Kurt Sadlik

Uzhorod

Ukraine

Interviewer: Ella Levitskaya

Date of the interview: June 2003

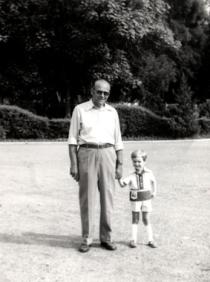

Kurt Sadlik, his daughter Irina and her two children live in a two-room apartment in a new district of Uzhorod. The house was built in the 1970s and the furniture was also acquired about this time. Kurt is a tall, somewhat stooping man. His dark hair with streaks of gray has thinned a little. He is severely ill. He suffers from high blood pressure, heart problems and poor sight. Kurt is a reserved and taciturn man. The horrors of Stalin’s camp taught him to carefully weigh his words. He has never told his daughters or grandchildren about Stalin’s camps or his residence in remote areas. Kurt loves his younger granddaughter dearly. He spends a lot of time with her and enjoys her company.

I know very little about my father’s family. My paternal grandfather, whose family name was Sadlik, died in 1927, before I was born. I don’t even know his first name: my father never told me about his childhood or youth or about his family. My paternal grandmother, Maria Sadlik, is the only one of my father’s family whom I knew. I don’t know her place or date of birth though. All I know is that in the 1880s my father’s family lived somewhere in Austria-Hungary and that was where my father was born.

At the time when I remember my grandmother she was living with her mother in the town of Tuszyn in Poland. I don’t remember my great-grandmother. She was an elderly woman. When I went to school in 1935 I spent all my summer vacations with my grandmother in Tuszyn. Grandmother had a small stone house in Tuszyn. Here were three or four rooms in the house. Grandmother spoke Polish with her neighbors and Yiddish and Slovak to me. She only spoke Yiddish with her mother.

My grandmother was a short fatty woman with a round smiling face. She was very quiet and kind. She had long black hair with streaks of gray that she wore in a knot. She didn’t cover her head. She wore common clothes like all other women in smaller towns at that time. She wore light dresses and shoes with heels.

My grandmother lived in a Polish neighborhood. I cannot say for sure, but I don’t think Jews had their own Jewish district in Tuszyn. I played with Polish children. I remember that grandmother took me to her friends or relatives whose house was also in a Polish neighborhood.

My grandmother wasn’t fanatically religious. She didn’t wear a wig. She went to the synagogue on Jewish holidays and observed Sabbath and Jewish holidays at home. As far as I remember, Grandmother didn’t observe the kashrut. We never heard about my grandmother again after Poland was occupied in 1939 [1]. I think she perished during the German occupation.

My father, Karl Sadlik, was born in Austria-Hungary in 1886. I don’t know his place of birth or his Jewish name. I don’t know whether he had brothers or sisters. I have no information about his childhood.

My mother’s family lived in Slovakia. I don’t know the location, but I think it might have been in Liptovsky Mikulas since at the time when I remember them my maternal grandmother and my mother’s brother and sisters lived there.

All I know about my maternal grandfather is that his last name was Bogner and that he perished during World War I. He was not young, but he volunteered to the front. My maternal grandmother, Othelia Bogner, nee Rot, was born in 1845 or 1846. I don’t know her place of birth or anybody of her family.

There were six children in my mother’s family. I knew four of them. My mother’s two older brothers moved to the USA in the 1900s. I have no information about them. There was no correspondence. As for the rest, I don’t know their dates of birth, but I shall name them in sequence of their birth.

The oldest child was Cecilia. The second child was Iosif and then came Adelina. My mother Irina was the youngest. She was born in 1884. Of course, they had Jewish names, but I don’t know them. At that time children had their secular names written in documents in Slovakian and a rabbi registered the children in a register in the synagogue where the child was given a Jewish name.

Liptovsky Mikulas was a small town. Jews constituted a significant part of its population. I cannot say exactly, but I guess Jews constituted about one third of the total population. There was no Jewish district in the town. Only gypsies [Roma] lived separately. They installed their tents on the outskirts of the town behind the river. Our parents didn’t allow us to go to this area.

Jews enjoyed a free life in Slovakia. It was a truly democratic country. The president of Czechoslovakia, Masaryk [2], who ruled before 1935, and his successor, Benes [3], were intelligent, progressive and democratic people. There were no restrictions for Jews.

There were many rich Jews in the country. In the town there were two leather factories, a knitwear factory, a distillery and an alcohol factory – these were owned by Jews. There were many smaller and bigger Jewish stores. Many Jews were doctors and lawyers. And there were, of course, poor Jewish craftsmen living from hand to mouth.

There were two synagogues in Liptovsky Mikulas. There was a big and beautiful synagogue in the center of the town. It was always full of Jews during the Sabbath and holidays. And there was a smaller one for orthodox Hasidim [4]. There were 10-15 Hasid families in the town.

The majority of the Jews observed Jewish traditions, Sabbath and Jewish holidays, but they were not fanatically religious. It never happened with them that a man would read his religious books all day long and then discuss this with others when his family was hungry, like it happened with Hasidim.

The bigger synagogue is still there. I visited Liptovsky Mikulas in 2000. It was restored and turned into a Jewish museum. Due to the fine acoustic a part of the synagogue was given to the Philharmonic. The synagogue looks as beautiful as when I was a child.

There was a big and rich Jewish community in the town. I don’t know any details about its organization, but I know that the community supported lonely people or poor families. Orphaned children and children from poor families had free education. The community distributed presents on all Jewish holidays: Purim, Pesach, Chanukkah, Yom Kippur and Rosh Hashanah. They provided matzah to poor families at Pesach and food for Sabbath.

My mother’s family was religious. My mother, her brother and sisters knew Hebrew. They prayed in Hebrew and knew prayers by heart. I cannot say where they got religious education. In their family they observed Sabbath and Jewish holidays. They lived in Liptovsky Mikulas with their families.

My mother’s older sister Cecilia was married to a tavern owner. She helped her husband in the tavern and did housekeeping. Their children also helped them when they grew big enough to do work. Cecilia’s husband died and she took over his business.

