Masha Zakh

Tallinn

Estonia

Interviewer: Ella Levitskaya

Date of interview: March 2006

I conducted this interview with Masha Zakh in the Jewish community in Tallinn 1. Masha was willing to tell me about her family and her life story, though she warned me there was hardly anything quite thrilling there was to hear about whatever events in her life, but still she wanted this interview to be in the memory of her deceased father, of whom she has dim memories, and the family of her husband, who had passed away before time. Life did not pamper Masha, but she has never given up or lost her sense of humor. Masha is a plump lady of average height. One can tell she was quite pretty, when she was young. Her gray wavy hair is cut short. Masha is sociable and friendly. She lives with her daughter's family. Her mother-in- law helped her to raise her daughter at her time, and now Masha is raising her grandson.

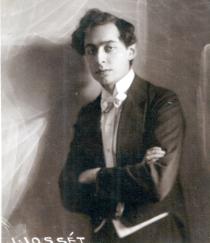

My paternal grandfather and grandmother came from Tallinn. My grandfather's name was Meishe Stumer and my grandmother was Hane-Rokhe. I don't know when they were born. I don't know what my grandfather did for a living. My grandmother was a housewife like all married Jewish women at the time. They had three children. My father, Solomon Stuper, was the oldest. He was born in 1905. My father's brother Zemakh was born in 1907, and his sister Bertha was born in 1909. As far as I know from what my mother told me, my father's parents were quite wealthy. My father studied in a general education Jewish school. His brother Zemakh and his sister Bertha studied in a Jewish gymnasium in Tallinn 2.

My father's family spoke Yiddish at home. All of them could speak fluent Estonian and Russian. Estonia belonged to the Russian Empire at the time. Russian was the official language, but all residents in Estonia spoke Estonian in everyday life. Russian was common in the areas near the Russian border. In Tallinn most residents spoke Estonian and German.

My father's parents were religious. They observed all Jewish traditions celebrating Sabbath and Jewish holidays at home. They went to the synagogue on holidays and celebrated Sabbath at home. My grandmother followed the kashrut. It goes without saying that she had special Pesach crockery. She kept it in a specific cupboard, and the family used it once a year on Pesach. As for everyday use, we had two sets of crockery: for meat and dairy products each. There were kosher stores and a shochet, a kosher slaughterer, in Tallinn. There was also a large choral synagogue 3. Doctor Aba Gomer 4 was the rabbi. Daddy told me he was an intelligent, kind and educated man. Gurevich was a chazzan in the synagogue. People arrived from remote areas to listen to his singing.

There was a large Jewish community in Tallinn. Estonians had a good attitude towards Jews. There were Jewish pogroms all across Russia during the tsarist rule, but they never happened in Estonia. After the war of liberation 5, when Estonia gained independence and became an Estonian Republic 6, the attitude of Estonians grew worse. Jews had equal rights with Estonian citizens, except that they were not entitled to having officers' ranks in the army. However, they could choose any career or trade. There was no Jewish quota of admission to universities 7, which was applicable everywhere else in the Russian Empire, including Latvia and Lithuania. Young Jewish people from all over Russia studied at Tartu University. In 1926 cultural autonomy 8 was granted to Jews in Estonia. This strengthened the Jewish community in Estonia.

My mother's family lived in Põlsamaa [about 250 km east of Tallinn], a small town in Estonia. My mother's father was born in Estonia, though I don't know the town he was born in. His name was Meishe-Ele Zitron. My grandmother Rachel Zitron, nee Eizmann, was born in Põlsamaa in June 1886. My grandfather was my grandmother's second husband. Her first husband, Mr. Strazh, died shortly after they were married and they had no children. This is all I know about my grandmother's first marriage.

My grandmother had five sisters: Anna, Reize, Rebecca, Fanny and Bertha. Anna, whose family name was Feitelson, moved to Saint Petersburg with her husband. After the revolution of 1917 9 the Soviet rule was established in Russia, and there was no way for them to move back to Estonia. Anna came to Tallinn after the war. Her husband and son died during the siege of Leningrad 10, but Anna survived. She never remarried. Grandmother's other sisters lived in Estonia. They gradually moved to Tallinn. Reize's family name was Maizel. She had two sons and two daughters. Rebecca, whose family name was Danzig, had two children: son Abram and daughter Dina. Fanny had a son. Bertha married Iekusiel Naimark, a Polish Jew. He moved to Estonia from Kodin, a town in the vicinity of Warsaw. She had five children: daughters Zelda, Miriam, Roche and Alte-Dina, and son Zelek-Mikhl. All of my grandmother's sisters were housewives.

