Klara Karpati

Budapest

Hungary

Interviewer: Dora Sardi and Eszter Andor

Family background

Growing up

During the War

After the War

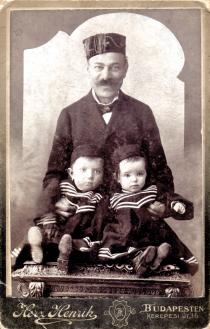

My father, Herman Grunberg, is of Polish origin. His mother, Berta Grunberg, lived in Poland. Grandfather Grunberg and my grandmother were cousins. I did not know my grandfather. He had a yeshiva in Poland, and was a teacher. In 1928-30 my parents and I went to visit my grandmother, who was living in Nowy Targ. This was a very interesting experience. My father had been looking forward to this trip very much. There were great expectations, because my grandparents were very observant Jews. My grandmother wore the sheytl, a traditional wig worn by religious married women. My poor mother and I found some of the traditions strange; for instance, in my grandparents’ home it was forbidden for us even to wash our hands with soap on Saturdays. My mother secretly discussed this with me, saying that she did not really like it, but we would have to adapt ourselves to those customs. There was a very vivid Jewish life in my paternal grandparents’ home. They had fantastic traditions. On Fridays there was such cooking and baking, and everyone down to the twenty-sixth neighbour participated. They cooked, they baked, and they kneaded. On Saturday mornings they went to synagogue, and afterwards a lot of people came to the house and were treated well. There were small cookies and drinks for the guests, who continued coming through the afternoon. I don't know how my grandparents paid for all that, because it didn't seem to me that they were well off. And money was conspicuous, because on Saturdays the beggars usually came around. None of them ever took two of anything; each of them took only one. My father had a sister named Elza whose husband was an upholsterer. The couple lived there with my grandmother. Elza’s husband was permitted to work only in the garden, because his work created a lot of dust and dirt. The entrance to the house was directly on the street. Above the door there was a bell which rang whenever anyone went in. Of course, it did not ring on Saturdays.

My maternal grandfather was named Adolf Neu. I did not know him, but I know that he must have been a man of progressive thinking, because he educated my mother. My mother was a diamond cutter. I knew my mother’s mother, Borbala Neu (maiden name – Kraut), as she was living with us when I was a little girl. She died in our house in 1922, when she must have been around 90. According to my mother, she never, ever took any kind of medicine. It was a waste of time calling the doctor to come out to see her, as she poured out the medicines he prescribed and threw away the tablets.

There were many children in my mother's family. Mother had a younger brother, Bela Neu, who killed himself. She also had a younger sister, who got married. They obtained very good information about the husband - it seems that it was fashionable at that time to get information about the intended. The only thing that was never mentioned was that he had TB. He infected his entire family: the children and his wife, and they all died. My mother also had another sibling who emigrated to America and was never heard of again.

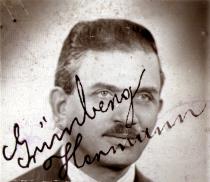

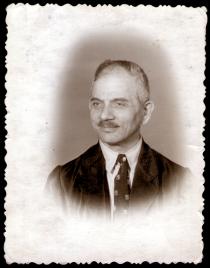

My father, Herman Grunberg, was born in 1887. He was seven years younger than my mother. His birth name was Hirsh-Leid Grunberg. He wanted to “magyarize” his name and went to the ministry repeatedly until he was finally given permission to change it. This could have been around 1926-27.

My father told me that in his childhood he joined the fair, which came to Hungary, too. My father’s sister, Elza, also went along. She had a folding stall and on fair days she displayed her wares. She sold mostly articles of clothing for women: jumpers, cardigans and the like. I do not know when my father came to Hungary. I do know that in 1912, when he married my mother, he had already been here in Hungary for some years. He spoke pretty good Hungarian. Maybe here and there he had a little accent, which showed that Hungarian was not his mother tongue. I can remember that he counted in Yiddish.

