Lev Dubinski

Interviewer: Roman Lenchovski

Date of interview: October 2002

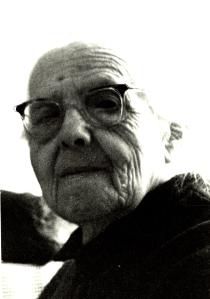

Lev Dubinski lives in a three-room apartment in a solid brick house in Industrialnaya Street at some distance from the center of town. His wife Elena received this apartment back in 1961. Lev and his wife Elena Shepenkova, their daughters Irina and Lilia and Lev’s parents Peisach and Maria used to live in this apartment at the beginning. Now his younger daughter Lilia and her husband Yuri Maltzev live with Lev. We had our discussion in Lev’s room, full of books. There are technical books as well as Russian, Ukrainian, Jewish and German classics. We sit at the round table where Lev’s family used to get together before the war. Lev is a slim gray-haired man of average height with a friendly face. He has deep shrewd eyes and clear logical manner of speaking. When we talked about his grandfathers and great grandfather, his aunts and uncles his memory failed him at times and his voice quivered. There were tears in his eyes…Lev was an expert in the energy field. He is a veteran of the war. He is depressed about the uncertainty of the future.

My memory goes as far as to my great-grandfather in the history of my family. I don’t know his name since my father always called him ‘grandfather’. He was born in a small Jewish town [shtethl] in Kiev province in 1840s. Then he lived in Taborov town near Belaya Tserkov in Kiev Province, where he was Assistant Manager at the countess Branitskaya’s estate. There was Ukrainian, Russian and Jewish population in Taborov. Jews constituted about one third of the population. They dealt in trade and crafts. My great grandfather told us that at his time there were few synagogues, cheder and Jewish hospital in Taborov. Yiddish and Ukrainian were equally spoken in the town. My grandfather Srul Simcha Dubinski was born in Taborov in 1870. He got married at the age of 18. His wife Sarra (I don’t know her maiden name) was younger than he. She must have also come from Taborov. I am sure they had a Jewish wedding with a chuppah and a rabbi. It couldn’t have been otherwise at that time. They spoke Yiddish in the family, observed Jewish traditions and went to synagogue. Grandmother Sarra was a housewife. In 1889 their first baby Iosif was born. Two years later Revekka was born. Then came my father Peisach in 1893, in 1896 Lev was born and in 1898 — Mark. Isaac was born in 1906 and in 1909 — Pinia was born. Grandfather Srul Simcha didn’t have a profession. He may have finished cheder. For some time he was a stableman for a landlord in Skvira, near Belaya Tserkov, but he kept looking for something better in his life. He had to provide better for his family, he thought. He obtained a visa to USA where he moved in 1911 hoping to earn some money and take his family to America. Grandmother Sarra and the children stayed with his father. Great-grandfather kept a tavern in Taborov to support his grandchildren, but the family was poor anyway: children had to share one pair of shoes. My father always admired and loved his grandfather. He thought he was a self-sacrificing man. I remember how our father took my sister and me to the hospital where our great grandfather was in late 1920s. Medical assistants carried him outside in his stretches to say his farewells to us. He died shortly afterward. He was buried in accordance with Jewish traditions at the Jewish cemetery in Taborov.

My father, Peisach Dubinski was born in Taborov in 1893. At the time his father Srul Simcha was a stableman for countess Branitskaya and the family lived near the mansion in the vicinity of Taborov. Although there was a cheder my father went to a parish school [Orthodox Christian school]. The Cheder was located at a long distance from home and for this reason my father’s parents sent him to a parish school. My father said that his schoolmates teased him a lot and it was anti-Semitic attitude. He was the only Jewish boy at school. Ukrainian boys were fair-haired snub-nosed boys while my father had a typical Semitic appearance: brunette with a big nose. Besides, he spoke Ukrainian with a strong Jewish accent that also resulted in a lot of teasing. However, one teacher stood for him. At religion classes the priest held up my father as an example ‘Look, although this is a Jewish boy he knows Christian prayers best of all of you’. My father attended Christian lessons since it was mandatory for all pupils to attend all classes. He knew Christian prayers best among all other pupils. My father studied successfully at school and manager of the estate in Taborov hired him to teach his son. After finishing the parish school where he studied 4 years my father went to work in a hardware store. He told us that he lived in an attic. He was eager to study and read, but he didn’t get a chance to continue his education.

In America my grandfather Srul Simcha worked at a button factory saving money for boat tickets. He sent tickets before the Revolution of 1917 1 and his daughter Revekka came to America. She also worked at the button factory where she joined the Communist Party and became its active member. My father also received a ticket to America. He got as far as Antwerp where for some reason he didn’t get immigrant visa from the commission to move on and he had to go back home.

In 1914 when World War I began my father’s older brother Iosif was recruited to the army. He took part in the war and was captured. At the beginning of World War I the Pale of Settlement 2 was abolished and Jews began moving to bigger towns. The Jewish population in Kiev increased significantly. My great-grandfather Dubinski, grandmother Sarra and her sons also moved to Kiev from Taborov. The family rented an apartment in Basseynaya Street in Kiev. My father and his brothers went to work as shop assistants in an hardware store.

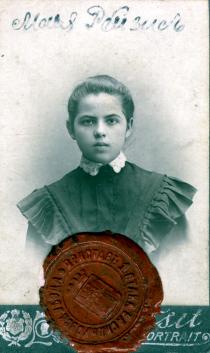

Shortly afterward my father met Maria Reizis, a Jewish girl from Belaya Tserkov. The Reizis family also moved to Kiev after the Pale of Settlement was abolished. They rented an apartment in the center of the town. My parents got married in 1916. They had a Jewish wedding. They installed a chuppah in the yard of the house where Maria lived. The ceremony was conducted by a rabbi from Brodski synagogue [Brodski family] 3. The newly weds settled down in the Maria parents’ apartment on the corner of Prozorovskogo and Saksaganskogo Streets in the center of the town.

My maternal grandfather Meyer Reizis was born in a town near Belaya Tserkov in 1864. He finished cheder, but he didn’t continue his studies. He was smart, though. He worked at a mill sorting out bags with grain and then he became an assistant accountant in an office. His wife Liya was born in a town near Belaya Tserkov in 1867. After the wedding the newly weds moved to Belaya Tserkov. My grandfather earned little for sorting bags and my grandmother kept cows and sold dairies.

My grandfather Meyer had 2 sisters and brothers. I only knew one sister Miriam Reizis, born near Belaya Tserkov in 1860s. She lived in Belaya Tserkov later. She didn’t have any education and was a housewife. Miriam had two daughters: her older daughter Tsypoira was deaf and dumb. I don’t remember her older daughter’s name. They lived in Basseynaya Street in Kiev. Both daughters perished in Babi Yar 4 in 1941. She also had a son named Moisey. He worked as a doctor in Belaya Tserkov. He was much respected. He never refused people and helped them for free whenever they needed him. Miriam died in Belaya Tserkov before the war. Moisey moved to Kiev with his family after the war. He died in 1980s.

