Lea Merenyi

Budapest

Hungary

Interviewer: Gabor Gondos

Date of interview: December 2004

Lea Merenyi is a very kind, determined lady. We talked in her apartment in the 6th district, which is a ‘comfortable, small single apartment,’ as she called it. Lea characterized her life saying it was filled with dance and teaching completely, that she has been ‘an apolitical creature all her life.’ In her youth, which she spent in Germany until the age of 18, her parents protected her from finding out what was going on around them. Her family converted, they didn’t even tell the children that they were Jewish. She first started to seriously think about her origins in the car in which she was deported. She subsequently interprets history, which also swept her along a little bit, by reading books.

I was born in Budapest in 1914, but when I was about one or two years old we moved to Hanover [today Germany]. Then, in 1932-34, the family moved back to Hungary. So I don’t know very many things that I should know about the family. The fact itself that we moved away gave me a whole lot to think about, not to mention the fact that I had to learn the language. My parents’ mother tongue was Hungarian, ours was German. I still consider both languages my mother tongue.

I can’t tell you any details about my father’s parents. I knew my grandmother better because we came to visit her several times in Budapest from Hanover. Because they lived here in Budapest. I barely knew my paternal grandfather, I only saw him once, then he died. I only remember his last name: it was Schuller. He had some kind of intellectual occupation, but I don’t remember how he made a living. I know that he had a job. My grandfather must have been an exceptionally inquiring man, but he didn’t care about one thing: children.

I met my grandmother several times. Aunt Roza had an apartment somewhere on Bulcsu Street. [Editor’s note: In Hungary all older women (relatives or acquaintances) are referred to as ‘neni’ or ‘Aunt.’] It was a quite dark apartment, as far as I remember. She was a housewife; women at that time didn’t work. I knew her, she cooked very well, I remember that. I can still see how she decorated the sugar-glazed cake with sour cherries. Once when I was a teenager she took me to the synagogue, so that I would see it. But they didn’t observe religion. I don’t know whether I knew about my origins at that time already or not. I couldn’t find out from the family because this wasn’t a topic, it wasn’t interesting. I’m sure that Aunt Roza didn’t live to see the Holocaust, but I don’t know where she was buried. We never went to the cemetery, partly because we were raised in Germany, and didn’t really keep in touch with the relatives from here.

As far as I know Grandmother Schuller didn’t have any brothers or sisters. There was a distant relative here, who was a very nice woman and she took care of her, but I don’t know how they were related. She took me here and there as a friend, she showed me the City Park. I don’t know whether Grandfather Schuller had any siblings.

My maternal grandparents lived in Germany. The town still exists, it even grew bigger, it’s called Wuppertal-Barmen. There is a river which runs parallel to the Rhine. It’s called Wupper, and the town was on its two banks, by now it’s a very big town. It became a manufacturing town, at that time it was rather a town let.

My maternal grandmother was Elza Merenyi, an opera singer. She was of Hungarian origin. I don’t know when she immigrated to Germany. I don’t know either, why she didn’t sing on stage, whether she couldn’t endure physically or wasn’t allowed to do it because of her origin. It’s sure that there was a pianist, who sometimes came and sat by the big piano and accompanied her as she practiced the scales. But I never heard her on stage. [Editor’s note: The grandmother, Elza Merenyi was the mother of the art historian Mariusz Rabinovszky (1895–1953). Mariusz Rabinovszky wrote the following about the family: ‘My father, Karoly R., who had a tobacco plant in Cairo, died in 1901. My mother, nee Elza Merenyi, she had contracts performing in German operas as an opera singer. When she later married a doctor, she took me to Germany.’ Thus, Elza Merenyi must have gotten to Germany at the beginning of the 20th century, and did perform on German stages.]

My grandmother had a first husband, I know that he only spent a little time here in Europe; he had a tobacco factory in Egypt. I don’t know the name of this grandfather; he might have been the Rabinovszky after whom my mother and her siblings were named. But later my grandmother got married for the second time, to a doctor called Eugen Rappoport. Grandfather Rappoport was a German Jew. He was an ear, nose and throat specialist at the Wuppertal Opera. So he treated the singers. He made a good living. In addition he also treated those who couldn’t pay for free. Grandfather Rappoport didn’t tell us children anything about his work, I only know that he had many patients whom he treated for free. And he didn’t own a car, because he said that he didn’t want to drive over anyone by any chance. Grandfather Rappoport was a little bit of a chubby man; he dressed very elegantly, because he earned a good living. He was very kind to us. I can’t tell you anything else about him.

They had a double-storied villa, they were wealthy. On the ground floor there was the office, on the first floor the entertainment rooms, the music room and the huge dining room. So they had a really good living. The dining room was very nice and elegant. Above it, on the second floor there were the bedrooms, the living rooms and there was the attic, where we had a small room where we could play. We could do anything, there could be chaos, nobody heard it. There was also a maid’s room in the house. Behind the house there was a church, behind the church there was a street, and I saw marches on that street several times. This was already the Hitlerjugend 1, only I didn’t know it.

The house had a tiny little garden. In the middle of the garden there was a cherry tree. The cherries that grew on this cherry tree were as sour as vinegar, we couldn’t eat them, and I felt insulted, that the tree was there for nothing, because we couldn’t eat its cherries. Inside the patio there were all kinds of patterns painted here and there on the wall, which a patient of my grandfather’s had painted in gratitude for the treatment because he didn’t have money to pay for it. There were two domestic servants there, too. A maid and a cook. Cooks at that time didn’t take jobs like this, they rather worked in restaurants. But my grandparents had a cook; my grandmother didn’t do any housework.

