Gauzner were. They lived in Kalyus, Podolsk province. It was there where my grandmother Sofia Gauzner, nee Khasileva, was born in 1883. She had an older brother, Yakov Khasilev, who lived a very long life. He died in Odessa in 1953. Unfortunately I don't know what he did for a living.

My grandparents always lived with us. Grandmother Sofia was one of the most adored and beloved persons in the whole world for me. She was a housewife, but what a brilliant one! She was an exceptionally organized person, very strict, accurate and composed. I remember that she was magnificent in cooking sour sweetbread with red sauce; and the hamantashen she baked for Purim were simply delicious! She told me the story of Haman and Mordecai and what the meaning of hamantashen was. And the boy I was then, I bit off Haman's 'ear' and said, 'Now he gets what he deserves!'

As far as I remember, my grandparents didn't observe any Jewish traditions. It never occurred to me to ask if they prayed or believed in God. Outwardly nothing was manifested. At home they spoke Russian and changed to Yiddish when they wanted to hide something from me. Maybe they spoke to each other in Yiddish when they were in their room. I guess Yiddish was their native tongue when they were still children and lived with their parents. But once they became immersed into the life of such a civilized and international city as Odessa, they changed to Russian. There wasn't a single book in Yiddish at home, as far as I remember. My paternal grandparents went into evacuation with us, and returned home to Odessa after it was liberated. As far as I know, my grandparents had three children: Ezekiil, Tanya and my father Yakov.

My father's older brother Ezekiil was born in 1906 in Mogilyov-Podolsk. He was nicknamed Yuzya in the family. He was a laborer, and a very kind, unpretentious man. I remember how Uncle Yuzya used to dandle me on his lap and throw me up into the air. His relations with my father were normal, well-balanced. Uncle Yuzya got enlisted to the army in 1941 and perished at the front. I don't know if he had a family.

My grandparents had a younger daughter, Tanya, who was born in 1910. She died of either typhus or diphtheria when she was ten, before my grandfather's family moved to Odessa in the 1920s.

My father, Yakov Gauzner, was born in Mogilyov-Podolsk in 1907. He wrote in his biography that he had completed a secondary school; this must have been when he was still in Mogilyov-Podolsk. Then my father graduated from Odessa Machine-Building Technical School and started working as an engineer at some plant. Very soon he was recognized as an organizer, him being a born leader. While working at the plant he graduated from the evening department of Odessa Industrial Institute [today's Polytechnic Institute] as a mechanical engineer. Before the Great Patriotic War he worked as a mechanical shop superintendent at Odessa's well-known Kinap Plant [cinema equipment producing plant]. My father got acquainted with my mother around 1930, at some friend's party.

My parents were special for having no national prejudices when it came to choosing friends, and didn't have the habit of our people to create purely Jewish families. My father's milieu in Odessa, to use his words, was 'absolutely international'. One of my father's closest friends, Misha Ekelchik, was a Jew, and another one, Alyosha Maydanyuk, was Ukrainian. Alyosha, one of my father's co-students, became the instructor, and later the head of the industrial department of the Odessa regional party committee. He was arrested in 1937 and disappeared [during the Great Terror] 7.

I was born on 3rd June 1936 in Odessa, in the maternity hospital in Kulikovo Pole [city square near the railway station]. We lived on the third floor of a house in Lanzheronovskaya Street in the city center. It was a rather dark, dull apartment, but a large one. There were four rooms, a kitchen, and a restroom. Two rooms had windows; the other two were dark. Both my grandparents' bedroom and our room - I stayed with my parents - had windows with a look out over Lanzheronovskaya Street. The rooms were furnished with old furniture. I remember a huge dining table. There was also a cute little table on bentwood legs, with a marble table-top, on which I often hit myself.

I went to the kindergarten in Vorontsov Lane, not far from our home. My mother always worked very hard and couldn't stay with me all the time. She worked as a bookkeeper at the house-managing office. But in the hours she could spare for me, she was my dearest one. We never ever had pets in our house. My father suffered from a rare phobia: he was afraid of birds, of their wings clapping. He would suddenly become unreasonably terror- stricken. Wishing to play a trick on him once, some of his friends brought in a sea-gull. My father's eyes went white; he jumped onto the windowsill of an open window and said, 'If you don't take it away at once, I'll jump out of the window.' Our pre-war life was rather modest; I don't remember any noisy dinner parties, although my parents' relatives and friends visited us often.

