Helena Kovanicova

Prague

Czech Republic

Interviewer: Terezie Holmerova

Date of interview: February 2006

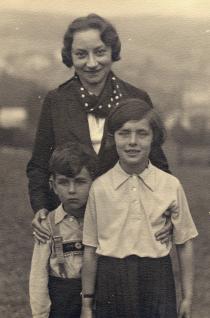

At first I was only supposed to interview Mrs. Kovanicova's brother, Jiri Munk, but it ended up completely differently. For our first work-related meeting, Mr. Munk had prepared a pleasant surprise for me. Right after crossing the threshold, I was informed that his sister had come to have a look, but that she won't want to talk with me very much, that she'll more likely just sit quietly and 'will occasionally add something.' My expectations of a frowning, nervous lady were quickly dispelled. Mrs. Kovanicova was silent for only a little while, for a while she and her brother complemented each other, for a while they chaffed each other endearingly, and in short order Mrs. Kovanicova took the helm completely. So it was decided, and thanks to this each of the siblings has their own biography on this website. I grew very fond of the elderly lady. She always greeted me warmly and with a smile. When she told her story, she laughed, cried, one time she was for me a young girl who sang for herself in Terezin 1, another time again an adult woman, who despite all obstacles decided to help her family during the difficult post-war years. Because she liked remembering old times, the focus of our interview lies in the pre-war period. I won't say any more, as the following speaks for itself.

Family background

Growing up

During the War

After the War

Glossary

I didn't find out much about my oldest ancestors. Our parents weren't particularly communicative, and what's more, my and my brothers' home environment was very strict, so we didn't even dare ask our parents much of anything. Maybe if the war wouldn't have come and we could have grown up normally, perhaps we would have found out something. But with the war came nothing but worries, nothing but prohibitions and regulations 2, and neither was anyone in the mood after the war to talk about the history of our family, especially since our father died in 1944 in the gas chamber in Auschwitz.

My relatives on my father's side came from the region around the Labe River. My father's father was named Eduard Munk and he lived with his wife, Paulina Munkova, nee Gläsnerova, in Privory, near Vsetaty. My father had two siblings, Bedriska and Josef. They also married two siblings, Aunt Bedriska married Mr. Vilem Vohryzek, and Uncle Pepa [Josef] married his sister, Marta Vohryzkova.

My father's siblings lived with their families in Doubravice, not far from Teplice, where they had a large farming estate. Vilem and Bedriska Vohryzek lived right on the estate, which was surrounded by walls and locked gates. At night a night watchman with a German shepherd used to walk around it. The dog was a female, named Asina, and was terribly vicious. The farmyard included a hayloft, barn, pigsty, blacksmith's shop, dairy and other buildings. Outside of the farmyard stood a single-story villa where Josef and Marta Munk lived. Their villa was surrounded by a tiny yard, and Asina was tied up in the back all day, because she was allowed to run free only at night. The entire estate stood isolated, off in the middle of fields, only one road, which led to Trnovy, passed near the Munks' house.

We used to go visit our relatives in Doubravice often, mainly at Christmas and in the summer. I especially liked Christmas in Doubravice. When there was snow, they would come get us from the train in a sleigh, it was beautiful. We observed traditional Christian customs, so I remember that in Doubravice at Christmas we'd pour lead or throw slippers. [Editor's note: Traditional Czech Christmas customs - molten lead is poured into water and according to the shape it takes, important future events in one's life are foretold, girls throw a slipper over their shoulders, and when the toe points towards the door, it means that they'll be married within a year.] When we arrived in the summer, Mr. Janda always came for us in the carriage, in the winter in a sleigh. Mr. Janda worked on the farm as a coachman. During World War I he fought with Uncle Pepa in Russia with the Czechoslovak Legion. When we would go to Doubravice to visit our relatives, we had to alternate between the two families. One year we'd stay with the Munks, the next with the Vohryzeks.

Aunt Bedriska was an excellent homemaker. She was a superb cook. Whenever we were there for Christmas, Auntie would make loads of Christmas cookies. Often in the summer she'd prepare a young roast goose, which I especially liked. My aunt had attended dairy school in Varnsdorf or someplace there near the border. Because Aunt Bedriska used to spend the entire morning on her feet, in the afternoon she liked to sit down in her favorite leather armchair and devoted herself to handiwork, she'd crochet these strips of short columns, from which she then created various ornaments and sewed them onto tulle. She was skilful, but maybe it was also because back then girls were brought up to do handicrafts, they embroidered monograms onto their trousseaus and so on.

Uncle Vohryzek lived only for his farm; he would get up at 5am and was already present at the first milking. Often it would happen that they'd come to the theater to get him, that a cow was giving birth, and he'd have to hurry home again. Because during our holidays in Doubravice the Vohryzeks would occasionally take our parents to the theater. Back then in Teplice there was, and still is, a theater with a café.

The Vohryzeks had two daughters, Hana and Helena. I hung out the most with Helena. She was two years older than I, and sometimes as a joke we'd pretend that we were sisters. They called us the Helkas. Some young woman also lived with the Vohryzeks, likely a nanny, and an adjunct and an articled clerk used to come there to eat. In two of the buildings lived peasants, who were usually Slovaks, who worked on the farm. They were given bread, flour, and I'm not sure whether also butter and milk.

I remember the tile stove in Doubravice, against which I would always sit during our Christmastime visits, because I was often cold. I remember my aunt hand-churning butter in the churn. Later she already had an electric one. The butter was chilled in a large pool in special forms, and would then be taken to Teplice for sale at 'Konzum.' For us children my aunt would make cocoa for breakfast, which we drank from large onion-patterned mugs. Back then onion-patterned porcelain services were used for normal daily use, and it wasn't as valuable as it is today. But we didn't like the cocoa very much, because it was made with fatty whole milk from the farm, and we were used to store-bought milk, which was, as they used to say, baptized with water.

Uncle Pepa Munk was a Legionnaire in Russia during World War I. He was this quiet person of few words. I always felt sorry for him, because I had the feeling that he wasn't overly happy in his marriage. In the family they used to say that Uncle Pepa and Aunt Marta were each completely different. My aunt was this outgoing person, while my uncle was more of a domestic type. My aunt was a very nice-looking lady, she always went about fixed up, with makeup on.

The Munks had a son, Jirka [Jiri], who was a year younger than I, and misbehaved terribly. He was like a sack full of snakes, they had no idea what to do with him. He'd for example run around the barn, lie under a cow and squeeze the milk directly into his mouth. He was often beaten.

I was occasionally afraid at the Munks'. Because we stayed on the ground floor, from out of which you could climb through the window, and the maid that was supposed to babysit us in the evening would always run off on some date and we'd be alone in the room with open windows, crying. The adjunct had a room upstairs. Right before the war Aunt Marta was pregnant, and they had a baby girl. Uncle Pepa was apparently very happy, but unfortunately the little girl soon died.

The farm also had a 'plummery,' which was a large fruit orchard. I remember that as children we'd go there with Marenka from Chrast, our maid, to pick fruit, and some watchman chased us out of there, hooking us by the neck with his cane. We were always all jumpy because of it. Another memory I have is how sometime at Christmastime before the war our cousin lent us some ski clothing and children's skis. We tried skiing, but weren't very good at it. Then came the war, and the fun was over.

Our ancestors on my mother's side were mostly from Prague. My mother's father, Rudolf Nachod, born in 1858, was a lawyer. My mother's mother, Hermina, nee Eisenschimmelova, died very early on, likely of cancer, she wasn't even 40 years old. My mother, Olga, had two siblings, Elsa and Quido. They lived in the Smichov quarter of Prague, on Fibichova Street, which today is named Matousova. After their mother Hermina died, their grandmother, Aloisie Eisenschimmelova, brought them up. She lived in the Zizkov quarter and every day she walked all the way to Smichov to be with her grandchildren. My mother told me that Grandma Eisenschimmelova had separate dishes for meat and dairy foods, so probably was the only one in our family to still maintain Jewish customs. She was also very strict.