My grandparents led a very active social life for quite a while. My grandfather invited big companies. There was a huge dining room, in which there was room for about 20 people, and we, the children, were not allowed to go in there, but there was a smoking-chamber and my younger brother and I stood behind its curtain and peeked in from there. We were curious to see what happened there. If guests came, my parents or grandparents received them on the first floor. Then my grandfather called us to come downstairs and present ourselves, because we were very beautiful kids. And he was proud of us. Grandfather Rappoport and Grandmother Merenyi didn’t have children, but our grandfather loved us very much in spite of the fact that we weren’t his natural descendants.

My grandparents didn’t observe any Jewish customs. They also converted, but I don’t remember anymore when.

We, the children, lived in Hanover, but we spent every vacation at their place. We went to their place by train. There were quite a lot of vacations in Germany, but there wasn’t a two-month summer vacation like here, only a one-month vacation. There was a big vacation in the summer, that was four weeks; there were 10 or 14 days at Easter, 10 days at Pentecost and a fall break in October, which was also 10 days. My brother and sister were born in Wuppertal, because in Hanover my mother didn’t have anyone to help, and in Wuppertal the grandparents helped. They always supported us financially and in other ways, too. I know that I started school there; I went to school there for a year. They provided excellent conditions, especially for children. If he had the time, my grandfather sometimes took us to a pastry-shop downtown. I always asked for a chocolate cake. In Hanover – there we had to go to downtown Hanover, because we didn’t live there but in Hanover-Linden – if we bought shoes for me, for example, we celebrated it afterwards, we went to a cafe, I still remember its name: Cafe Kropke.

My grandfather had two seats for his family in the Barmen Opera. This was also a kind of payment for his medical services. So at vacations, which were during the theatrical season, they always sent me and my sister to the opera. This way I came to know almost all the operas, the most famous operas, without ever having heard my grandmother sing, because she didn’t sing at that time anymore.

My grandparents from Germany disappeared. I don’t know anything about them; I don’t know what happened with them. My grandfather was a doctor and I still hope that he was smart enough to have some poison on him, for them to take before the Nazis could deport them.

My parents didn’t really tell us anything about the way they met; these kinds of things weren’t a topic. My mother attended to our spiritual life very closely. So I didn’t really ask, and my mother didn’t care, because she didn’t like to talk about this.

My father, Hugo Schuller, was an engineer. He was probably born in Budapest, around 1884. I know hardly anything about my father’s family. My father was a Hungarian officer, he did his military service in Dalmatia during World War I, my mother visited him there. Then he got a job in Germany, in Hanover at the Hanomag factory, and then he moved there with his wife and me, because I was already born at that time. [Editor’s note: The Hanomag factory is still operating and manufactures old-timers and trailers.] My father was a furnace engineer, he was employed as such at the factory. He didn’t earn too much, but my grandparents complemented his income. With the job he got an apartment. My father was an exceptionally smart man, he was interested in astrology, I remember that in his free time he devoted himself to astrology.

My mother must have been born around 1890. She was also born in Pest. I don’t really know anything about her childhood, because either it wasn’t a topic, or I don’t remember hearing anything about it. At that time it was in fashion in the family to give the children French names, that’s why she was called Clairette. If anyone talked about my mother in the family they always referred to her as Clairette. I don’t think that anyone had French origin, but at that time a little bit snobbish child rearing was in fashion. They taught my two aunts [Dinora and Henriette] French so much so that later they were unable to learn Hungarian.

My mother was very beautiful and very strict and I adored her. I adored her unconditionally. Otherwise she must have been a playful young girl, she put on my grandmother’s stage costumes – at that time it was customary that not the theater provided the costumes, but the soloists had to bring their own costumes, and my mother took a liking to them and put on my grandmother’s costumes. She had her picture taken in some of them, but I don’t know who took these pictures. Anyhow, I saw that not my grandmother but my mother was wearing the costumes in some of the pictures. My mother also had a very good voice, but she probably didn’t learn to sing, because it wasn’t possible. I remember that I inherited some of her good voice, in my youth I had a very good voice. In the school choir I was one of the soloists, and I remember singing under the Christmas tree in Germany, we also did that in Bergen-Belsen.

I was born in Budapest, the family was Hungarian, a Hungarian Jewish family. I had two siblings: a brother, Istvan [born in 1917] and a sister, Zsuzsa [born in 1925]. My earliest memory is that they handed me in over a train window, and I sat on the lap of a soldier in a train. This must have been soon after World War I broke out. We traveled many times at that time to the grandparents’ in Wuppertal, this must have been on a journey like that.

The apartment in Hanover was very nice, we spent our youth there until our adolescence. There was a bedroom, play-room, living room, bathroom and a kitchen. Our play-room was near our parents’ bedroom. There was a sliding door, which could be closed. Once a girlfriend of mine and I closed the door, and I put a chair on a table and another chair in front of the table. I took the ironing board and I leant it against the upper chair, I don’t know how come it didn’t slip off - and so we had an excellent slide. But the problem was that it didn’t slide. Then I took a washbasin and put it under the ironing board, brought a bucket of water and I sprinkled water on the ironing board and then it slid. But it was too little, so I brought some more water. Someone helped, I don’t know who, one of my girlfriends. Anyhow, when my parents got home they weren’t happy about it at all. There was a terrible scandal, I think I got the only smack in the face of my life from my mother at that time. She never smacked neither me nor my brother or sister in the face. But then I did get a slap in the face.