When the Great Patriotic War started, the plant where my father worked was evacuated. However, my father was left behind with a group of workers, and they organized the production of mine housings at the machine shop, which was necessary for defending Odessa. About a month after the war began, in the middle of July 1941, Odessa started to be bombarded. There was a bomb shelter in the basement of our house. I remember how the older boys ran out into the streets after a night air raid to collect bomb fragments. I remember the bomb fragment with torn edges they gave me to play with. I remember how the mothers of those boys stormed out from the shelter and pulled them back in. When Odessa was bombarded excessively, and one of the bombs exploded somewhere nearby, in our street, my mother said, 'If it's our destiny, let us perish all together.' My mother and I moved into the little room beside my father's office at the plant and lived there until our evacuation.

My family, that is my father, my mother, me and my grandparents, was evacuated from Odessa, along with the last escapees, at the end of September or the beginning of October 1941. A huge departing crowd gathered in Tamozhennaya [Customs] Square, in front of the entrance to the port. I remember a blue sky, the bright sun, and the shriek of the siren - a raid commenced. The Germans threw bombs down onto the port, the ships, and when they ran out of bombs, they fired at the crowd in the square with machine- guns. There was horrible panic, people cried, wounded ones fell down. Uncle Boris, my mother's younger brother, who was seeing us off, took me into his arms and drew me inside some entrance. After the raid was over, Uncle Boris and I went looking for my parents and grandparents for a long time. The steamship we had to leave on, in order not to become a target for the bombers, hastened to lift its anchors and maneuvered to escape into the open sea. The steamship, it must have been named Lenin, exploded on a mine. Almost everybody on board perished. So, that German raid saved our lives. After a while my father got tickets for another vessel; it was named Kamenets-Podolsk. We settled in a hold where it was very stuffy, over- crowded, and there was no drinking water. 'Our' steamship was lucky to pass the mine fields, it escaped the air raids, and we finally arrived in Mariupol [Azov Sea port].

From Mariupol my family went by railroad in a heated boxcar to Yoshkar-Ola [1,600 km from Odessa]. The whole group of evacuated people was housed in the exhibition hall of the former Museum of Regional Studies, which, to me, a five-year-old boy, seemed simply enormous. About forty people lived there. Living space for individual families was partitioned off with sheets hanging down from ropes. Under these living conditions it was no surprise that I got membranous pneumonia. The illness was severe. There was actually no medicine, and the available treatment was insufficient. The doctors gave up their attempts to heal me.

My mother told me that the winter of 1941 was very severe. They told her that there was a local doctor, a very old and experienced one. If not him, no one would be able to save me. They gave her the address. With difficulty, late at night, she found a wooden house on the outskirts of the city. She knocked on the door. The doctor's wife opened the door and said that the doctor himself was ill and wouldn't see anybody. And she closed the door in front of my mother. In despair, my mother kneeled on the icy threshold and started praying. She couldn't explain to me afterwards who it was she was praying to, but still she prayed. After a while that woman opened the door again and said, 'Stand up.' An elderly doctor came out wrapped up in a woman's shawl, and went with my mother to see me. Somehow he managed to cure me. How exactly, I don't know...

We lived in a small flat in Yoshkar-Ola until 1944. I actually didn't see my father during that time. He was busy at the plant day and night. It was a fusion of the Leningrad Optical Engineering Works and Odessa Kinap Plant, which also produced optics. The plant manufactured tank ordnance gun sights. Like all the plants associated with the People's Commissariat of Armament it was supervised by the infamous Laurentiy Pavlovich Beriya 8. My father, who was present at the meetings in the director's office, told me that quite often he heard Beriya shouting, 'Where are the sights? Penal battalions - that's where you'll go!'[Editor's note: Penal battalions were subdivisions of the Soviet Army to which people were sent for punishment during the war. They were used at the most dangerous frontlines, basically sent to sure death.]

Soon my father was appointed superintendent of the engineering shop, which was under intensive construction. The work stopped neither at day nor at night. He came home from time to time, had a nap for several hours and returned to the plant. It was my father who made sure the work in this shop went ahead, and it was for that reason that he received the 'Order of the Red Banner of Labor' in 1943. I still have the issue of the Izvestiya newspaper, which published the names, patronymics, and family names of people awarded an order. Anti-Semites would be horrified: there are so many Jewish names, patronymics, and family names; about half of them, I'd say.