My mother's brother Quido was born in 1894. He was the oldest of the three siblings. As a little boy he was very bad. Even later, as an adult, he was rather on the unstable side. At first he worked at some bank, but he didn't last long there, which otherwise he didn't anywhere he worked either. I think that his last job was as a controller for the Perla department store in Prague. On the other hand, he was a very meticulous person. He took great care of his appearance. He was for example capable of altering or repairing his own clothes.

He married Bedriska Adamkova, who wasn't of Jewish origin. My mother didn't like her very much; she'd occasionally drop hints that her past wasn't the best. My aunt was the type who'd kiss everyone, including the doctor. My uncle would always call her 'sweetie' and she'd call him 'sweetum.' They didn't have children, but my aunt once said that she could have had a child, but that she and her husband were afraid that they wouldn't be able to support it. I don't think, however, that they lived badly, and what's more, for a long time my father paid them rent. At the end of the war, in 1945, my uncle spent about a month in Terezin, because only then did Jews from mixed marriages arrive in Terezin. Aunt Bedriska died in 1971, Uncle Quido about two or three years after her.

Aunt Elsa Nachodova was born in 1899. In adulthood she lived in Prague at 4 Anglicka Street, where she had her own apartment, beautifully furnished with antique furniture. It was made up of two rooms, a kitchen and a small servants' room. In her apartment from the front hall one first entered the dining room where my aunt had old furniture and a tall sideboard, a large table and chairs. In her bedroom she had modern furniture that had been custom-made to the dimensions of the room. There was a wardrobe, two couches, between them a small bureau, plus a low table with a glass top and beside it two armchairs. On the glass table she used to have a bowl with a string of pearls.

Elsa had to support herself, and that's why she made a living teaching foreign languages. She gave private lessons in her apartment, as well as at the language school in Ve Smeckach [Street]. For a long time she was single, and in the end she married some Mr. Grund. He was, however, a fraudster, he robbed her and fleeced her of all her modest savings. He was from Vienna, and claimed that he was a 'von' [i.e. from a noble family]. Later Elsa married for a second time, Mr. Erich Ederer, who worked as a traveling salesman and was very kind. Once at Pentecost my aunt and Mr. Ederer took me on a trip to Karlovy Vary 3. Mr. Ederer had many friends there, together we went to many nice pubs, they ordered me cocoa and scrambled eggs for breakfast, which I wasn't used to. They also took me to a variety show. They were both very kind to me. Once during the school year my aunt even wanted to take me somewhere abroad, but my father was strict and didn't allow me to go, because I would have missed school.

I liked Auntie Elsa the best of all my mother's and father's siblings. Auntie didn't have any children, and I think that she also liked me very much. I very much liked going to visit her. The first time I went to visit her was for Easter, when I was eight, and I stayed with her for a whole week. She bought me a little calendar, and there she wrote down where we had been together. We for example went for ice cream to Berger's, which was a popular confectionery on Vodickova Street. It was like a holiday for me, because at home we weren't allowed ice cream. When I was coming back from my aunt's for the first time, my mother came to get me. I remember that I cried on the bus the whole way, because I didn't want to go home.

My aunt was a real fashion plate. She was always perfectly dressed, even despite the fact that she had to buy it all herself. When I visited her, she took me everywhere with her, and so I know that she'd for example go to the luxurious 'Prokop a Cap' textile store on Wenceslaus Square, where she'd occasionally pick some textile from their samples, which they would then order for her from England, for example. I remember this store mainly because there was a neon stork above the entrance that would open and shut its beak. She had her shoes custom made by a renowned shoemaker on Na Prikope Street, across from Slovansky Dum [Slavic House]. Once a week she'd go with my uncle to the Luxor coffee shop to play bridge.

My mother, Olga Nachodova, was born in 1897 in Brandys nad Labem. She grew up in Smichov in Prague. My mother had some one-year German business school, and knew German shorthand perfectly. I've even got a diploma stored away someplace, where they write that she won some shorthand contest in Teplice-Sanov. This contest was organized by the Association of Gabelsberg Stenographers. She wrote down all recipes or even other notes in shorthand. She obviously also spoke German very well, because when as a young girl I was studying German and going for lessons, my mother would correct my homework and also used to tell me that I've got a Czech accent. Besides German she also spoke a bit of French, because when she was young she used to take French lessons from a lady who was a native French speaker.

In 1923 she married my father. I think that my mother wasn't very satisfied with her life. She was never employed, although she would have very much liked to be. In spite of being a good cook, and having no problem managing our household, she always claimed that she didn't like being a housewife. My mother would have liked to have had a job. She also very much wanted to travel. My mother and father unfortunately didn't have too many interests in common. When they went to Prague together on a Sunday, my mother would go to a coffee shop, most often to Café Alfa on Wenceslaus Square, where she had loads of friends, and my father would in the meantime go see some exhibitions by himself. What's more, my mother and father were somewhat different in terms of personality. While my father was calm and collected, my mother would often fly off the handle.

My father, Adolf Munk, was born in 1887 in Privory, near Vsetaty. He studied law. He was a rather quiet person, he was never too fond of socializing. Once someone told me that they used to have to force my father to go dancing with his sister. He was supposed to be her chaperone, but because he didn't like it, he tried to get out of it in all sorts of ways. Once at some dance he even rented himself a room, and instead of dancing he slept.

One of his favorite hobbies was painting. To this day in my diary I have a painting of this cute little house. In Doubravice he once painted a beautiful picture of a vase of dahlias. For a long time this painting then hung above my mother's and father's bed in Brandys, up to the time we were supposed to go to Terezin. Because back then our neighbors came over to collect what they could. They took our curtains, duvets and some other things, as well as my father's painting of the dahlias. Everyone hoped that we wouldn't return, and that they won't have to return anything.

My father also liked carpentry. He for example made me a round, white side- table, he made a stand for the radio and many other things. He set up his carpentry workshop in the laundry room. There he had cabinets with tools and a workbench, a so-called 'ponk.' For his birthday my mother would often buy him a plane or some other tool.

My father was extremely strict. He just needed to look at us strictly, and already we all knew that we shouldn't misbehave. But we were rarely actually spanked. I remember that I got it only once, and I don't even know for what any more. I liked my father very much, to tell the truth perhaps more than my mother. The only thing that I held against my father was when he forced my younger brother Viktor to eat cauliflower soup, which he hated. As soon as he'd finish it, he'd go throw up, and on top of it he'd then catch it from our father. For my part, I didn't like green peppers. Before the war we'd never seen them, but around the beginning of the war this type of pepper became available. I couldn't stand even their smell, and couldn't even walk by a widow through which you could smell peppers - right away I would get nauseous. My father forced me to eat them, just like my brother.

My father loved nature. Every evening at 6pm he'd close his office and go for a walk. He always said that he was going to go have a look at what the crops were going to be like. He didn't go via the town square, because he knew a lot of people in town, who would have constantly been stopping him, but took a back road across the fields in the direction of Zapy. Our mother also occasionally went with him, but it wasn't much fun for her.

My father also loved animals. He'd always wanted to be a veterinarian, but in the time of his youth there hadn't been any school in Bohemia where he could have studied this profession. Future veterinarians had to go to school in Vienna, which was too expensive for my father's parents.

I was born in 1924 in Prague, as the oldest of three siblings. Up until I was five or six years old, we lived in Prague in Smichov, on Fibichova Street [today Matousova] in an apartment that had belonged to my mother's parents. I don't remember much from this period. I think that we lived in a three-room apartment, and that it had a large dining room. The apartment was in an old multi-story building, on the ground floor was Mr. Sara's coffee store.

As a little girl as I had an ear infection, so probably my oldest memory is lying in some little room at our place in Smichov, and having a warm pillow put on my ear. Back then I hung out a bit with Alenka Gehorsamova, who was a pretty little blond girl roughly the same age as me. I found a photograph where we're together on a bench in the Dientzhofer Gardens near the Jirasek Bridge.

