Lily Arouch

Athens

Greece

Interviewer: Annita Mordechai

Date of interview: November 2005

Lily Arouch, 77, has beautiful light blue eyes and wears glasses. She lives in a big apartment in the suburbs of Athens.

Since September 2005 she shares her apartment with her granddaughter Yvon, who has moved from Thessalonica to Athens due to her studies. In the same apartment block lives her older daughter's family.

Around her apartment are pictures of her family, her daughters, her grandchildren and her husband as well as her sisters' families. In the living room there is an impressive library, where one mostly sees history books.

The apartment is always full of little treats for guests or the family and it always has a delicious cooking odor.

Being her granddaughter myself and listening to her stories gave me a completely new perspective on the past of my family and life in Thessalonica.

- Family background

I don't know much about my great-grandparents. I didn't even meet my grandfathers, neither of the two. I did meet my grandmothers though before they were taken to the concentration camps. I believe that my father's family came from Portugal because they ended up in Monastir, a small town in Serbia.

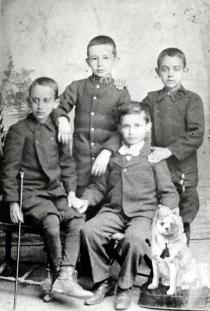

I don't know very much about my father's family. My grandfather on my father's side was named David Pardo and was married to Lea Kamhi. They had five children: my father and four daughters who were all born in Monastir, Serbia.

[Editor's note: After the end of the Second Balkan War in 1913, formerly Ottoman-occupied Macedonia was carved up among Serbia, Bulgaria, and Greece. Monastir was in the territory incorporated by Serbia; renamed Bitola it today belongs to the FYROM. (Source: Mark Cohen, 'Last Century of a Sephardic Community: The Jews of Monastir, 1839-1943')]

My father's mother, Lea, was a very traditional woman: she didn't go out much, she wore her traditional headscarf and she only spoke Spanish, even after moving to Thessalonica in 1914-1916. Of course Thessalonica was Turkish then; it became Greek only later on.

[Editor's note: Thessalonica became part of Greece with the Treaty of Bucharest in 1913. A few months later WWI started during which the city accepted the allied forces of the Entente; nevertheless Thessalonica was still quite Ottoman in nature.]

I guess she was very traditional but not religious. She wasn't very talkative, but she was very active within her household, she took very good care of us and was very important in our house. We lived in a house in the center of the city, so my family wasn't in a very Jewish environment; I guess the environment was more the Orthodox Christian environment of Thessalonica.

My grandmother didn't have much of a relationship with the neighbors but she was always waiting for Saturday when her daughters and grandchildren would visit; visitors were always a cause for celebration in the house. She used to live with us, but unfortunately she was taken to a concentration camp.

My mother's family, the Berahas, probably came from Spain and then settled in Skopje. My grandfather on my mother's side was called Solomon Beraha and was married to Doudoun Frances. They got married in Skopje but came and settled in Thessalonica.

I know that my mother's father was a pharmacist who had studied in Constantinople [today Istanbul, Turkey]. He went back to Skopje, but life wasn't good there, so they moved and settled in Thessalonica. My mother's father died at the age of forty, so I guess he was born around 1870. My grandmother Doudoun had another daughter, Laura, and a son, Gastone. My grandmother went to a nuns' school, so she spoke French and Spanish, which was her mother tongue.

My grandfather Solomon was a pharmacist, so when he got to Thessalonica he opened a pharmacy. When his son Gastone grew up, he wanted to renew the pharmacy; back then it was traditional for the children to take up their fathers' profession. So in 1917 he ordered new equipment for the pharmacy from Germany.

In 1917 there was a great fire in Thessalonica 1. After the equipment arrived, the fire broke out and everything, along with the pharmacy, burnt down, and they were left with nothing. The family, husband, wife and three children, was left without anything. In 1918 my grandfather died from appendix problems; he was forty at the time. His family was left without any means to survive.

My grandfather had brought the medication from Germany, and when one of his German associates learnt about the incident, he came to take my mother's brother Gastone with him to Germany to help the family. Gastone went with him to Germany at the age of eighteen. He was the one who supported the family financially; he was sending money to his mother for her to make a living and get the girls married and so on.

My grandmother Doudoun spent some time in Paris with her son Gastone, and then, before the war, she came to Thessalonica and stayed with her other daughter Laura; unfortunately the Germans took her away. Our family wasn't religious in the strict sense of the word, but they were very traditional: Saturday night was always a celebration; my grandmother Lea always lit the candles, without being too religious though. My grandmother didn't really go to the synagogue.

My parents were called Haim and Eugenie Pardo. They had an arranged marriage in 1928 in the synagogue in Thessalonica.

My mum, like her mum, went to a nuns' school, a 'l'ecole des soeurs' as they used to say, so she spoke French and Spanish and some Greek. Her Greek wasn't very good, but she managed.

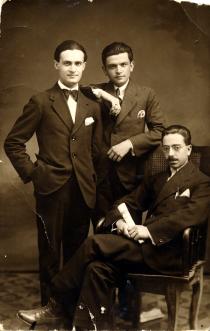

My father was born in 1898 in Monastir. His mother tongue was Spanish. In addition to the German language, which he probably learnt at the German school he attended, he spoke French fluently and also Greek. I don't know if he went to school for that, I think he learnt Greek by himself, but he spoke and wrote it very well.

He was also very keen on learning, he was a philomath. He was tall and thin. He wasn't very talkative, but he was gentle and decisive. He was always helping different charity institutions. I know he was a big patron of the Jewish institutions of Thessalonica, but I don't think he was ever a member of any political organization.

He was a self-made man; he came [to Thessalonica] from Monastir with his parents during World War I, probably around 1916-1918, and started working on his own. I guess his father was sick because he started working and fighting for survival very early on.

He started off as an employee and then founded his own business, a commercial shop named 'Pardiko,' on 28 Tsimiski Street. It was an electrical shop that sold electrical appliances and items, wires, leads etc, and even bathrooms and sanitary ware.

- Growing up

My parents' clothes were very European and contemporary for their times. They were no different than other people of that time. My mother was very elegant and chic. I remember that my father used to read a lot. I don't remember my mother reading, but my father really read a lot.

He was reading all sorts of books: literature and even political books, but not religious ones; my family wasn't very religious. He didn't use the library. He was working long hours. He used to read at noon when he came back from work. People back then, or at least my father, would come back from work, we would eat and sit and then he would read his newspaper, and then he would go back to work.

At the time they used to work mornings and evenings. He would come home very late at night. He reinforced us to read from a young age. We went to school, a Greek school, straight away, but we always had a French tutor in the house, because we needed to know a foreign language.