They had four children: sons Vilo, Altrey and Lazo and daughter Marguta. Cecilia’s older son Vilo made gravestones at the Jewish cemetery. Lazo was a car mechanic and owned a garage. Only wealthy people had cars. Lazo did repairs and gave driving classes. Altrey was an attendant in a hospital. Marguta was married, she was a housewife.

At the beginning of World War II Lazo converted to Lutheranism, though reluctantly. He understood that a Jew didn’t have a chance to survive during the fascist regime. His wife was also a Lutheran.

Cecilia had high blood pressure and Altrey managed to hide her at the hospital where he was working as an attendant. She stayed there throughout the occupation period. Cecilia’s other three children perished in a German concentration camp. This is all the information I have about Cecilia and Altrey.

My mother’s brother Iosif was a tinsmith. He was married, but I didn’t know his wife. She died before I was born. Iosif had two children: son Peter – his Jewish name was Pinchas – and a daughter, whose name I don’t remember. Iosif trained his son to be a tinsmith. They worked together. They roofed houses and installed water piping. The family perished during World War II, only Peter survived.

I didn’t know my mother older sister Adelina’s husband. He died early leaving her with four children: three sons and daughter Zita. After her husband died Adelina became a dressmaker. Adelina’s sons became apprentices of a bricklayer and became bricklayers.

During World War II Adelina, Zita and the sons were in a concentration camp in Czechoslovakia. Adelina’s sons and their families perished in the camp. Zita and Adelina returned home after they were released from the camp. After the war they moved to Israel. Zita got married. Zita and Adelina have passed away and I have no contact with Zita’s children.

I don’t know how my parents met. My mother never told me about it. I think my parents had a traditional Jewish wedding. This had to be so at the time. At least, I know that all of my cousins had traditional Jewish weddings with a chuppah and klezmer music. My parents got married in 1925.

I was born in 1928 and named Kurt. My Jewish name is Itzhak.

After the wedding my parents settled down in the house of my mother’s parents. It was a one-storied brick house divided into two sections: my mother’s sister Adelina lived in one and our family and Grandmother Othelia lived in the other part. There were two big rooms in each section and a big common kitchen in the central part. There were separate entranceways to the house. We lived in the center of the town and didn’t have a garden or livestock. There was a small flower garden near the house and a woodshed in the backyard.

My father drove the only bus in the town that commuted from the railway station to the hotel and then to the Tatry Mountain. There were big caves near our town. There were ancient idols, an ice cave and grottos with stalactites and stalagmites there. It was a place of interest where my father took tourists.

A bus driver was a popular person at that time since cars were rare. Only rich people had cars. There were two or three in our town. The main means of transport were wagons and carts. When I was five or six my father took me with him and all other boys envied me a lot.

My mother was a hairdresser. Before Sabbath and Jewish holidays she did the hair of rich women in their homes. The rest of the time my mother did sewing at home. She sewed bed sheets, nightgowns and fixed clothes. She had a Singer sewing machine at home.

My father wore common clothes. He didn’t have a beard or payes. He didn’t cover his head. My mother didn’t cover her head either. Only orthodox Jewish women wore wigs and dark clothes. My mother had long and very thick dark hair that she wore in a knot. My parents covered their heads only when they went to the synagogue. My grandmother and my mother’s sisters had their hair done in the same fashion. They also wore common clothes in the fashion of this time.

Our family and my mother’s relatives were religious. We had faith in God and prayed. We observed traditions, but we didn’t always observe the kashrut in everyday life at home.

On Friday my mother made food and baked challah for Sabbath. There were two Jewish bakeries in the town: one owned by Altman and another was owned by Nyumberg. Mother made dough for challah and plated it. She also made bagels and rolls. She put those in a big canvas bag and covered it with a white napkin. I took this bag to the bakery: they did it for peanuts. In the afternoon I picked up the pastries. I can still remember the wonderful smell!

In the evening my mother lit candles and prayed over them. We recited a prayer and sat down to dinner. On Sabbath our Christian neighbors came to stoke the stove to warm up the food and to light lamps.

My mother and father went to the synagogue on Sabbath. My mother took me with her. Many women took their children to the synagogue with them if there was nobody to leave them with at home. Women were on the second floor at the synagogue. There were three rows of seats with stands for prayer books.

We made a general cleanup of the house before Pesach. Our fancy crockery that we only used at Pesach was stored in the attic. We took it from there before Pesach and kept it in the boiling water. Everyday utensils were taken to the attic.

We bought matzah in the Nyumberg bakery. That matzah was different from what they make nowadays: those were round-shaped thin flat cookies baked on charcoal in ovens. It was such yummy matzah! Present-day matzah has a different taste. The recipe is the same: water and flour, but the taste is different. The matzah of my time was crispy and I enjoyed eating it. Present-day matzah is like straw, far from what I remember.

We didn’t have any bread at home throughout the eight days of Pesach. Mother cooked traditional Jewish food at Pesach: chicken broth with matzah, fried chicken or geese, stuffed gooseneck, pudding with matzah and eggs and strudels with jam, nuts and raisins. We only had kosher food at Pesach.

We spent both seders at Aunt Cecilia’s home. We visited them after the synagogue in the morning and stayed almost until the next morning, the end of seder. Her son Altrey, the one who converted to Lutheranism during World War II, was very religious at that time. He conducted the seder. They had a big room and a table big enough for all of us. The family got together, said a common prayer [broche] and then sat down to a meal.

During seder each of us including children was to drink four glasses of wine. Of course, children had small glasses. In the center of the table there was an extra glass for Elijah the Prophet [5]. The front door was open for him to come into the house.

It didn’t usually happen that people stopped working throughout the eight days of Pesach. Only on the first and the second day when the first and second seder was conducted nobody worked. On the other days a person could decide for himself whether he needed to do some work or not.

Our father worked from the third day of the holiday to the last, eighth day. There were tourists coming to town and they needed a bus to transport them. My father made an arrangement with his colleague to have the first two days off at Pesach. When my father was at work my mother and I visited relatives and had guests at home.

At Rosh Hashanah my mother always made a festive meal. In the morning the family went to the synagogue to pray. At Yom Kippur adults fasted. They had dinner a day before Yom Kippur before the first evening star. They tried to have a bigger meal since they had 24 hours ahead of them with no eating.