Sometime around 1929 we moved to Brandys nad Labem. My brother Viktor had already been born at that time, he was born in 1928. My youngest brother, Jirka [Jiri] was born in 1932. He was a very nice-looking child. Because he had caught some infection at the maternity ward, my mother brought home with her a children's nurse who took care of him. We all liked her very much. We called her Nanicka. She lovingly cared for my brother and stuffed him with food. Our entire family ate together at one large white round table, and when we were finished, little Jiri would get another wiener in the kitchen! Nanicka would also skim the skin off of milk, strain it through a sieve and add it to his Ovomaltine. Jiri was the best fed of all of us. I always said: 'For Pete's sake, he's fat as a pig!'

Nanicka wanted very much to send little Jiri's photo to some women's magazine, where proud mothers would send photos of their children, but my father wouldn't let her. Most certainly she thought that Jiri was the most beautiful child in the world. Once, when Jiri was misbehaving and was crying in his bed, my father wanted to spank him, but Nanicka protected him so fervently with her own body that she almost also got it instead. She was supposed to have been with us for six weeks, but it turned into eight years. I'm very sorry that after the war I didn't have her come live with me. Nanicka had diabetes and didn't eat properly. She always used way too much salt and pepper. She died in the hospital.

I didn't start going to school until we were in Brandys. At first I went to elementary school. There were two other Jewish children in my class, Bedrich Alter from Brandys, who had a younger brother, Pavel, and Vera Buchsbaumova, who commuted from Benatky nad Jizerou. Bedrich and Pavel Alter's father was a lawyer and his family were Zionists. Then in the same school was also Zdenek Stastny, a Jewish boy who was about a year younger than I, and two children from the Eisenschimmel family. The Stastny family had a hardware store in Brandys. Zdenek's father had been an Italian Legionnaire during World War I. As far as Jewish children go, there were also the two Weiss sisters from Kostelec nad Labem, whose family owned a drugstore there. In Brandys we had distant relatives, the Lustigs, who had a liqueur factory there. They lived in a beautiful one-story villa with a large garden, which was called the 'planta.' Some other Lustigs also lived there, who had a textile store.

I liked going to school. For the first two years we had Mrs. Magda Rezacova, after her Mrs. Simunkova. Both of them were very nice. When we finished 5th Grade, Mrs. Simunkova invited all of us students to her home and prepared refreshments for us. After I finished elementary school 4 I transferred to the state academic high school. Back then you didn't have to write an entrance exam, it was enough that I had good marks. Maybe Mrs. Rezacova was right when she told my parents to put me in family school. Back then people looked down on family school, they used to call it the 'dumpling house' or 'stocking house.' I think that it would have come in handy for me in life, because besides sewing, cooking and other practical things, girls also learned money management and some economics subjects.

In high school I had problems with math. While it was still just some ordinary multiplication or division, it wasn't a problem for me but as soon as we started on mathematical induction, I was at my wit's end. For math we had our homeroom teacher, Professor Zelinek. Later my father confessed to me that he'd never been very good at math either! And I had the same problem with physics as well. My grades from math and physics then began to mar my report card. On the other hand, I liked Czech, mainly spelling. My essays were always too short. Apparently I'm not very good at expressing myself.

In the first year we had Professor Halousek for Czech. All our older classmates felt sorry for us and told us that he was the terror of the high school. Mr. Professor Halousek was a bald man, who always had the laces of his underwear showing. Because back then men used to wear long white underwear. During class Mr. Professor would walk around the class the whole hour, thumbs hooked in his vest, and we were all afraid of him. When we wrote our first composition exercise, I think that it was some sort of book review, I was the only one to get an A. My parents probably then thought that they had some sort of miracle child at home, but later my composition results weren't as awe-inspiring, even though I usually did in the end get an A on my report card.

In the third year we got Mr. Professor Hlinovsky for Czech. He was a young person, a bit of a lummox. I had the feeling that he was from a poor family. He was another strange type. He'd sit at his desk, kick it with his feet, and fire off vulgarities to all sides. Professor Hlinovsky also taught us German. For our first German class with Mr. Hlinovsky I didn't learn any words ahead of time, because we'd heard that a new teacher was coming, and usually that meant that there wasn't any exam right off. But I was wrong. During the first class Mr. Professor Hlinovsky called me up to the blackboard, and because I didn't know anything, he told me that he'd test me during every class. It was terribly stressful for me. In the end I got a good grade from him.

I always liked geography, because we had an excellent teacher, Brumlikova. She knew how to talk about it in a very nice and interesting way. She used to commute from Prague to teach at our high school. She was supposed to be some distant relative of ours, I then met up with her in Terezin, where she secretly taught the children imprisoned there. On the other hand, I didn't like history at all. Our history teacher, Professor Cejnar, was a very nice, lenient man. Even I was so bold as to have my textbook in front of me in his class and read from it when he was testing me from my desk. The result was that I didn't learn anything about history, and I've still got big gaps.

I think that it wasn't until from fifth year onwards that a student in our high school could gain some more coherent, deeper knowledge and at that age also had a little more sense. Unfortunately I had to end my studies in the fourth year [Grade 9], because the Germans came and I wasn't allowed to go to school any more. I remember that our Czech professor, Hlinovsky, was at first surprised and didn't at all understand why I was leaving. Finally he told me that it was a shame to lose me, and that was the end of it. I had only one year of Latin, and neither did I manage much more in other subjects.

In Brandys my best friend was my classmate Anca Zakova. She lived a little ways away on the other side of the tracks and most often would come over to our place, where we played in the courtyard. Anca's father was a career soldier and her mother had died when she was about 14 years old. She had serious kidney problems. I remember that Anca and I were supposed to participate in the last high school track and field games before the war, which traditionally took place before the Vsesokolsky Slet [Sokol Games] 5, but she didn't come with me, because her mother had just died. Soon after that she moved with her father to Novy Bydzov, where Anca went to family school. There she learned to cook, sew, so then she was very handy and actually took care of the whole household for her father. In Bydzov she also apprenticed as a seamstress with some tailor. In the end she married someone from Tachov and lived in Tachov. I went there once to visit her.

Our house stood and still stands close to the town square in Brandys nad Labem. When you take the bus from Prague, it's the first house on the right with a front yard after you pass the railway crossing. I'm not completely sure who bought it way back when. It was either our father or my mother's father, who was also a lawyer. Our house was built on a slope, so facing the street it had two stories, but facing the garden it had one floor. Behind the house there was a courtyard and garden.

On the ground floor there were three rooms - my father's office, an articled clerk's office and a room for two clerks. Besides this there was also a small closet on the ground floor, which was called the archive because that's where my father stored his documents. On the first floor there was a long hall, four rooms, a kitchen and washroom. We children all shared one room, which was quite spacious, it had about 30 square meters. Because it was a really big room, we also had a large white round table, at which we all ate. On the floor there was cork linoleum, which was practical.

The room also had beautiful and back then modern dining room furniture with glass display cases, which covered a large part of a wall. I remember that when my parents bought this furniture and it was being moved into our house, it caused a huge commotion in Brandys. Displayed in the cases were various wine containers, water carafes and cut glass. I slept on the couch, my brother Viktor on a white bed, and the youngest, Jirka, had a little bed with netting, which would be raised at night so that he wouldn't fall out.

Besides three rooms on the upper floor, which looked out on the street, there was one more room on the same level that led out into the garden. Thanks to the slope it was on the ground floor, and didn't have very much light. Behind this room there was an extended roof, supported by columns, which formed a nice space where tiles had been laid down, there we had a table, bench, and two wicker armchairs. When we were small, we also had a little table and wicker chairs for children. All around grew clematis and Virginia creeper. In the summer we ate lunch and supper there, which I liked very much. The back part of the house also had a laundry, my father's workshop and a kitchen from which you could enter straight into the garden.