Father worked for the neolog Jewish community, as a sort of secretary under the chief secretary. For many years there was a very famous secretary at the community, Sandor Epler, whom my father liked a lot. He was kept quite busy, because Epler was a workaholic. He worked late into the night on many occasions, and my father did the same.

My mother, Karolina Grunberger (maiden name – Neu) was born in Budapest in 1880. She married quite late, in 1912. Her pregnancies were difficult. There should have been seven siblings, but only I was born, and then a girl after me, who died when very young.

We lived at 11 Istvan Street in a very simple flat, but I don't remember it well. When I was about four or five, my father got another flat from the community on Sebestyen Rumbach Street, in the same house as the synagogue. Only employees of the community lived there. There was quite a big kitchen and main room, and a sort of larder in the internal corridor. We redecorated the kitchen and turned it into a bathroom, and turned the larder into a kitchen. My mother very much liked the old bedroom furniture: the two big beds, two bedside tables, and the dressing-table. The furniture was beautiful. In the kitchen there was an old fashioned item of furniture which had an upper part and a lower part and at the back of it we kept the mortar and things of that kind.

My mother did not work outside the home. She stayed at home, managed the household, cooked and did the shopping. We went to Klauzal Square to the market to shop for food. Mother usually took me along with her. There in Klauzal Square was the goose-merchant she always bought from. Mother kept a kind of kosher kitchen. We bought butchered geese from the Klauzal Square market, and we kept dairy goods and meat items separate. My mother made cracklings and liver from the geese and all sorts of other goodies. My mother was an excellent cook and baker. She baked many kindlies, baby shaped cookies stuffed with nuts and poppy seeds, for Purim, and my father's work-mates told him to tell “Karolinka” to send more.

My mother did not attend synagogue much, nor did my father, even though he came from a relatively observant family. He went to synagogue during the festivals; he owed that much to the community. My mother lit a candle on Friday evenings. We had meat soup on Fridays and on a plate beside it, there was black radish, tomato sauce, and this or that kind of sauce with meat and challah. My mother did not make the challah; we bought it. I remember that my father used to do kiddush with a glass of wine. (Editor’s note: Kiddush is the ritual consecrating the Sabbath and the festivals. It is done with wine at the synagogue and with wine and challah at home.)

We used to celebrate the Seder Eve; my father kept a beautiful Seder. He used to put on the kitl (the death robe), as he kept the Seder in that. The prayer came first, and then between two prayers we had the dinner: meat soup with matzoh dumplings. Seder Eve was long, because the prayer is quite long, and we had to say everything down to the last song. My father sang a lot. There were one or two guests whom my father or my mother invited, but mostly we were on our own. We did the cleaning before Pesach, but not thoroughly enough to sweep up absolutely everything, the way one ought to do. My mother had a special Pesach pot.

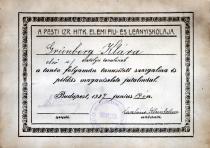

I attended the Jewish school at 44 Wesselenyi Street until the third grade primary and secondary school. I was taught well at the school. There were courses in the Hebrew language and literature. We studied the Bible and prayer books, and learned various songs, and prayers. We also did translations and we had to know all sorts of things, but after finishing school we didn't have to deal with those subjects further.

Parties were very fashionable back then. My mother had a good relationship with the other parents, so I was invited to many parties. I had only Jewish friends. Circumstances worked towards my having a Jewish circle around me: my father worked for the community, we lived in the synagogue building in Rumbach Sebestyen Street, and I attended the Jewish school. In the afternoons I studied; sometimes a girlfriend would come over, and we would pass the afternoon studying together. We read a lot. My mother loved books. I went to the library with my stepsister, Rozsa. We always discussed who would go to the library. She liked reading, just like me.

I had a girlfriend, who went every year to Domsod, and we went, too, with my mother, once or twice. We rented a room at the inn. There were quite a number of children there and we had a great time.