They had five children: their oldest daughter Tsypoira was born in late 1880s. She had no education and was a housewife. She had a Jewish husband named Yakov Yezril and two sons. Her older son Michael, born in 1910, had meningitis when a child and was epileptic. He finished a secondary school, but he never went to work due to his health condition. He was very interested in politics: Stalin and other leaders were his idols. When in evacuation during the war he fell ill with tuberculosis and died. The second son – Naum, was born in 1914. He finished Kiev Industrial College and was a radio engineer. In 1941, at the beginning of the war he was in a group of radio operators that received a task to blast a radio station. I don’t know whether they completed their task, but I know that they all perished in a camp for prisoners-of-war near Kiev. Naum’s wife, Sonia Volodarskaya, Jew, was raising their son Mark, born in early 1941. My parents supported Mark and Sonia, particularly, after Tsypoira died in 1953. Mark finished Kiev Polytechnic College. He is an energy engineer. Sonia died in Kiev in late 1980s, and Mark moved to Israel in 1989. We’ve lost contact with him.

After Tsypoira there was Polina, born in 1891. She didn’t have any education. Her father taught her to read and write a little. He also taught Tsypoira. Polina was a housewife. She was short and plain and grandmother always felt sorry for her. Polina was married to a nice and kind Jewish man Lev Zagrebel’ny. He was a prisoner during World War I. When he returned home he wanted to marry Elia, the youngest sister, but grandmother said ‘No, you shall marry Polina I dare to say’. She got a nice dowry and he married Polina. Their son Boris became a design engineer. He worked at a military plant in Moscow and retired in the rank of lieutenant colonel. Lev dealt in commerce. He died in 1947. Polina’s neighbor looked after Polina and Boris sent her money to pay her neighbor for care. My wife and I were working then. We also helped Polina whenever we could. She died in Kiev in early 1980s.

My mother Maria Reizis was born in 1893. My mother was beautiful and smart. She was one of the best pupils in the grammar school in Belaya Tserkov. She finished grammar school with honors. Elia, the youngest sister, was 3 years younger than my mother. She also studied in grammar school, which she didn’t finish. Elia married Lev, my father’s brother. They had a daughter named Mary. She was born in 1923. She graduated from Kiev State University and was a Ukrainian teacher at school. She liked Ukrainian literature and was fond of Ukrainian folk songs. Elia’s son Moisey was born in 1924. He was 17 when the Great Patriotic War 5 began. He went to excavate trenches near Donetsk. He returned home in late September 1941 and went to Babi Yar in Kiev with other Jews.

My grandparents’ youngest son Moisey was born in 1900. He finished cheder and grammar school. My mother told me that he was extremely strong: all other boys in Belaya Tserkov were afraid of him. He was tall, strong, healthy and handsome. He always protected my mother from the young men that were too insistent demanding her attention. When in 1915 the Pale of Settlement was abolished my grandfather Meyer decided to move his family to Kiev. He wanted his son Moisey to get a good education and arrange successful marriages for his daughters. Moisey entered Kiev Medical College. In 1918 he married Lisa Spector, a Jewish girl. A year later their daughter Lusia was born. Moisey sympathized with the Whites 6, but when in 1919 during the Civil War 7 Denikin 8 units came to town his neighbors reported that he was a communist and provided medical care to the Red Army troops. He was a devoted doctor and never refused patients regardless of their political convictions or nationality. They lived in 9, Basseynaya Street. One night Denikin’s soldiers took him away from home. There is a family legend that relatives wanted to give ransom for Moisey. They collected some gold, but when they came to his guards it was already too late. Moisey was gone. Relatives began to search for Moisey, but they failed. Few days later they heard that Denikin troops shot their prisoners at the town cemetery. Grandfather Meyer and my father went there and found Moisey. [his body] They buried him at the Lukianovska Jewish cemetery 9 in accordance with the Jewish tradition. This was a tragic death of a strong 19-year-old man. His daughter was 3 months old when he perished. Lusia died of tuberculosis in 1932 and Lisa perished in Babi Yar in 1941. There was only one photo brooch of Moisey. Grandmother Liya always wore it. She felt guilty that the family came up with their ransom too late.

In Kiev grandfather Meyer opened a store selling construction materials. It was located in the center of the town. Grandmother worked there as a shop assistant. The store was closed at the end of NEP 10 in 1929. My grandparents moved to 21 Malo-Vasilkovskaya Street near the Brodski synagogue. They rented an apartment in a private house. There was a terrace and two connecting rooms in this apartment. They were poor, but their relatives came to celebrate Jewish holidays with them anyway. Their children and their families were not religious and didn’t observe any Jewish traditions in their homes, but they enjoyed visiting their parents on Jewish holidays. My grandfather and grandmother were religious. They went to the Brodski synagogue. My grandfather wore a black yarmulka and had a short gray-haired bear and moustache. He was a slim short man. He wasn’t a pedantic orthodox that follows all rules and rituals, but they always celebrated Sabbath. My grandmother wore a kerchief that was a rule for Jewish women. On Friday my mother’s sisters and their families visited their parents and my grandmother lit candles. My grandparents always celebrated Pesach. I remember one celebration. The table was covered with a snow white tablecloth. There was red wine, fancy wine glasses and food on the table. I was surprised to see wine since we never had strong drinks at home. Grandfather sat at the head of the table with a white cloth with black stripes on him. This was a tallit. He had leather boxes on his forehead and on his hand: tefillin. I also remember Chanukkah: a merry holiday when the whole family got together to celebrate. Grandfather gave his grandchildren Chanukkah gelt. There was a chanukkiah with 7 candles and one in the center. When my mother’s sisters and my father’s brothers got together for a celebration they only spoke Yiddish.

Grandfather spoke Russian to his grandchildren and Yiddish – to grandmother and his children. Our grandmother spoke Ukrainian that she could hardly speak to the grandchildren and Yiddish – to her children and our grandfather. She was a very kind woman, but she had no education whatsoever. However, she loved us dearly and we did love her. I also have happy memories of my grandfather. He loved his grandchildren dearly. He often asked me ‘Who do I love most of all?’ and I replied ‘Me’ and he said ‘That’s right!’ Maria and other children also made a right guess since he really loved all of us a lot. There were many children paying in the yard where my grandparents lived. There was a volleyball grid stretched and Maria and I liked to go and play volleyball with other children.

I was born in Kiev on 7th December 1916. Less than a year later the October revolution took place. My relatives had different reactions to this event. In 1917 Iosif returned from the front and moved to America. In February 1917 my father’s brother Mark joined the Bolshevik Party and took part in the revolution. My mother’s father Meyer Reizis was skeptical about the revolution. As for my father, I remember him saying ‘Of course, there were many bad things, but look how the country changed! Look at the houses! Nobody has to share one pair of boots to go to school! My great grandfather also had a loyal attitude toward the revolution since his family was very poor before the revolution and he could compare things. For some time grandfather Srul Simcha kept in touch: he sent boat tickets for his wife and children and in Revekka returned in 1921 to take her mother and brothers with her. However, my father Peisach and his brother Lev were already married. They stayed here and so did their brother Mark. Grandmother Sarra, Isaac and Pinia moved to America. During NEP they sent us money and we could buy things in Torgsin stores 11. I remember they sent us $10 during Famine in Ukraine 12 in 1930s. This was a big support for us. My grandmother had eye problems in America. Later we lost contact with them. In 1930s correspondence with relatives abroad was forbidden 13. If one only mentioned having relatives in America in application forms it put an end to one’s career.

My father’s brother Lev had no education. After moving to Kiev he worked as a shop assistant in a store. He married my mother’s younger sister Elia Reizis. They lived in Basseynaya Street.