In Thessalonica other than the Greek newspapers there were also Jewish newspapers in circulation, published by Jewish editors. There was 'Le Progres' and 'El Messagero' and 'L'Independent' among many others. 'El Messagero' was Spanish. Two friends of his [my father] published two of these, and he used to read them every day.

Sam Modiano was the publisher of 'Le Progres' and Ilias Tas was the editor of 'L'Independent,' the two French papers in circulation in Thessalonica then. My parents used to read many foreign newspapers. My mother's brother Gastone, who had left for Germany when he was eighteen, left Germany in 1933, when the situation got worse for the Jews, and went and settled in Paris.

So they had good and direct knowledge of the situation. That, along with the information from the newspapers, made the atmosphere in the house heavy, as if we were waiting for something very bad to happen. We knew that in Germany things were bad for the Jews and were frustrated, as we didn't know what to do and how to do it. They were very aware of the situation in Germany and Europe, my parents as well as their friends.

My family lived in the center of town, on 35 Tsimiski Street; this means there was no Jewish neighborhood around us. We were living in a mansion- style house with five apartments, three of the families that lived there were Jewish. One of the families was called Gildi, they owned a big bakery in the center of the town; the other family was called Shalom.

It was with them that my parents were closer; they used to see each other socially once in a while. We lived in one of the apartments: my parents, their three daughters and my grandmother Lea. It had five rooms, my parents' room, my grandmother's room, which is where I stayed because I was the oldest daughter, the living room and the dining room, which were closed at that time, and one more room for my two little sisters.

I remember the furniture distinctly, it was very traditional. The beds were brass and very big, my mother's was gold-plated, I think, and covered with very big mosquito nets that we used to call 'baltakina' 2. We had them over all the beds, and in my grandmother's room.

These mosquito nets were quite luxurious with many layers of lace. They were important because there were a lot of mosquitoes back then. In my grandmother's room, along with the big bed there was a 'lavomano' 3, which was a big bowl with a porcelain jug. The dining room had a big buffet where they kept the silver tray with the silver spoons that they used when we had visitors.

They would take out the silver tray, the silver spoons and glasses and offer three types of dessert. My grandmother Lea was a renowned hostess, so when we had visitors she offered not one but three types of dessert.

We had electricity in our house and running water, we even had a boiler that would heat the water up with wood, and this was fairly sophisticated for our time. The electricity was used for lighting the house. As we didn't have electrical appliances at home, we would cook with charcoal and we had something like a fire cooker, in Spanish we called it 'formaiya' 4.

There was an entrance hall in the house like in most houses at the time. It was there that the 'salamandra' 5, a big stove that worked with charcoal, was. That is how the whole house was heated up and we had smaller wood burners in some rooms.

We used to have a girl that helped with the household chores and she used to stay with us; she mainly helped with the washing and the kitchen. We also had a teacher, who would take us for walks and look after us. We didn't have a garden, and we had no animals.

In the apartment next to us there was another family, the Negrepondis. Ambrosio Negrepondi was an insurer and had two children. His daughter, Maria, was the same age as my sister Roza; the two practically grew up together. Maria was constantly in our house when we had French lessons; she also took lessons with us.

Maria, our little Maria Delivanni, was a dean of the University of Thessalonica and is a respectable member of the society of her town. We still have contact with her, mostly my sister Roza sees her once in a while. It is her family that kept some of our belongings when we had to hide; it was them who gave us shelter during the first months of the liberation.

As for the town of Thessalonica during the post-war period I remember there weren't many cars, even though we lived in the center. There were a few cars and even fewer taxis but people mainly used horse carriages. There was the tram and this is how we mostly moved around. Where we lived was a very central place, so all streets around were of asphalt.

Near our house was a really beautiful square, Aristotelous Square, which had all sorts of coffee places around, and the cinema was there as well. That is where we would go for walks or play games, with our parents or without. Of course there were neighborhoods in Thessalonica that didn't have asphalt roads, and they were really poor.

We always kept Sabbath; Friday night was a very special night, and the same was true for Saturday. We always had someone over for dinner on Saturday, a close relative, a cousin or a friend. Every Saturday afternoon, [Grandma] Lea's daughters would come to visit her with their husbands and children.

Pesach was a very big celebration. We might not have been religious, but in our house tradition was sacred. First of all I remember that around Purim, which is exactly a month before Pesach, preparations had to begin. In those days we didn't have a mixer or anything like that, so when the sugar arrived in crystals, I remember my mother and my grandmother trying to break it up with a mortar and a pestle in order for the sweets to be prepared. The sugar had to be Pascoual 6 in order for the sweets to be proper. After that there was a huge box, it was more like a trunk, where they stored the Pesach pans and pots for the rest of the year.

On the eve of Passover these were taken out and all the rest of the household stuff was put away. The big trunk was sent to the matzah factory. Back then we didn't have the matzah cut in maneuverable sizes, bought in boxes; the matzah came in big pieces of differing size, in the trunk, covered with a white cloth. It had to last for the entire Passover period.

This matzah had to be cut down in order for all the sweets to be prepared, like the burmoelos 7, a very traditional sweet of Thessalonica. We kept the seven days of Passover and the whole tradition of it. For Passover, only one of my father's sisters, Ester, would come; the other three had big families of their own.

Ester lived near us and she came with her husband, Sabethai Pardo, and her two children [Nina and Alberto]. My mother's sister Laura joined us as well with her husband - the rabbi's son - and we all sat together around this traditional table.

As for Rosh Hashanah I remember the festive table. It might not have been as intense as Passover, but it was a big celebration for the family. We followed most of the traditions. There were the traditional Rosh Hashanah dishes; like the fish of which each one had to have his own as a symbol of his/her self-sufficiency, and the fish-head that symbolizes our path, our forward path.

Then there was the leek, we would make it into leek balls. We heat up the leeks and dry them very well, we add some breadcrumbs, salt and pepper and some egg. Then we make the mix into balls and put them in the frying pan [traditional Sephardic recipe].

There was spinach we would make into pies, and of course there were the dates. I still make the traditional apple sweet of Rosh Hashanah, not only for myself but also for the whole family and friends. The recipe is as follows: About 1.5 k of apples and 1k of sugar and a glass of water. We dissolve the sugar in water and quickly add the apple after we have peeled and grated it. We add some lemon so that the color stays and leave it on the fire until it settles. We leave it to cool and then we add almonds and we put it into jars [traditional Sephardic recipe].

On the night of Rosh Hashanah we say, 'Let the new year be as sweet as honey.' It is traditional to have the apple sweet on that night in order to wish for the year to be as sweet and nice. My grandmother and my mother used to make this sweet for everyone in the family and sent it to them.