At home, we lived on the same floor with the shamash (the synagogue servant). He had a daughter, and a seamstress used to come to their house all the time to make her clothes. Whenever we needed something made, my mother would ask them to let her know that we wanted the seamstress to come to us too. My mother insisted on my being well-dressed, and there was a shop in Kiraly Street where dresses for young girls could be found. We usually went there for clothes.

I was twelve or thirteen when my mother died and my father and I were left alone. I could not bear the loneliness, and it often happened that I went to the community office where my father worked, and lay down there, and he had to take me home half-asleep. It was not good, because my dear mother had spoiled me an awful lot, and I missed her. When I was fourteen, my father married again. His second wife, Matild Rosner, was a very observant Jewish woman who started teaching me to be more observant as well. Matild was a widow with two children: Rozsa and Laszlo Rosner. The boy was one or two years my senior and the girl was younger. Matild had two brothers in Paris, and one of them who was a furrier took the boy in and taught him the fur trade. Rozsa went to school here. Later she went on to university, but her studies were interrupted by the war. Matild tended to the household. She had owned an underwear-sewing shop during her widowhood, and she went on working there. There were richer Jews who made real trousseaus for their daughters. She had some women from the provinces who did the embroidery for her, very beautifully.

After secondary school I attended the Jewish commercial school on Bethlen Square, where I completed a year of commercial studies. We learned shorthand, typing and bookkeeping there, too. At first, I first worked at the office of a lawyer, who was an acquaintance of my father. Later, I got into a glass and china store, working in the office there as well. I did the invoices, and had to do a lot of other things.

My first husband, Laszlo Schachter was born in Budapest in 1909. He was much older than I. I met him while working at a company that was a commercial agency in toiletries and represented several foreign companies. My boss was a Jew, and I was a shop manager there. I went around the perfume shops in Budapest. There were people who worked in the provinces too. They were called agents. One of them was the elder brother of my second husband. Laszlo, my first husband, also went to the provinces. There were seven children in his family, five boys and two girls. I was friendly with the girls and with four of the boys. We used to go out together on outings to Harmashatar Hill, but the boy who later became my husband and I didn’t really know each other. Then the elder of the two girls thought that it would be nice to organize a date for Laszlo and me to get to know each other better. They organized a date for us at the Astoria hotel, a posh hotel of that time. Well, this resulted in an unbelievable love. In 1942 we had our wedding in the synagogue in Rumbach Sebestyen Street.

Laszlo’s family lived in a two-room flat on Terez Street. They had come from Felvidek (in Slovakia today) and the brother who worked at the company as an agent had brought them to Pest when the circus problems started. As the eldest sibling, he helped the others. They were very observant. Every Friday evening, my father-in-law with his five sons attended the synagogue in Rumbach Sebestyen Street. I did not wear a sheytl, but I always bought kosher meat. As we had a small, bright, new flat, we had no difficulty keeping a kosher kitchen.

After the wedding we went to look for a flat. On Hungaria Street and Stefania Alley four- and five-story houses were growing like mushrooms. And there were lots of signs indicating flats for sale. We liked one of the flats very much and paid the advance for it. It was a charming little flat. There was a main room, a kitchen with a French balcony, a hall, a larder, a bathroom and an indoor toilet.

We were married in 1942, and then there came the labor conscription, so we could not settle properly in our flat. My poor husband was serving in military camps by then. When visits were permitted, I went to visit him. Then we found out that I was pregnant. He was stationed in Sarospatak, and I told him that I would not leave until he told me that I could keep the child. Then he was sent out to Transylvania, and I went there, too. When Laszlo returned, he got a paper giving him permission to sleep in his own flat because of the lack of space in the barracks. There was a raid on the house in the autumn of 1944, and despite his paper, Laszlo was taken away, and sent out of the country for forced labor, but I don't know where. He never came back.