My father joined the Communist Party by the end of 1943, after the victory of the Soviet Army at Stalingrad. Afterwards he told me: 'Before the war I never shared the communist ideals, I was a non-party engineer. But during the war I understood that the Party was that very force, the only one that could organize resistance to Hitler, and bring victory.' This was at a time when he couldn't imagine himself not being in the Party any more. He often told me that during the Great Patriotic War, as an official person, he never confronted any anti-Semitism directed against him.

In 1944 we moved to Sverdlovsk [2,300 km from Odessa], where my father was appointed chief engineer at one of the hugest optical-mechanical device plants within the People's Commissariat of Armament. The plant manufactured aerial cameras, devices to obtain intelligence data from air as well as objective data on the bombarding and attacking results. It's difficult for me to judge what and how much my father did, but there's this one episode I can tell you about.

General Headquarters issued an order: for a specified number of enemy planes brought down, and tanks bombed, a pilot received the title of 'Hero of the Soviet Union', for such and such a number - 'Order of Lenin', for such and such a number - Order of the Red Banner of Battle, and so forth. It was stipulated that the results of bombing could solely be proven by the aerial photographs. The cameras were obsolete, so the pilots had to go further down to get sharp photos. The plane losses immediately increased.

The marshal of aviation, Vershinin, the head of the Air Force, issued an order by which he absolutely prohibited to go down under a specified level. Once photos were brought to him, which clearly depicted the result of the bombing. Instead of awarding the pilot, he ordered to reduce him to the ranks. He assumed that it was due to the fact that the pilot was flying too low, that the photos were so accurate. However, he was told that the pilot had not violated his order and that those photos were shot with cameras from the prototype batch of the Sverdlovsk plant, at the height designated by the rules. The marshal requested the inference of the Air Force Research and Development Institute. They confirmed. After that Vershinin ordered to recommend the plant workers for governmental awards. My father received the 'First Degree Order of the Great Patriotic War'. This award was only assigned to fighting officers partaking in battles.

My first recollections of Sverdlovsk are connected with temperatures of minus 40(C. It was Artillery Day, and we went to the main square to watch the salute. My nose was frost-bitten. Our first apartment in Sverdlovsk was in an old, wooden two-storied building with squeaking floor boards. It had two rooms. There was a toilet inside the apartment, but it wasn't a water- closet. The laundry was dried in the yard, but because of the severe weather conditions it froze, kind of turned to stone.

My grandfather David worked at the same plant as my father. He wasn't a locksmith any more; he was a warehouse executive. My grandmother and mother didn't work. In 1947 my father received a large three-bedroom apartment with all comforts in a newly-built house. One room was for my grandparents and one for my parents. I slept in the living room.

I started school in Sverdlovsk in 1944. I could already read fluently in Russian and was rather good in writing, but only in print letters. I had taught myself. I studied in the 1st grade for about a month and then I was transferred to the 2nd grade. I finished primary school in 1946. From 1946 to 1949 my closest friend was Dodik Kopilevich, a Jewish boy with brilliant talents, of subtle intellect. Simply, a superb, smart boy. Dodik's family was very needy; his father had gone to the front and perished. His mother was left alone with three small children. My father was chief engineer at the plant, and we had no problems with food. My mother tried to pep up Dodik, but he was a proud boy and on various pretexts tried to escape her attempts. We prepared for lessons, skied and went to the cinema together.

I never saw Dodik again after we left Sverdlovsk in 1949. Then, in 1964, many years later, I was returning from work in Odessa, it was pouring with rain and I noticed a soaked figure wandering across the yard, water dripping from his hat. It was twilight already. He addressed me with the words, 'Don't you remember by any chance ...' and stopped. I said, 'You're looking for somebody?' And he answered, 'For you.' The man turned out to be Dodik. He graduated from Sverdlovsk Polytechnic Institute, became an atomic fuel expert and worked in the closed Chelyabinsk-40 settlement. [Secret town, called only by its postal code, one of three major facilities east of the Ural, which produced material for Soviet nuclear weapons.] He had pursued a career up to the position of superintendent at a huge shop, so on the materialistic side of things everything was okay with him, but he wasn't allowed to go abroad.