Yom Kippur was the only day my father spent the entire morning and afternoon in the synagogue. He would return home in the evening, and there would be a sort of feast. It was a very respected day for everyone in the house; my mother would spend it absorbed in prayer and we, the children, would try to keep the fast.

It was my father who went to the marketplace, the Modiano market [built in 1923 by the architect Eli Modiano, who was the son of a well-known banker, Saoul Modiano]. He would go out in the morning to shop. He always had one of his employees with him. He would shop and the guy would bring the stuff back home.

My father would buy all the special items, like fish or meat. The grocer would send his helper around the house and my grandmother would order the rest of the stuff that was needed. It would be delivered later on in the day.

I have the impression that the merchants at this market were mainly Jewish. There was this central marketplace, the Modiano market. This market still exists in Thessalonica and it used to be the food market of the town. I remember it used to have three or four corridors where different kinds of shops were situated. You could find fish, meat and vegetables. It is my impression that lots of the shopkeepers were Jewish.

There was a very active Jewish community in Thessalonica. When I say active I mean it had many charity institutions to help the poor; as the community was so big, it had people from all social classes. There were lots of poor people, entire neighborhoods, and I know that the community would take care of them. It had institutions, old people's homes, orphanages, institutions for poor girls. There was also a big hospital named HIRS that was built by Baron Hirs, who was known throughout the Balkans. It was a big hospital and I think it still exists. There was the Mair Aboav; I think that was the name of the orphanage, Matanot Levionim 8, the Saoul Modiano care home.

I don't know how many rabbis there were in Thessalonica, or if there was a shochet or chazzan. There were Jewish schools, but my sisters and I didn't go there, so I don't know how many Jewish schools existed.

I don't remember the political atmosphere so much as I was too young. Before I was born there was a fire in Cambel. This group that was called 3E 9 had burnt a whole area but that was either before I was born or when I was really young.

Of course we were very annoyed with the dictatorship of Metaxas 10. He had established E.O.N. 11 in which he made very clear and obvious he would not accept Jews. I remember my parents and their friends were very upset. I don't remember any parades.

In Thessalonica there were two different views among the Jews: one of the two groups believed that everyone should leave and go to Palestine; they were called the Zionist movement. The others held the view that they should try and be incorporated in the society they were living in. My father supported the second view; he thought efforts should be made to assimilate with the Greek society.

My parents' friends were all Jewish and had similar views. They would talk to my mothers' sister and her husband, with my father's sisters and their husbands and other friends, but they were all Jewish. They would come over or go out probably to other people's houses or somewhere outside to sit and chat.

All [friends] I remember are Zak Franses and Alfredo Beza, who survived the war, and also Salamo Arditi, who was consul of some country - I don't remember which one - but he helped my father during the war because of his position, I guess. The first week the Germans were there they informed the diplomats that they would open the banks for two hours.

Everything my father owned was in a safe in the bank. His friend Salamo notified him and my father managed to join the diplomats and salvage all he could. He was always very grateful to his friend that he owed a big favor to; they spent a lot of time together. I also remember Pepo Beza, who was also a good friend and a merchant too.

My father's associates and colleagues were mainly Christians and even though they had very good relationships, we didn't have closer family-like relationships with them. I remember that our family would never go on holiday.

My mother's sister was called Laura and she was married to David Haguel, who was a son of Ha Giako Haguel, the great rabbi of bet din. The bet din was the supreme Jewish court and I remember that when the rabbi died the whole community was really shocked; he was a very important figure at the time.

My grandmother Lea had a sister in Thessalonica called Mesulam - Luna Mesulam Tamar - my father would go and visit her once a year during Passover. My other grandmother Doudoun had a sister who would occasionally come and visit us; her name was Myriam.

I was born in Thessalonica in 1929. My mother took care of my two younger sisters and me even though we also had a teacher that looked after us. My grandmother did the cooking. I went to school when I was six, the Valagianni School; it was all girls, but I don't remember making any special friends. We had a lot of lessons at school and also French lessons.

We would go to school in the morning, come back around one, have something to eat and go back at three o'clock, then we would go back home at five, and at five thirty our French teacher would come.

After that we had to do our homework. When I was a bit older, about eight or nine years old, I would try and finish my homework earlier, so I could go to my father's shop, which was very close to our house. We lived on 35 Tsimiski Street and the shop was across the street on 28 Tsimiski Street.

I really loved going to the shop because I really enjoyed being close to him and also watching and listening to what they were doing. I remember that we were very busy [at school] and had no free time. We would go to school even on Saturdays, although it was Sabbath and my aunties used to come over.

I clearly remember the headmaster of the school, Ms. Valagianni. When things got worse in Thessalonica she called me into her office and said, 'my child I understand that now you might not be able to come to school, but you should know that whatever you want I am here and you can come to me.' At that time something like that was very important and I still remember; it gives me the chills. People in my school were nice, and I don't remember any anti-Semitic incidents.

I went to the same school as my sisters; I remember we used to play a lot. We would never go to the synagogue, only if there was a wedding or some other event. Of course we had a beautiful synagogue of the people from Monastir [see Monastir Synagogue] 12, where my father came from, and which was being maintained.

My father always went alone to the synagogue; he never took us with him. Every Sunday my parents would meet up with other couples who had children our age; they had about two or three friends like that. They would talk to the grown-ups and we played with the children, who were pretty much our age. All these friends were Jewish. I didn't do any sport, and then, unfortunately, I was eleven when the war started and I couldn't do anything after that.

I went on a train journey once with my mother; we went to Paris in 1936. It lasted for three days and three nights, from Thessalonica to Paris, and I remember it very intensely. When we got to Paris we were grubby from the smoke in the train.

Our parents didn't teach us anything directly but their example was intense. I mean how nice they were to their friends, how caring they were to the family; my father was always worried about the family and my mother would take very good care of her sister. It was these things that were important for us.

Looking back at my family environment, I believe that we were a middle class family and there were two basic things: the first was education, where every generation would reinforce the next, every generation was more educated than the last one because there was a will to learn, a will to teach the children.

My father and his sisters went to school, of course, but then they continued getting educated and the same was the case with my mother's family. The second thing I think affected this family was immigration: in all the families there was someone that left. As for my father's family, two of the five siblings went to North Africa.

In my mother's family their support was the brother in Germany. In my husband's family, out of the four siblings two left looking for a better life: Morris, who went to France, and Mordo, who went to Skopje. There he created a company. All in all, the basic similarity was a will to better their lives.

- During the war

For me the war started on a Monday morning, it was the 28th of October 1940. We were very scared; we had heard that the Italians would bomb us. Our house had four floors, so we arranged it with the neighbors and went and slept in the basement on makeshift beds and mattresses.