Mark finished the Military Academy in Moscow in the rank of a division commissar. He was a well read and intelligent man. He went into the revolution. After finishing the Academy Mark lived in Kiev. Then his unit was transferred to Borisov in Belarus where he was chief of Harrison. He didn’t make a prompt military career, though. He was an honest and outspoken man. Mark was married, but had no children. His wife was a housewife. In 1937, during Stalin’s purges 14 Mark avoided arrest only by miracle. A colleague of his spoke at one meeting. He said some people fail to be watchful: for example, Mark Dubinski hadn’t determined one single ‘enemy of the people’ 15. Mark came home, packed his bag and sat expecting an arrest, but nothing happened. In the morning it turned out that the man who said this at the meeting was arrested. Mark’s commanding officer sent Mark to a provincial division where he could be safe. When the Great Patriotic War began he was promoted to the rank of senior commissar of a battalion and sent to the front near Yelna in the vicinity of Smolensk. He got wounded in his arm and had to go to hospital. After the hospital he was demobilized. He lived in Moscow and worked as human resource inspector in the Navy Ministry. He had a nice apartment. He was a law obedient communist. I think he understood what was going on, but he believed in the idea, however strange it may seem. He had many doubts at the end of his life. He had some inner fear since 1937. My sister Maria lived in Moscow since 1943. Mark was very attached to her. He treated her like a daughter. She said that at the end of his life Mark had persecution mania that made life unbearable. She couldn’t open the door to a postman, call a doctor or let a medical nurse in. He went to distant bakeries to buy bread so that shop assistants didn’t remember him. He had never had anti-Soviet spirits, but there was some bitterness that he suffered from. He came to see Maria to warm up a little. He brought presents for her children. When Mark was a widower Maria asked whether he could obtain a permit for one of her sons to reside in his apartment so that after he died the apartment could belong to her children, but he refused explaining that he couldn’t reveal any documents to keep safe. This was evident persecution mania. Mark died in Moscow in 1985. He was buried at the town cemetery and his apartment went to some outsiders.

I went to synagogue with my [maternal] grandfather carrying his prayer book I was a cute boy: I had golden curls and was called ‘a little lord’ in my childhood. I remember that when in 1930s Soviet authorities began their struggle against religion 16 they closed Christian, Catholic and Jewish religious institutions. The Brodski synagogue was closed in 1931 our grandfather called Maria and me to help load the Torah scrolls on a truck. I don’t know where they hauled all these valuables. Shortly afterward our grandfather fell ill. He had to stay in bed and our mother went to look after him. He died of lung cancer in 1934. He was buried near Moisey’s grave at the town cemetery in accordance with the Jewish tradition. When grandfather died my grandmother and my mother’s sister Tsypoira sat on the floor for 7 days. My mother told me it was a requirement of the Jewish procedures.

My parents were raised in religious families, but they were not religious themselves. They thought there was too much suffering in life and if God existed he wouldn’t allow things to happen. They attended synagogue when they were children, but, as my father and mother stated it was a ‘childish faith’.

We lived in a 4-storied house on the corner of Prozorovskaya and Saksaganskogo Streets in the very center of the city. There were Jewish, Ukrainian, Russian and Polish tenants. My parents were always busy and I spent much time outside playing with other children. We didn’t care about nationality. My parents spoke Yiddish at home, particularly, when they were arguing and didn’t want us to understand the subject of their discussion. They spoke Russian to Maria and me. I could understand Yiddish well, but I could hardly speak any. My parents tried to teach me to read in Yiddish, but I was an impatient pupil and didn’t learn much. My parents spoke Yiddish until the end of their days. My father and mother read many Russian books: they were particularly fond of Russian classics Gorky 17 and Gogol 18. They spoke fluent Russian.

My father was an assistant accountant in a trade association. My mother was a housewife. She spent a lot of her time in the kitchen and I heard her singing there. She sang Soviet popular songs, but I don’t remember her singing Jewish songs.

We had very close relationships with my mother’s sisters and their families. They didn’t observe any Jewish traditions. Perhaps, they had faith inside, but they were far from orthodox beliefs. [Editor’s note: probably practices] Besides, in 1920s the Soviet regime struggled against religion. My parents didn’t observe Jewish traditions. I remember my mother eating brown bread at Pesach – she liked it. She always asked Maria and me ‘Please, don’t tell your grandmother or grandfather that I’ve eaten brown bread’. And we kept it a secret. My father liked pork fat and cracklings very much. His breakfast consisted of brown bread with cracklings that he liked through his life. This is the way I remember my parents, but I don’t know whether they had different habits before.

I liked meeting with my cousins Michael, Naum, Boris and Moisey, but I spent most of the time with my friends in the street. On 1st May 1923 my sister Maria was born. She was the first baby in our family, born after my mother’s brother Moisey perished and was named after him: the first letter in her name was the same as in Moisey’s name. I remember that my mother was feeling ill and my father took Maria after he came from work and sang songs in Yiddish carrying her around our roundtable covered with a nice tablecloth. My childhood memories come back to me whenever I hear Jewish tunes.

In 1924 I went to the first grade at Russian school # 33 in Gorky Street near our house. We had a wonderful teacher. Her name was Nina Badibelova, a very intelligent lady. Her father was a general. She loved children. She was strict with us, but fair and we loved her in return. She read poems by Pushkin 19 and Shevchenko 20 in Russian to us. After I finished the 4th grade our school was turned into a Jewish school. All it meant was that the language of teaching changed to Yiddish. Everything else was the same. I really had a poor conduct of Yiddish and I went to study in Russian school # 53. I wish I knew Yiddish and Ivrit. My parents decided that I had to go to a Russian school. They thought that one had to follow the rules of the country one lived in. I also understood that I had to learn Russian. My school was a grammar school for girls before the revolution. It was located in Fundukleyevskaya Street. We had very good teachers that used to teach in the former grammar school. Maxim Tkach was a wonderful teacher of Ukrainian. I began to read Ukrainian books then. At that time I began studying Ukrainian culture. I liked literature and was fond of reading, but I didn’t choose it for profession. I read everything that fell upon me. Later I became fond of Dostoyevskiy 21. I also read Sholem Alechem 22 and other Jewish authors in Russian. I read Ukrainian authors: Shevchenko 23 and Lesia Ukrainka 24. I was growing up in the Russian culture and I do not have any preferences based on national origins. I identified myself as a Jew and I knew that my parents were Jews, that their mother tongue was Yiddish and that grandfather went to synagogue, but it had no effect on me.

I studied well and was a leader at school and in my street. My friends respected me and listened to my opinions. I didn’t face any anti-Semitism. I became a pioneer at school. We wore red neckties and sang ‘Rise in flames, blue nights…’ – a hymn of pioneers. We also competed in our studies. In 1931, at the age of 14 I finished lower secondary school and submitted my application to the Electrotechnical College. I wasn’t even allowed to take exams since my father was a clerk and there was a quota based on one’s origin in higher educational institutions. Then I passed tests at the employment agency that gave me a letter of recommendation to go to a factory vocational school. There were children of white-collar workers studying there after they failed to enter higher educational institutions. There were also children of workers, of course. There was a rather high level of education and many of my contemporaries made good careers in future. This school gave secondary education and a profession. After two years of studies I got a profession of 3-grade electrician. There was a 7-grade category for this profession and my grade was good for me considering that I was only a 16-year-old teenager. This qualification enabled me to work as a general electrician on any enterprise, unless it came to some specific situations that required higher qualifications.

I remember the period of famine in 1933. We didn’t quite suffer from hunger since there were better food supplies in big towns. Our neighbor Kuznitcinskiy that had a wife and two daughters brought his son from his first marriage. Their boy was swollen from hunger. The boy’s stepmother didn’t quite like him, but they rescued him from death anyway. I also saw a woman in the street dying from starvation. The famine was explained by the fact that ‘enemies of the people’ were hiding bread and there was not enough of it, therefore. I didn’t really believe it. Nowadays some TV channels, radio stations and newspapers state that it was an intended extermination of the Ukrainian people. I think that it was just ruthless policy of collectivization 25. They took away everything from villagers leaving them to starve to death. The motto was – who is not with us is against us. They showed no mercy to people exterminating them.