My grandfather earned his living, and my grandmother took care of the household. They had two children. My mother Dina - her Jewish name Alte- Dina - was the older one. She was born in Põlsamaa on 31st December 1912. My mother's younger brother, whose name I don't know, was born in 1916. He died in a hospital in 1940. He was still very young. This is all I can tell about him. As far as I know there was just this one brother. My mother finished an elementary Jewish general education school. Her mother tongue was Yiddish. My mother's parents were religious. They observed Jewish traditions, celebrated Jewish holidays at home and went to the synagogue on holidays.

My grandfather died, when my mother was still a child. My grandmother, who had to take care of her two children, decided to leave Põlsamaa for Tallinn to be closer to her sisters. In Tallinn she rented an apartment from a building owner. My mother had to go to work, when she was still very young. She had to earn her living. Mama had no vocational training. She was employed as a worker at the socks and stockings shop, Punane Kojt haberdashery factory.

My father became a shoe leather supplier. He cut out shoe top leather delivering it to shoe makers. My father lived with my grandmother and his brother Zemakh. My father's younger sister Bertha married Efraim Goldman, and they lived by themselves. The families of my parents happened to rent an apartment in the same apartment building. My parents just met on the staircase in their building. My father told his family that he would only marry Dina Zitron, if he were to get married at all. So it happened. My parents got married in October 1935. They had a traditional Jewish wedding. After the wedding they rented a large two-room apartment with a spacious kitchen in the same apartment building. My father's sister Bertha and her husband also lived in this same building. In 1936 her daughter Fruma was born.

I was born in 1936. I was given the name of Masha after both my grandfathers. Both of them had the name of Meishe, and my name also started with M. After I was born, Mama had a maternity leave to take care of me, and when it was over, she resumed her work at the Punane Kojt factory. My mother liked going to work and communicating with people. She actually didn't have to go work. My father earned quite sufficient, but my mother wanted to be independent. Both grandmothers were helping to raise me.

We talked Yiddish at home. I pronounced my first words in Yiddish. I picked up Estonian later and since 1940 I've spoken Russian.

I can't say my parents were deeply religious, but they did observe Jewish traditions. We always celebrated Jewish holidays at home. On Pesach Mama always cooked traditional Jewish food. We celebrated all holidays according to the rules. On holidays my parents went to the synagogue. I cannot remember celebrating Sabbath at home, but my parents didn't go to the synagogue on this day. The older generation was obviously much more religious than their children. This was what they needed, while for their children this was merely a tribute to traditions.

In 1940 Estonia became a Soviet Republic 11. Nothing seemed to change for our family. We had no wealthy relatives, and our family was not persecuted. My father went to work as a shoe leather cutter at a shoe factory, and my mother continued working at the Punane Kojt factory. She was well-respected at work. I don't think there was any anti-Semitism before the war even during the Soviet rule in Estonia. At least, this is what my mother used to say.

On 22nd June 1941 the radio broadcast that Germany had attacked the Soviet Union. The war began 12. This happened at noon, and the war was already on-going in Belarus. They were bombing Kiev. A few days later my father was conscripted to the Soviet army 13. His brother Zemakh and Aunt Bertha's husband Efraim were drafted, too. We were still in Tallinn. We were scared. I remember everybody arguing about whether it was worth leaving Estonia for some remote areas in Russia. Both my grandmothers were saying that nothing bad was going to happen if we stayed at home. Estonians had always had good relationships with their German neighbors. However, my mother must have known more about fascism than my grandmother. She insisted that we went away. My mother was a resolute woman. She managed to convince the family to leave.

My mother, my grandmother Rachel and I packed whatever we thought we needed and went to the railway station. There were trains all over the tracks. As soon as a train was full of passengers, it departed. We managed to somehow squeeze into a train before it departed. My father's sister Bertha, her daughter Fruma and Grandmother Hane-Rokhe Stumer caught the next train. We didn't even know where we were going. What mattered was that we went as far away from the German army and the front line as possible. There were bombings on the way, but fortunately, our train wasn't damaged. This was a long trip. We arrived at Nizhniy Yar where Mama obtained a letter of assignment to Dolmatov, Kurgan region in Russia [about 1600 km north-east of Moscow]. This was where we spent our years in the evacuation. We lived in a house on Sovietskaya Street.

We rented a room. Initially there were six of us sharing this room: my father's sister Bertha, her daughter and Grandmother Hane-Rokhe joined us there. Mama and Bertha went to work. They had to work to be provided food cards 14. My cousin, my grandmothers and I received dependants' cards for 200 g bread ration per day each. The bread was heavy and under-baked. It also contained bran and straw. Our daily rate was one slice per day, while Mama and Bertha's rate was larger. They shared their bread with their children.