Three days went by, but then we started going out a little bit. Of course we weren't going to school then because we were scared. On Friday morning the alarm went off and fortunately we were all home, except my father, who was at work. We were with Mother and we didn't know what to do, so we gathered in a little corridor in the basement.

My father stayed at work. Then really loud bombing started; it was probably so loud because we were in the center, opposite the post office. As we were in the corridor, we could actually feel the bombing; it really was that loud. We didn't know what to do.

Anyway, when this whole thing was over we realized by looking out the window that it was our father's building that had been bombed. Luckily for us, the other side of the building was the one that had the damage, and so he was saved.

After that my mother and father decided we would move to some little house outside Thessalonica, in the countryside. They said it was impossible to live in the center and especially as central as we did, on Tsimiski Street. So we put some mattresses and some clothes on a horse carriage.

There was no other means of transport, so we took the tram: it was my parents, the three children and my grandmother who had real difficulty moving. During the tram journey the alarm sounded, we got off and went to a basement because there weren't any shelters; things weren't organized at all. My father and the neighbors paid to make a shelter, so when the alarm sounded we would hide there, even though we were outside the city.

My father still went to work, even with one half of the building having been bombed. In another incident I remember, there was a bomb that fell into the courtyard of my father's shop and it didn't go off. Usually, the employees would hide in the basement during the alarms, that time they were extremely lucky because it didn't go off.

They called the police to deactivate the bomb. Imagine, they had to empty the whole square because they were very scared. They even marked the day by writing the word 'black day' somewhere. Thankfully they managed to deactivate the bomb successfully, and our father was saved, thank God.

We remained in the countryside until April or May when the Germans came and we had to go back to our house. After that our trouble with the Germans began. The Germans entered Thessalonica in April 1941. For about a year they were slightly tolerant and life went on normally, even though we were terrified.

We stayed in our house in the center that whole winter of 1940- 1941. The Germans would often order the whole town to stay inside their houses, and sometimes they would choose a house and enjoin it. In our house they took over one room and accommodated a German officer there, which obviously caused us a lot of problems.

My parents wouldn't let us out of the rooms. A bit later on the Germans took another two rooms, so they had three in total. My family was limited to two rooms. In the other three rooms lived a German family. The situation went on like this for about a year.

In July 1942 an order came out that all Jewish males aged eighteen to forty- five had to gather up at Eleftheria Square. My father was quite clear from the beginning that he was against that and he refused to go. My mother was very scared because they were making known the penalties for not showing up. However, my father still refused.

As I was the oldest daughter, they decided that I had to go and see what was happening. I was thirteen then. I left and went to Eleftheria Square which is surrounded on three sides with tall office buildings and the sea on the other; I went on a balcony of one of those buildings, along with many other people. I was too young and no one noticed me. I guess the people around me were all Christian.

The view was horrifying. It was a square full of men without tops or hats and the sun was burning hot. They had been lined up on the central side. The Germans were positioned in front of a big bank and they were making rounds and pointing at people. They would shout, 'you, you' and make them do cartwheels and hit them.

They forced them to stay there for many hours until the sun went down; they were standing since dawn and being tortured one after the other. I have to admit I was terrified and I went and told my father what I had seen, which made him refuse to go more firmly. I was proud that my father didn't go even though there was great propaganda against such behavior. Anyway they were all let free that night.

Then there was an order that those who hadn't gone to Eleftheria Square should go and present themselves in some school buildings. Things were getting rough, so my father decided he couldn't avoid showing up in a Jewish school. It was a bit outside the town; I went with him.

There must have been about a hundred people gathered there. Again they had to walk in the sun until they got to this place by the coast, Aretsou maybe, I'm not sure. They were put into line and they all went through a series of doctors; supposedly they were the ones with health problems. My father was relieved because obviously something was wrong with him, and he didn't have to go for labor like the ones before him.

As time went by the Germans gathered more and more Jews and had them working, building roads at Lamia 13. A lot of children died from malaria; there was an epidemic at the time. At some point the Jewish Community of Thessalonica gave a large amount of money, gold liras, to stop the hunting down of the young people, and the sickness. I know that my father gave a significant amount for the cause, but nothing happened.

The situation got worse: the winter of 1941-1942 was the winter of hunger, as they used to call it. It was very hard because the Germans had confiscated all the food. It was very cold, we had no heating and we stopped going to school. My father still went to work, but business was very limited, no one was really building or fixing anything, and the Germans claimed a lot of the merchandise too, just like that.

In February 1943 the real persecution started. It was then that our neighbor, Maria's father, came to discuss with my father how they could save their children. When the time came and we had to leave, they were really close to us. First of all we gave them all our carpets and the pianos were moved from window to window, and these are the only things we managed to save.

The rest of our furniture was never found. Some people said that some of our pictures eventually turned up in some basement. Someone who knew my father put them in a bag and gave them to him. So these were saved very randomly.

In April 1943 we were forced to wear the star of David, even the children, and we were moved to the ghetto. There were two ghettos in Thessalonica, one by the train station and one close to the countryside; we went to the second one [see Thessalonica Ghettos] 14. In the ghetto each family, regardless of how many members, had one room. We spent about two months there. The bad news just kept on coming: they started arresting and sending people to the train station ghetto and then put them on trains and shipped them off somewhere.

The situation was getting worse and by manipulating the community and the head rabbi Koretz, the Germans selected a hundred well-off community members, including my father, whom they called 'hostages.' They were responsible for the people that tried to escape: for whoever would try to run, one of the hundred men would be executed. A lot of people would come by the house and a lot of them had a compromising attitude. They were saying that it didn't matter, if they were shipped off to Germany, it would be the same, 'work here and work there.' They had their older parents to consider, as they said.

This young man, an employee of my father and cousin of my mother, Alberto Kovo - he was about twenty eight years old - came to the house one day. My father told him, 'what do you think you're doing? You are a young man you should go.' He said, 'I can't go, it doesn't matter if I work here. I will work here. I can't leave my mother.' At the same time there were people that were more dynamic. They would come and say, 'we won't bend down our heads to the Germans. God knows what they will do to us.'

My father knew very well what was happening in Germany and he would discuss it with other people. He knew it because he was aware of things, he read a lot of things about how bad people were being treated. Obviously he didn't know anything about the crematoria and the concentration camps, but we knew about people being treated badly, we were living in such conditions.

One day my father received a message from a friend, a doctor, George Karakotsios. It said, 'I am willing to put you and your children up so long as you manage to leave that place.' My father didn't think twice, even though he had to leave behind his old mother, and my mother had to leave her mother and sisters and their families.

On 12th April 1943 I left the ghetto with my two sisters; we stayed alone that night. Before we left my father told me, 'Listen child, you have two younger sisters and you need to take care of them.' We didn't know what was going to happen next. Thankfully my parents came the following night and then the morning after that everyone in the ghetto, where we had also been before, was gathered and taken to the ghetto next to the train station.