After finishing my school I went to work as an electrician at the cashier manufacture plant and went to study in the evening department of Rabfak 26 to complete my secondary education. I met Elena Shepenkova, a Russian girl, at the rabfak. Elena lost her mother at the age of 3 and was raised by her father Iosif Shepenkov. Maria told me later that my mother wasn’t quite happy that I was seeing a Russian girl, but she did not mentioned it to me. She only said at the beginning ‘She is an orphan. If you are not serious about it – just leave her alone’. I was serious about her. ‘

In 1934 I passed my entrance exams to Kiev Industrial College with all excellent marks, but was not admitted. Their official response was ‘there are no vacancies’. The admission commission said I had to gain work experience since one year that I had was not enough. This was unfair: there were other students that passed their exams with worse marks, but were admitted. This was social injustice again, but what could I do? I returned to my rabfak school where I studied for another year and worked as a junior radio engineer at the RV-9 radio station. There was a nice work team there: engineer on duty was a Jew, chief engineer was Russian and technicians: Russian, Ukrainian, Polish and even a Tatar men. This radio station broadcast all over Ukraine. I was gaining life and work experience. A year later, in 1935 I took exams at the Industrial College again. I didn’t pass my exams as successfully as a year before, but I was admitted to the Electric Engineering Faculty. I studied in College and worked at the radio station for another half year. There was a coupon system. All employees received food coupons. So did I. A coupon was worth 600 rubles per month that was a lot of money (more than a stipend). I worked night shifts, but my friends let me sleep a little to be fit for studies. Half a year later I quit. I understood it was too hard to work night shifts and study.

1937, a year of Stalin’s purges, began [Great Terror]. Director of our college Efimov, a nice man that always supported students and worked out improvements of the studying processes disappeared one day. We were told that he was an ‘enemy of the people’. I said to my friend ‘Kolia, he does not seem to be an ‘enemy of the people’. He replied ‘What do we know anyway? I don’t think he is an enemy, but who knows? Let us not discuss this subject’. We understood that it was dangerous to discuss certain subjects. There were general meetings condemning people. Secretary of the Faculty stood up, made a speech and said ‘there is a proposal to condemn this person and issue the following resolution’. Then the resolution was pronounced and all attendants expressed their approval by raising hands. For some people it was just a matter of making a career and others were indifferent. Only brave people having their own principles dared to speak against a crowd. We were conformists. If someone decided to go against a common line one had to be prepared for oppressions. For us it might mean expel from College or even arrest. We didn’t have a right to have our own opinions. There was one chief and one single point of view: everything he said was to be followed.

I joined Komsomol 27 after a while. I wasn’t a big politician, but I already had my doubts about the situation in the country. Almost all of my co-students were Komsomol members. Only those that didn’t study well were not admitted. In 1939, when I was 23, a secretary of our Komsomol unit asked me ‘What is it all about? Why aren’t you joining Komsomol?’ I replied ‘My studies take all of my time. Besides, I am not ready from a political point of view’. He said ‘Stop it. If you have specific reasons let’s talk about them’. I had relatives abroad and it was very dangerous. We were not in touch, but I kept this fact a secret. One of my co-students was expelled for reading books by Trotsky 28 that was put of favor at the time. It took us quite an effort to stand for him since he was about to be expelled from College. I decided to stop being a black sheep and joined Komsomol in 1939. I attended meetings to keep up with the crowd and paid my monthly fees on time. At some meetings they discussed students that had to improve their studies, but there were hardly any political subjects on the agenda.

After finishing the Rabfak school, Elena entered the Faculty of Chemical Equipment Manufacture at the Industrial College. We got married in 1939 and lived with my parents. They partitioned half of their room for us. A year after Elena finished the College and got a job assignment 29 to Tuapse in the Caucasus [in Russia]. She was on the family way then. I was assigned to a military training in College that extended my studies in College for half a year. We wrote a letter to the plant in Tuapse where she was to be employed requesting them to release her due to her ‘condition’. They gave us their consent and Elena received a ‘free’ diploma.

I finished College in March 1941 and got a diploma of power engineer. I went to work as an engineer to the power plant in Kiev regenerator rubber plant in Darnitsa on the left bank of the Dnieper. On 18th May 1941, a month before the Great Patriotic War our older daughter Irina was born. In June 1941 my sister Maria finished school and entered the Music Pedagogic Department in Kiev Conservatory. She had a prom on 22nd June and at 4 a.m. in the morning Kiev was bombed. The war began. My plant was getting ready for evacuation. Our management left for Kharkov before everybody else. I received a subpoena to the military registry office and mobilized on 7th July. I was included in the team of 12 experts with higher electric engineering education to study at the Faculty of Special Equipment in the Leningrad Air Force Academy named after Voroshylov. When we arrived in Leningrad the Military Academy had evacuated to Yoshkar Ola in Central Asia [today Russia in 3200 km from Kiev]. We were lucky to be late since pilots that entered the Academy in 1941 perished in their first battles. They didn’t have sufficient training and flew planes that couldn’t compete with German planes. Our team took training in the flak school in Leningrad. After finishing this school in October 1941 we were sent to the flak battery in Didkovo village near Moscow. We were in the flak defense of Moscow. I was an artillery man all through the war. Artillery units were in few kilometers from the front line at the distance of a cannon shell flight from the front line. On 7 July 1941 my wife and our baby evacuated on a boat-pulled barge. Elena evacuated with her aunt that worked at the Bolshevik plant. They reached Dnepropetrovsk and from there they traveled to Sukhoy Log, Sverdlovsk region by coal transportation trains.

My father was 48 years old in 1941. He was also mobilized: in early July was sent to labor units in Donetsk. From there authorities sent them back home. My mother and sister were not planning to evacuate. They didn’t think the war was going to last long and they believed that Germans were civilized people. Maria was demobilized to excavate trenches, but mother kept her at home. Elena’s father Iosif Shepenkov was chief accountant in Kiev Sugar Trust. He helped my mother, Maria, Elia and Mary to evacuate with his company. They reached Kursk [about 400 km from Moscow] where Maria entered a Pedagogic College. However, they had to move on since the front line was coming near the town. My father returned to Kiev in early September and Iosif helped him to evacuate as well. Iosif decided to stay in Kiev: he had trombophlebitis and it was hard for him to move. My father reached Kursk and they headed for Kuibyshev [today Samara in Russia, 1000 km from Moscow ] in Central Asia where they got a letter from Elena. She wrote she was waiting for them in Sukhoy Log village [2300 km from Kiev]. Before we parted we agreed to write post restante to bigger regional towns. When they met with Elena my mother stayed with our little daughter at home and Elena went to work as chief mechanic at the Salvageable non-Ferrous Metal Plant. My father was a storage keeper at this plant. He had a kitchen garden near his storage facility where he grew potatoes. It helped them to survive during the war.

The Kiev Conservatory evacuated to Sukhoy Log and my mother hoped that Maria would study there, but Maria didn’t have an instrument and had to give up music. She went to work in hospital evacuated from Leningrad. She was employed for the position of an attendant, but she was actually an entertainment specialist: she played for patients, but she also looked after them and cut and fetched wood for stoves. In late 1942 the hospital returned to Leningrad. Maria was a civilian and did not go there. In August 1943 Maria came to Moscow. She found me in Did’kovo where our flak battery was deployed and stayed with me 3 days. That year she entered the Faculty of Economics in Moscow State University.