When we moved into the house, there were tile stoves everywhere. But my parents had them demolished, with the exception of one room where my brother Jirka and Nanicka slept, and which was heated only in the evening. Instead we heated with a so-called Musgrave stove, which back then were often used for heating in schools for example, which heated continuously and didn't go out, and heated all three rooms, if it was well stoked. We heated with coke and anthracite. But I was always frozen anyways. This was because my father never allowed the temperature to be higher than 18 degrees Celsius, and I've never been very hardy.

In the bathroom it was so cold you could even see your breath. There we had a tub and a high, round stove, which had to be fired up to heat the bathwater, so we bathed once a week. We did have a sink with running water, but only cold water. That's why in the morning Mother would always heat up some water on a petroleum stove, so as to warm up our washing a little. Despite that, though, I always shrieked when my mother washed my hair and poured lukewarm water from a white enameled kettle on my head, because I was always cold in that chilly bathroom. The bathroom also led into the courtyard.

My father made a darkroom out of one of the smaller rooms in the back part of the house, where he developed his own photographs. Often he'd send me to buy special photo paper. Back then there weren't too many electrical appliances, but despite that we had a radio and an old-style gramophone with a horn.

I couldn't stand milk, especially when it was warm, which is what our mother would give us at breakfast. She also bought so-called Ovomaltine. It was this strange cocoa with a mixture of malt and some other healthy things. We liked Ovomaltine, because when we sent a certain number of packages to some address, we got a fountain pen in return, which made us happy.

Across from our house stood a small house with a nice mansard roof that belonged to the builder Chlebecek. Beside this house was a very large garden, into which you couldn't see, as it was surrounded by a high wall. This garden stretched all the way to the Brandys railway station. In a niche in the wall across from our house was a tiny little chapel. Right by the road there was a linden tree, and under it a water pump.

Because there were six of us at home, my mother always had someone at home to help out. First Marenka from Chrast worked for us, who then got married, and in her place we had our maid Ema. Later, in 1938, when my mother didn't want anyone any more, we only had Mrs. Klouckova, who always came only to wash the dishes, do the major cleaning and at the same time took our laundry home to wash it. There was a Mrs. Krejcova who worked for my father, who would travel from Libise, near Neratovice. She had at one time worked for my mother's father. During the war we left some things with her, and as an honest person, she returned it all.

I didn't devote myself to sports very much. Although the yard of our high school had tennis courts, my parents never allowed me to play tennis, apparently because I was too skinny. I used to attend rhythmic gymnastics and occasionally went skating on the Sokol playground in Brandys, which they always flooded with water when it was freezing. We also sledded and played ping-pong, but that was all. I got relatively far in ping-pong, I think that I was really quite good. This was because during the war we weren't allowed to go anywhere, and so our father, because he was handy, at least made us a ping-pong table. We then would play all Saturday and Sunday, and later also during the week, we'd have various contests and I was always first or second. Sometimes, especially during the early evening in the summer, I even talked my father into it and we'd have a game of ping- pong together. Before the Germans occupied us 6, our mother used to go with us to the swimming pool, where I learned to swim, but I was afraid to go into the open Labe river, because once I had almost started to drown in it.

Between the wars there was a modern, newly built movie theater in Brandys. Unfortunately only those 16 or older were allowed to go. When I reached that age, then I wasn't allowed to go to the movies because I was Jewish. So I didn't get much out of the movie theater. I remember that I was at the movies once during summer holidays, I sat in the balcony. They were showing the film 'The Scarlet Pimpernel,' with the well-known actor Leslie Howard 7. I think that he fell as a pilot during the war. I remember sitting in the balcony and had no idea what was happening on the screen, and this is how I found out that I had bad eyesight and that I would have to wear glasses.

We never observed Jewish holidays very much. We'd go to synagogue with our mother only for the Jewish New Year [Rosh Hashanah]. The next day the so- called Long Day [Yom Kippur] is observed, when prayers for the dead are held. That day Jews are supposed to fast and carry an apple spiked with cloves with them to synagogue, which you sniff when you feel weak. But we never fasted.

Sometimes we also went to synagogue for the Chanukkah holiday. I remember that back then we children put on a little performance in the synagogue, we each had a candle in one hand and a flag in the other, and sang the song Maoz Tsur. [Editor's note: During the lighting of the Chanukkah candles, after the recitation of the appropriate blessing, two songs are sung - Hanerot Halalu (These Candles) and Maoz Tsur (Rock of Ages).] At the end we'd get a bag of candy for it. It was during the period before the Christian Christmas.

My father attended synagogue every Friday, because the service could only start if at least ten people gathered [for the so-called minyan]. So they would always meet there on Friday, but I've got the feeling that they more likely sat and told each other jokes there. Most likely it wasn't any sort of strict or official ceremony. I remember that as a child I always liked that synagogue's ceiling, which was blue with stars, just like the sky.

In our family we celebrated typical Christian holidays. Children used to tell on us to the rabbi, that we've got a Christmas tree. I always loved and to this day love a Christmas tree, and also like going to Christian churches. Up until the war I wasn't particularly conscious of my Jewish origins. During the whole prewar period, up until the time the Germans came, I didn't feel any anti-Semitism. Only at the beginning of the school year, when the teachers were writing down our religion in their class register, I always felt terribly awkward, I don't know why. I'd stand there, all stiff, along with Bedrich Alter, and would be embarrassed.

Similarly, when we went to synagogue for the so-called Long Day, after the Jewish New Year, we had to walk along the main street that led across the Brandys town square, and I wished I could have disappeared from the face of the earth. Because people were coming out of stores, and looking at that parade of ours curiously. My brother Viktor and I were always dressed up to the nines, we'd be wearing dark blue jackets with gold buttons and velvet collars from Hirsch [children's clothing] and a dark blue sailor's cap with ribbons in the back.

For some time before the war I used to go to religion lessons in Brandys. Brandys didn't have its own rabbi, and so Rabbi Mandl from Prague used to go there. There'd always have to be at least ten children, otherwise it wouldn't have been worth it for Mr. Rabbi. The rabbi was very kind to all the children. The boys would misbehave, but he didn't care, and on top of it gave out candy. He taught us Hebrew and back then I quite liked it, because it seemed like drawing to me, and the rabbi was very pleased by that. I had always liked to draw. Otherwise the rabbi didn't give us any tests, he just told us things.

Back then in Brandys there was no organized Jewish community as such, and I don't know who organized religious education, and invited Rabbi Mandl to Brandys. To tell the truth, I don't even know who organized the services in the synagogue. My brother Viktor only recalled that our neighbor, Mr. Eisenschimmel, sang beautifully in the synagogue. The Eisenschimmels had a small textile store in Brandys. They had two children, unfortunately their mother died suddenly. We only started coming into contact with most Jewish children during the war, during the time when we could no longer go anywhere, and weren't allowed to associate with anyone else but Jews. Then Jewish children would come to our place, to the courtyard and garden, and we'd play ping-pong or volleyball.

Once, still before the war, there was a big celebration in Brandys. A rare statue that some farmer had plowed up in his field was being exhibited in the Church of the Virgin Mary in Stara Boleslav. They called it the Czech Palladium. Pilgrims would come to the church, and each one of them would kiss the statue. I remember that my classmate Anca Zakova and I went to see it. When it was my turn to kiss the statue, and I saw the hordes of people that had kissed it before me, it seemed a little unpleasant to me, and so I only pretended to kiss it.

My whole generation was of the Masaryk 8 - Benes 9 school. These were concepts that we all believed in, and that gave us a feeling of national pride. My mother's sister, Aunt Elsa, occasionally spoke German with her friends, and due to this I was sometimes a little obnoxious, it seemed to me that she should rather speak Czech. When I'd come to visit, my aunt would always in the company of her friends say about me: 'She's a big Czech!' One day I saw President Benes with my own eyes. I participated in high school games that were this prelude to the All-Sokol Slets [Games]. We were marching through the Prague Castle, where Benes was standing in the court with his wife and was waving to us. We all shouted and waved. It was probably the most beautiful day of my life.