I remember that my mother and aunt Adelina stuck cloves into an apple that they took with them to the synagogue. When they couldn’t stand the hunger any longer, at 3-4pm, they smelled these cloves. Its heady smell made them feel better. Children fasted from morning till lunch and adults fasted until the first evening star appeared in the sky.

I remember Chanukkah very well. My mother put a big bronze Chanukkah candle stand and lit one more candle every day with the same candle. All Jewish children received presents from the Jewish community: bags full of candy, peanuts and chocolate. Our guests always gave me some money at Chanukkah.

At Purim performers came to Jewish houses. They were wearing costumes to act as characters of the Book of Ester: Mordecai, King Ahasuerus and Haman, the villain of the story. The performers sang songs asking to give them a few coins for their performance. When I turned six I also performed in houses. We were given some change, candy and honey cakes.

At the age of six I went to a Jewish school in a beautiful two-storied building in the neighboring street. There was a synagogue near the school. We attended this synagogue. Our school was called cheder, but besides religion we studied general subjects: mathematics, Slovakian and German languages, history and geography. Boys and girls went to this school. It was a school for boys and girls.

We also studied Jewish religion and traditions. A rabbi taught us to read and write in Hebrew and Yiddish and translate from Hebrew to Yiddish. We learned prayers by heart and later read them when we learned to read in Hebrew. The rabbi read articles from the Torah and we discussed them.

I studied well. My favorite subjects were history, geography and Hebrew. I didn’t like mathematics. I just hated it. Before Purim we prepared Purimspiel performances. We performed in the school concert hall at Purim. Our spectators were our families. We also gave concerts at Chanukkah.

There were no sport clubs at school. There used to be a football club, but for some reason it was closed. I was a sociable boy and got along well with other children at school. I had four close friends. Of course, my school friends were Jews. Later, when I grew older, I had Christian friends.

In the 1970s I traveled to Czechoslovakia. I went to where my school was. It was still there; only it had become a vocational school. When I came to Liptovsky Mikulas in 2000 the school was not there any longer.

In 1935 my grandmother Othelia died. She was 89 or 90 years old – I don’t know for sure. My grandmother was buried in the Jewish cemetery. There was a Jewish funeral. There were two Jewish cemeteries in Liptovsky Mikulas: one from the 19th-century and the new one. In 1936 my father caught a cold and died. He was buried near my grandmother’s grave. The funeral was Jewish as well. My mother’s brother Iosif recited the Kaddish after him.

I was eight when it happened. Our life changed for the worse. My mother had to work more: she did wealthier women’s hair and sewed at home. I also went to work. There were Bulgarian farmers in our village growing greeneries and vegetables. On summer vacations I did field work for them: weeding or pricking out. I got my daily earnings.

I also hauled brushwood for stoves from the power saw facility to the store where they were selling it. They were bundled into 5 kg piles. I hauled five to six bundles to the store located some 15 kilometers from the saw facility. I earned little, but I could pay for a ticket to the cinema or buy some lollipops.

The Jewish community also supported us giving my mother a suit, a coat or a pair of boots for me since I was outgrowing my clothes fast. It also provided food for Sabbath and other holidays. There was a leather factory that belonged to the Geksner brothers in our town. They were very rich. The older brother held me during my brit milah. After my father died he always supported us with some money.

Jews had equal rights as Slovakian citizens. In 1939 Hitler attacked Poland. We were concerned about what was going to happen next. On the radio they often broadcast Hitler speeches. The local population knew German. We spoke Yiddish at home for the most part, and sometimes we spoke German and Slovakian. I took no interest in politics then, but I could feel how concerned and even scared my family was.

In 1939 fascists appeared in Slovakia. They called themselves People’s Guard [6]. They wore black suits with armbands. They were Christian and Catholic, of course. They were rabble that didn’t want to work, but torture and rob Jews. In 1940 German fascists occupied Czechia. Local fascists ruled in Slovakia [7]. Jews began to be persecuted.

In fall 1941 Jews were ordered to wear yellow stars [8] on the chest and arm, and were not allowed to go out without them. However, there was some Jewish life. The synagogues were open and Jews could attend them. In 1941 I turned 13 and had a bar mitzvah at the synagogue.

In spring 1942 all Jews in Liptovsky Mikulas were ordered to gather in the yard of the synagogue near my school. Ordered means fascists came to Jewish houses and told people to gather in the yard of the synagogue. They said that people didn’t need much luggage, just for two or three days. They said that people didn’t have to worry about their houses, they would be sealed.

People went there as obediently as sheep to a slaughterhouse as if they were hypnotized. I still cannot understand how come they didn’t resist, but kept praying and wondering what was going to happen to them. Of course, nobody knew that they were going to die.

My mother and I and my mother’s sisters and brother and their families went there, too. There was a two meter high fence around the yard. Beyond the fence there was an old Jewish cemetery. We didn’t have any idea what was going to happen to us.

I cannot explain why my friend and I decided to climb over the fence to the old Jewish cemetery at night. My mother didn’t know about it. From the cemetery we went to somebody’s yard and from that yard we escaped to the forest where we stayed. Then my friend left me. His parents’ acquaintances lived in a neighboring village. He wanted me to go with him, but I was afraid since there were fascists in villages as well. I never saw him again. I don’t know what happened to him.

I was hiding in the Lower Tatry. I lived in a shepherd’s abandoned hut, in a ‘kolyba’ made of branches. There was a stove inside. These huts were usually made near a stream or spring to have potable water.

Every now and then woodcutters came to the hut. They were aware of my whereabouts, but I still hid in the woods from them. When I returned to the ‘kolyba’ I found bread, boiled potatoes and milk. They were nice people. They didn’t have much food, but they shared with me whatever little they had. They didn’t give me out to the Germans either.

In summer and fall I ate berries and eatable roots. There were lots of mushrooms, but I was afraid of making a fire in the stove to cook them for safety reasons. I didn’t have matches either. It was cold in winter. I picked pine branches to sleep on them. Anyway, I managed there until the winter of 1943-44 and never caught a cold.

In winter 1943-44 some Russian parachutists landed nearby. I didn’t know who they were and hid in the woods. I heard some foreign languages they spoke, but it wasn’t German. They saw branches and food leftovers in my hut and understood there was someone living in it. Of course, it took them little time to find me. I didn’t know Russian, but there was a Slovakian translator with them.