We didn’t have money to employ a ‘Fräulein’ [German for governess], but there was a lady who took us for a walk every morning. Life in Hanover was quite cloudless, because I was a child there, I had my friends there, I went to school there. My mother packed up the family every Sunday morning, equipped with a can of milk and coffee, a thermos and a ring cake, and there is this nice place in Hanover, a small forest, a little bit like the City Park, and there was a garden restaurant there. So she packed up the ring cake, and in the restaurant we ordered that good German watery coffee. They couldn’t make a good coffee, but it didn’t matter, it was good with the ring cake. Then we played until noon, and at noon we went home. The positive aspect of living in Hanover was that thanks to my grandparents we had no money worries. I inherited very many clothes from my grandmother, she liked to dress very much, she had enough money, and if she got bored of a dress I got it.

My grandfather earned a good living as a doctor, and he paid for us to attend a fencing course. We got equipment, and a fencing sword, too. I was fencing very enthusiastically for a while, but not for long. Hanover had a small river, too, they taught me to swim there. It was a mountain river, and it was extremely cold. I can still feel it on my skin how cold it was.

I know of religious Jews only from my father’s side. But we didn’t keep in touch with them because of the distance, since we could only come home during vacations. There wasn’t any kind of denominational activity, so to speak, at our house. We didn’t observe the holidays either. The younger part of the family converted. I did too, and I also had my confirmation, but that was already in Germany. I became reformed. My brother was baptized in Germany. He was registered everywhere as Stefan Schuller. I know about my brother that he was very talented in drawing, painting, and he made stage sets, scene plans. But he was killed at a very young age, I don’t even know where he disappeared.

In Hanover I had school-mates, friends, we celebrated the birthdays, we lived a completely normal civil life, and that time nobody made us feel that there was a problem. My mother didn’t let us read newspapers. Now I think she obviously did it because people said nasty things about Jews at that time already. But this is just a guess. ‘Politics is not for you,’ my mother said. Politics wasn’t a topic in our family at all. So we didn’t even know what was about to happen. I don’t know whether my father was fired or didn’t want to expose the family to any insults. It couldn’t be seen on my brother that he was Jewish, but on me it could be seen very well. At that time my sister was very small. Afterwards I reconstructed things, assuming that perhaps my father lost his job because of his Jewish origin, and that’s why the family left Hanover. But that’s only my idea, they never spoke about it.

As I’ve said we were raised as Christians, and I didn’t know that I was Jewish until 1932, when I came back to Budapest, I had no idea about it. I was raised in the Reformed faith. Our life had no Jewish character whatsoever, I didn’t know anything besides that only visit to the synagogue. I considered myself a Christian, and it’s interesting, that neither the teachers nor my classmates treated me as a Jew at the German school, though it could be seen on me, they had to see it that I was of Jewish origin. It was a very liberal company. But Hanover wasn’t one of the favorite residences of the Nazis. It was a manufacturing town, everyone was very busy with his own business. I know that my mother had very good Christian friends, they had a beautiful villa with a huge garden in the environs of Hanover, and she always used to go there when she had the time, when my father was away. My father went away on business trips quite often, both abroad and in the country. He was a specialist in his field.

I didn’t go to high school, but there was an institution in Hanover called ‘Höhere Töchterschule’ [German for Upper Girl School], which didn’t give you a high school diploma. It wasn’t eight years but seven years. Only girls went there. We learned all kinds of things. They taught young ladies things like sewing, because a woman has to know this, doesn’t she? But that they taught us how to cook?! Well, that was left out, I had to learn it from my mother. I had to stand next to the stove and watch her make the thickening [a mixture of oil, flour and paprika, which is added to soups and stews]. That really helped me learn it!

Zsuzsa and I were born more than ten years apart. My mother had very shattered nerves, she couldn’t support the little baby, she was a late-born child. From the moment she stopped nursing my sister - she nursed her for quite a long time - she gave her in my hands. My sister and I were very close. In fact I raised her. So much so that later, after the war, I was at their place in Pest many times. I spent every Sunday afternoon with them, and if I had any complaints, she always told me, ‘what do you want, you raised me!?’ So she was so much handed over to me that I brought her up completely.

One of my aunts, Olga Szentpal, the wife of my mother’s younger brother, Mariusz Rabinovszky, was an art of movement teacher. Near Vienna there still exists a big art of movement school, she studied there. [Editor’s note: Olga Szentpal (1895-1968): dance pedagogist, dance researcher, choreographer. Between 1919–1946 she directed her own art of movement school. Then she was a teacher at the National Ballet Institute. Her essays were published in reviews.] Aunt Olga came visiting Wuppertal, I don’t know anymore with whom, and I liked very much what she told us, and I liked her very much, too. One didn’t forget meeting her, she was a character, and then I told her that I wanted to learn to dance at her school. And so it happened. I had never danced before. At school there was physical education, and my mother used to do gymnastics. And there was something between gymnastics and dance, I used to go there, but I don’t know anymore what I learned there.