Other than that, I remember the afternoon of New Year's 1948. My friend and classmate Igor and me went skiing across the railway embankment into the nearby forest to get a fir-tree, armed with a kitchen knife and a rope. We hadn't told our parents. We got lost in that forest and wandered around in the snow until twilight. Then somebody crossed our path and helped us to find our way out of the forest. Well, we did manage to cut a fir-tree with a blunt knife and dragged it back home on our shoulders. It was a quarter to twelve. When we finally fell into the room, covered in snow, my father was pacing up and down the room, and my mother was in despair. It was one of those rare occasions when my father left the plant early in order to celebrate the New Year. We were only saved from being scolded because my parents still wished to celebrate the New Year and were hurrying to a party.

From 1947 on, my father started to send his applications to the Minister of Armament, Mr. Ustinov, for being transferred to Odessa, to get his former post. It took long until he let him go. It wasn't until 1949 that he managed to transfer to Odessa Kinap Plant as a chief engineer. The head of the central administration, Mr. Polonskiy, helped my father. After we moved to Odessa they gave my father the apartment in which I still live now. I, my grandparents and my mother followed my father soon after his departure. My first impressions were from the winding - as I named them - trees in the square around the Opera House, with the knotty, bent trunks and the bright azure colored sea. I had a feeling that I had arrived home. It must have been stimulated by the fact that my parents always spoke about Odessa with such aspiration, with such caress. There weren't that many ruins any more in 1949. In the five years that had passed since the liberation of Odessa many houses had been restored. There were ruins behind our house, where I would run to and play with the boys after classes.

It was in Odessa where my father encountered anti-Semitism for the first time, when he came to the regional party committee and introduced himself to the head of the industrial department. The latter said, 'We didn't invite you here. We have our national cadres.' My father was in a fury, hurried to the plant, called Moscow, Mr. Polonskiy, the head of the central administration. A day or two later, my father was invited to the secretary of the regional party committee, who apologized for his colleague. My father began to work. He usually arrived home at ten at night, sometimes at eleven. He was hardly ever at home on holidays.

By the end of 1951 a commission from the State Control Ministry arrived at the plant. There was such a ministry during Stalin's regime, headed by Mekhlis, a Jew by the way. He was appointed one of Stalin's 'watchdogs'. Stalin empowered him to interfere with the work of any administration. All of a sudden, the director of the plant became 'ill', and my father met that commission and answered all their questions. As a result of this commission's work, my father was dismissed - groundless. He phoned Mr. Polonskiy in the central administration. The latter said that my father should not worry - justice would be restored. But when my father came to Moscow, he found out in Mr. Polonskiy's reception-room that a co-worker, who was also a Jew, had been dismissed, too. My father couldn't find a job anywhere.

It was the end of 1951 - the campaign against 'cosmopolitans' 9 was in full swing. My father was well acquainted with the directors and chief engineers of most of Odessa's machine-building plants. Some of these executives wouldn't accept him on various pretexts. Others would pat him on the shoulder but say that they couldn't employ him. Some of them would turn away when they met him in the street and wouldn't exchange greetings. In the beginning my father didn't understand that this behavior was connected with the anti-Semitic campaign. But when he got to know that the majority of Jews working as chief engineers or directors at Odessa plants had been dismissed, he realized that it was state anti-Semitism.

I remember another episode in connection with that period: We had a relative in Moscow, Lazar Schlaine. He had been a Komsomol member since 1920, and started off as a blacksmith's assistant in the forge shop of an automotive plant in Moscow. Later he became the superintendent of the blanking shops at the same plant. He was arrested in 1952, in the party bureau premises where he was summoned to on a party routine pretext. Lazar was exiled to the uranium mines, without a right to correspond and with no medical support. His family was deported from Moscow. He returned in 1953, soon after Stalin's death, an aged, tired man without a single tooth. When I was a student at Odessa Polytechnic Institute he was teaching me practical skills at the automotive plant. I remember him saying, 'Stalin was unduly informed. It makes no difference, the Party is right. Jump as you may, but the Party was okay'. I asked him, 'Uncle Lazar, how can that be?' And he answered, 'You don't understand. The communist idea is so superb that outlay is quite probable.' And, you know, he wasn't a narrow- minded man!