In Brandys I also experienced a visit by the Romanian King Karol 10, and Prince Michal 11. They were on their way somewhere, through Brandys, all the members of their delegation had beautiful uniforms. They were driving on the main road that led by our house. I remember that we stood on the sidewalk and waved.

As opposed to art, we never devoted ourselves to music. My parents did buy me a piano, and for some time I went to Mrs. Vrbova for lessons, but because I don't have musical hearing, I didn't do well. Plus the piano was in the old bedroom, which was heated only in the evening, because only my youngest brother with his nanny slept there, but during the day it was always cold in there, so I had to sit at the piano in a coat, once I even wore gloves. My youngest brother Jiri, as opposed to me, apparently had perfect pitch, already in the 1st grade his teacher said that he should take lessons and play some instrument. Unfortunately he couldn't take any lessons, because before the war he only managed to go to 1st grade of elementary school, and he wasn't allowed to finish 2nd grade, and what's more our father wasn't in favor of it.

Already as a little girl I liked to read very much. My parents never showered us with presents, but always for birthdays, name days or Christmas we'd get books. When I was about 14, I also used to go to the library. I remember that when I brought some new book home from the library, my father would always confiscate it and read it. But my father also bought books for me.

I had almost all of Jirasek, I also subscribed to F.L. Vek, published in individual booklet sections [Jirasek, Alois (1851 - 1930): Czech writer of prose and playwright]. I used to go to Mr. Kubac for them, and I always looked forward to each new chapter. I also had a beautiful gold and white edition of Philosophical History. But most of all, still before the war, I loved Wolker and his poems [Wolker, Jiri (1900 - 1924): Czech poet]. My mother allowed me to buy his entire work, which was composed of three books, and it wasn't only poems.

My parents supported my reading, they only didn't want me to read girls' novels. Not that they outright forbade me, but they didn't like to see it, and neither my father nor my mother would ever have bought such a book for me.

Already from the age of eight I took German, later also French and English. Between the wars I took private German and French lessons from Miss Maschnerova, who herself published in Leipzig very good and well-arranged German, French and English textbooks. Miss Maschnerova was the most expensive language teacher in Brandys, an hour cost 20 crowns, which in those days was a lot of money. I was the best in German, in Terezin I had no problem speaking with people from Germany, Austria or Holland. But I never spoke to Germans of higher standing, because they didn't talk to us at all.

The thing that I maybe liked drawing most of all was fashion. I wanted to be a fashion designer, because from the time I was little I had been interested in clothing, and I also liked to draw. I always covered all my school exercise books with all sorts of fashion designs. I'd enjoy organizing fashion shows. Sometimes I regret that I didn't at least go to family school in Brandys.

Before the war, in the summer, besides going to Doubravice, we'd always also go with our parents on vacation to Spindleruv Mlyn, that was during the years 1932-1938. My father would order a taxi in Brandys, so we'd go from Brandys to Spindleruv Mlyn by car. When we were there for the first time, I was about eight years old. My mother was expecting my youngest brother, Jiri. I remember that back then we stayed in the Belveder hotel, but later we always lived in the Hotel Esplanade. The owners of that hotel, the Blechas, already knew us, and they'd call us in advance that our rooms are already reserved, and whether we were coming. We used to go there up to when I was 13 or 14.

Because my father liked to walk, every day we'd go on big hiking trips in the surrounding countryside. We'd for example walk around the Bile [White] Labe, where there were loads of waterfalls, and also the chalet 'U Bileho Labe.' One year by the Divci Lavka [Maidens' Footbridge], which was in the valley under Spindleruv Mlyn our father built us a small wooden waterwheel, which turned as the water spun it. When we returned there the next year, we were ecstatic, because the waterwheel was still there! I remember that in the store by the bridge down in Spindleruv Mlyn they sold peaches, but because they were too expensive, my mother always bought us one apiece.

As I've already said, we used to go to Spindleruv Mlyn by taxi, because my father never wanted a car. There were always two or three taxis standing in the Brandys town square, either Skodas or Tatras, and evidently it wasn't as expensive as it is today, so we could afford it. Once our family friend, Dr. Laufer, also took us in his car, when we wanted to go to Bysice, near Vsetaty, where my father's parents are buried. But since I was little I hated cars, I got nauseous in them, I threw up, the same in buses. When we used to go to Spindleruv Mlyn, our first stop would always be at the edge of the forest before Mlada Boleslav, and then we'd have to stop a few more times along the way. It wasn't at all pleasant. Back then they used to give me these pills for nausea, they were called Vazano, but they didn't help me.

Together with Dr. Laufer my father bought two parcels of land in the forest by the road behind Stara Boleslav. They had a common fence, and in the middle stood a low shed. My father paid about 500 crowns for the shed. We spent weekends there, but we never slept there, because that little shed was kind of makeshift, and my mother wasn't the type for those sorts of things. In the morning we'd go for a walk across the fields to our parcel, and in the evening we'd walk home again. My mother would always prepare some meatballs or some other food to take along with us.

I wasn't too interested in boys. Once in high school, when I was in third year [Grade 8] some boy came up to me and wanted to borrow my German textbook. They called him Sextan, because he was in Sexta [sixth year of high school or Grade 11]. When he then returned the book to me, he'd left a letter in it. It was horrible. He was asking me out on a date, but I guess I don't have the courage for these things, it didn't at all occur to me to go on it. But my girlfriends and I decided that we'd go see if he would really come to the agreed-upon place. We stood on the bridge across the Labe River, looked down and he was already there, waiting. Afterwards I was very embarrassed. He married very early. At home we didn't talk about these things at all. To tell the truth, my parents never told me what I was or was not allowed to do in this area.

Another memory is tied to the last high school games before the war. When we were returning home from these games by train from Prague, several of us were sitting together and fooling around. A fairly nice-looking boy was sitting behind me, I think he was named Jelinek. After the high school games he would stand across from our house and look to see if I was there. Today there are 'panelak' apartment buildings there [colloquial name of blocks of high-rise panel buildings in the Czech Republic and Slovakia constructed of pre-fabricated, pre-stressed concrete], but back then there was an old linden tree across from our house, beneath it a pump and behind it a wall that surrounded a large garden. In that wall there was a little chapel. Before the war there used to be a procession from Prague to Stara Boleslav that used to walk through Brandys every Sunday. The pilgrims would always wake us up in the morning, when they would sing 'A thousand times we greet thee,' and because they had to walk a long ways, they would stop under the linden tree by the chapel, have a drink of water, wash their feet and rest.

When once after the high school games I looked out the window, that Jelinek boy was standing under the linden tree with his bike. He stood there several times more, looking into the window and looking for me. I knew that he was standing there, but it would never have occurred to me to go down and say something to him. During the war he was jailed by the Germans, when there was a wave of arrests of university students 12. In the end they let him go again, but that was already a different situation. We weren't allowed to go almost anywhere, and we had to wear a Jewish star 13, so everyone was afraid to associate with us.

In Stara Boleslav, before the war, there used to be a confectionery on the main square that belonged to the Horacek brothers, where all the students used to go. Inside there were leather booths and small café tables where it was pleasant to sit. They had excellent sweets there. But most often we used to have a so-called 'atmosphere,' which was whipped cream sprinkled with cherry brandy. I used to go there with Anca and other friends, and then also right before the war with my cousin from Doubravice, who back then lived with us along with her family after the Germans had annexed the Sudetenland 14. We'd either sit and talk or play various games, for example we'd write some word on a piece of paper, then folded the paper over so that the word couldn't be seen and when each one of us added more and more words, in the end it would result in some funny nonsense.