I came to Pest in 1932. There was a splendid building on City Park Avenue no. 3, that was Olga Szentpal’s art of movement school. I went there, and in the meantime I kept house for my uncle, Mariusz Rabinovszky. Mariusz was a journalist, and there was a German newspaper here in Budapest, I have forgotten what it was called, and he wrote articles for that. [Editor’s note: Mariusz Rabinovszky was a contributor to the theater and arts section of the Pester Loyd, a German newspaper published in Budapest, then after the war he led the Art History department of the Art School until his death.] I didn’t know a word of Hungarian when I came here to Pest, I only spoke German. The Hungarian language was in my ears to some extent, but in the beginning I didn’t speak it. Then I used to go to their place so that my cousins would learn German from me. Well, it happened inversely, because I learned Hungarian from them, and they didn’t learn German. At the time I got there I only had two cousins, the two girls. While I was there a boy was born, who now lives in France with his wife. In the meantime Aunt Olga’s maid left or died, and not only the children, but the entire household became my task.

The school was in the building of the actual acrobat school. This was an art of movement school. Ballet is one thing, and art of movement is another. We learned ballet as a technique, but I never did ballet. I had two friends, one of them later became Gyula Ortutay’s wife [Zsuzsa Kemeny (1913–1982): art of movement, dance specialist. She taught at Olga Szentpal’s art of movement school from 1932 until her marriage.] and her friend, who was an actress. There was a triumvirate, three very talented artists of movement, Lilla Bauer, Zsuzsa Kemeny and Erzsebet Arany. This triumvirate made the school famous at that time. Zsuzsa taught, too, at the dance school, and Uncle Mariusz left me for her, because neither he, nor Aunt Olga had the time to teach me. I learned Hungarian from them. They were very nice, especially Zsuzsa Kemeny. After she married Gyula Ortutay I was in their villa several times, at the time when Ortutay was a minister, and he was never at home. He had a beautiful villa in Pasaret. It was there later, too, and I went to see it. They had a huge garden, a big dog, I was very frightened of, and Ortutay was magnificent, I was quite afraid of him.

I went to Olga Szentpal’s school for many years. Once in 1940 a boy came in and kept looking at me. He sat there for many hours just because of me. He sat there and kept looking at me, I didn’t know that he was looking at me. How he got there, I can’t tell, but I can still see him sitting in front of us on the small bench and staring at me. And my aunt tolerated this. We met in the 1940s. We became close, because he started to court me, he was a very conscious young man, a painter. Once he painted a nude of me, I was pretty, and I remember that I was very offended by the fact that he didn’t give me the nude but sold it. I was so offended by this that I cried all over the place. We were together for about four years. I don’t know how he escaped deportation. I told my sister in the concentration camp that Gyuri was waiting for me. But he didn’t wait until I came home, he probably didn’t count on me returning alive, and he got a girlfriend. I was very much offended by this, and I never wanted to see him again. I don’t even know if he ever found out that in the end I returned. There were a couple of other groom candidates in my life, but I remember them so dimly that it’s not worth mentioning them.

My parents and siblings came two years later, in 1934. Until then I lived at Aunt Olga’s. I know, because I was there, that Aunt Olga and my mother had a fight over me. Because Aunt Olga didn’t want to give me to my mother. They needed me, I kept their house. Aunt Olga worked at the school, Uncle Mariusz at the editorial office, and the kids were there. I don’t know how they came to an agreement, but I went home to my mother, and they returned me in the end. So at that time I was a wanted housekeeper!

I had no idea why we left Germany. I’m sure that my father was fired from the Hannomag in 1934 because of his origin. I didn’t know anything about Hitlerism at that time, my father obviously did. And he thought that here, in his sweet country, he would be more safe. He couldn’t know in advance that he was very wrong. For a very long time we didn’t even live in all this [the gradual Nazifying in Hungary], this was such an isolated world, the Rabinovszky apartment and the Szentpal school. I didn’t care about anything else but dance.

My brother didn’t speak even a word of Hungarian, so he needed a teacher, and he had to learn everything in Hungarian for the high school graduation exam in a year. He didn’t know Hungarian at all, and he had a lot of trouble for a year. He had no talent for languages. But my sister went to school here, and she was very good friends with her cousin Monika, Aunt Olga’s middle child, they went everywhere together, they did all the pranks together. My sister went to a girls’ school in City Park, I don’t remember its name; it was a middle school.

I don’t know anymore how we got hold of it, but we lived is a small apartment on Peterdy Street. There was a play-room, a bedroom, a living room and a bathroom.

I had to earn money, and since I knew German I gave German lessons. I did it for a long time with supreme disgust. But I danced and learned to dance besides it. I loved to dance. I had a part in more than 30 dance shows. My aunt had a piece which had a great impact on me, the ‘Expulsion from Paradise,’ and I was the archangel with the broadsword who expelled Adam and Eve from Paradise. I took on everything what was dance, at that time I was extremely active, I was busy all day long, to my mother’s great disappointment, because I didn’t help at home.