I was fluent in German and the Russians took me into their group. I was a kind of spy for the Russians. I put on farmer’s clothes and went to villages to investigate where the German troops were and listen to what the Germans were saying.

On 29th August 1944 the Slovakian people’s riot began [9]. Many partisans came from the mountains. There were many Germans and Slovakian fascists killed. For five months fascists were having problems with moving their troops to the USSR across this area. Then German troops were sent there to fight with partisans and partisans had to go back to the woods. Partisans were staying in the woods until February 1945, and I stayed with them.

In 1945 I went home looking for my mother. My aunt Adelina and my mother returned home from a concentration camp. In winter 1945 German troops began to attack our town again. In March we had to escape to the town of Poprad in the east of Slovakia, some 30 kilometers from our town. A local Jewish woman offered us accommodation in her house. We stayed there a few days.

I was a little over 16 years old. Мy mother and I didn’t discuss what happened. We reached a silent agreement that we would not discuss things, but wait until our recollections became less painful. Well, I never got to know in what concentration camp my mother was.

A few days after we arrived at Poprad I was stopped by two Russian soldiers with automatic guns. They asked me something in Russian. I didn’t understand what it was about and they convoyed me to a KGB office [10]. They kept me in a cell for few days and then I was taken to a prison in Slovakia. I don’t know where it was.

In a few days I was taken to court. There were three people sitting at the table. They had some papers in front of them. They asked me something that I didn’t understand. They spoke Russian and there was no interpreter. The only thing I understood was ‘ten years’: it sounds similar in Russian and Slovakian.

I was taken back to prison and then convoyed somewhere else. I didn’t understand what the charges were. I didn’t have an attorney. They didn’t allow me to say ‘good bye’ to Mother or write her a letter. I never saw her again.

We went across the mountains and covered 150 kilometers. We reached Cracow. The town was ruined and destroyed. The only undamaged building was a prison. We were kept in this prison for two months. It was stuffed with inmates who were no less scared than I. They were accused of cooperation with the fascist regime only because they survived. Actually, this was our guess since there was no investigation. We didn’t even get to telling them about ourselves.

Every day groups of prisoners were transported by train to the Gulag [11] in the north of the USSR. One day it was my turn. We were taken to a distribution camp in Magadan and from there we were convoyed to Norilsk in the permafrost area over 4500 kilometers from home.

There were camps – long wooden barracks with primitive two-tier plank beds – on the outskirts of the town. The camp was fenced with electrified barbed wire. On four sides there were guard towers. Soldiers with shepherd dogs patrolled the area. The dogs were specially trained to guard the inmates.

I was a political prisoner and stayed in a camp for political prisoners. There were criminal prisoners as well. They lived in more comfortable barracks that had better heating. We had stoves on the opposite sides of the barrack. They heated maximum 3 meters in the barrack and the rest of it was very cold. At night we took turns to warm up by a stove. In the morning we lined up and then convoyed to work at a mine. We returned to the barrack in the evening.

I don’t feel like talking about my life in the camp. It is unbearable to recall this time. There are lots of publications on this subjects and one can read about it in Alexandr Solzhenitsyn’s [12] or other writers’ novels and stories. All I can say is that our life was no different from how Solzhenitsyn described it.

Hundreds of thousands of innocent people were suffering and dying there. I worked at a mine until an old man who worked as an electrician felt sorry for me. I became his apprentice. I was an industrious apprentice and learned what I needed in a short time. I began to work and my life became easier.

I was released in 1953 after Stalin died. The director of the camp called me to his office and just said ‘Released.’ I was in prison for six years of my ten-year sentence. For many people Stalin’s death was a shock, even in the camp, but not so for me. I was happy that such a monster of cruelty croaked. However young I was I understood that all this suffering was his doing.

I obtained a certificate of release at the head office of the camp. My name was written as Karol Karolevich instead of Kurt Karlovich in it and they wrote a wrong year of birth: 1926 instead of 1928. Perhaps, they made me two years older intentionally to make me of age in court. I don’t know.

This certificate was my only document. I didn’t have permission to leave Norilsk, though. Every Saturday I had to register at the district militia office. I worked at the same mine where I had worked being a prisoner. The only difference was that I lived in a hostel for employees. There were seven of us in a room. I had meals at a diner at the mine. The accounting office deducted the cost of meals from my salary and the rest of it was mine.

I met my future wife in the hostel. She wasn’t a prisoner. Ludmila Protopopova was Russian, she was born in Novosibirsk in 1922. I know little about her family. Her father, Ignat Protopopov, went to the army and perished at the front during World War II. Ludmila’s mother starved to death. Ludmila couldn’t find a job in Novosibirsk after finishing a secondary school. She went to Norilsk where her maternal aunt lived and went to work as assistant accountant at a mine.

We began to see each other. I couldn’t marry Ludmila even when she got pregnant. The only document I had was my certificate of release. I was eager to restore my Slovakian citizenship, but it was out of question. In all offices I addressed they told me this was impossible.

I had little choice: either rot to death at the mine in Norilsk or obtain Soviet citizenship however much I hated this country. And I got this damned Soviet citizenship. We lived in Norilsk until 1955 and after I became a Soviet citizen we went to Novosibirsk, Ludmila’s home town. In 1956 our daughter Vera was born.

Throughout this whole period I was trying to find out what happened to my family in Slovakia. I started writing letters when I was allowed. I don’t think those letters ever crossed the border of the USSR. All letters were censured and read by KGB employees. I tried to search for my family through the Red Cross. I received their response ‘Neither found dead nor alive in Czechoslovakia.’ It also said that my mother, Irina Sadlik, nee Bogner, died in 1947.

In Novosibirsk I began to work as an electrician at a construction site and entered an extramural department in the Novosibirsk Energy Technical School. My wife got a residential permit [13] to live in Novosibirsk while I was not allowed to reside in big towns. I was allowed to live in a village 15 kilometers from Novosibirsk where I received a room. Every day I had to get a ride to work. It was hard and I even quit school three months before graduation.