University students used to go to that confectionery as well. There I met Jirka Maruska, a university student, who I dated for a while. He was six years older and much more mature than I was. His father was the mayor of Stara Boleslav. Once Jirka was walking me home, and on the bridge we met my father. He was walking on the other side of the bridge, he didn't even stop and acted as if he didn't see me. As soon as we started wearing Jewish stars, Jirka didn't want to have anything to do with me any more.

Back then I used to wear this hideous green coat. Our house was next door to some apartment buildings where the tailor Rotek lived, and my father had him make a suit for him, and ordered a coat for me, so Mr. Rotek would have some business. But I didn't like the coat at all, I literally despised it. Luckily when I was about 14 or 15, my mother had my first coat made for me with her tailor, Mr. Chmelicek in Smichov, which I liked very much. Always, when I went on a date, I'd ask my mother if I could take the better coat, because it hung in my mother's closet. And my mother never said no.

I had this one friend who was named Lada Koliandr. I didn't meet him until wartime, at the post office. For a long time he used to come visit us, even during the time that it was already dangerous for him, because they could have thrown him in jail for it. He was very nice. He rounded up for us everything that we needed. He got us flannel shirts, warm socks, gloves. Once he even brought us a bow and arrow, so that we wouldn't be bored, because at that time we were almost never allowed to go out. He would usually come to our place in the evening, so that no one would see him. At that time the Vohryzeks from Doubravice were already living with us. At the beginning of January 1943 our family was leaving for Terezin, and at the same time Lada Koliandr left to do forced labor in Germany, because his year of birth was between 1921 and 1924, and all those born then were sent there.

In 1938 we went to Doubravice for summer vacation for the last time. I remember that already back then in the region around Teplice, which was in the Sudetenland, Henlein's supporters 15 were already showing their teeth. They used to walk around in white hose, leather pants and salute and yell 'Sieg Heil.' We, Czechs, in return began to wear the tricolor [the three colors of the Czech flag]. I remember that when I was about 14, some Jews were escaping from Germany to Czechoslovakia, they were going to various towns, making the rounds to Jewish families and were forced to beg or ask them for some support. When the Germans annexed the Sudetenland, the Vohryzeks and Munks had to move away from Doubravice. The Munks then lived someplace in the Zizkov quarter of Prague, and the Vohryzeks moved in with us in Brandys.

Aunt Elsa always used to tell me that I'd go to dance classes in Prague, and I'd always answer back that I didn't want to, that I was going to go to classes in Brandys. I was very much looking forward to going to dance classes, I even grew my hair out because of them, because before that I had short hair. Unfortunately I never managed to go to any dance classes before the war, because soon we had various prohibitions and limitations imposed on us, and we weren't allowed to associate with anyone.

When the war began, I was 14 and a half. On 15th March 1939 the Germans arrived. That day there was a blizzard, it was snowing horribly. I was in school, in high school, and I remember that Helena Mareckova, Pepik Marecek and Zdenek David, my friends who I used to hang out with and who were about six years older than I, came to meet me at the school and walked home with me. In the main square in Brandys there were already Germans on motorcycles with sidecars. It was a horrible feeling, to see them there. I got home, I remember that we had garlic soup and cream of wheat for lunch.

The next day we got a notice in the mail that my father has to close his office. All doctors and lawyers had to immediately cease practicing. The Czech law and medical associations were glad that they had gotten rid of Jewish doctors and lawyers. They immediately confiscated all the money we had deposited in the bank. I managed to finish my fourth year of high school [Grade 9] but then I wasn't allowed to go to school any more, so I actually didn't graduate. Unfortunately, neither did I finish any school after the war, because I was awfully afraid of math.

During the war all three of us children got scarlet fever. Back then the Germans already wanted to move us out of our house and take it over for themselves. Once they came to our house, and when they found out that we all had scarlet fever, they quickly left and then they apparently were afraid to come over, and so we were able to live in our house until our departure on the transport.

During the war my father was the head of the Jewish religious community in Brandys nad Labem, to which also belonged Jews from villages around Brandys. Because progressively various orders, prohibitions and regulations came, and someone had to take care of administration, to keep track of the Jewish population and send out this information to them. My father was forced to take this position upon himself and set up an office in our former dining room, where he officiated. Often Germans would come to our house. Once the Gestapo rang the doorbell, and my brother Viktor went to open the door. They got horribly upset at him, because he wasn't wearing a Jewish star. For we had to wear the star at home, too.

During the war I at first helped my father with administrative work related to the running of the Jewish community in Brandys, and then they sent me to work in the forest. There I worked together with other young Jewish girls, from July 1942 until December of that year. Back then we'd already had to hand in even our bicycles, but because the work in the forest was far away, on the other side of Stara Boleslav, they lent us bikes, and so every morning I rode with a hoe tied to my bicycle to go work in the forest.

In the beginning it was horrible, because we didn't know how to do anything. The forest warden for example told us to dig some holes for planting trees or sowing seeds, and then left, and we stood there, not knowing what to do, so we started to dig and dig until we had dug a huge pit, and the forest warden then came back, threw up his hands and said that it was supposed to be a shallow little trench. Most often we worked in the meadows, and because it was summer, it was usually terribly hot. My cousin always had horrible headaches from the sun. But gradually we somehow got used to it and in the end we got to like going and working in the forest.

What I liked most was working with hay. On the other hand, the worst of all was picking potatoes behind the devil. The devil was a machine for plowing up potatoes. It drove quickly, so there wasn't even time to straighten up. We gathered the potatoes into baskets, dumped them into sacks and threw them up onto trucks that then carted them away. The sacks were terribly heavy, so it was very arduous work. Back then the gathering of hay and picking potatoes fell under the Forestry Service. The forest warden was very nice to us.

Besides us there were also some women forestry workers working in the forest, who weren't there to do forced labor, and had worked there before the war. As Jews we weren't allowed to associate with them at all. The forest warden always said that he much preferred to work with us than with 'those bimbos,' that all they are is vulgar, and that with us it was fun. Once he even brought us some sweet stuffed cakes, because back then we had almost no tickets for anything, not for meat, nor butter or fruit and vegetables.

The only thing we had during the war was this artificial honey, which was really disgusting, horribly sweet, sticky, and had an unpleasant taste. I don't even know what it was made out of back then. My mother would always pack us two slices of dry bread with this artificial honey between them, which by lunch would have soaked into the bread, so it wasn't very good. But my mother still had some Van Houten puddings at home, so she'd always make some pudding and put it in a glass for me to take with me. It may have been made with only water, but back then I liked it.

We got a very small salary, on the order of crowns and halers, but always when I brought at least some small sum home, my mother was glad, and I had the feeling that I was helping to feed the family. When we were supposed to go to Terezin, the forest warden tried to save us, and asked to be allowed to keep us for forestry work, that we were terribly important there and that without us nothing was possible. Of course he didn't succeed.

People from Brandys weren't allowed to associate with us at all. They weren't allowed to say hello to us, and when we went shopping, we had to be served last of all. During the war even our neighbors from across the fence, before we were supposed to leave on the transport, came to our house by the back door and took duvets and curtains home, with the excuse that after all we can't leave them there. As I've already said, the thing that I most regret is that they also took the picture that my father had painted. Everyone then hoped that we wouldn't return, so that they wouldn't have to return anything to us. Then when my mother and my youngest brother returned to Brandys, I arrived somewhat later, those people had our curtains hanging and no one remembered the picture any more. My mother didn't want to ask anyone for anything, as she wasn't attached to any property, and in the end it didn't matter to her anyways, when my father didn't return.

Before we left for Terezin, my father would make various hiding places for money. He had several gold St. Wenceslaus ducats. My father would make for example little sewing kits with a double bottom, and would put one ducat into each one. He hid money in shoe polish, for example. Unfortunately I don't know where these items ended up.