There was a literary society, the Vajda Janos Society, they went to my aunt Olga. [Editor’s note: Vajda Janos Society: a literary society which operated from the end of the 1930s, it was the last citadel of the leftist civil literature. They also published books.] They knew that she had a group. They wanted to popularize Janos Vajda’s poems, and we complemented the presentation of the poems with dance. We went on tour with them to the Balaton, this was sometime after 1934, and it lasted for about a year. [Editor’s note: The tour of the Vajda Janos Society at the Balaton lasted from 1st to 5th September 1937, they held literary and art performances in Balatonalmadi, Balatonfoldvar, Fured, Kenese and Siofok. The ‘one year’ is perhaps a misunderstanding.] I was very happy about it, they took me around the Balaton, and that was my first opportunity to see some of Hungary. This wasn’t a tiresome thing at all. The only tiresome thing was that the leader of this group fell in love with me. This was extremely awkward and annoying for me. Otherwise this tour of the Balaton was a bright spot in my life.

Then my father still worked for quite a few years. He was a well-educated engineer, with practice and independent work. He died around 1937, he had a heart attack. It was a completely unexpected death, because I know that a man came to Peterdy Street one day, he was very nervous because he had to tell my mother the bad news that my father had died in the factory. Since my father was an extremely smart man, in my opinion he knew what was about to happen and that weighed on his mind so much that his heart couldn’t bear it. This is what I think, because he wasn’t ill. My mother got into a terrible state, and all I could care about was to make sure that we have at least our mother left. This was a great love, for decades, during all their marriage. My father’s funeral wasn’t a Jewish funeral. Perhaps they incinerated him. I don’t know, I was busy with other things at that time, because my mother needed much support.

I got a job downtown, at a place called Officer’s Casino as an art of movement teacher. I think it now belongs to the Ship Company. That was a big building, and in the courtyard there was a separate building, and there was a ballet room. I taught German and danced at the same time.

I experienced hardly any anti-Semitism before our deportation. Though it could be seen on me very much that I was Jewish. I didn’t experience any atrocities. But I know for sure that some kind of restrictions applied to me, without me knowing that it was because I was Jewish. So the beginning is completely blurry. I first faced this issue in the car [when the interviewee was deported]. But once my brother got a good beating here in Hungary. I remember this, but I don’t remember how it happened.

The family magyarized their name during the war, because they thought that this way they could avoid this Jewish name Schuller. This is a German Jewish name. So my sister, my brother and I took on the name of my maternal grandmother, Elza Merenyi, and so we became Merenyi. [Editor’s note: Perhaps the magyarizing happened already before 1938. There were no orders or laws, which regulated the magyarizing of the names of Jews, but in practice they didn’t allow the Jews to change their names after 1938.]

We had to move from Peterdy Street, they assigned Jewish houses 2 and they drove all the Jews there.

My friend’s mother accommodated Zsuzsa, my mother and me in her apartment. I don’t know how many of us lived there in three rooms, I think there were three families there. I know that I slept on the floor, because there weren’t enough beds either. We lived in isolation for about half a year here in Budapest, because these were Jewish houses. And we couldn’t move freely, we didn’t know what was going on in the world, we didn’t hear any news. [Editor’s note: They imposed a curfew in the yellow star houses from the end of June 1944, and after that it was only allowed to leave the houses at certain hours.] My mother got to the ghetto from there. My brother wasn’t with us anymore, even in the yellow star house. The Arrow Cross men 3 drafted him into forced labor 4. Then they deported him somewhere in Germany. Later I looked into it, there were countless camps. He was deported to one of them, I don’t know which. He never came back.

Then in the winter of 1944 orders came that all women under 30 had to pack up and go to a certain place 5. [Editor’s note: This probably happened in October 1944 and not in the winter.] My mother was already in the ghetto at that time. The tale was that the Germans were making treaties with Switzerland. Then we found out, I don’t know from whom, or whether it was only hearsay, that the Germans were going to take the Jewish girls under 30 to Switzerland in exchange for medicines. There must have been an organization. Allegedly there was a transport like that before us. But this is all an assumption. I didn’t look into it.

From the yellow star house we set off with small backpacks like cattle. My mother packed food for us. The meeting place was on Teleki Square. We had to register there with our luggage. I don’t know according to what criteria, if it was women, men, or what. I don’t remember. They set us off from the Jozsefvaros railway station, I know. We stood about there for a long time near a train made up of cattle cars, many-many people. Without food or drink, so they didn’t give us any water or food. None of my other relatives were there.

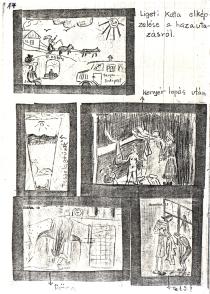

My sister had a copybook, she drew in it all the way there and in the camp, too. I was wondering, ‘How on earth did that copybook get in her backpack when they said that we had to do our packing really quickly? Well, she put it there, otherwise it couldn’t have gotten there. Zsuzsa had never learned to draw, but she drew very well, she made very expressive drawings on the way there. These drawings don’t seem tragic, because my sister had a very good humor, she looked at everything from its humorous side. She even made some kind of toy out of a matchbox.

We got on [the train] and they took us somewhere. We didn’t know where, nobody told us. Until there was food, we ate, until there was something to drink we drank. Then there wasn’t anymore, and we didn’t eat or drink. Once we asked for water from one of these guards; he brought us some from somewhere, and that was oily. There wasn’t a toilet there of course, so the train stopped from time to time, and they let us out, and we relieved ourselves in the cornfields. The weather was rainy and there were puddles everywhere, and we could wash ourselves a little. Otherwise we couldn’t have a wash. This entertainment lasted for about two weeks, because the Germans kept putting us here and there. I found out later that the Germans were already in quite a big trouble, because they didn’t have enough cars to transport their own troops, and that’s why they shuffled the cars hither and thither. But we were lucky, because our transport was one of the last ones.