Many military joined the Party at the front. One commander of our regiment said ‘You must submit your application to join the Party’ and I replied ‘I am not worthy to join it yet’. He said ‘Stop chattering like that. You are an officer with a higher education and you spoil this whole picture here. Just write a request’. I had no choice and I submitted my request, but I felt a more decent and honest man when I did not belong to the Party.

In November 1943, as soon as Kiev was liberated I requested a leave and went to Kiev to search for my cousin brother Naum, son of my mother’s sister Tsypoira. I got a drive to the outskirts of Kiev and from there I had to walk since there was no transportation. I walked along the railroad track keeping my hand on my gun: there were numerous bandits on he roads. A patrol officer stopped me to check documents and warned me: ‘When you reach Kreschatik [Kreschatik is the main street of Kiev] walk in the middle of the street beware of bandits and ruins’. Elena’s father Iosif Shepenkov stayed in Kiev. He was a Christian and Germans didn’t touch him. Iosif wrote me that Naum was sent to a concentration camp in Darnitsa. It was the end of November: it was cold and got dark early. It was hard to see Kreschatik in ruins. My wife and I used to enjoy its beauty before the war. I got to the left bank and found ashes at the concentration camp site. I talked with local residents, but found no traces of Naum.

Our neighbors told me that Liya and Elia’s son Moisey perished. When it became clear that Germans were coming to Kiev grandmother, her daughter Tsypoira, her son Michael, her husband Yakov, her daughter-in-law Sonia and her grandson Mark hired a horse-driven wagon and moved to the east. There was also their luggage on the wagon and they had to walk behind the wagon. My grandmother was an old woman and could hardly walk. She said she wanted to go back home. She kind of foresaw her death. She said she wanted to die at home. She got a ride back home. Grandmother Liya came to her apartment in September 1941. When on 29 September all Jews were ordered to go to Babi Yar the janitor woman reported on her. Other neighbors tried to rescue my grandmother pushing her bed behind a wardrobe, but the janitor reported to policemen that there was another Jewish woman in the house. This janitor wanted my grandmother’s room and she got it afterward. At that same time Elia’s 17-year-old son Moisey came to his grandmother from where they were excavating trenches. Policemen dragged my grandmother from the 2nd floor. She was actually paralyzed and when it became clear that she couldn’t march to Babi Yar Germans shot her right near the entrance to the house. Her daughter Tsypoira lived in this house in Malo-Vasilkovskaya Street for a longtime after the war. My grandmother, Moisey and Naum had no graves. There are no traces of them. There is nothing left.

There was a heavy load on my heart when I returned to my unit. Our flak battery was near Moscow until 1944.

In 1944 Elena, our 3-year-old daughter Irina and my parents returned to Kiev from evacuation. There were neighbors residing in our apartment. They didn’t want to move out and Elena, our daughter and my parents had to live with my mother’s sister Elia in Institutskaya Street. There was too little space for all of them. They lived in a garret and there was no gas or toilet there, of course. My mother cooked on a primus stove. Elena told me that every evening she rushed home to make sure that a dry wooden house was still there. Elena went to work as an engineer at ‘Ukrgiprogas’ Institute, my father was a shop assistant in a hardware store and my mother was a housewife.

After the war with Germany was over in spring 1944 our artillery units was sent to the Far East to fight against Japan 30. I shall not speak about the war with Germany or Japan. Those memories are too hard to bear. Our military drank a lot on the Japanese front – probably because they were too bored. They were looking for hard drinks. Once they got some wood alcohol and I remember a young lieutenant that kept asking ‘Will I get blind from drinking this?’ He did. When the war with Japan was over our officers had bags and trains loaded with what they looted. I felt angry about it. My wife was always proud that I never got involved in it. I bought a piece of Japanese silk for her and this was all I brought. I finished the war in the rank of captain. I was awarded medals for the victory over Germany and Japan.

In 1946 when the war with Japan was over I returned to Kiev. I had to apply to court to have our apartment back. The court refused us since there were no archives left after the war and there was no solid evidence that the apartment belonged to us. We needed witnesses to confirm that we had lodged there and that my parents were a husband and wife since there was no marriage certificate left. Where could we find a witness to prove that they got married in 1915? Elena’s father Iosif and her stepmother were our witnesses. Iosif to joke afterward: Well, I am like their best friend – I was at their wedding’, but of course, our parents were not even acquainted at that time. I got a good job of personal assistant to the Minister of Transport. I got a letter of recommendation at work that I was told to take to Rudenko [General Prosecutor of the USSR]. I took all documents from the court, including a letter from my work and a letter of solicitation signed by Maxim Rylskiy 31, a well-known Ukrainian poet that was a deputy at that time to Moscow. I had to wait for my appointment for 3 days. The Prosecutor was an overpowering man. He was sitting at his desk in a long office and when I entered the office I heard him saying ‘Well, and how is the captain doing?’ I was wearing my military uniform. I said ‘The captain cannot accommodate his family in our own apartment’. – ‘How come?’ – ‘Occupied’. - ‘By whom?’ – ‘Neighbors’. - ‘Do you mean to say that a combat officer that came from the war cannot accommodate his family in a normal apartment? Give me your papers and come back tomorrow’. He reviewed all papers carefully. When I came a day later his secretary had all my papers with his resolution. This was how I got back my apartment.

On 28 December 1947 our younger daughter Lilia was born. Lilia identified herself as a Jew since she was a child. When she grew up she told us the following story. When she was in the first grade their teacher had to fill up a form and began to ask children their nationality. When it was my daughter’s turn the teacher asked ‘Lilia, and how about you?’ Then she continued ‘Well, you are Russian’, but Lilia corrected her with her voice trembling: ‘No, I am a Jew’. Some of her classmates giggled. During a break Abrasha, a Jewish boy, pointed his finger at Lilia saying ‘Did you hear this? Did you? She is a Jew!’ and another Jewish boy Garik Bresler protected Lilia saying ‘Go away, you fool!’ and Lilia kept saying ‘Yes, I am a Jew!’ Although we never discussed this subject in the family, she understood that Jews needed protection. Probably, the Yiddish language her grandmother and grandfather spoke and the general atmosphere in the house had their influence on the child’s mind.

Lilia liked going to parades when she was small. She went with Elena or me on 1 May or 7 November 32. In 1950s going to parades was mandatory. My colleagues carried Lilia on their shoulders and gave her candy and balloons. There was dancing and singing around and she enjoyed it a lot.

Anti-Jewish state campaigns [Campaign against cosmopolitans] 33 of late 1940s - early 1950s had no impact on us. Of course, those newspaper publications about ‘rootless’ cosmopolites’ or ‘murderers in white robes’ during the period of the doctors’ plot 34 in 1953 were disgusting. All people having sound mind understood that it was nonsense, but they kept quiet. They were scared remembering 1937 when people were removed for saying one hasty word. When Stalin died in 1953 it became easier to breath, though there was confusion in the first moments: aren’t things turning to worse? There were ‘local performers’ that inspired fear in people even at the time when Stalin was an unquestionable authority.

My sister Maria finished Moscow State University in 1949 and was planning to go back to Kiev. When she was a student she met with a Spanish student Anastacio Mancilia-Cruis. Maria lied to Anastacio that she was going to get married in Kiev. He took her to her train, but when she arrived home there was a telegram waiting for her. It said ‘Don’t do anything’. He came to Kiev with the next train and came to our house wearing boots, jacket and worn trousers: this was all he had. Our mother was ill and could not be bothered with Anastacio’s non-Jewish origin. My father said to my mother ‘Maria, the girl loves him!’ They bought Anastacio a new suit and he married my sister. They had a civil ceremony in a registry office. He always had warm relationships with our parents.

Maria’s husband Spaniard Anastacio Mancilia-Cruis was born in Viscaria province in Spain in 1924. His father, a Basque, was a miner and his mother was a housewife both of they Spaniards. There were six children in the family. His father was a socialist and his mother was a communist. When the war in Spain 35 began in 1936 Anastacio and other Spanish children were taken to the USSR. They lived in a children’s home in Yevpatoria. When the Great Patriotic War began this children’s house evacuated to Saratov [in over 1 thousand km from Kiev]. Anastacio studied successfully in a Rabfak and worked and for his successes he got a stipend in Saratov University. The war was over. He finished his first year on the Faculty of Economics when the dean of the faculty told him to continue his studies in Moscow. He arrived in Moscow in 1944 and met Maria. They got married in 1949. In 1950 their older son Thomas was born. They often came to visit us in Kiev. Anastacio graduated from the University and took up postgraduate studies. After finishing his studies he was a lecturer in higher educational institutions in Moscow. In 1962 they moved to Cuba and lived in Havana for 3 years. Maria taught Russian in the Academy of the Russian language and Anastacio – political economy in Havana University. Anastacio was a convinced communist: honest and bright. After they returned from Cuba he worked at the Institute of Social Sciences where he was Professor of Economics and Doctor of Sciences. His father died in Spain in 1949 and his mother was sentenced to 19 years of imprisonment as a communist. In 1957 she was released from prison and died shortly afterward. Two days before she died Maria gave birth to Vladimir, their second son. My sister worked as an editor in business publications. Since 1968 she has been editor of the ‘Issues of Economics’, a journal in Moscow. Her husband Anastacio died in Moscow in 1987.

Thomas finished Moscow Medical College. In 1985 he moved to Madrid. He works as anesthesiologist in a military hospital there. His wife Margarita Hones-Bruno is Spanish. Their daughters Laura and Margarita can hardly speak any Russian. They identify themselves as Spaniards and do not remember any Jewish roots. Maria’s younger son Vladimir was a biologist. He drew very well. His wife was an art expert. He also knew history of arts very well. Vladimir died of sarcoma in 1996, at the age of 39. His older son Alexandr lives in Strasburg. He is a philologist and sociologist. His younger son Piotr works at a TV channel in Moscow.

In 1970 we all of a sudden found my father’ sister Revekka. She was about 80 years old. She lived with her son John Ravinski, his wife, their grandson and great-granddaughter. Revekka and her son were communists. He was against the war in Vietnam and emigrated to Moscow from America under the name of Stanley Bender. Revekka got in touch with my father and I arranged a business trip to Moscow where I went with my father. We met secretly with Mark, Maria and Lilia that studied in Moscow. Since I never mentioned any relatives living abroad they couldn’t pop up as if from nowhere. Even in 1970 this line item about relatives abroad was quite ominous. Revekka and my father spoke Yiddish. Our father translated it for us. John had a good conduct of English. [John grew up in the USA] In Moscow he worked for the ‘Progress’ publishing house. He translated Marx and Engels. They lived in the Soviet Union for about a year, but they didn’t like it here and moved to China. From there they moved to Cuba and then to Chile. John fought with Salvador Allende 36, and was executed with him in 1973. Revekka died from sorrow in 1974. She was buried in Santiago de Chile.

In 1961 my wife received a 3-room apartment in Industrialnaya Street from design institute ‘Ukrgiprogas’ where she was working. It was far from the center, but we were happy that Elena and I, my parents and the girls had their own rooms. In 1966 Lilia finished a secondary school and tried to enter the State University in Kiev, but failed. She worked at a plant for 2 years. In 1968 Lilia entered the College of Economic Statistics in Moscow. She lived with Maria’s family. In 1973 after finishing the college she returned to Kiev and got married shortly afterward. Her husband Yuri Maltzev was Russian and came from Siberia. In 1975 their son Michael was born. In 1977 Lilia and Michael moved in with Yuri. There was too little space and every now and then they came to stay with us. Lilia has worked as an economist: she started at a plant, then worked in the State Computer Center and now she works for a private company. Irina, the older daughter, has lived in Kiev. After finishing school she entered Kiev Polytechnic College. She finished it in 1957 and became a programmer engineer. At first she worked at the programming bureau in the Antonov plant and then went to work at the Autotrans computer center. Irina married Anatoli Gordienko, a Ukrainian man. In 1965 their daughter Anna was born. She finished the Public Economy College in Kiev. She is an accountant there. Her daughter Elena was born in 1990.

Since 1953 I worked in design institute ‘Energoset’project’. I was chief of high-voltage power line design department. In 1970s my nationality issue had an impact on my career. There was a vacancy of chief engineer in my institute. I was an incumbent for this position, but the district Party committee did not approve me for this position due to my Jewish identity. Chief of department was the highest position for a Jew. A Jew could not become director or chief engineer – such was the state policy. However, my wife and I had a good life. We earned well. We went to the cinema and theater and spent our summer vacations at the seashore. We didn’t celebrate any holidays specifically, but we liked to invite friends for a party on Soviet holidays and birthdays and we also visited our friends. Occasionally we went to the theater or cinema, or went for a walk on weekends, but most often we stayed at home enjoying quiet family reunions. We usually spent vacations in the Crimea or Caucasus where we went with the family.

My friends were trying to convince me to move to Israel in 1970s. My argumentation to them was that I had a Russian wife and half-Russian daughters. I also told them that I didn’t know the language. I had a good job here and a good family and I thought that my place was here. My daughters and grandchildren say now that they wish we moved. In 1984 I retired, but at times I worked at Energoset’project under an employment agreement before 1993. My mother lived with sound mind until the age of almost 90. She was the head of the household until the end of her life. She died in 1983 and my father died in 1987. They were buried at the Jewish corner of the town cemetery.

Perestroika 37 began in the middle of 1980s opening our eyes to the crimes of the Soviet regime. I subscribed to a number of newspapers and magazines: we got an opportunity to read everything that had been forbidden before. Many people lost their remaining faith in the Soviet regime. However, this doesn’t mean that everything was bad about socialism. There was stability and social protection. We lost our savings and became poor in an instant. We lost certainty about our future and the future for our children.

In 1990 Elena died at the age of 75. We lived together for 51 years. We celebrated our golden wedding. I was a lucky man: I had a good wife, good family and interesting work. Regretfully, the end of my life is sad. I am limited in my interests. I do not subscribe to newspapers and I don’t go to the cinema: I can’t afford it. I am careful about my old TV set that I bought in 1970s: if something goes wrong I won’t be able to have it repaired. It is depressing to think about what tomorrow has in stock for me. Life becomes more expensive: the apartment fee is 1.5 times higher than it used to be. I receive a small pension. My daughters offer their support, but this alienates us to some extent. They know I don’t like it when they offer their help and they can feel it. My health condition leaves much to be desired: I have hypertension and ischemic disease of the heart. I need expensive medications, but I can’t afford to buy them. There is a privilege for veterans of the war to receive free medications, but in the recent years I’ve only received them twice. Since 1984 I stayed in the military hospital only once. Social insurance agency arranged a course of recreation and I went to a recreation center once. There is a governmental order that veterans of the war can go to recreation centers once a year for free and if they choose not to they can have monetary reimbursement, but the insurance agency explained to me that they receive smaller allowances with every passing year. They don’t have any reimbursement money and they don't have a possibility to send me to recreation center. Before the 50th anniversary of victory the veterans’ committee gave me two envelopes to mail greetings to my fellow comrades and a piece of butter for food package. In the past they had a store with lower prices for veterans of the war. Now it is an ordinary store and some prices are even higher than in other shops. People have become more aggressive and less sociable. In the past neighbors were like friends coming to see each other or share little things. Now, every one sticks to his cell caring only about how to survive. Nobody comes to see me and I do not go out. I cannot afford to have guests and, besides, everyone is busy doing their own things. My fellow comrades are gone. There are few of us left, but we hardly ever meet. The only pleasant thing is a nearby library where I go to borrow books.