From there they were forced into trains and left. My grandmothers and aunties were taken too. We found that out when we were hiding, because we had a Christian friend who would come and tell us some news. We remained hidden in that house for nineteen months, even though the original plan was to move further away from the center. The apartment was very central, it was on 113 Tsimiski Street, on the third floor. It was an apartment with three rooms and the people living in it were the doctor, his wife and their child.

These people saved us, they were very special. He was a known tuberculosis doctor, George Karakotsios. He was the manager of a branch of IKA [social security office] in Thessalonica. His wife was Fedra and they had an eight- year-old boy then.

These people took us in, gave us their room and hid us there for nineteen months. They shared with us the little bread and food they had, and also our fear and frustration. It was a very hard time for us, and for them. We were all very scared. Imagine, we were living in a very small apartment and every sound and every knock on the door was scary for us. My father was hiding in a closet and my mother was hiding under a bed.

We also found out afterwards that the building opposite was a partisan hideout, so we would hear 'boop boop' and it was the boots of the Germans going to search that apartment. Twice we really thought they were coming for us, so my parents left in the night. Back then there was a curfew, so the streets were completely empty.

We were left in the house. On the one hand we were fine, because we were living in an apartment, but on the other hand we were scared too. We would walk with socks because we didn't want the people living below us to know how many of us were living up there. Obviously the lady of the house would go out shopping for the family and obviously it was quite basic: we didn't have much money; my father had some but not that much. We were just trying to survive.

We were eating pulses; I rarely had meat that whole time. There was a shop close by that made yogurt of terrible quality, our hosts would buy some and they would share it with us and a piece of bread. That was dinner. For lunch we would have pulses or a potato - very basic.

That period we weren't keeping Sabbath or any of the holidays we didn't even know when they were, my parents would calculate it could be [Yom] Kippur, but there was no way we could keep it. My mother and I would do all the housework, we would wash the clothes by heating up some water on coal and briefly try and clean them.

We would make bread if there was flour, and we were all allowed one piece each. The bread that was available at the time was called 'bobota', a kind of hard corn-flour bread, that's what the bakeries were selling. Time went by and my mother would wash and cook and keep the children busy; my younger sister was three years old.

My father was reading books from the doctor's library and I was too. I was reading a lot, both the doctor's and his wife's books. Or I would knit if there was wool, so I could make some clothes for my sisters; they had nothing to wear and there was no chance we could go out and buy any [clothes].

Naturally they [Dr. Karakotsios' family] limited to the minimum the people that visited them. Only a friend of my father's would come every fifteen to twenty days to see us and tell us what was happening in the outside world. Time was going by slowly and we were hearing stories about people getting arrested and we were very scared.

Then there was bombing in Thessalonica and I remember being in the room and watching the port on fire. We really were very grateful to these people; until the day she died my mother called George Karakotsios an angel. The Karakotsios' though were hit by a great misfortune. After the liberation my parents would see them sometimes.

Their son, who was aged about eight or nine, like my sister Rosa, grew up and became a soldier. He was their only child. One day his mother saw a military Jeep come by with two coffins. They said, 'we brought your son.' She went crazy and jumped off the fourth floor and died. Mother and son were buried the same day. The father was a wreck and didn't live more than another year or two. This was a terrible ending to this family and we were very hurt by what happened.

- Post-war

When the war ended in October 1944 [12th October 1944], we saw the Germans leave in their trucks; we had a little window and we could see what was happening. Once again they sent me out first, to see what was happening. When I came back I told my father, 'I don't see any Germans, I think you can go out.' And so we left our hiding place. We had stayed there from April 1943 to October 1944, we had been there for nineteen months. After that we left the hiding place and life went on.

When we were liberated we found out that my grandmothers and my parents' sisters were all dead. The only one who was rescued was one of my father's sisters, Ester Pardo, with her husband, Sabethai Pardo, and her daughter, only because her son was a civil guard 15.

During the war the community had organized a few young people with the promise that they would be treated better, if they became civil guards.

My little cousin, who was twenty, joined them, and he helped bringing a group of people to the trains. A person from that group escaped. When the Germans counted them and realized someone was missing they took him instead: he was sent to Lamia, to forced labor. He tried to escape and was shot in cold blood. His parents went out looking for him; they left the ghetto and were saved.

In addition we learnt that Gastone had been saved. He had an adventure but was lucky. In 1939 Gastone had already moved to Paris and had been married for a year. His wife was expecting a baby and wanted to go back to Cairo, to her mother, to give birth.

Gastone and his wife left for Cairo where they ended up spending the entire period of the war as they couldn't get back to Europe and had two children: Deniz, who was born in 1940, and Mony Beraha, born in 1944. The family returned to France in 1948 and Gastone managed to establish himself as a pharmaceutical merchant. He lived all his life in Paris.

When we left the house we were hiding in, we only had a little suitcase with very few clothes, and as we had nowhere to go we went to a hotel. We went back to our old house and there was nothing. There were some refugees living there already, the house was empty and there was nothing in it.

My father went and bought five plates and five forks and a couple of knives so we could sit and have something to eat. We stayed in that hotel and then moved to a better one, which was called 'Modern.'

On the second day my father went out to see what was going on in the town. His shop was completely empty, there was nothing left. Everything had been evacuated by the Germans. Our house had been completely emptied of our things, so we really didn't find anything.

Many refugees had come in from the provinces around. While we were hiding the rural areas were severely suffering from the Germans. It was these people that had occupied our apartment. They were moving into any empty house or apartment they found.

My father, probably out of anxiety for the future, or sorrow, or both, went through a paralysis. He was unable to move and so stayed in the hotel room for a while. Everyone said it was psychosomatic stress he was going through. It was probably a combination of the fact that he had been lying down for nineteen months in the house that we were hiding in, and then he suddenly started walking and moving, and the chaotic situation when we came out. We didn't find anything, neither our house nor our furniture nor the shop and its merchandise. Thank God he recovered in the end.

On our return from hiding the reaction of our neighbors was mixed. There were those who were happy to see we had survived and those who had a peculiar attitude saying, 'oh, so you were not taken away, were you?', as if they were happy to have got rid of us.

The community had not been reconstituted yet. We were among the first ones to come out on 26th October, and then slowly people started coming down from the mountains. In Thessalonica we found a doctor named Matarasso who hadn't been persecuted as he had a Christian wife. The first meetings were held in his house, at night we would all gather there: my father, the doctor and anyone else that had returned, either from hiding in the mountains or the villages around.

My father tried to reestablish himself in Thessalonica, where we stayed the entire winter of 1944-1945; it was very tough. That winter he tried to restart his business without merchandise and money. It was his acquaintances from before the war that helped him.