Our life in town was more difficult than in villages where they could grow vegetables on the land plots that were provided to them. Those, who lived in town, could only buy vegetables at a market or trade food for whatever valuables, but we still had insufficient food products. My cousin and I picked nettle in spring and summer, and my grandmother made soup with it. We were very poor and starved. It was a good thing that we managed to survive. Our landlords and even strangers were giving us assistance. This was a terrible time, but people were kinder trying to support the needy ones.

When we arrived in Russia, we couldn't speak any Russian. I knew few words and before long I picked up more Russian playing with our landlady's children. Gradually, everybody else learned it. My grandmother took me to the market with her. I helped her with interpreting before my grandmother picked up a sufficient vocabulary to be able to speak the language. Mama and Bertha learned from their Russian co-workers. In the evening we all listened to the news on the radio.

A year later Bertha found new accommodation in another street in the same neighborhood where she moved together with Fruma and Grandmother Hane- Rokhe. In late 1941 my mother was notified that my father was dead, and Bertha also received a notification about her husband Efraim's death. Both of them served on a Soviet battleship, which sank near the Hanko Peninsula, Finland. Mama didn't mention to me that my father had died. I heard about this after we returned home from the evacuation.

In 1943 my cousin Fruma and I went to the 1st grade in the local Russian school. Studying was a challenge for me. Perhaps, this was because Russian wasn't our native language. I don't know why, but I often received low grades for my efforts. My classmates and teachers treated me and other evacuated children well. They were sympathetic and helpful. I felt no stranger among my classmates. There was no anti-Semitism either.

In November 1944 we heard that Estonia had been liberated from the fascists. My mother, my grandmother and I were the first to leave for home. Aunt Bertha, Fruma and Grandmother arrived in Tallinn a couple of months later. We had no problems with going back home. We were forced to leave our home and had the right to go back to our hometown. Our house was ruined by bombing. We stayed with our acquaintances. My mother went to the executive committee 15 where she received a two-room apartment on the 1st floor of a five-story apartment building. Initially it was stove-heated, and a few years later the municipal authorities provided for gas supply to the house.

Life was gradually improving. My mother went to work at the human resources department of a tram/trolleybus agency. I went to the 2nd grade in a Russian school. My grandmother did the housework at home.

In 1947 Mama married a local Jewish man. My stepfather's name was Haim Benjamin Kitt. He was born in Tallinn in 1909. This was his first marriage. He had not been conscripted to the army due to his health condition. He was in evacuation in the Ural with his parents. My stepfather had three sisters and three brothers. They survived the war and returned to Tallinn. My mother and stepfather were members of the Party. They didn't have a traditional Jewish wedding. They registered their marriage in a registry agency and had a wedding dinner at home.

My stepfather moved in with us. My mother and stepfather had their room, and I shared my room with my grandmother. I got along well with my stepfather. I remember being impolite with him one day. He told me to clean the floor and I replied that he wasn't my father to give me orders. However, this was the only time we had an argument. My stepfather was the director of a perfumery store.

We spoke two languages at home. My mother spoke Yiddish to my stepfather and grandmother. My Yiddish was rather poor, and so they spoke Estonian and Russian to me. However, I could understand Yiddish well, but my knowledge was insufficient to speak it.

When my grandmother was alive, we observed Jewish traditions. My grandmother did the cooking and did her best to follow the kosher rules. It was hardly possible to buy kosher meat after the war. It was hard to buy any food at that time. However, if there was meat at home, it was beef, veal or poultry. My grandmother didn't accept pork meat. She watched it that we ate dairy and meat products separately. We didn't even add sour cream to meat soup. We celebrated all Jewish holidays according to the rules.

For some time after the war matzah wasn't available in stores and my grandmother made it herself. I was there to assist her, since matzah has to be rolled during a 15-minute cycle to be appropriate. My grandmother used to roll the dough and I poked holes and put it into the oven. It was hard to cook all traditional Jewish food on holidays during the post-war years, but my grandmother did her best to manage. She made gefilte fish or chicken. She tried to make something delicious for holidays.

My stepfather also celebrated Jewish holidays with us after he moved in with us. On Yom Kippur we fasted as required for 24 hours. Well, my mother or stepfather didn't go to the synagogue, though. They were members of the Party, and if somebody had known they observed Jewish traditions, they would have had problems at work. The Soviet rule didn't appreciate religious people and fought against religion 16.