Some time before our departure for Terezin we had to leave for Mlada Boleslav to the local castle, where they had moved all Jews from Mlada Boleslav, and there we had to hand in all of our jewels and enroll for the transport. Before we left for Terezin, I also got jaundice. I was constantly feeling awful and throwing up, and didn't know what was wrong with me, until finally my eyes turned yellow. So I left for Terezin already ill.

We left Brandys on the transport on 5th January 1943. It was a day later than the rest of the Jews from Brandys, due to the fact that my father was the head of the local Jewish community. That day we on our own left our house for the train station and took an ordinary train to Mlada Boleslav. We had sacks instead of luggage, because they didn't allow us to have suitcases. It was a strange feeling, to be leaving home with only a few bags and leave everything there. Apparently after our departure the Hitlerjugend 16 were in our house. After the war there was a music school in our house, and the principal's apartment.

On the way to Terezin we stopped in Mlada Boleslav. There they concentrated us in some school and then we continued on the transport to Bohusovice. From there we went to Terezin on foot, because at that time the tracks didn't yet lead directly into Terezin, those were built later by Terezin prisoners. From Bohusovice to Terezin we were led by our people, Czech policemen. In Terezin we were handed over to German women, who were called ladybugs. They rifled through our baggage and took what they liked.

First I lived together with my mother and many other people in the so- called Hamburg barracks. Later they emptied the Hamburg barracks and made a so-called 'slojska' out of it. It was a place where they would herd all the people who were called up for the transport, they'd shut them up in there, and directly from there they would get on trains which then aimed for Auschwitz and other places.

Between the wars my father had been in the Association of Czechs-Jews 17. Sometimes I suspect that maybe someone from that association took my father's side and thanks to this our family didn't leave on the first transports from Terezin to Auschwitz, but we all stayed in Terezin for a relatively long time. Very few people from Brandys stayed in Terezin, mostly they right away went further onwards, most often to Auschwitz. For a short while our friends - the Laufers - stayed in Terezin, but they then had to leave. Not even the fact that during the war they all had themselves baptized helped them.

The first person that I got to know in Terezin was Jirka Maisel from Caslav. He was maybe a year older than I. We used to walk around Terezin and would always be talking about something. He'd tell me about school and about student life. He even lent me some blanket so that I could cover myself better, as back then my jaundice was still on the wane. Later I met my husband there.

In Terezin, that was a diet. They used to give us this gray water to eat, which they called lentil soup. Sometimes there would be a bit of turnip or potato floating in it. About once a week they gave us a small piece of meat, but more often than not it was some piece of sinew.

Due to my jaundice I visited some doctor there. After talking a while, we found that our high school principal had been his teacher! This doctor wrote me up a disability slip, but already in March 1943 I had to go to the Terezin employment office and began working. For everyone had to work their so-called 'Hundertschaft,' or a hundred hours of work. [The German term 'Hundertschaft', usually refers to a military or police group of a hundred men, and not to working hours.] I was able to pick either work in the mechanized woodshop, or to do the cleaning in the hospital for those with typhus. I preferred to choose the woodshop. We worked in three shifts - from 6am to 2pm, from 2pm to 10pm, and from 10 pm till the morning. At night the 'Obersturmbannführer' [Lieutenant Colonel] Karl Rahm himself used to occasionally come check up on us, to see if anyone was sleeping there. I don't know what would have happened if he would have found out that someone was sleeping during the night shift. Likely he would have given that person a thrashing, or shot him, probably whatever occurred to him at that moment.

Later my husband used to tell how he arrived in Terezin on the very first transport. Back then Terezin's original inhabitants still lived there, who had to move away. It was necessary to build bunks for the emptied barracks and also beds for the normal houses, where Germans then lived. That's actually why the mechanized woodshop, where I worked from March onwards, came into being.

So I stayed in the woodshop. There were a lot of young girls like me there, which was really great. We were always singing, and we had this one excellent, merry co-worker there who entertained us. He sang us songs by Voskovec and Werich 18. In the end I found out that he was my husband's friend. There I learned how to hammer together bunks and beds. We also made latrines and these standalone little wooden shacks. In Terezin there was a warehouse of hearses, on which we carted around material ourselves. We'd load it up on a hearse, two girls pushed from behind, two stood on the sides, one at the drawbar, and like this we drove around Terezin. We'd stack it up somewhere, perhaps carry it up for installation, and then drove back.

In Terezin I also ruined my feet. When I went to Terezin, I took with me these beautiful shoes, which Mrs. Krejcova from my father's office had some shoemaker in Prague make for me. But after a year in Terezin I had worn these shoes right through. Because in Terezin everyone had the right to have their shoes resoled once a year, this is what I did, and I never saw them again. They sent me to some warehouse with men's shoes, so I could pick some different shoes as a replacement, so I picked some boys' shoes, and that's what I then walked around in, even for some time after the war. After the war I was even married in them, because I didn't have any others! Otherwise in Terezin I wore these flimsy canvas shoes, something like today's tennis shoes, but those are at least a little shaped because of flat feet. This was only this husk, a piece of canvas with some rubber. Since I was always standing on concrete in them, my feet then hurt. Due to this my arches fell and from that time onwards I've had trouble with flat feet.

Once in a while it was possible to send a parcel to Terezin. It could have been about once every three-quarters of a year that we'd get a special stamp, which had to be sent to relatives, and with this they could send a five-kilo parcel. A parcel without this stamp wouldn't get to Terezin, and we got only a very few stamps.

Once in Terezin my father gave me this tiny wooden box with a little board that slid out, which he had made himself, drew some national motif on it in pencil, or perhaps a little heart, I don't exactly remember any more.

My mother's sister, Elsa, and her husband were also in Terezin. My aunt would always promise me that after the war she herself would arrange my wedding dress. Understandably this never happened, because neither Aunt Elsa nor her husband ever returned. They left on a transport, the same as the Vohryzeks, my father's sister and her husband and daughter, to Auschwitz, where they were in the so-called family camp 19 for half a year. In March and July 1944 it was liquidated, all of its inhabitants were sent into the gas. Our relatives, the Munks, went on a transport from Prague directly to Lodz and then to Riga, where they were most likely shot.

My husband was my boss in the mechanized woodshop, and thanks to this we got to know each other. I remember that it was my birthday, and he somehow found out about it, because otherwise we didn't really talk much, and suddenly for my birthday he brought me some chocolate-covered orange peel, which I loved. I was completely in seventh heaven from that orange peel, I kept it under my pillow and didn't eat it at all, because I wanted to save it!

In Terezin my future husband was trying to convince me to marry him. He explained to me that if we weren't married, they could send me away alone on a transport, and he wouldn't be able to help me in any way. In the end I agreed. We found some rabbi in Terezin, who married us, but after the war the officials didn't recognize our wedding, so we had to get married again anyhow.

My husband, Rudolf Kovanic, was born on 16th December 1908 into a Jewish family. Before the war he graduated from business academy and worked for the Justitz company in the grain wholesale business. He spoke fluent German and for a long time also studied English. His father was a traveling salesman, so he was often on the road and apparently also liked to play cards. My husband didn't inherit this passion from him, on the contrary, he never liked cards. His mother was a nice-looking lady, she took very good care of herself. Her maiden name was Kafkova.

My husband was one of four children, he had two brothers and one sister. His sister Hana is still alive, she was the youngest of all the children. She was born in 1920, so she's four years older than I am. The youngest of the brothers was named Karel. In appearance and personality he was similar to his father. While he didn't finish council school, in the end he earned the most money of all the brothers. He had a franchise from some shoe company. He survived the war, but unfortunately neither his wife nor child returned. He had a very pretty wife, and in Terezin they even had a beautiful little girl. She was like a miracle, chubby, with rosy cheeks, she was named Alenka.

The middle brother was named Franta [Frantisek]. He was the only one of the brothers to serve in the army. Franta didn't return after the war. At first he was in Auschwitz, and then they sent him to work in Glivice 20 in Poland, where he died of blood poisoning. His wife Truda along with little Janicka [Jana] died in Auschwitz. Because in Auschwitz all mothers with children went straight into the gas.