A few months after my father's dismissal the chief engineer of the Polygraphmash Plant, a Russian called Ivan Sinyavskiy, whom my father didn't know, called him up and offered him a job as the plant's chief manufacturing engineer. Surely, my father was happy. Later Ivan Sinyavskiy was transferred to the automated foodstuff processing machinery plant. He took my father with him to be the superintendent of the technical department, and afterwards the chief manufacturing engineer. My father worked there until his retirement.

In 1949, when we returned to Odessa, I entered the 7th grade of a school near my home. It was a boys' school then. I studied with great interest and was engrossed in Komsomol activities. I was also a leading character, just like my father. I could be youthfully irreconcilable, which I regretted later on. I was the Komsomol organizer of my class and a member of the school Komsomol committee. I organized all the cultural work. While in the 8th grade, I was recommended to the post of the school Komsomol leader. It was then that my Jewish friends said to me for the first time, 'Mikhail, don't you meddle with this. You won't be approved by the district committee.' And, at that point, I recalled my father's past experience. I had a feeling that anti-Semitism only existed in adult life and that we, youngsters, were spared of it. I wasn't elected, of course.

In those years I was on friendly terms with Mark Voloshin, a Jew, son of the very well-known surgeon in Odessa; Garik Divinskiy, also a Jew, and Garry Lorber, a Jew who got fascinated with religion and, after trying all known religions, dwelt upon Russian Orthodox Christianity. My other friends were: Felix Kogan, Yura Feldshtein and Mosya Vergilis, who had survived in the Odessa ghetto. I made friends with Russians, too: Oleg Malikov, Vitya Lutsenko and Alik Chaika. Among us one was valued for his human qualities and not for his nationality.

When Stalin died on 5th March 1953, my grandfather David Gauzner, who could hardly be suspected of love for the Bolshevik party [the Communist Party], cried and said to me, 'Mikhail, what's there ahead? You see, everything may go topsy-turvy without the man. And we'll have it served right upon us.' He was afraid of sedition because they always beat the Jews in troubled times. My father's reaction was ambiguous. On the one hand, he had survived the period of the struggle against 'cosmopolitans' and had no illusions left as to the attitude of Stalin's regime towards Jews. On the other hand, he was a product of his age. My father had survived the war under the guidance of the most potent organizers, and considered Stalin a superb organizer and creator of that machinery. I was the Komsomol organizer of my class at the time, and we organized a guard of honor in front of Stalin's portrait with a black crape band. I watched particularly that nobody would stir things up because it would be committing sacrilege. Well, we were like that in those times.

I finished school with a golden medal in 1953. I dreamed of becoming a doctor. Yakov Voloshin, my friend Mark's father, more than once caught me in the act of looking through the medical books in his study, and, being aware of my dream, would talk me out of this and told me the great secret - the words of Ivan Deineka, the late rector of Odessa Medical Institute, 'I will have as many Jews at my institute as there are employed in the underground works in the mines of my native Donetsk. [Editor's note: Mining was not a typically Jewish profession in the USSR.] Mark also finished school with a golden medal and entered the Medical Institute. But Yakov Voloshin, the leading Odessa surgeon, had to go to be received by Deineka and ask humbly for his son.

Hence I decided to follow into my father's footsteps and entered Odessa Polytechnic Institute - without exams because I had a golden medal. Many of my Jewish friends could enter Odessa Polytechnic Institute - anti-Semitism wasn't as severe there, although it was 1953, the time of the Doctors' Plot 10. As far as I remember, the doctors were released in June, and we were admitted in August. The institute was relatively liberal, mostly due to its rector, Victor Dobrovolskiy. Studies were very easy for me. I was greatly attracted by the public activities. I was a member of the Komsomol bureau of my year, later of the department and finally of the institute. In my undergraduate years I was elected to the Komsomol committee bureau of the institute and was responsible for organizing activities. I also led the Komsomol meetings. By the way: the identical head of organizational activities at Odessa Medical Institute was my closest, now late friend Victor Leshchivker. He was also a Jew, and later became a splendid surgeon in Odessa, and assistant-professor at Odessa Medical Institute. When I was in my senior year, the party organizer of the institute told me to write an application to the Party and promised his recommendations. I answered that didn't consider myself apt. It was a lame excuse - I just didn't want to join the Communist Party.