During the war the large choral synagogue in Tallinn burned down. Germans killed Aba Gomer, the rabbi of Tallinn. They tortured him before taking away his life. The town authorities didn't restore the synagogue after the war. The religious people were provided a small wooden house to accommodate a prayer house therein. There was actually no rabbi in Tallinn before the 2000s. There was no rabbi in the prayer house. There was a gabbai, an old man. He knew Jewish traditions, Hebrew and could read prayers. The gabbai could also conduct the services on Jewish holidays, wedding ceremonies and funerals. However, he had no special education. People just elected a knowledgeable man.

My grandmother always went to the prayer house on Jewish holidays. She was old and I accompanied her as far as the prayer house and met her after the service. I went there a few times with my grandmother, but I didn't know traditions and couldn't understand any prayers in Hebrew.

My grandmother always celebrated Sabbath at home. She cooked food for two days on Friday morning. We bought challot for Sabbath. In due time in the evening my grandmother lit candles and recited a prayer over them. Well, the rest of us, but my grandmother, had to go to work on Saturday. Saturday was a standard working day in the Soviet Union. It wasn't before the 1960s, when it became another weekend day, which was officially a day off. Previously there was a six-day week with only Sunday off. Mama and my stepfather went to work on Saturday and I had classes at school. My grandmother tried to do no work on Saturday. She spent her Saturday reading the Bible [Old Testament].

In 1949 my stepbrother Leo Kitt was born. When my mother and he returned home from the maternity home, he was circumcised. The elders from the prayer house were invited to our home. There was also a doctor to do the circumcision. Though we knew well all those we invited to my little brother's brit milah, the authorities somehow found out that we had this event at home. My mother and stepfather had to go to the militia office for an inquest regarding this subject. They also were questioned by the district party committee. I don't know what they explained at the police and at work, but there were no further consequences. I don't know, perhaps, there was some reprimand imposed on them as party members. However committed the authorities were to combat religion and traditions, most local Jews had their sons and grandsons circumcised. Whatever efforts the authorities undertook, this did not hinder people from observing Jewish traditions. They even had a chuppah at their weddings.

1948 was the time, when cosmopolitan cases 17 were prosecuted in the Soviet Union. This campaign was widely covered in the mass media. Since there were no cosmopolitans in Estonia, they fought wealthier farmers. They were called 'kulaks' 18, a common definition in the Soviet Union. In 1948 and 1949 resettlement 19 of large numbers of these farmers to Siberia was going on. The rest of them were forced to join the kolkhoz farms 20. Also, those resettled on 14th June 1941, and were back from exile, were subject to resettlement again. The police had their records, and they were arrested again and were subject to resettlement to Siberia. Large numbers of people were affected then. The survivors returned to Estonia in the late 1950s, when rehabilitation 21 began, but many had died in exile and the Gulag camps 22.

Of three men from our family that went to the front, only my father's brother Zemakh returned home. He served in the Estonian Corps 23, and took part in the liberation of Estonia from the fascists. Zemakh got married after the war. His wife's name was Anastasia. She was half-Russian and half-Estonian. She was a very nice person. After the war people didn't care much about mixed marriages. They loved each other well and lived in harmony. Their older daughter Ilona was born in 1946, and son Boris in 1950.

After returning from the front Zemakh went to work at the Prosecutor's office in Tallinn. Veterans of the war were well-respected then, and veterans of the Estonian Corps held high-level official posts in Estonia. However, Zemakh had to leave his office, when persecution of Jews in the form of fighting cosmopolitans and the Doctors' Plot 24 began. Actually, he didn't wait there until he might have any problems and left the Prosecutor's office for the Ministry of Road Transport. He worked there until retirement.

Zemakh's son Boris lives in Tallinn, and we keep in touch. Ilona lives in London, England. She visits Tallinn almost on a yearly basis, and we see each other. When she goes back, we talk on the phone sharing our news.

I studied at school until I finished the 8th grade. I had Russian, Estonian and Jewish classmates. There was no different treatment of any of us. I faced no anti-Semitism at school. I think, my Jewish classmates would say the same. Our teachers and classmates treated us well. We choose friends based on our interests. I did all right at school. I wasn't in the ranks of the best students, but I was no failure either.

I was a pioneer 25 and a Komsomol 26 member. I wouldn't say I was eager to join the pioneers or Komsomol. It's just that it was common that all students joined these organizations, and I did, too. However, I didn't care too much about this. I had older and younger classmates. The age difference was three or four years due to the war. My closest friends, Pesia Marienburg and Tsylia Perelman, were Jewish girls. They live in Tallinn now. I keep in touch with them. My other Jewish friend Lilia Malkina lives in Poland. We correspond and talk on the phone. I also had Russian friends. Many of them moved to different towns and countries. We see each other, when they visit Tallinn. We are old now, but when we get together, we feel like schoolgirls again. We recall the time, when we were schoolgirls and spent vacations in summer camps.