They made us get off the train in Bergen-Belsen, and from the railway station we went on foot for a very long time, I have no idea for how long. We didn’t know that we got to the relocation camp. And we went in because they told us to go in. We had no idea about anything. Then we saw that there were a lot of barracks. Then we kept going for a while alongside the barracks. In the end they drove us into one of them, the entire transport from Budapest in one barrack. It was jam-packed. My sister and I only had a plank-bed with a straw mattress for a while, so we slept head to toe on a bunk-bed. The bunk bed was so small that if the person on the upper bed hung his foot down from above, it reached the mouth of the person below.

Then ‘Lager’ [German for camp] life began, which was strange because they never took us to work anywhere, this was a relocation camp. But they gathered us into a so-called ‘Sonderlager’ [special camp], so there must have been some truth in the medicine exchange story. Once they took us on a walk somewhere, and then I held my sister’s hand and I said that the gassing was going to come. But they didn’t take us there, they took us on a walk. [Editor’s note: This story is perhaps a special variant of the Kasztner treaties, the ‘blood for goods’ action. There were treaties in reality, even if not about this, but in a completely different context, and the ‘Kasztner Jews’ were really taken to the Bergen-Belsen ‘Sonderlager.’ Bergen-Belsen was originally built as an exchange camp, so they originally deported there those whom the Germans wanted to exchange for someone or something. Lea Merenyi is not a ‘Kasztner Jew’, she can’t be one, because the Kasztner train left the capital at the end of June 1944, it arrived at the camp at the beginning of July, from where the Kasztner Jews were transported to Switzerland in two parts (August and December). Perhaps the remainder of the Kasztner group might have left the camp when Lea Merenyi arrived there, and since the ‘Sonderlager’ was empty at that time, their group might have been accommodated there.]

We only got a minimal amount of food. They were careful though so that we wouldn’t die. There were big brown enameled washbasins, they put everything in those. There was the horrible dishwater that they gave us, and when they distributed the food they commanded ‘bowl down!’, then we banged this washbasin-like thing down, and they poured some food in it with a big ladle. I don’t remember what was in it, but I know that tiny pieces of bacon were floating in it, and I gave them all to my sister. I wanted her to eat it, because she was growing, and I wanted her to get out of this safely. There were long, brick-shaped loaves of bread, and they sliced those up. My sister wrote down on the margin of a drawing, because she was accurate, that a loaf of bread was 24 centimeters long and weighed 150 grams, and they cut those in slices. So we weren’t overfed.

All kinds of ‘skillful’ people [deportees] took from that awful soup, too. There were some who stole bread. That was the capital sin. We put those who stole bread under a ban, we never talked to those again. There was swapping, too. There was someone, I can’t forget this, who gave away all her bread in exchange for a cigarette. This meant death. She couldn’t give up smoking. So such things happened. We didn’t swap. Five of us who had been friends from Budapest formed a small self-supporting community. Two of them were nursery school teachers, the third one never gave anything from her food, the fourth and fifth were my sister and I. The two nursery school teachers held up firmly, they tried to make this thing human. They had some kind of a dish-cloth, and I remember exactly that they set a table with it on their knees. And one of them measured this square bread so that neither one of them would get more than the other.

One of our friends didn’t have her hair cut, and she combed it every day. She had a comb because of the lice. There were all kinds of animals which climbed on us. We kept looking at our clothes to see whether there were lice on them or not. There were some who were taken to work at the weaving mill. But it was forbidden for them to take us, because then we would have gotten weak and wouldn’t have been good exchange goods. So we didn’t work. Once they gathered us in a huge group and took us on a walk, or rather to collect brushwood. But we made a walk out of this. We didn’t collect brushwood but violets.

The Bergen-Belsen camp was a military camp originally. The former military washroom was still there, where the water came from these showers and we could get there through the mud. Once an over-anxious guard yelled at someone to behave like a soldier [i.e. be strong and not whine and complain]. Perhaps the Bergen-Belsen camp erased many things from my memory, because at that time I didn’t focus on anything else but to bring my sister back to my mother safely.

There was a sharp-nosed woman among us, who found out that this Bergen-Belsen camp had a barrack for babies and she signed on as a nurse there. She didn’t know anything, she lied, because she knew that there was food. There was heating, too, they heated with an old iron stove. There was no heating in the barrack. There was a rumor that the parachutists were going to come and liberate us, that’s what they said. But it wasn’t true. And that the Swedish would send us packages. During the Holocaust we were privileged in fact, because they really didn’t hurt us. Apart from the fact that we starved, because that washbasin of soup wasn’t much for a day, they weren’t allowed to hurt us. There were guards with cart-whips, but they didn’t hurt us. So for sure there was some truth in this medicine thing.