In 1958, after graduating from the institute, I went to work at the design office of the radial drilling machine-tools plant and found myself in excellent fellowship, headed by a Jew called Boris Bromberg - the leading designer, whom I consider my No. 1 teacher. He was a brilliant engineer, an erudite and very interesting person. Our curator was deputy chief designer Mikhail Nadol, also a Jew. The chief designer was a Jew called Fridrich Kopelev, a very well-known person in the machine-tool industry. The greater part of my accomplishments is due to science I studied under the guidance of my teachers. I wasn't a born engineer, but I always found interest in what I did. I would walk to work, murmuring songs. I jumped out of bed, sat at the desk and started drawing something with haste. The answer to a problem would come to me in my sleep. It meant that my brain worked non- stop. I liked work, I found it very interesting. When I was working for my second or third year, the secretary of our department party bureau invited me and suggested that I wrote an application to the Party. My answer was the same, 'I consider myself unapt.'

I got acquainted with my future wife, Berta Kelshtein, in 1961 when I was 25, and she was 22. We got introduced to each other by a mutual friend. It was a brief encounter in the street that resulted in nothing. A year later, I spent time with this same friend and came back from a tourist walking tour. Following habits, our tourist company went to the seafront Zhemchuzhina Restaurant in Arkadia in the evening. I met Berta again there. [Editor's note: Arkadia is a well-known Odessa beach, a recreation place.] We stayed late into the night and danced. Night. Moonlight across the sea. I walked her home; it was three in the morning. Deep inside I knew for sure - I was in love. Three months later, on 5th August 1962, we got married.

My wife was born in Zhytomyr in 1939. Berta finished school with a golden medal and entered the Department of Mathematics at Odessa Pedagogical Institute. In 1962 she graduated and worked for a year at the Molodaya Gvardiya [Young Guard] Republican pioneer camp. Later she was employed by the most popular physical-mathematical school. She looked young for her age and was very beautiful. When she peeped into the classroom the pupils thought she was a freshman. But she never had problems with discipline: her pupils always loved and obeyed her.

Berta's father, Haim Kelshtein, and her mother, Mirrah Schuper, were in the same year at Odessa Medical Institute, graduated in 1938 and got designations to Zhytomyr. He was a surgeon; she a therapist. Soon her father was appointed head of the city's public health department. In 1939, when Bessarabia 11 became part of the USSR, he was appointed head of the public health department of the Dniester River basin region. The family moved to Bendery. When the war started, he volunteered for the front although he didn't need to because he was a cardiac invalid. He perished at the front in August 1941, in the suburbs of Voznesensk. He wasn't far from the vanguard position operating on a wounded one when an air raid by German planes started. He ordered the physicians, who assisted him, to hide in the shelter. When they returned they saw that the wounded one was alive, but that the surgeon was lying there, dead.

The details of his life's end only became known to Berta's mother after the war. She was traced by her husband's colleague, who told her about it. Berta and her mother were evacuated to Volga River region, to Starotimoshkino in Syzran district, Ulyanovsk region. Her mother worked as a doctor. After Odessa was liberated, they returned to the city. In 1947 Mirrah got married for the second time, to Yakov Geiler, a construction engineer. Their son Mikhail was born in 1949. It's very hard for all of us to speak about him. Mikhail was a brilliant mathematician. He died in a car accident at the age of 23. Yakov Geiler treated his adopted daughter superbly; he was an exceptionally kind and very caring person. When he became aware of the fact that we were going to get married, he gave Berta a savings book with money he had put aside for her over the years.

After the wedding we settled down with my parents and my grandmother; my grandfather had died in 1960. Both my parents and Grandmother Sofia accepted Berta with all kindness. The whole family used to gather in our apartment, any pretext was good enough, be it Soviet holidays, or family holidays connected with special dates, or whatever. Family holidays were always very welcome and celebrated very cordially; we anticipated them because it was a very pleasant pastime for everyone.