Ludmila’s distant relatives lived in Petropavlovsk, Kazakhstan. We decided to move there to be close to at least some relatives. In Petropavlovsk I went to work at the construction of a big power plant where I was an electrician. We received a room in a hostel. Ludmila looked after our daughter Vera. In 1958 our younger daughter Irina, named after my mother, was born in Petropavlovsk.

We lived in Petropavlovsk in 1958–1959 until I got to know that in Subcarpathia [14] the border was open and it was allowed to move to Hungary and Czechoslovakia. There was always an Iron Curtain [15] separating the USSR from other countries or how else would Soviet people believe that life in the USSR was better than in other countries.

I saved some money to buy tickets and we moved to Uzhorod. It turned out that it was during a short period after World War II when it was allowed to move from Uzhorod, but it was over in 1946. What were we to do? We didn’t feel like going back to Kazakhstan. We decided to stay in Uzhorod.

We didn’t have a place to live or work. We rented a room and our heart sank every time there was a knock on the door. We were afraid that a district militia would come. We didn’t have residential permits. It was like a closed circle: when I came to a job interview they told me that I needed a residential permit to get a job and when I went to the militia office to request a permit they replied that they would only issue it if I got a job.

Fortunately, our landlords were kind people. They helped us to obtain a permit for temporary residence and this was sufficient for me to get employed. I went to work as an electrician at the distillery. We received a room in a half-ruined barrack. I repaired it myself. The four of us lived in this room for 14 years.

In 1971 I left the distillery and went to work at the alarm systems non-governmental security department. In 1973 I received a three-room apartment from my work. I’ve lived in this apartment for 30 years.

I’ve never faced any anti-Semitism after World War II. I’ve always identified myself as a Jew. I learned fluent Russian. I worked in the environment of plain people who express themselves with curse language for the most part. I learned this curse language as well. It never occurred to them that I might be a Jew since they knew that Jewish men never cursed for their fear of God. My principle was ‘when in Rome, do as the Romans do’. I had to get adjusted.

However, I was aware of everyday and governmental anti-Semitism in the USSR. My Jewish acquaintances had problems with getting a job or entering higher educational institutions. There were many such examples and I knew that there was more to it than we could think of. It started during Stalin’s rule and couldn’t have been initiated by some lower officials.

My wife was very concerned about our daughters. I was thinking about this, too, and resolved this issue in the manner that occurred to me at the moment. I submitted a report to a militia office that I had lost my passport. I was fined and had to wait for some time until I obtained a new passport where my nationality was identified as Slovakian. I believed that I had a right to protect my children from this state with whatever means available. Besides, frankly speaking I did not quite worship a Soviet passport.

When Khrushchev [16] at the Twentieth Party Congress [17] denounced the cult of Stalin and spoke about the crimes of the Soviet regime I had a dual feeling. Of course, it was a criminal regime and a criminal leader: I went through it myself. But Khrushchev and others who were blaming Stalin had been on top during his rule. Couldn’t they do anything? Why did they keep quiet? Were they so much scared of Stalin or Beriya? [18] There were many more than Stalin and Beriya. They were afraid and didn’t want to lose their post or life.

I don’t believe anybody. Khrushchev made a good beginning and how did it end? Promises to catch up with and surpass America? With what: with slogans and empty stores where it was always a problem to buy even a pair of socks? Could I believe him? Nowadays I don’t have much hope either that Ukraine will become free, wealthy and independent. Things are different in reality.

After the release from the camp I didn’t observe any Jewish traditions, although I felt the need to do so. My wife didn’t care about religion while I wanted to talk with someone in Yiddish, observe a Jewish holiday and pray on Sabbath, but I didn’t get a chance in the North or in Kazakhstan. There were very few Jews there. There were not even ten for a minyan and there was no synagogue in Novosibirsk or Petropavlovsk.

We didn’t celebrate Soviet holidays at home. I participated in meetings at work when I had to. Naturally, I didn’t join the Party and nobody ever suggested that I did considering that I was a former convict. However, I would have never joined this disgusting Party anyway. What can one say? This Party destroyed everything good, nice and decent and built its world of fear, violence and tyranny on the ruins!

My wife and I had a good life. There were just the two of us in the whole world. We often spent vacations at the seashore. When I found my cousin we traveled to Slovakia every now and then. For residents of Subcarpathia traveling to Slovakia was easier than for the rest of the USSR.

Most of my friends in Uzhorod were Jews. It wasn’t just a coincidence since I looked for Jews in every place I came to. However, Soviet citizens were reluctant to make new friends. It wasn’t their fault, I understood that any person might happen to be a KGB informer and people tried to secure themselves. When I approached a man of Semitic appearance whether he was a Jew he rushed to reply ‘no’ and go away.

For me nationality was always important. I believed that I could have more trust in Jews and I thought that only with them I could feel at ease. Perhaps, this was something subconscious since Russians, Ukrainians and other nations living in the USSR were different to me while Jews were always Jews whether they were in the USSR or Slovakia.

When I lived in Uzhorod my neighbor became my friend. There was a synagogue in Uzhorod and my neighbor offered me to go to the synagogue together. I was happy to go with him. He introduced me to others at the synagogue.

They didn’t like the name of Kurt and began to talk that I wasn’t a Jew. I didn’t look like a Jew. Then the senior man came. I talked to him in Yiddish. I said I could present an immediate proof that I was a Jew. He allowed me to stay for a prayer.

I felt hurt: I didn’t think they could treat a man who came to the synagogue in this crude manner. However, I understood that they were afraid of traitors and informers since life in this country taught everyone to be on guard.

My wife also asked me to stop going to the synagogue since the state persecuted religion and she was afraid that it might not be good for the children, either. I resumed going to synagogue after my wife died in 1993.

In 1968 I finally found my only relative in Czechoslovakia: my cousin Peter, my uncle Iosif’s son. An aunt of my wife’s acquaintance came on a visit from Czechoslovakia. My wife told her the story of my family and that I couldn’t find my family. That woman promised to help me.

Soon after she left for Czechoslovakia we received a letter with my cousin’s address from her. We began to write letters. My cousin sent me my birth certificate. He also sent us an invitation letter and in 1970 my wife and I went to visit him.

In Liptovsky Mikulas I got to know that almost all my relatives of my family and friends perished in a camp near the town and were buried in a common grave near the old Jewish cemetery. My aunt Cecilia’s two sons and a daughter, my mother’s brother Iosif and his daughter, and my aunt Adelina’s three sons and their families perished in the camp.

My mother died in 1947 and was buried in the same cemetery. In 1970 a huge marble board with the names of Jews, residents of the town who perished during World War II, engraved on it was installed at the entrance to the cemetery. I found the names of our relatives and my school friends on this board. There is a monument installed at the beginning of the cemetery.

When I came on another visit in 1991 there was nothing left. The cemetery and the monuments had been removed. They didn’t remove the graves to another location. They graded the area and planted a park. It was a blasphemy for me.

I walked along the asphalted walkways in the park recalling the spots where my grandmother, mother, cousin sister and father were buried. There were benches on their bones. This was heartbreaking. It was fearful. This was humiliation of the dead and mockery on the memory of the living. They had removed the two-meter high fence around the cemetery and the memorial board.

When Jews were leaving for Israel in the 1970s I didn’t consider emigration. Firstly, we didn’t have enough money to move there. Secondly, my wife didn’t want to move there. I, actually, didn’t take any effort to convince her. ‘Look before you leap’ is my principle. I didn’t even want to move to my Motherland. My wife liked it in Slovakia and she wished we moved there.

I decided to move to Slovakia, but then I thought, ‘Who needs me there with two children? My mother and my father are gone. I have no sister or brother there. Does my cousin brother need me? He has his family and his cares.’ Besides, I realized that I would always be an immigrant from the USSR. And there was no friendly attitude toward the USSR. I had a job and an apartment here. I earned my living and I didn’t feel strong enough to start my life from zero. I considered this – and stayed here.

In the course of many years I wrote in all application forms that I had served a sentence in prison, until in 1991 I received a letter of rehabilitation [19] from the KGB office in Moscow due to absence of corpus delicti. It said that the court verdict in my case was illegal. And, of course, they misspelled my name and put a wrong year of birth. Well, let them, but who is responsible for my broken life, for the youth spent in camps, for my life here? Nobody is responsible…

I won’t mention my daughters’ and grandchildren names. I’ve lived my life and I do not have fears for myself, but I fear for them. Even though the Communist Party is not in power in independent Ukraine any longer, but communists are too ardent in their strive for power. I fear to think what it would be like if they ever take power again. I don’t want my daughters or grandchildren to have problems just because I am too open here.

My girls were nice and obedient daughters when they were children. They always knew that their father is a Jew, but nationality didn’t matter to them. Vera, my older daughter, graduated from the Technical Faculty of Uzhorod University. She went to work as an engineer in a design office.

Vera is married to a Ukrainian man. She has two children. Inga, the older one, was born in 1976. Inga studies at the Physical Culture College. Rodion was born in 1977. After finishing a lower secondary school he finished a Computer College with honors. He works in a computer repair shop. Vera and her family live in their apartment in Uzhorod.

My younger daughter Irina married a Jewish man. She has two children. Her older son Denis was born in 1978. Denis finished a lower secondary school and didn’t want to continue his education. He is a baker. My younger granddaughter Olga, born in 1991 goes to school. She studies well. I spend a lot of time with her. I enjoy these moments.

When perestroika [20] began in the early 1980s I understood that the Soviet power was coming to an end. I wouldn’t argue that we’ve gained freedom, but who knows when and what price we shall have to pay for it? People got freedom and an opportunity to travel abroad. They see live in capitalist countries and they’ve changed their outlooks. Yes, things were less expensive in the Soviet Union, but there were long lines to get even a piece of meat!

However, I didn’t think the Soviet regime would collapse that fast. It was powerful, indeed. And all of a sudden it ended in a day. I was positive about the downfall of the USSR. Of course, it should have been arranged differently. There were economic ties between the republics that were also broken. Factories in Uzhorod cooperated with Kazakhstan, Siberia and Moscow. Those ties are gone and nobody cares.

Machine building, mechanic, equipment plant Uzhorodpribor, Electric Engine, gas equipment plants were shut down. Nobody needs them and nobody cares about former employees. It’s like communists whose slogan was ‘we shall destroy to foundations the world of violence and then…’ Well, they’ve destroyed the past. But God knows what they will build.

People of power are all the same, only now they call themselves democrats and yesterday they were communists. They don’t care a bit about people who are like cattle for them.

I don’t believe in anything with this government. They take loans from abroad for restoration of industries and where is this money? What industries have they restored? People sell rags in markets: they are former professors and academicians. Teachers and doctors are miserably poor. People search for food leftovers in garbage containers. There were homeless dogs looking for leftovers in garbage pans, but not people. The situation is terrible.

I am against communism, but it has never been like this. One could make ends meet during the Soviet regime. Children could study and education was mandatory. Nowadays nobody cares whether a child is at school or in the streets. The state doesn’t need us. There are no jobs; people have to think by themselves how to live on… Is this democracy? No, policy is truly disgusting!

Jewish life in Uzhorod revived during perestroika. Jews could go to the synagogue without fear that someone would see them. When Ukraine gained independence the Jewish life began to develop rapidly.

I am very pleased that my younger granddaughter identifies herself as Jew. Olga has attended a Jewish school for two years. I told her that there was such a school and she wanted to go there. I took her there for the first time since she was a little shy, but then she began to go there every Sunday. Olga took part in their performance at Purim. They sing and dance at school. This year [in 2003] Olga attends an evening club at Hesed [21] where they study Ivrit.

We observe Sabbath at home and have a festive meal. Olga lights candles and prays over them. My daughter Irina observes it with us. Regretfully, my other grandchildren don’t care about their Jewish identity. Olga enjoys her studies and I hope she will learn everything a Jewish girl is supposed to know while I am with them.

Since Hesed was established in Uzhorod in 1999 our life became easier. Hesed takes care of Jews: from infants to old people, it provides a big assistance to Jews of all ages. There are clubs of interest and everybody can find interesting things to do there.

Young people become more interested in the Jewish life. My granddaughter is an example of this interest. We observe Jewish holidays in Hesed, they are wonderful: bright and joyful. There is a computer club and foreign languages clubs. There are no age restrictions. They provide diapers and baby food to mothers with babies and support old people.

I am deputy chairman of social assistance in Hesed. Hesed provides money to buy medications for elderly people on a monthly basis. They also make arrangements for free treatment in hospital, if necessary. Relatives don’t need to bring medications to a hospital. Hesed pays for all necessary medications. There are doctors in Hesed. We have a therapeutic office of physical training in Hesed. There is a free swimming pool. Swimming helps older people to stay healthy.

There is a free barber and hairdresser in Hesed. There is free manicure. They also help invalids. Handicapped receive free wheel chairs. They are very expensive and people cannot afford to buy them. There are all kinds of supporting devices for ill people that are very important.

Old people receive food packages and hot meals delivered to their homes. Hesed does necessary repairs of private houses, fixes leaking roofs. Hesed also supplies gas to those that use gas in containers. There are three-day recreation camps for parents and children. Children can go to a health camp in Hungary for one month. Children like it there a lot. I cannot imagine life without Hesed and what we would do without considering the reality of today.

Glossary

[1] German Invasion of Poland: The German attack of Poland on 1st September 1939 is widely considered the date in the West for the start of World War II. After having gained both Austria and the Bohemian and Moravian parts of Czechoslovakia, Hitler was confident that he could acquire Poland without having to fight Britain and France. (To eliminate the possibility of the Soviet Union fighting if Poland were attacked, Hitler made a pact with the Soviet Union, the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact.) On the morning of 1st September 1939, German troops entered Poland. The German air attack hit so quickly that most of Poland's air force was destroyed while still on the ground. To hinder Polish mobilization, the Germans bombed bridges and roads. Groups of marching soldiers were machine-gunned from the air, and they also aimed at civilians. On 1st September, the beginning of the attack, Great Britain and France sent Hitler an ultimatum - withdraw German forces from Poland or Great Britain and France would go to war against Germany. On 3rd September, with Germany's forces penetrating deeper into Poland, Great Britain and France both declared war on Germany.

[2] Masaryk, Tomas Garrigue (1850-1937): Czechoslovak political leader and philosopher and chief founder of the First Czechoslovak Republic. He founded the Czech People's Party in 1900, which strove for Czech independence within the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, for the protection of minorities and the unity of Czechs and Slovaks. After the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy in 1918, Masaryk became the first president of Czechoslovakia. He was reelected in 1920, 1927, and 1934. Among the first acts of his government was an extensive land reform. He steered a moderate course on such sensitive issues as the status of minorities, especially the Slovaks and Germans, and the relations between the church and the state. Masaryk resigned in 1935 and Edvard Benes, his former foreign minister, succeeded him.

[3] Benes, Edvard (1884-1948): Czechoslovak politician and president from 1935-38 and 1946-48. He was a follower of T. G. Masaryk, the first president of Czechoslovakia, and the idea of Czechoslovakism, and later Masaryk's right-hand man. After World War I he represented Czechoslovakia at the Paris Peace Conference. He was Foreign Minister (1918-1935) and Prime Minister (1921-1922) of the new Czechoslovak state and became president after Masaryk retired in 1935. The Czechoslovak alliance with France and the creation of the Little Entente (Czechoslovak, Romanian and Yugoslav alliance against Hungarian revisionism and the restoration of the Habsburgs) were essentially his work. After the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia by the Munich Pact (1938) he resigned and went into exile. Returning to Prague in 1945, he was confirmed in office and was reelected president in 1946. After the communist coup in February 1948 he resigned in June on the grounds of illness, refusing to sign the new constitution.

[4] Hasid: Follower of the Hasidic movement, a Jewish mystic movement founded in the 18th century that reacted against Talmudic learning and maintained that God's presence was in all of one's surroundings and that one should serve God in one's every deed and word. The movement provided spiritual hope and uplifted the common people. There were large branches of Hasidic movements and schools throughout Eastern Europe before World War II, each following the teachings of famous scholars and thinkers. Most had their own customs, rituals and life styles. Today there are substantial Hasidic communities in New York, London, Israel and Antwerp.

[5] Elijah the Prophet: According to the Jewish legend the prophet Elijah visits every home on the first day of Pesach and drinks from the cup that has been poured for him. He is invisible but he can see everything in the house. The door is kept open for the prophet to come in and honor the holiday with his presence.

[6] People’s Guard: Fascist organization in Slovakia between 1939-1945. The People’s Guard propagated nationalist, Christian-mystical and anti-Semitic views.

[7] Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia: Bohemia and Moravia were occupied by the Germans and transformed into a German Protectorate in March 1939, after Slovakia declared its independence. The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was placed under the supervision of the Reich protector, Konstantin von Neurath. The Gestapo assumed police authority. Jews were dismissed from civil service and placed in an extralegal position. In the fall of 1941, the Reich adopted a more radical policy in the Protectorate. The Gestapo became very active in arrests and executions. The deportation of Jews to concentration camps was organized, and Terezin/Theresienstadt was turned into a ghetto for Jewish families. During the existence of the Protectorate the Jewish population of Bohemia and Moravia was virtually annihilated. After World War II the pre-1938 boundaries were restored, and most of the German-speaking population was expelled.

[8] Yellow star in Slovakia: On 18th September 1941 an order passed by the Slovakian Minister of the Interior required all Jews to wear a clearly visible yellow star, at least 6 cm in diameter, on the left side of their clothing. After 20th October 1941 only stars issued by the Jewish Center were permitted. Children under the age of six, Jews married to non-Jews and their children if not of Jewish religion, were exempt, as well as those who had converted before 10th September 1941. Further exemptions were given to Jews who filled certain posts (civil servants, industrial executives, leaders of institutions and funds) and to those receiving reprieve from the state president. Exempted Jews were certified at the relevant constabulary authority. The order was valid from 22nd September 1941.

[9] Slovak Uprising: At Christmas 1943 the Slovak National Council was formed, consisting of various oppositional groups (communists, social democrats, agrarians etc.). Their aim was to fight the Slovak fascist state. The uprising broke out in Banska Bystrica, central Slovakia, on 29th August 1944. On 18th October the Germans launched an offensive. A large part of the regular Slovak army joined the uprising and the Soviet Army also joined in. Nevertheless the Germans put down the riot and occupied Banska Bystrica on 27th October, but weren't able to stop the partisan activities. As the Soviet army was drawing closer many of the Slovak partisans joined them in Eastern Slovakia under either Soviet or Slovak command.

[10] KGB: The KGB or Committee for State Security was the main Soviet external security and intelligence agency, as well as the main secret police agency from 1954 to 1991.

[11] Gulag: The Soviet system of forced labor camps in the remote regions of Siberia and the Far North, which was first established in 1919. However, it was not until the early 1930s that there was a significant number of inmates in the camps. By 1934 the Gulag, or the Main Directorate for Corrective Labor Camps, then under the Cheka's successor organization the NKVD, had several million inmates. The prisoners included murderers, thieves, and other common criminals, along with political and religious dissenters. The Gulag camps made significant contributions to the Soviet economy during the rule of Stalin. Conditions in the camps were extremely harsh. After Stalin died in 1953, the population of the camps was reduced significantly, and conditions for the inmates improved somewhat.

[12] Solzhenitsyn, Alexander (1918-2008): Russian novelist and publicist. He spent eight years in prisons and labor camps, and three more years in enforced exile. After the publication of a collection of his short stories in 1963, he was denied further official publication of his work, and so he circulated them clandestinely, in samizdat publications, and published them abroad. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1970 and was exiled from the Soviet Union in 1974 after publishing his famous book, The Gulag Archipelago, in which he describes Soviet labor camps.

[13] Residence permit: The Soviet authorities restricted freedom of travel within the USSR through the residence permit and kept everybody's whereabouts under control. Every individual in the USSR needed residential registration; this was a stamp in the passport giving the permanent address of the individual. It was impossible to find a job, or even to travel within the country, without such a stamp. In order to register at somebody else's apartment one had to be a close relative and if each resident of the apartment had at least 8 square meters to themselves.

[14] Subcarpathia (also known as Ruthenia, Russian and Ukrainian name Zakarpatie): Region situated on the border of the Carpathian Mountains with the Middle Danube lowland. The regional capitals are Uzhhorod, Berehovo, Mukachevo, Khust. It belonged to the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy until World War I; and the Saint-Germain convention declared its annexation to Czechoslovakia in 1919. It is impossible to give exact historical statistics of the language and ethnic groups living in this geographical unit: the largest groups in the interwar period were Hungarians, Rusyns, Russians, Ukrainians, Czech and Slovaks. In addition there was also a considerable Jewish and Gypsy population. In accordance with the first Vienna Decision of 1938, the area of Subcarpathia mainly inhabited by Hungarians was ceded to Hungary. The rest of the region was proclaimed a new state called Carpathian Ukraine in 1939, with Khust as its capital, but it only existed for four and a half months, and was occupied by Hungary in March 1939. Subcarpathia was taken over by Soviet troops and local guerrillas in 1944. In 1945, Czechoslovakia ceded the area to the USSR and it gained the name Carpatho-Ukraine. The region became part of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1945. When Ukraine became independent in 1991, the region became an administrative region under the name of Transcarpathia.

[15] Iron Curtain: A term popularized by Sir Winston Churchill in a speech in 1946. He used it to designate the Soviet Union's consolidation of its grip over Eastern Europe. The phrase denoted the separation of East and West during the Cold War, which placed the totalitarian states of the Soviet bloc behind an 'Iron Curtain'. The fall of the Iron Curtain corresponds to the period of perestroika in the former Soviet Union, the reunification of Germany, and the democratization of Eastern Europe beginning in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

[16] Khrushchev, Nikita (1894-1971): Soviet communist leader. After Stalin's death in 1953, he became first secretary of the Central Committee, in effect the head of the Communist Party of the USSR. In 1956, during the 20th Party Congress, Khrushchev took an unprecedented step and denounced Stalin and his methods. He was deposed as premier and party head in October 1964. In 1966 he was dropped from the Party's Central Committee.

[17] Twentieth Party Congress: At the Twentieth Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1956 Khrushchev publicly debunked the cult of Stalin and lifted the veil of secrecy from what had happened in the USSR during Stalin's leadership.

[18] Beriya, L. P. (1899-1953): Communist politician, one of the main organizers of the mass arrests and political persecution between the 1930s and the early 1950s. Minister of Internal Affairs, 1938-1953. In 1953 he was expelled from the Communist Party and sentenced to death by the Supreme Court of the USSR.

[19] Rehabilitation in the Soviet Union: Many people who had been arrested, disappeared or killed during the Stalinist era were rehabilitated after the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1956, where Khrushchev publicly debunked the cult of Stalin and lifted the veil of secrecy from what had happened in the USSR during Stalin's leadership. It was only after the official rehabilitation that people learnt for the first time what had happened to their relatives as information on arrested people had not been disclosed before.

[20] Perestroika (Russian for restructuring): Soviet economic and social policy of the late 1980s, associated with the name of Soviet politician Mikhail Gorbachev. The term designated the attempts to transform the stagnant, inefficient command economy of the Soviet Union into a decentralized, market-oriented economy. Industrial managers and local government and party officials were granted greater autonomy, and open elections were introduced in an attempt to democratize the Communist Party organization. By 1991, perestroika was declining and was soon eclipsed by the dissolution of the USSR.

[21] Hesed: Meaning care and mercy in Hebrew, Hesed stands for the charity organization founded by Amos Avgar in the early 20th century. Supported by Claims Conference and Joint Hesed helps for Jews in need to have a decent life despite hard economic conditions and encourages development of their self-identity. Hesed provides a number of services aimed at supporting the needs of all, and particularly elderly members of the society. The major social services include: work in the center facilities (information, advertisement of the center activities, foreign ties and free lease of medical equipment); services at homes (care and help at home, food products delivery, delivery of hot meals, minor repairs); work in the community (clubs, meals together, day-time polyclinic, medical and legal consultations); service for volunteers (training programs). The Hesed centers have inspired a real revolution in the Jewish life in the FSU countries. People have seen and sensed the rebirth of the Jewish traditions of humanism. Currently over eighty Hesed centers exist in the FSU countries. Their activities cover the Jewish population of over eight hundred settlements.