In March 1953 Stalin died. We heard that he died at school. We had no classes on this day, and got together in the school conference room. The school principal held a speech, and everybody was crying. I cried, too. I wouldn't say I was grieving that much. I believed it was only natural when old people died. Besides, he was someone I didn't know personally, but tears must be as contagious as laughter. Everybody cried, and I did, too.

I left school after finishing the 8th grade. I believed it was time for me to go to work and support myself and my family. My friends Pesia and Tsylia also quit school. Pesia went to work as a shop assistant at the perfumery store where my stepfather, Benjamin Kitt, was the director. Tsylia went to work at a plant, and I went to work at the knitwear factory. My mother worked at the HR department at the factory. I was a worker in the knitting room. I was a winder machine apprentice. When my training was over, I started working there.

I also went to the 9th grade in the evening school for young working people. However, I quit this school after finishing the 9th grade. It was difficult to attend classes after work. Besides, I was young and wanted to have some free time for myself. Some time later our factory merged with the Marat knitwear factory. They had three-shift work cycle, which was substituted by a two-shift cycle and finally by a single-shift cycle. I was a quality assurance crew leader. I worked at the Marat factory till I retired.

In 1959 my grandmother Rachel died. She was a strong woman and had no diseases. She died in a tragic accident. My grandmother was cooking and didn't notice, when her apron caught fire. Before my grandmother could reach the bathroom to extinguish the fire, she was on fire all over. She had many burns all over her body. She was taken to hospital right away. She lived three days before she died from the burns. My grandmother was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Tallinn.

My grandmother Hane-Rokhe Stumer died in the early 1960s. My uncle Zemakh installed a monument on her grave. Besides my grandmother's name, he had my father's name inscribed on it. My father had no grave, and this gave us at least an opportunity to come to our Jewish cemetery and recite a prayer in the memory of my father.

I met my future husband, Lev Zakh, at work. He was a mechanic at our factory. Lev liked me and asked me to date him. I liked him, too. We kept seeing each other. I was in no hurry to get married. We got married in 1960. We had a common wedding. We registered our marriage, and our mothers made a wedding dinner. After the wedding I moved in with my husband.

Lev's family came from Tartu [Estonia, about 180 km from Tallinn] where both his father, Itzhak Zakh, and his mother, Ida Zakh, were born. Ida was born in 1898. As for Itzhak, I can't remember, when he was born. Both families were quite wealthy. Itzhak finished a German gymnasium. Ida also studied in a gymnasium, but I can't remember any details. Itzhak took up some training related to jewelry business. He became a skilled jeweler and could make whatever fine pieces of jewelry. Itzhak's only brother Khirsh finished the Medical Department of Tartu University. He was a doctor. My mother-in-law Ida had a sister. I don't know how my in-laws met, but what I know is that finally both brothers married the sisters. Itzhak was doing well. He earned all right.

My husband Lev, the only son of Ida and Itzhak, was born in Tartu in 1929. Two years after he was born the family moved to Tallinn. Itzhak was the breadwinner, and Ida did the housekeeping. Itzhak had a little jewelry shop in the center of Tallinn. Itzhak had one employee working for him. He was also a skilled jeweler.

Lev went to the Jewish gymnasium in Tallinn, and Ida worked as a teacher in a Jewish kindergarten. Everything went well. Even when the Soviet rule was established, it didn't affect the Zakh family. The shop was appropriated by the Soviets, but Itzhak and his employee continued working in the shop. The resettlement didn't affect the family either. When the war began, the family evacuated.

As for Khirsh, Itzhak's brother, his life was harder. His daughter Sima married a young Jew from a wealthy family. His father owned a small jewelry store on Viru Street in Tallinn. In 1940 Soviet authorities appropriated this store, and on 14th June 1941 the whole family had to forcefully depart to the town of Kirovsk in Siberia. Sima's four children were born in Siberia. Avi and Nafthole, the older brothers, were quite strong and healthy. After Nafthole Sima had a daughter. At the age of six months the girl fell very ill. There was no doctor in this village near Kirovsk where the family lived. It was winter. They wrapped the girl in a blanket to take her to a doctor in the town. The girl died on the way. This was a terrible blow for the family. A couple of years after her daughter died Sima gave birth to a boy. His name was Benjamin. So the family had three sons.

They finally returned home after 15 years in exile. This became possible in 1956, after Stalin died, and after the 20th Congress of the Party 27, when Khrushchev 28 allowed rehabilitation of those in exile. However, the family wasn't allowed to reside in Tallinn. They received an apartment on the outskirts of Tallinn. Sima went to work as a teacher in the kindergarten, and later she was promoted to the position of director of this kindergarten. Sima worked there till she retired. Her sons received proper education and had their own families. Avi, the oldest son, died of cancer. Sima is still alive and all right. I often talk with her on the phone, and we visit each other. Sima is 87, but she is hale and hearty, she has a bright mind and good memory.