I vividly remember my grandmother's last birthday. It was on 25th April 1965; she turned 82. She actually had no friends of the same age left. We reminded all our relatives not to forget to come to us on that day. Everyone gathered in the sitting room, around the table, laid by my mother and Berta, everybody was waiting for grandmother. And then, the door of her room opened and she came out. I still see her before me now, wearing a black polka-dotted dress with a white turn-down collar; her regal appearance, her hair tightly knotted at the back of her head. A queen came out! She sat down at the head of the table, smiled and joked. She was toasted to, she listened attentively, reacted lively, and then she asked me to pour her beloved vermouth into her liqueur-glass, smiled and said, 'My dearest, I'm very grateful that all of you came to congratulate me, I'm very pleased. It's especially precious because it is for the last time.' There was a sudden silence. I told her, 'What are you talking about, Granny?' She said, 'Mikhail, my mother died at 83. My sister died at 83. My brother died at 83. We, the Khasilevs, live until we are 83.' She died in late September 1965. She was only confined to bed for a month before her death.

Half a year later, in 1966, a daughter was born to Berta and me - our only child, Elena, the light of our life. Everyone in the family, that is my parents, my wife's parents, and me and my wife, dearly loved her. When Elena was still small, my longtime friend, Garry Lorber, came to our home and asked permission to look at her. He stood over the cradle for a long time and then he uttered, 'Mikhail, what a complicated life this girl will have. But afterwards it will be okay.'

To our regret, Elena's childhood really wasn't a cloudless one. When she was in the 2nd grade scoliosis in the third stage was diagnosed. All our attempts to organize the necessary medical treatment remained unsuccessful. I was advised to take her to Moscow, to the Moscow Traumatology and Orthopedy Institute where I got to know Israil Kohn, a Jew. He was the leading specialist in the conservative treatment of scoliosis in the Soviet Union. I took Elena to him for treatment twice a year. Sometimes she stayed in Moscow at our friends' for a month. She also underwent treatment in the Crimea twice, for half a year each time. I still worship the people who worked there. With what care they treated the children, how they pitied them, and how they tried to brighten up their lives! I could tell tales without end. Elena wore a corset and slept in a plaster bed to which I bandaged her so tightly that there were red spots all over her back in the morning. Elena's whole life was scheduled according to the treatment. I played the role of a 'severe dictator', prohibited everything that could interfere with the treatment. Owing to the qualified treatment and all our efforts, Elena had fully recovered by the end of the school year.

Despite Elena's illness, we spent every summer, with the exception of two years when my daughter was at the spa, traveling around by car. I constructed a rigid bed for her on the back seat of our car, which we bought in 1971. We traveled across Ukraine, the Baltic states, Belarus, around Moscow, the Caucasus and the Crimea. We traveled all over the European part of the USSR. These travels were a delight to all of us, but Elena was particularly happy about them. You see, in her childhood she knew neither how to play in the yard, nor how to ride a bicycle, nor school parties, nor dancing. She always read a lot and had a good knowledge of Russian and foreign literature. We always subscribed to several literature- and-art magazines and exchanged opinions on the latest literary novelties. We tried not to miss guest performances by the metropolitan theatres that visited Odessa every summer from the 1960s to the 1970s.

I became the leading designer of the radial drilling machine-tools plant in 1962 and held the position until 1980. In my active life as a designer- constructor I often had to go with a mission either to achieve agreement over our designs or to set up the machine-tools manufactured at our plant in companies. These included Kamsk automobile works, and some large Moscow plants, Kostroma, Kazan and Yaroslavl. And I could continue enumerating: I have about two dozen patent certificates. Our body of authors has seven patents in the leading capitalist countries: USA, Japan, France and Germany. I have some publications in scientific magazines, but I never occupied myself with science as such.

In late 1985, when I was returning home in the evening, I fainted while driving the car. When I came to myself, the car was standing close to the kerb, the motor was running, and my head was on the steering wheel. Somehow I managed to get home and drive the car into the garage, but I couldn't close the garage door any longer. I was brought to hospital; it was an infarct. When I was allowed to work again my doctor, a Jew, told me, 'Please consider that you need less strenuous, less nerve-racking work. We'll write you a letter stating that you need to be transferred to a more quiet position.' I was compelled to change from the active constructing design to the customers' service. Just then, in 1986, my father died, and three years later my mother passed away. They were buried in the Jewish cemetery in Slobodka 12, but not in accordance with Jewish traditions.