My husband's mother was a very kind lady and managed to still get to know my father and mother. My parents liked my husband a lot, only he seemed a little old to them, as he was almost 16 years older than I. But our father was also ten years older than Mother, so it wasn't anything that unusual. My husband was an amazingly kind person. I probably have never met a kinder person. Unfortunately due to Terezin he had serious emotional problems, he almost had a nervous breakdown there. As I've already said, he was in Terezin right from the beginning, in all for about four years, which must unavoidably have marked him in some way. What's more, my husband had a relatively large amount of responsibility in Terezin, he already begun there as an administrative manager, later they entrusted him with further tasks.

People in Terezin were desperate, and for example stole wood for heating, or tried to improve their lot in other ways, but often there would be checks done, which, if they found out anything like that, would immediately have caused my husband to be arrested by the Gestapo. Once, when my husband had some problem of this type, he was completely down-and-out because of it, luckily in the end the matter was resolved only with the ghetto's Jewish leadership, which was presided over by some Mr. Freiberger. Because Terezin had this Jewish self-government, it was called the 'Ältestenrat' [Council of Elders]. Once, another thing that happened to my husband was that he met the supreme commander of the ghetto, Karl Rahm, who out of the blue told him to take off his glasses, and gave him a couple of cuffs. Basically the Germans could do with us what they wanted.

Once our entire family was summoned to a transport. The transport summonses were delivered at night. It was a horrible feeling, at night someone would bang on the door and bring a thin strip on which was written who should present themselves where and when. We had to gather in the 'slojska,' which as I've already mentioned was a building that was open at the back, from which one would leave directly into the courtyard to the transport, because at that time the track right to Terezin had already been finished. So Rudolf volunteered, that he's going with me.

They told us that there'd be a selection in the courtyard. It was the first and last selection in Terezin, otherwise the selections weren't done until in Auschwitz. Apparently the selection was aimed only at young people, because neither my father nor my mother was summoned to it. Rudolf went with me. We all walked by the Terezin camp leader, Karl Rahm. Whoever Rahm didn't stop, automatically went straight onto the transport. Us he stopped. He asked me where I worked, and I told him that in the woodshop. Rahm was familiar with the woodshop, plus I had overalls on, as I didn't have anything else. Rahm then asked Rudolf, and he told him that he was with me voluntarily, because we were going to be married. Back then in Terezin it was possible to apply for a civil wedding, which we had done. Rahm bellowed 'Ihr werdet heiraten!', which meant we didn't have to get on the transport, that he'd rejected us.

In October 1944 we were supposed to go onto the transport for a second time, and again we were rejected. I think that Rahm rejected all those that worked in the mechanized woodshop. The first time Rahm rejected my husband's sister like he had us, but the second time he didn't reject her. The last brother, Franta, worked in the constabulary service, you could recognize it by this special cap that he wore. Apparently he had gained some esteem, so he went to see Rahm and told him that in Terezin they were three brothers, a sister and mother, and if he could leave the sister, Hanka. Rahm agreed.

My husband's brothers, Franta and Karel, were often mentioned in connection with Terezin culture. One of them, Franta I think, wrote the so-called 'Terezin Hymn' to the melody of Jezek's 'Song of Civilization.'

In Terezin I had to lug around horribly heavy things, so once it even happened that my back went out and then I had to lie in bed for three days without moving. After the war it happened again, I've got a herniated disc, lower back problems.

My older brother, Viktor worked with the carpenters in Terezin. Back then he was about 14. Like all manual laborers in Terezin, he also got a tiny food supplement. In the morning and evening we got black 'Melta' [a coffee substitute] in our canteens and besides this one piece of bread for the whole day. We always tried to divide up the meager ration, one little slice for breakfast, one little slice for supper. Viktor could never hold himself back and always ate all the bread at once, so then he had nothing left.

Our father went to Auschwitz on the very last transport, my brother went on the transport before him. My mother remained in Terezin, because she was working for the German war industry, she peeled mica for German airplanes. My mother had these short, fat fingers and I guess she wasn't very good at it, because she always had problems filling the required quota. Finally they fired her, but it was too late for her to leave on a transport. My youngest brother Jiri was in Terezin with our mother the whole time, back then he was about 13 years old.

For sure our father went directly into the gas. Because back then he was 58 years old, and apparently they sent everyone from 55 up into the gas. My husband had two brothers and two sisters-in-law with beautiful little children in Terezin, but both mothers with the children went to Auschwitz and there directly into the gas.

When my brother Viktor went to Auschwitz, he perhaps wasn't even 14 yet. Some SS soldier on the ramp apparently asked him how old he was, took his watch and advised him to say that he's a year older, and only thanks to this was my brother saved and didn't go directly into the gas. From Auschwitz he got into Kaufering, which was a branch of Dachau. [Editor's note: by the Dachau concentration camp, the Nazis set up two huge underground factories - Kaufering and Mühldorf, where they then transferred the chief portion of arms manufacture; mainly Jews from Poland, Hungary and the Baltics worked here in inhuman conditions.]

There he got typhus. Apparently they left him lying there with the others in some pits, and then they loaded them onto open wagons and were taking them to the gas chambers. In the meantime the Allies bombed the train, so it remained standing somewhere on the track. My brother's friend from Prague died there by the morning and my brother was found by the Americans, who dressed him and sent him to a hospital, where spent a long time. Apparently they found him as a human skeleton, he weighed 28 kilograms.

For a long time we had no news at all of him, not until sometime in August 1945 when he wrote Mrs. Krejcova, our family friend and household helper. Because my brother thought that none of us had returned. Mrs. Krejcova immediately let us know that my brother was at a sanatorium on Sokolska Street. His nerves were completely shot and he was also in horrible physical shape. For a long time after the war, he didn't want to talk about anything that he had lived through.

It wasn't until sometime after the war that I found out about the International Red Cross's visit to Terezin. As I worked three shifts, I had practically no means of finding out what was actually happening in Terezin. I only know that at that time they had built a music pavilion and set up a park in the town square.

Towards the end of the war, it was sometime during the winter, they sent me to do agricultural work. It was during the time when many people had been sent away from Terezin on transports, so every bit of help was welcomed. Surrounding Terezin there were these moats, where I cut willow branches for the basket-weaving workshop. A Czech constable used to go with us. Some lady that was working with us apparently had a husband or children in Prague, and used to give letters to the constable for him to send. This kind of thing, however, was very risky.

Sometime in January 1945 my husband and I left Terezin on a transport to Switzerland. No one actually properly knew where we were really going. After the war I read somewhere that our transport was supposed to have been in exchange for prisoners of war. It's true that when we arrived in Kostnice, the train station was full of bandaged people, without arms, without legs. Apparently Hitler had forbidden this transport, but because it was already almost the end of the war, one of the highly placed people around Hitler took it upon himself.

First they took us to the town of St. Gallen, where we were quarantined in some local school. Then we passed through three camps in various places. The first was in Adliswil, which was a village not far from Zurich. There were two halls there, which had once belonged to some small factory, which however was no longer functioning. In one of the halls they put up men, in the other women. It wasn't an actual work camp, we worked there only for our own needs. For example the men used to go into the forest to collect wood, and the women peeled potatoes. There were also children in our camp, and the soldiers that were taking care of the camp even brought us exercise books and pencils, so we then taught these children to write and count.

Apparently the Swiss weren't very glad we were there. They even wanted to send us to somewhere in Tunis or Algeria, but we didn't want to go. You see, we knew that the end of the war was approaching. Finally they transferred us to Les Avants in the mountains, where for some reason there were completely empty hotels, without any furniture or accessories, so we had to sleep on mattresses on the ground. I remember that we rode up to Les Avants on a cogwheel railway, and as we came out of the tunnel, a beautiful view out over Lake Geneva opened up in front of us, I'll never forget that.