There was another tragic accident in my mother-in-law's family. Her cousin Frieda, much younger than Ida, was a very beautiful woman. Frieda and her family lived in Tallinn before the war. When the war began, Frieda didn't want to leave her home. She was telling my mother-in-law that there was nothing bad about the Germans, and that they were not going to hurt Jews. Estonia had been under German rule at some time, and there was nothing terrible happening. They knew German well, and she believed things were going to be all right. She was saying they would wear yellow stars, if necessary. What else was there going to be? They had managed more or less during the Bolshevik 29 rule, and they would survive the Germans somehow. Therefore, Frieda stayed in Tallinn.

When the Germans occupied Tallinn, they started arresting and killing Jewish residents. Many Jews stayed in Estonia thinking like Frieda did. Frieda was arrested right on a street. German soldiers pushed her into a bus where they raped and shot her. Some acquaintances told my mother-in-law what had happened after she returned to Tallinn.

My husband's family was in evacuation in Barnaul [Siberia, over 3000 km from Moscow]. My husband went to school there. Itzhak and Ida worked in a shop. They were accommodated in the house of a Russian family that treated them well. My mother-in-law told me that no one ever commented on their Jewish identity. Vice versa, their surrounding was helpful and supporting. They returned to Tallinn in late 1944, when Estonia was liberated. Itzhak went back to his jewelry store, and Lev went to work as a mechanic at the knitwear factory. He also studied in an evening school where he finished the 10th grade. My mother-in-law was a housewife after the war.

My husband's parents were kind to me. My father-in-law died in 1960, shortly after my husband and I got married. He was buried according to the Jewish rules in the Jewish cemetery in Tallinn. We lived with my mother-in- law. My in-laws led a traditional Jewish way of living. My husband's parents were religious. My husband was not as deeply religious as his parents, but he also observed Jewish traditions. Even during the Soviet period my mother-in-law did her best to follow the kashrut. She only cooked Jewish food. We only ate beef and poultry. We never had any pork or sausage at home.

When my husband's family returned to Tallinn after the war, my husband's parents always went to the prayer house on Jewish holidays. The former prayer house was quite near our house, but later it was removed, and the prayer house moved to another premise on Magdalena Street. This was quite a distance from our house, but my in-laws went to the synagogue regardless. After my father-in-law died, my husband and I accompanied my mother-in-law there and after the service we saw to it that she got back home safely. I attended the prayer house with her a few times.

My mother-in-law was a great cook. On holidays she always made something special: gefilte fish, chicken broth and forshmak with herring. We always had matzah on Pesach. My husband and I bought bread anyway, while my mother- in-law only ate matzah on Pesach. Se also strictly observed the fast on Yom Kippur. On holidays our relatives got together at our home. Sometimes we visited them.

We didn't celebrate Soviet holidays at home. However, we celebrated them at work. This was a mandatory requirement. We were also bound to go to parades on 1st May and 7th November 30. Those, who missed the event received no bonuses.

My mother-in-law only spoke Yiddish at home. My husband knew Yiddish well to speak it with his mother. Ida also spoke Yiddish to me. I understood everything she was saying, and I replied in Yiddish mixing it with Estonian, if I lacked words to express myself. My husband and I only spoke Russian between ourselves and to our daughter.

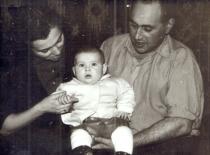

We had no children for quite a long time. Our only daughter Ilona was born in 1965. At that time maternity leave only lasted three months, and when it expired, I had to go back to work. My mother-in-law was there to take care of my daughter. When Ilona turned three, she went to a kindergarten. However, Ilona started getting ill very often, until finally my mother-in- law said she preferred to take care of a healthy child, rather than staying at home with a sick child. Ida actually raised our daughter, actually. She died, when my daughter was in the 9th grade.

Ilona was four years old, when my husband fell ill. He had headaches and was weak, but at first he ignored the symptoms. When doctors finally examined him, the diagnosis was frightful: he had malignant growth in his brain. It was too late to have a surgery, and neither the doctors nor we could relieve his suffering. In January 1970 Lev died. This happened a few months before he was to turn 41. We only lived ten years together. We buried my husband in the Jewish cemetery in Tallinn.