There was a very funny thing, a Christmas thing. Somehow it became known that my sister and I could sing Christmas songs in two parts, and it must have been at Christmas 1944 that two or three German officers appeared and called us there, and my sister and I said that that was the end and they were going to rape us: we were still in quite a good shape, we weren’t lousy either. But this wasn’t the case, they asked us to sing German songs in two parts for the officers. We did. To German officers! So such funny things happened there, too. We weren’t there for long, perhaps for half a year or five months, I don’t remember exactly anymore. Liberation happened so that one fine day the gates of the camp were open, and we just looked at each other wondering what that was. Just like that. They didn’t say anything. There weren’t any Germans anywhere. This was the end of April or beginning of May. [Editor’s note: Bergen-Belsen was liberated by the British army on 15th April 1945]

There was a doctor, too. I don’t remember whether we got any medicines, but it’s possible that we did. We were lucky because we were deported quite late, so we weren’t in such poor health that we couldn’t have endured such hardships. We went to the courtyard of the ‘Lager,’ the French Jewish prisoners for example came in groups, buses had been sent for them. And I don’t know who else. They were very nice, and they said, ‘cheer up, go wherever you can, you’re free.’ I know French, so I understood what they said. Then there was a Hungarian man who said that he was going to Budapest, even on foot, and anyone who wanted could go with him. And my sister, our friends and I joined him.

And we set off on foot. That’s how we later got to a deserted German town of clerks, to Trobitz [in Brandenburg province]. There was a block of apartments, and we could go into these clerk houses. We got a room, and my sister fell ill with typhus, which I managed not to get. I nursed her, and I didn’t contract it from her. The Russians were very kind - because the Russians were already there at that time - and we got a big pot of chicken soup with noodles every day, and I could feed my sister with that. So she recovered.

My sister, the three other girls and I, I don’t know why and how, separated from the others. We continued on our way on the main road. Food was a problem, it was a constant problem to figure out what to eat and drink. We were sure, that even if barefoot we would still go home. I remember that there were the five of us, a small group: my three friends, my sister and I. One of my friends fell ill with typhus in the camp, she couldn’t walk. Then we got hold of a small wheel barrow, something that could be pulled by hand, and we made her sit in it and pulled her by turns. But she needed to drink milk. So we went to ask for milk. I was in a German house to beg for milk for my friend, because that’s how we ate, out of alms. And both of us spoke German fluently, and all the Germans believed that we were German refugees. That’s how we got hold of food. We always got something. I know that once I came home with a big loaf of bread, the five of us had enough to eat.

And I remember the following incident exactly: I never dared to tell my sister about it, because she wasn’t a believer. The barrow got stuck, it simply didn’t move, so we were desperate, because it meant famishment, because if we couldn’t go and beg for some food we would be lost. Then I stepped aside and prayed and I said, ‘Dear God, prove it now that you exist!’ We went back to the barrow and we could pull it out. That’s how it was. There must have been some kind of special muscular strength or strength of will, at that time all kinds of strange things happened.

I don’t know for how long we kept wandering, always eastward, but we wandered for a few weeks, until we got home. When we came across a train by accident, we asked where it was going. If it went eastward we got on, but there wasn’t any kind of system in this. The liberation was still very new. I even met a Russian soldier on the field, and I didn’t realize that it was a Russian soldier. I asked him what he wanted. He said that he wanted my watch, because I still had it. My sister told me later that I was stupid, because that was a Russian. My sister and I had an agreement on the way home from the camp, from Bergen-Belsen, I remember it exactly, that we would pretend nothing had happened and continue our life from where we had left off. Of course it didn’t happen that way, but this was our plan.

Our apartment was occupied, we couldn’t move in. A distant aunt of ours lived on Andrassy Avenue. She had a quite big apartment on the second floor, we knew that. So we went to her place and asked her to accommodate us in her apartment. And she did.

At that time the MAV Konzum still existed. [Editor’s note: The MAV Konzum was the consumer’s co-operative of the MAV employees, it was established in 1883.] There was a goods distribution place or something like that at the Keleti railway station. One of my relatives had some connection at the MAV and boosted me into a position there. And there I did administration, I wrote the delivery orders, I wrote invoices, which I didn’t know how to do at all, and everyone laughed at me, and that’s how I could earn money after we returned, so that I could feed my sister. I got some money and I got lunch every day. That was a big thing at that time, because there wasn’t any food. Then my sister came to the MAV Konzum with a small food-carrier every day between 12am and 1pm. People at the MAV were very nice, they put a lot of food in it, she took it home, and the three of us, my sick aunt and the two of us lived of that.

There was inflation, and on payday we had to spend the money within an hour, because in the next hour it wasn’t worth anything. I don’t know anymore how that actually happened, but anyhow, on payday my sister was there, she waited for the salary, took it and ran to spend it all, even the last nickel. This was a sweeping inflation. This job lasted for half a year or maybe a year, so for a short time anyhow. After that I taught German and danced.

The Jews had a search service, and my sister went there to give the details, and ask them to look into them, but they didn’t find anything. I don’t know what this search service was called, but the Jewish Community, the Sip Street center supported it. But otherwise I have never been there, my sister only went there once, when she asked about this. I only know about my mother that she got to the ghetto 6, to a family we knew. There she fell ill, probably of influenza, there was no medicine and she died. I don’t know what the Hungarian ghetto was like, but it probably wasn’t a piece of cake. My sister and I came home from the deportation determined to find our mother first. That helped us endure everything.

When the Communist Party gained power in Hungary they wanted to rope me in. They sent me to a man to help me join the Party, because everyone had to at that time. Then he made a very dishonest proposal to me, saying that he would only help me join the Party if I did ‘that.’ Then I said, ‘No, thanks.’