My father owned the building where his shop was. In the meanwhile one of his associates came back from Germany - his name was Ovadia Medina - and another one named Leon Carasso returned from hiding in the mountains. The latter was to become my brother-in-law later in time. On their return all three of them tried to reestablish the business and get back to work.

This new venture expanded and when we came down to Athens, my father created an import office there. That way he was providing the shop in Thessalonica with merchandise. This business was very successful all through the post-war years until my father's death.

I believe that after the war my father clearly became pro-Israel, which was an impressive change of view. The state of Israel was founded in April 1948, which was a great relief for us as messages from the concentration camps had started arriving.

[Editor's note: On 14th May 1948, the day the British Mandate over Palestine expired, the Jewish People's Council gathered at the Tel Aviv Museum, and approved a proclamation, declaring the establishment of the State of Israel. The new state was recognized that night by the United States and three days later by the USSR. Source: Howard M.Sachar, 'A History of Israel: From the Rise of Zionism to Our Time,' Alfred A.Knopf, New York, 1982.]

When the first survivor came back from the concentration camps, a man called Leon Batis, he came to Dr. Matarasso's house where we all met up and when he started talking about the crematoria and human fat being turn into soap and all these things, everyone was staring at him and saying, 'poor guy he is mad, hardship made him loose his mind.' That is how unbelievable it all seemed. Later more and more people started coming back and what was happening in the camps became well-known.

This is what made all of us, my father as well, realize that it was only on Israel we could rely. Since then he became a very eager supporter of Zionism. The American Joint Committee [see Joint] 13 was very active in Greece at the time. They came to help and they actually did help a lot of people.

After the war there weren't many friends or relatives left, some never came back and some started immigrating, mainly to the USA but to Israel as well. It was mainly younger people that left. To get to Israel wasn't easy at the time. The British were arresting everyone in Cyprus and putting them in concentration camps until they were allowed entrance to Israel.

I imagine we didn't immigrate because my father wanted to continue his business and he didn't want any more adventures in his life. He felt he was responsible for his family, and he felt he had something to start from here in Greece: his shop and colleagues. It was mostly the ones that lost everything - their houses and their jobs and their families - that took the decision to immigrate. My father was lucky enough to have had a base, and so he tried to rebuild the situation. As soon as we arrived from Thessalonica in 1945, my father's old colleagues in Athens helped him substantially; they gave him the means to start sending merchandise back to Thessalonica.

Our family moved to Athens. My sisters carried on with school, life carried on normally and naturally.

Socially, of course, my family remained within a Jewish circle. The girls [daughters] had their classmates but always kept their Jewish circle of friends. My parents' friends were all Jewish and so they could talk about their own problems and issues. Life went on, but unfortunately I came out of the occupation with a health problem; I had a hard time for a very long time. When my health got better, around 1950, I started working at my father's office and that is where I retired. I had to stop working because of health reasons.

My husband's family and mine had known each other for a while. That is how we ended up being introduced. His name was Manuel Arouch; he was born on 7th April 1911 in Thessalonica. His mother tongue was both Spanish and Greek. He was Jewish, and a doctor already when we got married. We got married in 1952.

Our wedding took place in a synagogue in Thessalonica, the rabbi, Morris Halegua, performed the ceremony. It was a small but traditional Jewish wedding, very moving. Without many relatives because neither my husband nor I had big families any longer. There was his older sister with her husband, Gracia and Leon Carasso, his mother, Sonhoula Arouch, my parents and my sisters. My wedding dress was very beautiful, it was a present from my mother, and I still keep it as a memento or reminder.

Before the war my husband's family was made up of four children, their father died when Manuel, my husband, was a high school boy. They were financially tight, but they all had an inclination or talent for learning. They were all educated. The older brother, Mordo Arouch, went to Skopje where he started a commercial business.

He got married there and had two children, Pepo and Alice. The children must have been around 15-20 when the persecution began. The Jews that were caught in Skopje were put on a boat to cross the Danube. The family found all this out later, after an official research in the archives of the concentration camps took place; there was no record of an arrival of a riverboat in any of them.

The other brother, Morris Arouch, left for France. Morris was a printer by profession; he read so much. He was married to Julia. He left for Marseille in 1930 in search of a better life. He worked really hard and in 1932 he called his wife to join him. They made a beautiful family there and had three children, Odet, Joseph and Alice.

The family had no other means and so both brothers, Mordo and Morris, and the sister, Gracia, helped my husband financially through his studies. They were sending him money each month. He had left Thessalonica in 1932 to come to Athens to study; he spent most of the occupation period in Athens. He was organized with the progressive youth organization of the university and the occupation period was hard for him as well as for all students; they survived on student commons.

When the persecution began, the student union joined NLF 17, which helped them a lot. My husband was with the group of people that helped the chief rabbi of Athens to disappear and burn the archives of the [Jewish] community of Athens.

The Germans put pressure on him to give them the list of the members' names, so they could record and arrest them. My husband was in the team that got close to the rabbi and convinced him not to consign the archives. He escorted him one night away from Athens to hide him and eventually send him to the mountains. Manuel went along with him and hid in the mountains.

During that period he was a member of NLF and then in ELAS 18, all the years of the persecution he was in the mountains of mainland Greece. He worked as a doctor while he was there, he took care of the rabbi; during the war he was protecting and taking care of him.

The first years after the liberation he worked for the [Jewish] community of Athens, he was the one who helped all the people that came back from the concentration camps or hiding. Later on he was employed by Joint and he created a multi-purpose medical office on the premises of the community of Athens; he worked there for many years. The work they did there was very important, as most people came back from the concentration camps either sick or very weak. They would take care of them, place them in sanatoria and give them the proper medicine. Joint had brought medicines from the USA and so people got substantial help.

Family ties were very strong during the post-war years when Manuel started practicing his profession. His brother, Morris, lost his wife to a fatal illness. Morris was left alone with three young children and no house to his name. The first money ever made by my husband was immediately sent to Marseille for Morris to buy a house.

Morris' three children are still in Marseille, and are true to the Jewish traditions, despite the fact that the two girls had a civil wedding to people of other faiths. We still see them once in a while. My husband earned his first money while he was working for the community of Athens.

My mother-in-law, Sonhoula Arouch, was a woman of quality; she survived the war hiding in the mountains. Before the war she lived with her daughter, Gracia, and her son-in-law, Leon Carasso. Leon had known and collaborated with my father before the war. He was very well connected and from the first moments of the occupation he made clear he was not going to follow the Germans.

He took his wife and mother-in-law and left for the mountains. His mother in law was 70 at the time but still followed her children. There she was looked after and taken care of by all, but she was the one to look after the sick and feed the weak. She was known under the nickname 'Comrade Katina.'

Every time the partisans had to move further up the mountains, because the Germans were coming close, they all had to walk while 'Comrade Katina' was always on a donkey or a mule. She was the oldest woman from Thessalonica to have survived; during the liberation most people called her 'Nona.'

My husband and I lived most of our lives in an apartment in the center of Athens, at Exarheia. My parents had their own house in a different area in Athens. My husband's mother Sonhoula lived in Thessalonica with her daughter but came to stay with us once for a couple of years and another time for three years.

I had two daughters with my husband: the first one, Aliki, was born in 1955 and the second one, Nelly, in 1959. They both went to the Jewish Elementary School of Athens. I believe that the fact that they went to the Jewish school was an essential part of their education, not to say that my husband and I didn't contribute.

As long as my daughters were still young and went to the Jewish school their friends were mainly Jewish. In high school they started having friends of different faiths but always kept in close contact with their old friends. We both talked a lot to them about everything we were interested in and read a lot.

We always bought new books and took our children to the theater; I believe we had a very close relationship with them. We both spoke to our children about their Hebrew background and as they were at the Jewish school they knew a lot about Jewish traditions already.

Every Friday night we celebrated Sabbath, lit the candles, and on Saturday no one did a lot at home; it was kind of a holiday. The Jewish school took the children up to the age of twelve to the synagogue every Saturday. They went to the Jewish summer camp and took part in the organized excursions of the youth club to Israel.

As I have said, our friends were mainly Jewish and so the conversations were mostly about what had happened during the war and the situation at the time. Our children were never excluded from such conversations; they knew most things from an early age. I remember there was a really interesting French magazine of Jewish content that we subscribed to, called L'Arche. Of course we always read a national Greek newspaper in order to keep informed about our country.

My husband mostly read history books, whatever had to do with history he enjoyed reading; he read books by left-wing orientated historians as well as right-wing ones. I mostly read novels and studied English.

We always took part in the happenings that the Jewish Community of Athens organized, but we also went to the theater and to lectures taking place in town. We went on holidays for just a couple of weeks and always around Athens, as my husband worked very hard and didn't have much time to spare.

At home we spoke Greek among ourselves, but the grandparents spoke Spanish, so the children learnt Ladino by listening to it. Today both of my daughters speak Ladino and Greek. We tried to raise our children firmly within the Jewish traditions. For Pesach we invited all the family and friends to our house, even though it wasn't very big.

We always kept Yom Kippur and even my husband didn't go to work on that day, and for Rosh Hashanah we went with all the family to my parents' house. We never celebrated Christmas or Easter at home, but as the children didn't have to go to school it was almost like a celebration.

I still keep my cooking traditional, just as I learnt it from my mother. I try to preserve the traditional way of cooking without being to strict about it. My favorite dishes are the soup called 'Matsa al Kaldo,' as we say in Spanish, and all kinds of pies. I believe I am more traditional than my mother was.

My husband and I used to travel abroad fairly often, firstly for health reasons and then because my husband had his brother Morris Arouch's family in Marseille. They were very close, these two, and so were both of our families. We were also going to conferences and always went to visit the family.

My husband had many non-Jewish friends among his colleagues, with whom he always had very good relationships. On my side the biggest percentage of friends was Jewish. As a family we had friends we had known for a long time. My husband's sister lived in Thessalonica. Still we were very close, she and her husband used to come to visit us in Athens quite often.

We used to have very close contact with my sisters' families, who lived in Athens as well. We used to see them once a week, on Sundays, when we used to go on excursions. It was we and our children and my sisters' families as well as some family friends with their children.

We had found a field somewhere in Attica and we went for picnics, because not only could we not afford to go to amenity centers or clubs, but we didn't like it either. We preferred to prepare some snacks to take along, and I remember we were having a great time. Our children became very close to each other as they played together every Sunday and we, adults, had the time to chat about our things.

We were always talking about issues concerning Israel and Judaism to our children. These issues were always of our interest, and we were following whatever was going on in Israel, as the times were hard then. There was no one in our social circle that wasn't willing to discuss such issues.

As for my daughters' bat mitzvahs I remember them being very simple but emotional ceremonies. We never had arguments with the grandparents on the way we were raising our children; they were tolerant and not very religious themselves. We always sought for the grandparents to light the candles on Sabbath.

My mother died on 20th June 1973 after a fatal accident, and my father died on 16th May 1976 of a heart attack. Both funerals were held in the Jewish Cemetery of Athens, according to the Jewish laws and traditions. My parents- in-law are buried in the Jewish Cemetery of Thessalonica. A Kaddish was recited and we still keep 'the day of remembrance of the dead', Yom Hashoah [Holocaust Remembrance Day].

My younger daughter, Nelly, had a very painful experience. Since she was a child she had wanted to become a teacher. When she finished school and was about to take the exams for the training college, she was told that it was impossible for her to be accepted because she was Jewish.

So she wasn't allowed to teach in a Greek school! That was a major shock for her, as she had grown up with that dream, and so she decided to go to Israel. I escorted her, we were together when she registered, and I must admit I found it hard to leave her there on her own, in a foreign land. That is not to say I wasn't happy she was in Israel, but I couldn't avoid being overprotective, I am a mother.

Our house was always open to our children's friends, my husband was very tolerant and he really enjoyed seeing them. Whenever they were to go out their friends would come and pick them up from the house, and so we were always trying to guess who the future groom was!

My daughter Aliki lives in Athens and I have the pleasure to live close by, not in the same house but near. She has two daughters, Annita and Lily, 25 and 23 years old, respectively. Nelly, my other daughter, is married in Thessalonica and now lives there. She has Yvonne, who is 18, and Ben, who is 17. I have the pleasure to see my grandchildren often enough, and I also speak to them on the phone very often.

Nelly now works for the Jewish Community of Thessalonica, specifically coordinating the youth programs, so the kids [my grandchildren] from Thessalonica, because of their mother's profession, have a closer relationship with Judaism.

My grandchildren in Athens are less involved in Jewish life, as they live far from the center, although their parents are active community members. My granddaughters are not very religious or traditional but it doesn't bother me, as parents are the ones to judge what is best for their own children. All my grandchildren attended the Jewish elementary school.

I have been involved with WIZO 19, which is a women's organization that helps Israel, for a long time now. I have been very active and take part in everything we do: conferences, workshops or bazaars; I also try to financially contribute as much as I can.

Moreover I take part in most community-organized events, and whenever there is a lecture I go. Every 15 days I meet up with my friends from WIZO, which is a great pleasure for me. In addition I meet up with my sisters once a week at least. I still cook. These days I go on vacations along with my children, as I cannot go on my own anymore. It gives me great pleasure.