My son Istvan was born in January 1944. His Jewish name was Shmuel ben Avrohom Yantev. I had an argument with my mother-in-law over his name, because she wanted to chose the Jewish name of the child, despite the fact this was the mother's right. The argument was about whose grandfather's name the child should have, mine or hers; when we realized that both grandfathers had the same name, Shmuel, the argument ended. My husband was still able to see his son, but after he was taken away, every Friday evening and Saturday for lunch I was at my mother-in-law's. She expected me to be there. I was still living with our child on Hungaria Street, but later I was moved to town, to the home of my husband's eldest brother, Erno Schachter. His “magyarized” name was Sandor, changed after the war. He was living on Terez Street, as were his parents. I lived alone in that flat with my son, because Erno had a business with a proxy. (Editor’s note: In 1944, when Aryanization started and Jews were not allowed to own shops any more, many Jews handed over their businesses to Christians for the sake of the documents, and worked behind this facade.) This proxy was quite wealthy and Erno with his wife and his little daughter moved there. The proxy was hiding them.

Then it happened that the house on Terez Street became a yellow-star house. Then one day, the Arrow-Cross men came, and ordered everyone to take their luggage into the yard. In the house there was a hairdresser’s shop and the lady owner told me, “If you want, I'll help you.” I collected a pile of diapers and put them in my son’s big pram along with some other things I thought we might need, and that woman took me out of the house. I went to the house of the woman who was hiding my brother-in-law.

My father, his wife Matild and daughter Rozsa were in the cloth-gathering battalion in the Jewish Gymnasium. Matild’s son, Laszlo, was expelled from France as he was not a French citizen. He came home and was taken into forced labor somewhere in the Ukraine. He did not return. After the war my father and Matild could not go back to their old flat because the staircase had fallen down, and they were offered a shared flat. My father said that he would not go to any shared flat, that he had another house in the province and he would go and live there. This house was in Gyomro, close to Pest. It was a nice, detached house which my father and Matild had built, and in which they had lived before the war from spring until autumn. Matild was a very skilled woman, she knew how to work in the garden, too; it was she who told my father what had to be done there. They ran a kosher household and every Thursday Matild came to Pest to have the poultry killed by the schochet (the kosher butcher) and toget beef. There was a nice little synagogue in Gyomro, and father attended services there. Every morning he prayed in tefillin (phylacteries).

Rozsa met a boy in the cloth-gathering battalion who married her not long after the war, and they had a daughter named Jutka. This little girl was also in Gyomro, as Rozsa restarted university. The poor dear; she often fell asleep at the table in the evening, as she wanted to finish her studies at all costs. She became a teacher. In 1956 they emigrated to Canada. They had one more son there. In 1957-58 Matild, together with my father, emigrated to Canada, too. We were on good terms with Matild; I visited her in Vancouver. She was crying when I left, because we knew that we would not see each other again. My father died in the 1960s-70s; Matild died a few years ago. She lived to be nearly a hundred years old. (Editor’s note: The interviewee does not remember it well; it is more likely that Matild died at the end of the 80s.)

When Pest was liberated, I went to find out what had happened to the flat in Rumbach Sebestyen Street. I ended up going to live at my father’s place in Gyomro with my child. One of my sisters-in-law had a shoelace plant there. She asked me if I wanted to work there. "You could make shoelaces," she said. I told her that I wanted to work, so I went to work producing her shoelaces.

I waited for my husband to return for a long time. Finally, my mother-in-law told me that since I was young, I should remarry. How old was I then, twenty-four or twenty-five? Of course, my son also missed having a father. My second husband, Aron Karpati, was from Pesterzsebet. My step-sister Rozsa, who was working in a sports shop in Pest at that time, had a friend who was from Pesterzsebet. The two friends talked it over and decided that they should bring Aron Karpati and me together. The wedding took place in Sip Street at the rabbi’s. My second husband’s original name was Aron Kraus, which he “magyarized” in 1948 to Karpati. He worked with leather, and before the war had worked in Paulay Ede Street, which in those times was the street of the leather workers. Aron made quite a good living. In Russia during the war the men were taken into forced labor. They were gathered together and asked who could make harnesses. Aron said that he could, so they sent him to a plant and he made harnesses there until he came home. After the war, he worked in a ready-to-wear leather factory in Rakospalota. He was the manager of the finished product store.