My sister’s marriage was a simple civil marriage. We never held any kind of Jewish ceremony, because we didn’t even know what that was. They had known each other for a long time, her and my brother-in-law, Gyuri Lorinc. Gyuri had also gone to dance at Olga Szentpal’s, and they had worked together, so they knew everything about each other. My sister said, I remember I was there once, too, that Gyuri and her had decided to get married, since they worked together so much. They weren’t in love with each other, they fell in love later.

My brother-in-law got hold of an apartment somehow, where my sister and he could move in. I never asked how he got hold of that. My brother-in-law wasn’t very talkative, and he didn’t talk with me especially. My sister and I were too close to each other, and he was simply jealous. They lived in Lipotvaros, and I went there for dinner every Sunday.

My sister and my brother-in-law established the Budapest National Ballet Institute. [Editor’s note: Gyorgy Lorinc: ballet-master, ballet director and choreographer, one of the founders of the National Ballet Institute, between 1950–1961 its director and ballet-master. Between 1961–1977 he was the director of the ballet of the Opera house. During his activity the ballet evolved into a company with a modern national and international repertoire of (Western) European standard.] My sister and brother-in-law brought here the Soviet ballet system of that time. They sent my sister to Leningrad and she learned there the Soviet ballet system, and that’s the foundation of the actual Hungarian ballet system, too. My sister and her husband were members of the Communist Party. The ballet institute was established at that time. Only a communist could be the director of such an institute. Neither my sister nor my brother-in-law were convinced communists, they were Communists only because they had to, because of the institute, because they wanted to live of that.

They have both died since then, and I am quite offended by the fact that nobody remembers that she established that. [Zsuzsa Merenyi (1925–1990): she became the private dancer of the Szeged National Theater in 1945. Between 1949–1952 she studied at the ballet department of the Leningrad Academy of Music as holder of a state scholarship, with the classical Russian ballet dancer and pedagogist, who educated generations of ballet dancers, Agrippina Vaganova. After she returned home she worked as a ballet pedagogist: first at the Academy of Theatre and Film, where she taught choreography and ballet pedagogy, then at the National Ballet Institute, where she was the master of the classical ballet. Her researches concerning Olga Szentpal’s life-work are also important.] I don’t remember when the Honved Ensemble was founded. Not a dancer, but a sculptor, Ivan Szabo established it. [Editor’s note: Ivan Szabo: sculptor, choreographer, he was the leader of the Honver Artist Ensemble from 1949.] He knew me, because I had visited the colony of artists where he worked, I don’t know whom I visited there. He knew that I danced and that’s how I became a dancer at the Honved Ensemble. Here everyone was a folk dancer. I was the only one who knew ballet.

I danced at the Honved Ensemble, at that time I had a couple of German students, but I didn’t need that financially, because I had a salary. I was a member of the ensemble for a year, then they did me out, and I took up ballet teaching to children there, in the back part of the Tiszti Kaszino, to earn money. But I still went to the ensemble, I was there at the rehearsals, and I taught, too. In the 1950s and 1960s I taught, because otherwise I simply wouldn’t have had money.

I have very few memories of 1956 7. I know that we listened to the radio. And since I’ve been completely apolitical all my life, I didn’t understand at all what was going on. I only heard that there were crowds, and I heard Imre Nagy’s voice asking for help, but I don’t know from whom. I don’t know whom he spoke to. And that there was trouble. My sister, her husband and their first child lived in Lipotvaros, and I panicked as she was alone there with that small baby. Then, like a madwoman, I rushed there on foot, there was no traffic of course. I can still see myself running over Ferdinand Bridge to Lipotvaros, where they lived, and I spent the 1956 turmoil there.

My brother-in-law was in China, he was invited there to teach ballet. He found out there what was going on, and one day he came home deathly pale, to see whether his family was still there. It was then that he first noticed me because when he got home his first question was, ‘Is Lea also here?’, and this is how the ice broke, because he realized that I wasn’t going to take his wife from him…

I also remember from 1956 that - I don’t know on which day - I was downtown, I had some business there, and a horrible crowd came, and I didn’t know why. I was always afraid of the crowd, ever since my childhood, so I ran home dementedly, on foot. That’s all I know about 1956. There was a radio, but I don’t know what we listened to. I don’t remember unfortunately. So I compensate for what I missed at that time with my reading, because I now read about what happened at that time. I didn’t know it was a revolution. I thought it was some kind of uprising.

I wasn’t a very social person. I had, or I still have a friend, only our relationship got more loose, and I went to several places with this friend of mine. We traveled, we took bus trips, so we paid at a travel agency, and I was in Paris two or three times, in Transylvania, at the Croatian seaside. In fact we have been everywhere in Europe, except Spain.

I like to read. Not long ago I got out some older books, and I still like them. I read all kinds of books. The Mann family is my all time favorite: Thomas Mann, Heinrich Mann. I had a subscription to the Opera, I even had a subscription for concerts at the Academy of Music, I used to go there many times. I used to go to dance shows for a long time, I went to see even the most modern ones.

I retired sometime at the beginning of the 1970s. The change of regime went past me, I didn’t even know that there was a change. So if you have ever seen an apolitical being, that’s me. I got German compensation, and not long ago the Hungarians also paid a smaller amount of money as compensation.

Considering the fact that I’m not getting any younger, my brain is still sound, only my memory got worse. This has always been my weakness. I remember so imperfectly, there’s nothing to do about it. Sometimes I think of my brother, and I think of my grandparents, unfortunately it still stirs my fantasy, I always have to talk myself out of it.

Glossary