- Glossary:

1 The Fire of Thessalonica: In the night of 18th August 1917, an enormous fire, fed by the famous Vardar wind, destroyed the city centre where most of the Jews lived.

It was a region of 227 hectares, where 15,000 families lived, 10,000 of them were Jewish families which were deprived of their homes. The Jews were hit the hardest, since more than two thirds of the property destroyed by the fire was Jewish and only a tenth of that immense fortune was insured.

Nearly all the schools, 32 synagogues, 50 oratories, all the cultural centers, libraries, clubs, etc. were annihilated. Despite of the aid of a sum of 40,000 golden pounds collected from all over the world, the community never recovered from that disaster.

The Jewish face of the city that had been there for more than five centuries was wiped out in 36 hours. 25,000, out of 53,000 of the stricken Jews that belonged mostly to the lower and middle class, were forced to live in the working-class districts that were hastily built in a rudimentary fashion. (Source: Rena Molho, 'Jewish Working-Class Neighborhoods established in Salonica Following the 1890 and the 1917 Fires,' in Rena Molho, 'Salonica and Istanbul: Social, Political and Cultural Aspects of Jewish Life,' The Isis Press, Istanbul, 2005, pp.107-126.)

2 Baltakina: very big mosquito net

3 Lavomano: jug and bowl used by people to wash their faces

4 Formaiya: Big benches with hole-like stoves where charcoal was placed. It was used to cook, sometimes a big baking sheet was placed on top of it.

5 Salamandra: big stove for heating the whole house

6 Pascoual: appropriate for consumption during the week of the Jewish Easter (Pesach or Passover), a time when the Jewish people do not eat food that raises, e.g. bread.

7 Burmoelos (or burmolikos, burlikus): A sweetmeat made from matzah, typical for Pesach. First, the matzah is put into water, then squashed and mixed with eggs. Balls are made from the mixture, they are fried and the result is something like donuts.

8 Matanot Laevionim: (Hebrew: Gifts to the Poor); a philanthropic institution, founded in Thessalonica in 1901, with the aim to distribute warm soup to poor schoolchildren without means.

9 3E (Ethniki ?nosi ?llados): lit. National Union of Greece, a fascist nationalist organization, founded in 1929 by George Kosmidis. It had about 2000 members, of whom the majority was immigrants. (Source: J. Hondros, Occupation and Resistance: the Greek Agony, New York, 1983.)

10 Metaxas, Ioannis (1871-1941): Greek General and Prime Minister of Greece from 1936 until his death. A staunch monarchist, he supported Constantine I and opposed Greek entry into WWI. Metaxas left Greece with the king, neither returning until 1920.

When the monarchy was displaced in 1922, Metaxas moved into politics and founded the Party of Free Opinion in 1923. After a disputed plebiscite George II, son of Constantine I, returned to take the throne in 1935.

The elections of 1936 produced a deadlock between Panagis Tsaldaris and Themistoklis Sophoulis. The political situation was further polarized by the gains made by the Communist Party of Greece (KKE). Disliking the Communists and fearing a coup, George II appointed Metaxas, then minister of war, to be interim prime minister.

Widespread industrial unrest in May allowed Metaxas to declare a state of emergency. He suspended the parliament indefinitely and annulled various articles of the constitution. By 4th August 1936, Metaxas was effectively dictator. Patterning his regime on other authoritarian European governments (most notably Mussolini's fascist regime), Metaxas banned political parties, arrested his opponents, criminalized strikes and introduced widespread censorship of the media. But he did not have great popular support or a strong ideology.

The Metaxas government sought to pacify the working classes by raising wages, regulating hours and trying to improve working conditions. For rural areas agricultural prices were raised and farm debts were taken on by the government. Despite these efforts the Greek people generally moved towards the political left, but without actively opposing Metaxas.

11 E.O.N.: National Youth Organization, founded by Metaxas

12 Monastir Synagogue [Monastirioton in Greek]: founded in 1923 by the Aruesti family who had sought shelter in the Jewish Community of Thessalonica - along with other families from Monastir - during the Balkan Wars (1912-1913).

13 Lamia: a city in the mainland of Greece; most Jewish males from Thessalonica were sent to Lamia and its surroundings to forced labor camps during WWII.

14 Thessalonica Ghettos: The two ghettos in Thessalonica were established by the Germans in Fleming and Syngrou Streets, in the east and the west of the city respectively. These were formerly neighborhoods with a dense, yet not exclusively Jewish population. There was no ghetto in the city before it was occupied by the Germans. (Source: Mark Mazower, Inside Hitler's Greece : the Experience of Occupation, 1941-44, New Haven and London)

15 Civil Guard: a.k.a. 'Capo'; young men recruited from within the Jewish Community. (Source: Mark Mazower, Inside Hitler's Greece : the Experience of Occupation, 1941-44, New Haven and London)

16 Joint (American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee): The Joint was formed in 1914 with the fusion of three American Jewish committees of assistance, which were alarmed by the suffering of Jews during WWI. In late 1944, the Joint entered Europe's liberated areas and organized a massive relief operation.

It provided food for Jewish survivors all over Europe, it supplied clothing, books and school supplies for children. It supported cultural amenities and brought religious supplies for the Jewish communities. The Joint also operated DP camps, in which it organized retraining programs to help people learn trades that would enable them to earn a living, while its cultural and religious activities helped re- establish Jewish life.

The Joint was also closely involved in helping Jews to emigrate from Europe and from Muslim countries. The Joint was expelled from East Central Europe for decades during the Cold War and it has only come back to many of these countries after the fall of communism. Today the Joint provides social welfare programs for elderly Holocaust survivors and encourages Jewish renewal and communal development.

17 NLF: National Liberation Front - Ethniko Apeleutherotiko Metwpo (EAM), founded at the end of 1942. It was the combating section of the left-wing Resistance. (Source: J. Hondros, Occupation and Resistance: the Greek Agony, New York, 1983.)

18 ELAS: Ethnikos Laikos Apeleutherotikos Stratos - National Popular Liberation Army, the central organization of the left-wing Resistance, joined also by other pro-democratic individuals. (Source: J. Hondros, Occupation and Resistance: the Greek Agony, New York, 1983.)

19 WIZO: Women's International Zionist Organization; a hundred year old organization with humanitarian purposes aiming at supporting Jewish women all over the world in the field of education, economics, science and culture. The history of WIZO in Greece began in 1934 with a small group of women, which was inactive throughout WWII.

In 1945 WIZO was again active in Greece because of the efforts of its first president, Victorine Kamhi, who eventually moved to Israel. After her retirement she was named an Honorary Member of WIZO. (Information for this entry culled from http://www.movinghere.org.uk/stories/story221/story221.htm? identifier= stories/story221/story221.htm&ProjectNo=14 and other sources).