He was not observant. The place, Soltvadkert, and the family he came from, was observant. But he had left home quite young, lived in a rented room in Pest, and hadn't stuck to his religion. He didn't like going to synagogue. On Fridays, I still lit a candle. And there was the Friday evening supper, even though it was not like at home. On high holidays we went to synagogue and Aron came along, too, and there was fasting at Yom Kippur. Later, when Aron became ill, he gave up fasting. To this day I do not cook on Saturdays. And I do not cook pork, or use pork fat. I cook with oil or goose fat instead. I also do not eat meat with vegetable dishes that have sour cream as an ingredient. My son has a lot of Jewish feeling in him, as do his children. They go to Szarvas, the Lauder Camp. I reared my daughter in this Jewish atmosphere too, but seemingly, it did not get deeply into her. I might be the cause of this, because when she was small she told me that as we had neither Hannukah nor Christmas, she did not know either of those holidays.

My first husband’s elder brother did not want to let me work. He was always pestering me, saying, “What do you intend to do with the child?” He helped me out financially, but still I wanted to work.

Finally, I went to work for the Buda Jewish community, doing office work. The taxes for the Jewish community were gathered as ordinary community taxes. There were still some wealthy Jews in Buda. The local board had information about the taxpayers’ incomes. We set up a committee and invited the taxpayers to a meeting, where we told them that their taxes would be lowered if they paid them on the spot. There were some who put the money on the table right then and there. There were quite a lot of things to spend the money on. There was a kitchen where the employees got lunch, and there was an office, and there were Jewish graveyards in Buda. When the community of Buda and that of Pest were combined, I was working at the Audit Office. Later, I went to work for the management of the housing estate. When my daughter Agnes-Gabriella was born in 1953, I resigned. One of my sisters-in-law was working at a construction company, and the company gave me project documentation to type at home. While I typed, my daughter knew that she was not allowed to talk to me. My husband and I agreed that he would take her to the park when he finished work; it started quite early, so he was home by three, and he would buy everything I needed. By nine or ten o'clock I had lunch ready, and then I started typing.

In 1971 I retired from “The Culture,” a company that dealt with books, newspapers, records, didactic materials and such. I was an assistant executive in the book department. We sent books to East Germany. The assistant executive was the right hand of the dealer. The dealer made the deals and the assistant executive executed the transactions. There were quite a lot of Jews working there, even in management. The director was also a Jew. My boss was a Jewish woman. I always told her that I wanted to take my holidays at the time of the autumn festivals.

My daughter, Agnes-Gabriella, graduated from the college for foreign trade. At first she worked at the Metrimpex, then at the Konzumex (state owned export/import companies) She left when they were still able to give severance pay. Since then she has worked at different companies with limited responsibility.

In 1956 we nearly emigrated to Israel. My husband had a sister named Margit, who was deported to Auschwitz during the war, along with my husband’s mother and his sister’s daughter. His mother and the little girl were sent to the gas chambers, and my sister-in-law to work. After the war, she established a new family and emigrated with them to Israel. We wanted to go with her. Her family were able to get passports, but ours could not. It was awful having to stay behind. In Israel, mMy sister-in-law’s family arrived at some rudimentary houses in a desert where it was very warm. After their arrival, they wrote that they wanted to come back.

My husband and I visited Israel once. There were no diplomatic relationships then, so I did not know which embassy would allow us to go. In Israel, I saw that there was hatred where there should have been none. A Jew should simply be a Jew, and there should be no discrimination because one person is from Europe, and another from somewhere else. I do not like this.

We have many relatives in Israel. The relationship between my son and his father’s relatives is quite good. They love their granddaughter, Judit, who went to university there.