My daughter Elena always showed interest in her origin, just like any curious child, but in terms of genealogy, not nationality. I first explained nationality issues to her when she was in the 8th or 9th grade and we started to discuss her future profession. She longed to be a doctor. To this I objected that she would never become a doctor because it was almost impossible for a Jew to enter Odessa Medical Institute. She was silent for a long time because she had never encountered anti-Semitism in her life before. Then she said, 'Daddy, if I can't be a doctor, it's all the same to me, what I will be'. I started taking her with me to the plant to get her acquainted with my profession.

When Elena finished school with a golden medal, we sent her application to the electro-technical department of Odessa Polytechnic Institute. The papers only stayed there a fortnight. Once, in the middle of July, when I returned from work Elena declared to me and my wife that she had withdrawn the papers from Odessa Polytechnic Institute and submitted them to Odessa Medical Institute. I used the last argument I had left and asked, 'Elena, what will you tell your schoolmates if you aren't admitted to the institute?' She got indignant and replied, 'Why should I not be admitted, I will enter, and if not, my friends will know the reason!' Well, there was little I could add; I didn't have any arguments left.

The first exam was physics. She was being put out mercilessly. She was just beginning to answer, and they said, 'Miss, you are not answering the question.' She was taken aback and said, 'How can that be? I just answered this very question.' 'You are so sure. Well, proceed.' She spoke some more words, and was interrupted, 'Miss, why did you start there? Is it correct to start there?' She said, 'Tell me what I have to start with, and I'll start with exactly that.' And when the examiners told her the next time, 'You are wrong', my daughter answered, 'You feel I'm wrong? Have you got a red pencil? Mark the spot in my synopsis please, and write 'wrong'. They said, 'What for?', and her reply was, 'I hope my draft won't be destroyed and I will appeal to the selection committee. I'm sure this is right.' Elena left the physics exam with a white face and blue lips but with a 'four' mark - she had succeeded over the preconceived opinion of the examiners. All her exams were like that. In the end she entered the therapeutic department. She was a magnificent student, and throughout the six years of her studies she never once experienced any bad treatment due to anti-Semitism.

Elena married a Russian man called Alyosha Kobelev in 1986. He also graduated from Odessa Medical Institute and is a neuropathologist. Their son Pavel was born in 1987. After her graduation in 1988 Elena started working at Odessa Cardiology Center. In the late 1990s she was assigned to the highest doctor's category. Today she is the leading doctor of the Cardiology Center. Our grandson Pavel is a 9th grade pupil of the Second National Ukrainian Grammar School where my wife holds the chair of natural and mathematical sciences. She has a Soros' 13 teacher diploma. The diploma is awarded according to the mathematics students' questionnaire results. Besides, Berta has received George Soros grants twice.

My wife and I visited Israel in 1997. I understood that it was a completely unique place, I don't know if there's another one like it on earth. It has a very special flair, especially Jerusalem. We were in Jerusalem twice, but only on flying visits because we stayed in Holon with a friend of mine who had invited us. We traveled all over Israel with my friends and relatives. I heard from them that every bush and every tree in that country had been planted by human hand. And there I felt that I was one with that heroic people, that I belonged to the Jewish people. I have to admit that I wasn't overcome by religious inspiration, it was rather the spirit of these heroic, proud people that managed to create their own state and restore national independence.

I'm afraid but I didn't notice any special way of Jewish life being revived in our city, Jewish cultural and Jewish community life included. I've always been very distant to all this. The theme wasn't among my interests. But I've never been an antagonist so far. When I was still at work, although I had already been a pensioner for several years, all my Jewish colleagues advised me to enlist to the Gemilut Hesed charity center. To that I answered that I wasn't a pauper. I still worked and as little as we were paid, I didn't feel I had a right for charity. I have hearing difficulties, and they started tempting me, 'They give you a perfect, imported hearing apparatus. They give you perfect English eyeglasses.' I still wouldn't conform.

In 2000 I quit work because of my serious illness: lung cancer was diagnosed and they suggested that one lung should be removed. My daughter said, 'It will never happen until we are a hundred percent sure.' She and her husband took me to the oncology center in Kiev twice. Elena came up with a probable diagnosis, an alternate one. And she proved to be right - it was tuberculosis. I was congratulated on this... And that was when I did turn to Gemilut Hesed because the treatment was prolonged and expensive. I'm indebted to them for the help they rendered.