I stayed with my mother-in-law after my husband died. I couldn't go back to my mother. My stepbrother was there, and there was not much space in their apartment. Besides, my mother worked, and there was nobody at home to look after my daughter. Besides, my mother-in-law was very happy to have Ilona and me with her. She was very attached to her granddaughter, particularly considering that she was absolutely alone. Ida actually raised my daughter, and this was a great contribution on her behalf.

However, it was due to Ida that I never remarried. She told me that she didn't mind, if I decided to take care of my private life, but she wasn't going to have to put up with a stranger at her home. I understood my mother- in-law and had no bad feelings toward her. I know how terrible it must feel to outlive one's own son. So, we lived our life together. Ida died in 1982. Her grave is near her husband and son's graves in the Jewish cemetery.

When Soviet Jews were allowed to move to Israel for permanent residence in the 1970s, many of our relatives left. My father's cousin brothers and sisters, four of six brothers and sisters of my stepfather moved there. His two brothers died in Tallinn. My mother-in-law's family also moved to Israel and so did my father's cousin sister. I gave them whatever support I could, but I never considered departure myself for a number of reasons. I was at home here, and I felt uncertain about giving up everything, moving to another country and starting there from scratch. Had my husband been alive, we might have decided for moving to Israel, but I was afraid of going there with my young daughter and old mother-in-law. Besides, I'd lived my whole life in Tallinn and just could not imagine living elsewhere but in Estonia. The thing is, even visiting the Soviet Union from Israel was not allowed at the time. People were going there for good leaving their friends and relatives behind. That was nobody's fault. It's just that life changes and so do people. They have their own life and make new friends.

My daughter studied in a Russian general education school. She did well at school. She was a quiet and friendly girl. After finishing school, she entered the Light Industry College for the specialty of 'secretary and document control.' After finishing the college, my daughter came to work as a secretary. When Estonia gained independence 31, the factory was closed as an unprofitable enterprise. It took Ilona a few months before an acquaintance of hers started her own business and offered Ilona a job in her office. This is where Ilona works now.

Ilona married Anatoliy Avdeyev. Anatoliy is Russian, but I had no objections to their marrying each other. I only wanted Ilona to be happy with her husband. Anatoliy was born in Tallinn in 1956. His father served in the Navy and moved to Tallinn after the war. Anatoliy is the youngest of three sons. He works in a security company in the port in Tallinn. Anatoliy is a shift supervisor.

After the breakup of the Soviet Union, when Estonia gained independence, only the ones born in Estonia before 1940, or children of the victims of resettlement, regardless of their place of birth, were granted the Estonian citizenship. The ones who arrived in Estonia after its accession to the Soviet Union had to obtain the citizenship. Many people left the country, and the rest of them believe this to be rather unfair. However, they have to learn the language, pass their exams to obtain the citizenship, which they are rather reluctant to do. Anatoliy passed the exam and was granted the citizenship of Estonia. He's a bit shy to speak Estonian. He needs to work on his pronunciation. My grandson can speak fluent Estonian, and he often corrects his father.

My grandson was born in 1990. He was given the name of Lev after my husband. I was still working, when he was born. When he turned one, my daughter talked to me about my retirement in order to be my grandson's babysitter. I agreed and quit my job in 1991. We live together and share all household responsibilities.

Lev only spoke Russian before turning two. We spoke Russian at home. When my grandson started working with our neighbors' children, he made an Estonian friend. I was his interpreter for some time, but one day I said: 'Well, that's it. From now on you study the language and start speaking it.' And he did. We sent him to an Estonian school. At first we were thinking of sending him to a Jewish school, but we changed our mind. Teachers and students speak Russian in the Jewish school. Lev is going to live in Estonia. Therefore, he will need Estonian to continue his studies after school and to work thereupon. And so, we sent him to an Estonian school. He is in the 9th grade now. He is taller than me. Before the 8th grade he only had the highest grades in all subjects. Now he starts getting the 'good' ones. Lev has many friends at school. After classes they keep calling him asking, if he would go out. Unfortunately, Lev prefers the company of his computer. I don't think it's healthy to spend so much time at the computer. I tell my grandson to go see his friends, but I rarely succeed.

My stepbrother, Leo Kitt, was born with a heart disease, which became apparent, when he was a child. However, Leo never gave up. He finished an Estonian general education school in 1967. He still keeps in touch with his school friends. Leo then finished the Light Industry College. He worked as an engineer in a design office. When perestroika 32 began in the Soviet Union, and private entrepreneurship was allowed, Leo started his own construction business. He is doing all right. His business is not booming, but he is not starving either.