After my wife, Elena died I live with Elena [grand daughter] and Yuri [son in law]. My daughters are good to me, but they cannot provide any significant support. I pray for them to be able to carry on. I have a sweet great-granddaughter Sasha, Michael’s daughter, born in 1994. We spend much time together taking a walk in the park and playing.

In recent years I’ve received assistance from Hesed: they deliver food packages to old people and sometimes they provide medications for free. There is also a recreation center where we can stay. I am glad they care about us, old Jewish people. I celebrate birthdays of my close people and a calendar New Year. I haven’t turned to observing Jewish traditions or celebrating Jewish holidays since it is too late to change habits at my age.

GLOSSARY:

1 Russian Revolution of 1917

Revolution in which the tsarist regime was overthrown in the Russian Empire and, under Lenin, was replaced by the Bolshevik rule. The two phases of the Revolution were: February Revolution, which came about due to food and fuel shortages during WORLD WAR I, and during which the tsar abdicated and a provisional government took over. The second phase took place in the form of a coup led by Lenin in October/November (October Revolution) and saw the seizure of power by the Bolsheviks.2 Jewish Pale of Settlement

certain provinces in the Russian Empire were designated for permanent Jewish residence and the Jewish population (apart from certain privileged families) was only allowed to live in these areas.3 Brodski family – Russian sugar manufacturers

They started sugar manufacturing business in 1840s. Organized the 1st sugar syndicate in Russia in (1887). Sponsored construction of hospitals and asylums in Kiev and other towns in Russia, including the biggest and most beautiful synagogue in Kiev.4 Babi Yar

Babi Yar is the site of the first mass shooting of Jews that was carried out openly by fascists. On 29th and 30th September 1941 33,771 Jews were shot there by a special SS unit and Ukrainian militia men. During the Nazi occupation of Kiev between 1941 and 1943 over a 100,000 people were killed in Babi Yar, most of whom were Jewish. The Germans tried in vain to efface the traces of the mass grave in August 1943 and the Soviet public learnt about mass murder after World War II.5 Great Patriotic War

On 22nd June 1941 at 5 o’clock in the morning Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union without declaring war. This was the beginning of the so-called Great Patriotic War. The German blitzkrieg, known as Operation Barbarossa, nearly succeeded in breaking the Soviet Union in the months that followed. Caught unprepared, the Soviet forces lost whole armies and vast quantities of equipment to the German onslaught in the first weeks of the war. By November 1941 the German army had seized the Ukrainian Republic, besieged Leningrad, the Soviet Union's second largest city, and threatened Moscow itself. The war ended for the Soviet Union on 9th May 1945.6 Whites

Soon after buying peace with Germany, the Soviet state found itself under attack from other quarters. By the spring of 1918, elements dissatisfied with the radical policies of the communists (as the Bolsheviks started calling themselves) established centers of resistance in southern and Siberian Russia. Beginning in April 1918, anticommunist forces, called the Whites and often led by former officers of the tsarist army, began to clash with the Red Army, which Trotsky, named commissar of war in the Soviet government, organized to defend the new state. A civil war to determine the future of Russia had begun.7 Civil War (1918-1920)

The Civil War between the Reds (the Bolsheviks) and the Whites (the anti-Bolsheviks), which broke out in early 1918, ravaged Russia until 1920. The Whites represented all shades of anti-communist groups – Russian army units from World War I, led by anti-Bolshevik officers, by anti-Bolshevik volunteers and some Mensheviks and Social Revolutionaries. Several of their leaders favored setting up a military dictatorship, but few were outspoken tsarists. Atrocities were committed throughout the Civil War by both sides. The Civil War ended with Bolshevik military victory, thanks to the lack of cooperation among the various White commanders and to the reorganization of the Red forces after Trotsky became commissar for war. It was won, however, only at the price of immense sacrifice; by 1920 Russia was ruined and devastated. In 1920 industrial production was reduced to 14% and agriculture to 50% as compared to 1913.8 Denikin, Anton Ivanovich (1872-1947)

White Army general. During the Civil War he fought against the Red Army in the South of Ukraine.9 Lukianovka Jewish cemetery

It was opened on the outskirts of Kiev in the late 1890s and functioned until 1941. Many monuments and tombs were destroyed during the German occupation of the town in 1941-1943. In 1961 the municipal authorities closed the cemetery and Jewish families had to rebury their relatives in the Jewish sections of a new city cemetery within half a year. A TV Center was built on the site of the former Lukianovka cemetery.10 NEP

The so-called New Economic Policy of the Soviet authorities was launched by Lenin in 1921. It meant that private business was allowed on a small scale in order to save the country ruined by the October Revolution and the Civil War. They allowed priority development of private capital and entrepreneurship. The NEP was gradually abandoned in the 1920s with the introduction of the planned economy.11 Torgsin stores

Special retail stores, which were established in larger Russian cities in the 1920s with the purpose of selling goods to foreigners. Torgsins sold commodities that were in short supply for hard currency or exchanged them for gold and jewelry, accepting old coins as well. The real aim of this economic experiment that lasted for two years was to swindle out all gold and valuables from the population for the industrial development of the country.12 Famine in Ukraine

In 1920 a deliberate famine was introduced in the Ukraine causing the death of millions of people. It was arranged in order to suppress those protesting peasants who did not want to join the collective farms. There was another dreadful deliberate famine in 1930-1934 in the Ukraine. The authorities took away the last food products from the peasants. People were dying in the streets, whole villages became deserted. The authorities arranged this specifically to suppress the rebellious peasants who did not want to accept Soviet power and join collective farms.13 Keep in touch with relatives abroad

The authorities could arrest an individual corresponding with his/her relatives abroad and charge him/her with espionage, send them to concentration camp or even sentence them to death.14 Great Terror (1934-1938)

During the Great Terror, or Great Purges, which included the notorious show trials of Stalin's former Bolshevik opponents in 1936-1938 and reached its peak in 1937 and 1938, millions of innocent Soviet citizens were sent off to labor camps or killed in prison. The major targets of the Great Terror were communists. Over half of the people who were arrested were members of the party at the time of their arrest. The armed forces, the Communist Party, and the government in general were purged of all allegedly dissident persons; the victims were generally sentenced to death or to long terms of hard labor. Much of the purge was carried out in secret, and only a few cases were tried in public ‘show trials’. By the time the terror subsided in 1939, Stalin had managed to bring both the party and the public to a state of complete submission to his rule. Soviet society was so atomized and the people so fearful of reprisals that mass arrests were no longer necessary. Stalin ruled as absolute dictator of the Soviet Union until his death in March 1953.15 ‘Enemy of the people’

an official way mass media called political prisoners in the USSR.16 Struggle against religion

The 1930s was a time of anti-religion struggle in the USSR. In those years it was not safe to go to synagogue or to church. Places of worship, statues of saints, etc. were removed; rabbis, Orthodox and Roman Catholic priests disappeared behind KGB walls.17 Gorky, Maxim, real name

Alexei Peshkov (1868-1936): Russian writer, publicist and revolutionary.18 Nikolay GOGOL (1809-52) Great Russian novelist, dramatist, satirist, founder of the so-called critical realism in Russian literature, best known for his novel MERTVYE DUSHI I-II (1842, Dead Souls)

Gogol's prose is characterized by imaginative power and linguistic playfulness. As an exposer of the defects of human character Gogol could be called the Hieronymus Bosch of Russian literature.19 Alexandr PUSHKIN [26 May 1799 - 29 January 1837], Greatest Russian poet, founder of classical Russian poetry

Born June 6, 1799, in Moscow, into a noble family. Took particular pride in his great-grandfather Hannibal, a black general who served Peter the Great. Educated at the Imperial Lyceum at Tsarskoye Selo. Most important works include a verse novel ‘Evgeny Onegin’ (‘Eugene Onegin’), which is considered the first of the great Russian novels (although in verse), as well as verse dramas ‘Boris Godunov’, ‘Poltava’, ‘Mednyi vsadnik’ (‘The Bronze Horseman’), ‘Mozart i Salieri’ (‘Mozart and Salieri’), ‘Kamennyi gost’ (‘The Stone Guest’), ‘Pir vo vremya chumy’ (‘Feast in the Time of the Plague’), poems ‘Ruslan and Ludmila’, ‘Kavkazskii plennik’ (‘The Prisoner of the Caucasus’, ‘Bakhchisaraiskii Fontan’ (‘The Fountain of Bakhchisarai’), ‘Tsygane’ (‘The Gypsies’), novel ‘Kapitanskaya dochka’ (‘The Captain's Daughter’). Killed at the duel, 10 to 50 thousand people came to his funeral.20 Shevchenko T

G. (1814-1861): Ukrainian national poet and painter. His poems are an expression of love of the Ukraine, and sympathy with its people and their hard life. In his poetry Shevchenko stood up against the social and national oppression of his country. His painting initiated realism in Ukrainian art.21 Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821-1881) – Russian novelist, journalist, short-story writer whose psychological penetration into the human soul had a profound influence on the 20th century novel

Dostoevsky's novels have much autobiographical elements, but ultimately they deal with moral and philosophical questions. He presented interacting characters with contrasting views or ideas about freedom of choice, Socialism, atheisms, good and evil, happiness and so forth. Dostoevsky's central obsession was God, whom his characters constantly search through painful errors and humiliations. An epileptic all his life, Dostoevsky died in St. Petersburg on February 9 (New Style), 1881. He was buried in the Aleksandr Nevsky monastery, St. Petersburg. His wife Anna Grigoryevna devoted the rest of her life to cherish the literary heritage of her husband. Dostoevsky's novels anticipated many of the ideas of Nietzsche and Freud. Dostoevsky himself was strongly influenced by such thinkers as Aleksandr Herzen and Vissarion Belinsky. He saw that great art must have liberty to develop on its own terms, but it always deals with central social concerns.22 Sholem Aleichem, real name was Shalom Nohumovich Rabinovich (1859-1916)

Jewish writer. He lived in Russia and moved to the US in 1914. He wrote about the life of Jews in Russia in Yiddish, Hebrew and Russian.23 Shevchenko T

G. (1814-1861): Ukrainian national poet and painter. His poems are an expression of love of the Ukraine, and sympathy with its people and their hard life. In his poetry Shevchenko stood up against the social and national oppression of his country. His painting initiated realism in Ukrainian art.24 Ukrainka, Lesia (1871-1913)

Ukrainian poet and dramatist. Ukrainka spent most of her life abroad struggling to recuperate from tuberculosis. Her principal plays, using themes from Western and classical literature, include Cassandra (1908) and In the Desert (1909). The Forest Song (1912) is her dramatic poem based on Slavic mythology.25 Collectivization

In the late 1920s - early 1930s private farms were liquidated and collective farms established by force on a mass scale in the USSR. Many peasants were arrested during this process. As a result of the collectivization, the number of farmers and the amount of agricultural production was greatly reduced and famine struck in the Ukraine, the Northern Caucasus, the Volga and other regions in 1932-33.26 Rabfak

Educational institutions for young people without secondary education, specifically established by the Soviet power.27 Komsomol

Communist youth political organization created in 1918. The task of the Komsomol was to spread of the ideas of communism and involve the worker and peasant youth in building the Soviet Union. The Komsomol also aimed at giving a communist upbringing by involving the worker youth in the political struggle, supplemented by theoretical education. The Komsomol was more popular than the Communist Party because with its aim of education people could accept uninitiated young proletarians, whereas party members had to have at least a minimal political qualification.28 Trotsky, Lev Davidovich (born Bronshtein) (1879-1940)

Russian revolutionary, politician and statesman. Trotsky participated in the social-democratic movement from 1894 and supported the idea of the unification of Bolsheviks and Mensheviks from 1906. In 1905 he developed the idea of the ‘permanent revolution’. He was one of the leaders of the October Revolution and a founder of the Red Army. He widely applied repressive measures to support the discipline and ‘bring everything into revolutionary order’ at the front and the home front. The intense struggle with Stalin for the leadership ended with Trotsky's defeat. In 1924 his views were declared petty-bourgeois deviation. In 1927 he was expelled from the Communist Party, and exiled to Kazakhstan, and in 1929 abroad. He lived in Turkey, Norway and then Mexico. He excoriated Stalin's regime as a bureaucratic degeneration of the proletarian power. He was murdered in Mexico by Stalin’s order.29 Mandatory job assignment in the USSR

Graduates of higher educational institutions had to complete a mandatory 2-year job assignment issued by the institution from which they graduated. After finishing this assignment young people were allowed to get employment at their discretion in any town or organization.30 War with Japan

In 1945 the war in Europe was over, but in the Far East Japan was still fighting against the anti-fascist coalition countries and China. The USSR declared war on Japan on 8 August 1945 and Japan signed the act of capitulation in September 1945.31 Maxim Rylskiy (1895-1964), Ukrainian poet, Academician, Ukrainian Academy of sciences (1943), Academician, USSR Academy of sciences (1958). Was arrested in 1930-31. Lyrical poems, translations, works in literature and folk literature.

32 October Revolution Day: October 25 (according to the old calendar), 1917 went down in history as victory day for the Great October Socialist Revolution in Russia. This day is the most significant date in the history of the USSR. Today the anniversary is celebrated as ‘Day of Accord and Reconciliation’ on November 7.

33 Campaign against ‘cosmopolitans’: The campaign against ‘cosmopolitans’, i.e. Jews, was initiated in articles in the central organs of the Communist Party in 1949. The campaign was directed primarily at the Jewish intelligentsia and it was the first public attack on Soviet Jews as Jews. ‘Cosmopolitans’ writers were accused of hating the Russian people, of supporting Zionism, etc. Many Yiddish writers as well as the leaders of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee were arrested in November 1948 on charges that they maintained ties with Zionism and with American ‘imperialism’. They were executed secretly in 1952. The anti-Semitic Doctors’ Plot was launched in January 1953. A wave of anti-Semitism spread through the USSR. Jews were removed from their positions, and rumors of an imminent mass deportation of Jews to the eastern part of the USSR began to spread. Stalin’s death in March 1953 put an end to the campaign against ‘cosmopolitans’.