Leo married Rena, who was born in Tallinn. Rena's father is a Jew, and her mother is Estonian. Leo and Rena get along very well. They love each other dearly. They have two children. Their older son Robert was born in 1977, and Lenart, the younger one, was born in 1983. Robert was a very talented boy since childhood. He finished a general education school with a gold medal and entered Tartu University. When at school, he participated in various Olympiads and contests. He had numbers of medals and awards. Upon graduation, Robert became a post-graduate student. He defended his dissertation, and now he is thinking about the professorship. He's a smart guy.

Leo holds a very important position in a bank. He is a pension division manager. He often travels to Japan where they have an affiliate. Robert has two sons, one was born after another. Robert built a house for his family in the outskirts of Tallinn. It's a beautiful neighborhood, and the houses there are nice. The children just enjoy living there. Lenart, the other son, is a 3rd-year student at Tartu University. Five years ago Leo had a heart surgery. Everything went very well, and my brother says he has never felt better in his life.

My mother died in 1991. My stepfather lived two years longer. He died in 1993. They both lived a long life, and people treated them with respect. They were buried in the Jewish cemetery in Tallinn. All our relatives were buried there. The generation of my parents is gone, but also, all of our relatives of my age are gone. My father's sister Bertha died in the early 1970s. Her daughter Fruma married an Estonian man. He is a very nice person. In 1970 their son Edward was born. When he was three years old, Bertha took him for a walk. Edward fell and broke his arm. My aunt was so upset that she had a stroke. Poor thing, she was paralyzed for a long time before she died. My cousin Fruma also died of breast cancer in 1994.

Frankly speaking, when perestroika began in the Soviet Union, I had no high expectations in this regard. We were so used to whatever promises party leaders made never keeping them. I didn't think Gorbachev 33 was the man capable of turning the country in an opposite direction. One day Gorbachev visited the Marat factory during his trip to Estonia. He seemed too gentle and irresolute to me. He was joking and laughing. This was not the way Soviet leaders presented themselves. However, in the course of time I started noticing changes in our life. Actually, I've never been interested in politics. All I cared about was my family and my job. Why think about politics, if there is nothing you can do to change it.

However, some changes were evident at the beginning of perestroika. The first thing that drew my attention was that Soviet newspapers started covering events in Israel. Also, the manner of presentations changed a lot. While calling Israel an aggressor before, during perestroika newspapers became more objective writing about Israel. They also wrote that people in Israel were talented and hardworking. During the Soviet rule traveling abroad or visiting relatives was impossible, while during perestroika this became possible. My father's cousin sister lives in Israel. She must be 90 years old, probably. She invited me to visit her. I didn't visit her then, though for other reasons: tickets were expensive, and besides, my health condition didn't allow me to travel that far. I believe we've benefited a lot from perestroika.

In 1991 the Soviet Union broke up. It was hard to believe this could be true, considering how monolithic and powerful the country had been and then it disappeared all of a sudden. Estonia gained independence. I can't say unambiguously that it was good or bad. Everything has its pro's and con's. It's good that we live in our own country now. It's a good thing we can think by ourselves how we want to live.

However, there are some things I don't like about it. During the Soviet time people were free to move from one Republic to another. There were no borders separating them. Members of one family live in different regions. They are not so free to reunite nowadays. My mother's cousin sister lives in St. Petersburg, Russia. It becomes a whole problem, if we want to visit her. We need to obtain a number of papers and have visas adjudicated. It takes a lot of time and effort. Traveling to any country, but Russia, is easy. My mother cousin's birthday is in summer. She's invited us. My daughter has been busy gathering all necessary papers for herself and her son since winter. She's also saving for this trip. It's rather expensive. I don't like it that all roads to the FSU Republics have been closed for us.

Everything else is all right. Life in Estonia is gradually improving. There is no anti-Semitism in Estonia. In this apartment building we are the only Jewish tenants. The rest of them are Estonian, but they are very friendly, and very polite with me.

Our Jewish community was established in 1985. Now I can't imagine my life without the community. It goes without saying that the community supports us in the material sense. They deliver food packages to pensioners, partly pay our utility bills, particularly in winter, when our heating bills are so high. Now I have a higher pension. The state ensured that those who were in evacuation and those subject to resettlement had equal allowances and benefits. This includes partial coverage of the cost of medications, while before these were taken care of by the Jewish community. What can I say - this is a significant support.

Well, I think, the most important thing that the community does for us is getting us together. This is so very important. I have a family, but I enjoy visiting the community so very much. I like talking to people there. The community provides support and the joy of communication to lonely people. We get together on all holidays. We celebrate Jewish holidays, and they are always very nice. We also celebrate birthdays. Each month people having their birthday this month get together to celebrate. The community takes care of the treats, greetings and gifts. They may also invite their own guests to the event. It's very important for these people to know that they are remembered and needed. Therefore, the community has become a family for many Jewish people.

Glossary: