Gherda Kagan

Odessa

Ukraine

Interviewer: Natalia Rezanova

Date of interview: January, 2004

Gherda Isaacovna Kagan lives in a standard house in Filatov Street. She has a slightly neglected three-bedroom apartment where she lives alone. The apartment is modestly furnished. Books are most valuable in the apartment. There is a big collection of art albums, in particular. Gherda looks young for her age. She is very friendly. She was ready to do her very best answer all questions. She has a very correct literary manner of speaking. She had considered writing her family history and Gherda Isaacovna was very happy that we showed interest in life stories of her relatives many of who had really interesting personalities.

My maternal great great grandfather Mordko Voolih was born in 1783 in Valachia [historical region in the south of Romania], where the surname of Voolih derived from. He moved to Odessa in the first years of the 19th century and took part in construction activities. He managed to start his business. He owned an alabaster plant. He had three wives and many children, of whom I have no information. In the late 19th century the family of Mordko Voolih lived in their own three-storied house in 13, Srednyaya Street. My grandmother Esphir told me that at his age of 103 everybody got tired of my great great grandfather Voolih and she, his 6-year-old granddaughter, was the only person to mourned over his death in 1886 .

One of Mordko Voolih’s sons, my great grandfather Meir Voolih, inherited his alabaster plant. Like all Voolih men he was a fair-haired giant with an open cheerful character. Sitting at the table he liked joking that he was eating alabaster kugel [pudding from matzah or vegetables]. Meir was happily married and had four sons. His wife Yenta was very religious and the family followed kashrut and observed all Jewish traditions for the love and respect of her. Yenta wore a wig and wore her kerchief above her ears. At Yom Kippur, before going to the synagogue, my great grandmother cleaned the house, locked the food and gave her husband a bunch of keys. My great grandfather secretly gave children the keys and they could eat anything they wanted while their great grandparents were away. Yenta also had a sense of humor. When gefilte fish was on the table and her four sons were screaming: one wanted gefilte carp, another wanted pike and the third one wanted some other fish, she cut a piece from the same dish and served it to her sons saying: ‘here is your carp, and your pike, etc. They were a good Jewish family. Meir’s older son insulted the family honor. He was eager to study and to overcome the problem of the limited quota he got baptized and went to Petersburg. In the end he became professor of mathematic of Petersburg University. My grandmother Esphir, his niece, told me that when she studied in the university and saw the surname of Voolih on a textbook she asked at home whether it was their relative. In response she heard of storm of curses addressed to ‘this black sheep and turncoat’. Later, when few nephews wanted to get higher education and went to Petersburg to make it up with their uncle, professor kicked them downstairs. My great grandfather Voolih was paralyzed 13 years of his life and died in the early 1910s. Great grandmother Yenta died in 1912. They had four sons: Itzhak, Shaya, Berk, Huna and two daughters: Luba and Esphir.

Esphir, the younger daughter, became my grandmother. She was born in Odessa in 1877. She finished private grammar school. My grandmother was shortsighted and said that she ruined her eyesight reading at night with a candle under a blanket. My grandmother was a pretty blond when she studied in grammar school. She said that when she was a senior student her teacher of drawing was not indifferent to her. Grandmother Esphir wore elegant clothes when she was young. My mother told me that she had beautiful outfits decorated with bugles. She kept her fancy gowns in a bog box and during a general clean up before Pesach she took them out to air them. There was a housemaid and a cook in the house. Esphir was so scared after a pogrom in Odessa in 1905 1 that my grandfather sent her and their three small children – Yulia, David and 6-month-old Raisa (my mother) to Vevey town in Switzerland for a year. They stayed in a boarding house. My grandmother Esphir wasn’t religious and didn’t observe any Jewish traditions. After the funeral of our religious great grandmother Yenta my 6-year-old mother asked during dinner: ‘Is this a meat or dairy knife?’ and my grandmother Esphir answered that there were no meat or dairy knife, there were only steel or silver knives. This was the end of religiosity in our family. After October revolution 2 my grandmother was very unhappy about having to cook her first soup at the age of 45 after they lost a cook and wash the staircase in the corridor like all other tenants. Of course, she didn’t approve of these ‘’niceties’ of Soviet life and having to stand in line to buy food products. During horrible famine in 1921 3 grandmother Esphir took her family to Druzhelubovka Voznesensk district of Nikolaev region, to a former estate of Odessa artist Nikolay Kuznetsov where she visited when she was young. In 1920 a sovkhoz was organized in this estate. They stayed there with their relatives’ families for a year, working in the garden, keeping livestock, making brynza and mamaliga and managed to survive.

My maternal great grandfather Abram Zivik owned a shop in Privoz [a big market in Odessa], where he sold grain and seeds. My great grandfather had four children: Maria, Anetta, Lev and Boris. I knew my great aunts. Maria Galperina had no education and wasn’t a nice person. She was selling something in Privoz and lived in the Zivik family estate in Privoznaya Street. She died in the early 1960s. Anetta was her opposite: she was an educated and nice lady. She married Lev Gerzhberg, a doctor. My grandfather’s younger brother Lev finished Polytechnic College in Liege before the revolution and worked as an engineer in the Yanvarskogo Vosstaniya plant. He perished at the plant in 1941 during the Great Patriotic War 4 from a direct hit of a bomb.

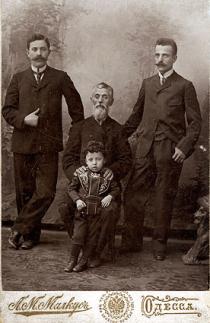

My maternal grandfather Boris Zivik was born in Odessa in 1877. His real name must have been Bencion since his son David’s patronymic was Bencionovich according to his document and besides, my father called him Benito in a teasing manner. Grandfather Boris went to cheder. He inherited his father’s store. He expanded his business and was selling wheat for export. He studied Italian, French and German. He needed foreign languages to interface with his foreign partners. When he became a merchant of guild II 5, my grandfather provided financial support to revolutionaries. After the October revolution, when authorities came to expropriate his property, my grandfather gave away everything he had on his own good will. There were never any regrets in the family in this regard. After the revolution my grandfather worked as lid operator in a small factory of diet tinned food located in the yard of our house. Later he became a cashier in Odessa hydro airport in Odessa harbor. He was very much interested in political events. When he came home from work, grandfather Boris took off his uniform coat and cap and the first thing he did was turning on a big plate of the radio on the wall in the hallway to listen to news. During the great Patriotic War grandfather Boris miraculously managed to get out of Odessa in siege. Brother Lev gave him his departure permit. My grandfather reached his daughter Yulia in Tbilisi and then in October 1941 he died of stenocardia attack when he heard that Germans captured Odessa. My grandfather’s mother tongue was Yiddish. He talked Yiddish with grandmother Esphir sometimes. There were three children, born in Odessa, in the family.

My mother’s sister Yulia was born in 1889. She finished private grammar school and was to be awarded a golden medal for her successes. She actually didn’t get it for having one ‘4’ for her behavior. Yulia was an unbelievable chatterbox. In 1917 she entered the Medical Faculty of Novorossiysk Emperor University and after graduation she worked as a lung roentgenologist. She married Grigoriy Oswald who had finished the Art College in Odessa and they moved to Moscow. In 1928 their son Victor was born in Moscow. Grigoriy Oswald was a horder by nature. They came to Moscow without any belongings, but soon they had an apartment and a dacha. Aunt Yulia easily spent money and didn’t value what they had. They divorced due to this difference of attitudes in 1938. During the war Yulia and her son were in evacuation in Tbilisi. Her husband Grigoriy Oswald perished at the war. His 14-year-old son Victor and his friend decided to go to the front. Militia captured them at a railway station when they were eager to return after they saw so many wounded going by trains. After the war they returned to Odessa. Victor finished Odessa Polytechnic College and got a job assignment 6 in Komsomolsk-on-Amur. Later he moved to Kishinev where he worked as an engineer at a plant. Yulia lived with her son in her last years and died in 1970. Victor died in 1993.

My mother’s brother David was born in 1902. David was a naughty boy. They could see a fire tower from windows in their apartment. This 4-year boy liked firemen passing by in their copper hard hats. He set white fringes of a tablecloth to have them come to his home. David was a gifted boy at the same time and his family teasingly called him ‘Boris professor’ at home. David went to study in realschule 7 where he continued to be naughty. Once director invited my grandmother to visit him. She heard her son calling him ‘shkalik’ [a small bottle of vodka] at home and when she came to school she addressed him ‘Mister Shkalik’. During the Civil War 8, when David was 18 he fell under a romantic impulse and joined Kotovskiy 9 cavalry. When he faced the reality of rough military life he returned home a month later. David finished Electric Engineering Faculty of the Polytechnic College. He married his neighbor Basia Kleiner who had finished 8 years of grammar school and worked as an accountant her whole life. Uncle David lived with his wife’s family. In 1935 their daughter Yelena was born. The girl had bright red hair and there was a lot of confusion in the family until they recalled that their long liver great grandfather had a red beard. David worked as an electrician at the Bolshevik plant. In 1941 he and his family evacuated with the plant to Kinel station near Kuibyshev. After the war they returned to Odessa and David continued to work at this plant as a shop superintendent. Uncle David was fond of stamps and was one of the oldest members of the society of stamp collectors in Odessa. He died in 1970 and was buried in the Jewish cemetery. His wife Basia died three years later. Their daughter Yelena finished Technological Faculty of the Refrigeration College and worked in Odessa by her specialty. Now she is a pensioner.

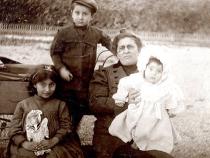

My mother Raisa Zivik-Kagan was born in 1906. When my mother was six the family lived in a big house on the corner of Yekaterininskaya and Malaya Arnautskaya Streets in the center of Odessa. They had an apartment on the third floor and on the first floor there was a dog that my mother was scared of. Once, when my parents went out David climbed under a bed in the dark room and barked. This caused consternation that developed into a heart disease that my mother suffered from for the rest of her life. She stayed in bed for a year and had to give up music. Doctors didn’t allow her to study at all. It was hard for the girl to go up to the third floor and my parents found another apartment in a house in Starosennaya Street. My mother was a very sensitive girl and probably, that was why she drew well. Being bed-ridden for along time she made many drawings. She climbed a windowsill and from there she threw all her drawings to local children. In 1916 my mother’s older sister Yulia took my mother to a private grammar school and said to a grad looking porter: ‘if she is late, don’t let her in’. And my mother had this memory, as she said ‘like a stone on her heart’, for the rest of her life. In 1920, when the grammar school closed, my mother went to the Odessa school of applied arts. There were wonderful teachers in this school. My mother made friends with two girls and they kept in touch until the end of their lives. The name of one of them was Gherda and my mother named me after her. My mother finished this school in 1925.

With her friends she entered Odessa Art College. My mother was eager to join Komsomol 10, but since she was a ‘lishenka’ 11 they didn’t admit her, but since she could write well they made her responsible for Komsomol meeting minutes. The only thing she didn’t like was ‘simpleton’ Komsomol behavior like walking embracing one another, for example. When they were five-year students, my mother and her friends were expelled from college for being ‘alien elements’. They went to Kharkov, the former capital of Ukraine and managed to have them restore their status as students in college. Students of the Art College washed their brushes in kerosene that they bought in a store across the street from their college. There was chemical school across the street and students took their primus stoves that they used to experiments to the store to fill them with kerosene. In this store my mother met my future father Isaac Kagan. When my father accompanied my mother home for the first time he asked her when they reached the tower in Richelieuvskaya Street: ‘What? It’s even farther? I can’t walk any more’. My mother got angry, being a proud girl, and this might become the end of everything, but they met again in the store and made it up.

My paternal grandfather Samuel Kagan was born in Mogilyov town in 1860. In Odessa he was a clerk in a store. My father said that grandfather was a member of Odessa society of support of clerks. On Friday, when grandfather’s working week came to an end he looked into his son’s sins in a past week. His children waited for this moment with trepidation and tried to delay it as far as they could. They knew that as punished they might not be allowed to have their favorite delicacy: khalva. Their trick was in asking mother for another cup of tea and them she added some more khalva in their saucers. From what my father told me I know that grandfather Samuel, like many Jews who had come up in life from its very bottom didn’t admire the tsarist regime and supported revolutionaries with money. Grandfather Samuel died of cholera during an epidemic in Odessa in 1920. He was buried in the Jewish cemetery.

My paternal grandmother Revekka Kagan, nee Spivak was born to an intelligent Jewish family in Nikolaev town in 1870. Her sister Adel Spivak lived in Nikolaev and it’s all I know about her. Her brother Veniamin Spivak was a well-know therapist in Nikolaev. His son Grigoriy became a mathematician, professor of Moscow University. Another brother Akim Spivak emigrated to Sweden in the early 20th century. He lived in Stockholm. In 1912 Revekka, her husband and children visited her brother. My father corresponded with Akim before the war, but then it became rather unsafe and their correspondence terminated. My grandmother Revekka was a housewife. They spoke Yiddish at home. Revekka wasn’t strongly religious, but she went to the synagogue with her husband and children on holidays. My mother told me that Revekka was a very interesting person. She was a smart lady. Even her female cat was particularly smart. She followed her mistress to the Privoz, waited for her at the gate and then came back home with her. Grandmother Revekka died in 1932, shortly after I was born and I didn’t see her. I liked her face looking at her photos and her curly hair cut short. My grandmother and grandfather had two sons: Isaac, Grigoriy and daughter Clara.

My father’s older brother Grigoriy Kagan was born in Odessa in 1897. Before the revolution he finished Odessa Commercial School. After grandfather died in 1920, he went to work in Nikolaev where he married Isabella Lisogor. He worked as an accountant in ‘Soyuzpechat’. I remember that before the war, when it was a problem to subscribe to children’s magazines, my uncle Grigoriy arranged it for me in Nikolaev and then relayed them to Odessa. Grigoriy’s daughter Tusia was born in the late 1930s ad in 1940 his son Samuel was born. Grigoriy was at the front at the age of over forty. He was a soldier and perished in late 1944 near Mogilyov in Byelorussia. During the war his wife and children evacuated to Frunze [Kirghizia]. My parents sent her money and parcels whenever they could. After the war it became known that besides parcels from my parents Isabella also received parcels for starved families. My parents thought it extremely indecent of her to behave so and terminated their relationships with her.

My father’s sister Clara Kagan was born in Odessa in 1901. She finished Odessa Medical College and married her cousin brother Semyon Manteifel. They moved to Petersburg where her husband’s relatives owned a photo shop in a garret on the fifth floor in the very center of the town. Since Clara and her husband were very proud of this our family called the ‘Barons Manteifels’ jokingly. They had a daughter named Galina. During the war Clara and her daughter evacuated somewhere to the Northern Ural with a children’s boarding school where she worked as a doctor. Her husband perished at the front. After the war Clara returned to Leningrad. She died in 1952. Her daughter galena finished Agricultural College in Leningrad. She married a man whom our family didn’t like whatsoever and we didn’t stay in touch with them.

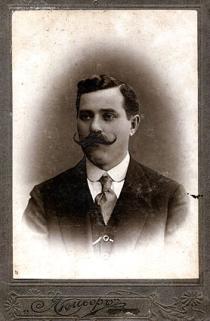

My father Isaac Kagan was born in Odessa in 1904. He was raised with strict rules in his childhood. In 1920, when my father became an orphan, the family where he lived didn’t have money to buy him clothes. They made him rag shoes with rope soles. He used to play football wearing them and his sister Clara had to fix them every night expressing her distress about his conduct. My father finished a Russian grammar school and went to work at the glass factory: he needed some work experience to be able to continue his studies. My father told me that he intentionally didn’t wash after his work shift and went home in Bolshaya Arnautskaya Street across the town by tram so that everybody could see what a real worker he was! When he gained some work experience my father entered Odessa Chemical School. When he was a student, this school was given a status of college. My father finished it in 1928 and became a specialist in food preservation. He went to work at the tinned food factory at the Karpovo station near Odessa. He told me that his career started with an accident. At the height of the season the factory stopped operations and it turned out that a frog got into the pipe pumping water to the factory from the Karpovka River.

My parents got married on 11 November 1929, a year before my mother finished her college, on my father’s birthday. During my parents’ lifetime this day was a major family holiday. After they got married my father went to work at a big factory of tinned food in Tiraspol in 1929. My mother stayed in Odessa, but she often visited my father in Tiraspol. The town was so dirty that she lost her galoshes in the mud and never found them. My mother finished her college in 1930. At that time my father was arrested in Tiraspol. He was arrested for being a favorite student of his professor related to ‘Prompartia’ (‘the Industrial Party’) [The trial in the end of 1930 wherein the group of engineers were accused of creating anti-Soviet illegal organization.]. The professor was executed and my father managed to survive. He was transferred to a jail in Odessa. They began investigation and half a year later my father was released. Through this period he never had a chance to notify his mother or wife where he was. In the 1980s, shortly before he died, I began to ask my father what happened to him then, but my father said: ‘No, I signed a non-disclosure agreement’. In the middle 1980s, at the incentive of perestroika, 12, I thought of visiting Odessa KGB office 13, to read my father’s file and find out the truth, but I never overcame my fear of KGB that was in my blood to go there. After my father was arrested my mother went to her sister Yulia in Moscow. My mother worked in ‘Selkhozgiz’ publishing office in Moscow illustrating agricultural books. She had a hard life in Moscow. There was a coupon system. When my father was released he came to Mother in Moscow. In Moscow he managed to find a job in the people’s committee of Food Industry. My father worked there few months. Since he hated routine paperwork he requested a transfer to another job. They sent him to Leningrad where the newly weds settled down in my father sister Clara’s apartment.

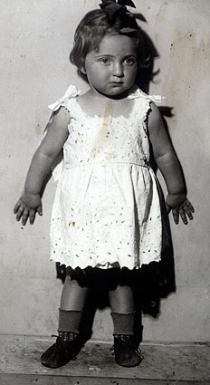

I was born in Leningrad in 1932. My grandmother Esphir came to Leningrad to take us back home. Being three weeks old I was taken to Odessa in a basket for chemical containers with a lid. When axle boxes in the train caught fire I was handed from one carriage to another in the basket that had turned upside down, as it turned out. After we arrived in Odessa my father went to work at the local affiliate of the All-Union scientific research institute of refrigeration industry. My mother was a housewife and activist in the women’s council of the house of scientists. My parents moved into my grandfather Boris and grandmother Esphir’s three-bedroom apartment in Starosennaya Street. While my mother was away grandmother gave her permission to his nephew and his wife to move into the best façade room with a balcony. They were supposed to move out when we arrived, but it didn’t happen this way. They had guests at night enjoying drinking parties. The nephew’s wife had tuberculosis and intentionally spit around the corridor. My parents took me to the toilet holding my hand to prevent me from touching anything. This couple was spoiling our life until 1941, when we left Odessa.

I attended classes of a Frebel teacher 14. Her name was Wilhelmina and she was German. We, kids, called her Tante Minna. My parents sent me there hoping that I would study German, but all we learned was ‘Oh, tanenbaum’. She taught us embroidery and modeling. Wilhelmina lived at the dacha in Srednefontanskaya Street. Every now and then some men visited her. She called them nephews. We, children, couldn’t stand them. After the war I got to know that Wilhelmina’s place was an office of German intelligence and her ‘nephews’ were agents. It was a smart disguise: children, dancing classes and holidays. I was 5 years old when Spanish children [Editor’s note: the USSR supported republican units in Spain during the Civil War in 1936–1939. After they were defeated, many Spanish children were taken to the Soviet Union] arrived in Odessa. They were taken along Richelieu Street from the harbor to the railway station and we stood on the corner gazing at them.

There was a children’s club in the house of scientists and I often went there. There was a huge picture of Stalin holding a little girl on the wall. We knew that her name was Ghelia Markizova and she handed Stalin a bouquet of flowers at the congress. I envied Ghelia terribly. I have a small bust of young Lenin at home. There was a whole iconostasis on red goffered paper over my desk: Lenin 15, Stalin, Kaganovich 16, Voroshilov 17, Kalinin 18. When I was 6 I had an audition in the house of scientists and when they asked me to sing something I didn’t sing them about a hedgehog or New Year tree, but I sang a heroic Soviet song ‘Partisan sailor Zhelezniak’ and the commission was amused.

There was a staircase behind one wall of or apartment and my father told me that they couldn’t sleep for months hearing boots tapping on the stairs at night and they didn’t know who was to be arrested that night. During the period of arrests [Great Terror] 19 my parents never discussed this subject in my presence since I was an open-minded girl and a chatterbox. I remember that Ira Ghefter, granddaughter of my grandmother’s sister Luba, visited us before the war. She was a little older than me and I asked her usual questions about where her mother or father was and she avoided answering me as much as she could. When I grew up I got to know that her parents fell victims of arrests. Milliant, director of the institute where my father was working, who contrived polish for lids was arrested in 1937. His wife, a former class tutor of my aunt Yulia in her grammar school, and her sister didn’t have anything to live on and I remember that my family tried to support them.

At five I learned to read well, but my writing was poor. They didn’t want to admit me to school at the age of 7, but when I turned 8, I took an exam and admitted me to the second grade. I felt very hurt. First grade schoolchildren were greeted with an orchestra and flowers and when I came to school nobody paid any attention to me. There were only two marks at school: ‘good’ and ‘excellent’. My first mark was ‘good’ in behavior. I came home very proud, but my mother told me off so seriously that I understood that I was not allowed to chat in class. Before the war I didn’t understand the difference between Jews and Russian. I believed that since I was born in Leningrad in the USSR I automatically became Russian. My parents never told me that I was a Jew. I saw all children with painted eggs at Easter while I never had one. When I asked my mother she said: ‘All right, next time you will have one’ and I calmed down.

In 1939 my father went to work in ‘conservetrest’. All food preserve factories all over Ukraine were under its supervision. He also did diploma designs at the institute to earn more for the family. My father was very strict, serious, pedantic and demanding and was a very hardworking person. He read many technical books and wrote articles. Before the war he was awarded the title of candidate of sciences 20. The subject of his dissertation was introduction of glass containers in food preserve industry. This subject was significant for economy and Mikoyan [then narkom (minister) of food industry of the USSR] awarded my father a trip to Sochi in 1938. My parents went for this vacation in a recreation center together. Our life improved. We bought new furniture: a wardrobe, a double coach and a desk. We also had an old carved cupboard of my grandmother’s. There were carvings of game, fruit and a fowling bag. My father dressed modestly, but my mother gave much thought to her clothing. Before the war she had a faille de Chine purple dress made by Ivia, a popular dressmaker in Odessa. She also ordered matching shoes. My mother tried to get nice clothing for me. I remember having a fancy velvet dark green suit. My mother met a less expensive dressmaker when she was young and she made clothes for me.

In spring 1941, probably under the influence of conversations that I heard I had a dream that Germans came and grabbed me by my plaits and pushed me down to the flame on a primus stove. I woke up from horror. On 22 June, on Sunday, I was having a music class in our neighbor’s room since there was no space for a piano in our room. As a rule, my mother sat there with me, but this time she sent me to practice alone. An hour later the hostess said to me: ‘Your mother is looking out of the window. She wants you to come home’. They told me at home that a war began. From the first days a public garden near the railway station was full of refugees from Bessarabia 21. Tenants of our house went to dig shelters under the supervision of our house maintenance manager. We, children, delivered water in cans.

On 12 July uncle David, the first one in our family, left Odessa with the Bolshevik plant. People were saying: ‘Why leaving? Germans are decent people’. I witnessed my grandmother arguing with Jewish glasscutter Kogan. He was yelling furiously: ‘Germans are decent people!’ They were almost on the edge of fighting.

My parents and I and grandmother Esphir evacuated with Conservetrest at dawn on 22 July, actually one hour before the heaviest bombardment of Odessa. There were small boats called ‘dubki’ hauling watermelons from Kherson to Odessa. We went to Kherson on one of them. Then we went by boat up the Dnieper to Zaporozhiye. My father went to town to listen to news and he bumped into two of his colleagues from Odessa. They yelled at him: ‘Are you out of your mind? Go pick your family and join us in the train’. This was one of the last trains leaving Zaporozhiye shortly before the town was given away. This train often stopped on its way. We arrived in Northern Caucasus. When the train stopped we bought everything people brought to sell: hard-boiled eggs, bread and boiled potatoes.

In Apolonskaya village of Rostov region all passengers were sorted out and we went to Asinskaya village in Chechen Ingushetia where there was a tinned food factory. It was August, vegetable harvest time, and my father spent days and nights at his factory. He was the only man in the shop. My mother, grandmother and I fell ill with malaria. The three of us were in a small room where only three beds fit. Our hostess, an old Kazak woman, came into the room. She stood at the foot of my grandmother’s bed asking one question: ‘Still alive?’ Later, when we felt better, we started talking to her and she asked: ‘How about Jews – are they Russian?’ It was a surprise for her to know that they weren’t. Shortly afterward my father got a transfer to a tinned food factory in Bazorkino village in 20 km from Ordzhonikidze where he became chief engineer. There was a sovkhoz growing vegetables for this factory and there was a steppe around. We also had a vegetable garden and I took to liking gardening then. к My mother worked at the tinned food factory. She checked the quality and identified the cost of vegetable shipments. I didn’t go to school. My mother was afraid of letting me out of the house. There were rumors that Chechens kidnapped Russian children. My mother taught me the curriculum of the third grade at home. In summer 1942, when Germans were advancing to the Caucasus we evacuated along the Military Georgian Highway 22 to Tbilisi on trucks. There we stopped at my mother sister Yulia’s home. From Tbilisi we moved on by the train shipping equipment of the tinned food factory. My father was appointed chief of the train. When we were boarding the train we were robbed. Somebody stole our documents and warm clothes. Nobody cared about the factory equipment in summer 1942, and our train was traveling across Transcaucasia until late fall. We ate the remaining tinned food. Children gathered dry grass when the train stopped and then adults made fire on two bricks in railcars. They boiled a bucket of water and added a tin of meat, a tin of green peas, a tin of rice and 2-3 potatoes that we bought from locals and it made lunch of all passengers of a freight carriage. My father always joked that not a single employee of tinned food industry has starved to death.

In autumn we crossed the Caspian Sea in 8-grade intensity storm and moved on by train. My mother fell ill with jaundice. When we arrived at Kagan station in Bukhara region [Uzbekistan] I went out alone looking for a toilet. While I was away my father obtained food and traveling documents and the train departed. The train used to wait at stations for weeks before, but this time our railcar was attached to a military train and it left. Half-blind grandmother Esphir didn’t notice that I was not there, but my mother felt that there was something wrong and cried out to father: ‘Gherda is not here!’ He jumped off. He had a fur vest and a satin jacket on top of it on and this was late November. My mother crawled to the door to give him some money. My father kept the amount of 30 thousand Soviet rubles being chief of the train. He kept this amount in my schoolbag. My mother saw that my father couldn’t possibly find the bag on tracks and decided against dropping it. Having no money and starved we managed to catch out train few days later in Tashkent. My father met his colleagues from Odessa again and they convinced him to go to a tinned food factory in Andizhan.

In Andizhan [3 500 from Odessa in Uzbekistan] I finally went to school. My classmates were mainly children of evacuated families. One of them was Glukhov, an overgrown boy four years older than me, a very annoying albino boy with white hair and red eyes. He beat me so hard for my being a Jew that I decided for myself, being only 11 years old: I should marry a Russian man so that my children didn’t suffer as much as I did. Schoolchildren went perform concerts in hospitals and also gathered clothes for them. I saw many severely wounded maimed people and since then there is nothing more fearful than a war for me. My father was chief engineer. We lived on the territory of the factory and he stayed there day and night. Once he decided to go to the cinema with us for the first time in two years and it was then that a boiler exploded at the factory. Once my father received a thick flannelette cut at the factory. It was nicely patterned. My mother had a nice dress with woolen trimming made for her. This was her only dress since all clothes had been stolen from us.

In 1944 my parents decided to return to Odessa. This wasn’t an easy thing to do: they needed a pass, permit and documents. My father went to Moscow to obtain permission and we lived with uncle David’s family at Kinel station near Kuibyshev through that winter. There was no job in Odessa and my father was appointed to restore a tinned food factory in Tiraspol. We lived there for a year. Victory Day in Tiraspol is one of the strongest impressions in my life. When at half past five in the morning we woke up from crazy knocking on the door, my father decided that the factory exploded. It turned out they woke him up on the occasion of the victory. There was a small square in front of a garden in the central square. Everybody came there including schoolchildren and we, pioneers, were there wearing our red neckties. It was warm and sunny and there were lilac trees and tulips in blossom. It was so beautiful. Everybody smiled, but when they said ‘Glory to deceased heroes’, every single person burst into tears!

There was a nice collection of books in the library of the house of officers in Tiraspol. I read a lot. We had wonderful teachers at school. Our teacher of mathematic Sophia Yakovlevna, she was an old lady, struck us by addressing us with the polite form of ‘You’. She told us that she studied in a school for girls in Petersburg before the revolution. I remember her respectful manners. Our Russian teacher also had different teaching methods. For example, she suggested that we wrote an ending of Pushkin’s novel ‘Dubrovskiy’ by ourselves when we were in the 6th grade. Our teacher of biology was at the front in Germany and brought from there a suitcase full of microscopes and we could use them. Schools were struck with poverty. For example, I went to school with a stool that my father made for me. There was a Gestapo office in the school building during the war. The building was cleaned off and whitewashed afterward, of course, but on one staircase all doors were locked and there were planks across them. We stuck our noses through one door and saw bloodstains and hair tufts on the walls.

In 1946 we returned to Odessa. I heard that my teacher of music and her mother were buried alive. She was so beautiful and so kind and I’ve never got over this. There were other tenants in our apartment. When we were still in Tiraspol, my father applied to court to have our apartment back, the court refused him. My mother and father made the rounds of their acquaintances looking for our belongings. Romanians took away all better things. We found a mirror, grandmother’s box, carved walnut wood sticks with bronze incrustation, damaged by shipworms. Our neighbors told us that the janitor had our wardrobe. When my mother went to see the janitor’s daughter, her friends, they grew up together, she showed her an ax from behind the closed door and said: ‘If you make a step, this ax will damage the wardrobe first and then you will know it as well’. We lived in the territory of the plant for a year and a half and I went to school #103 in Moldavanka. We studied French. My grandmother helped me to improve my French and I finished the 7th grade with an award for my accomplishments. In 1947, at the age of 14, I joined Komsomol.

In 1948 all of a sudden we received a parcel from my father’s uncle Akim from Stockholm. He, knowing that we were having a hard time, sent us two cuts for coats through the Red Cross via Palestine: one cut for me and another one for my cousin from Leningrad. I was 15 years old and had a raglan coat made for me in the latest fashion. My friends didn’t have anything to wear and they were starved and I felt ashamed of wearing this gorgeous coat. In due time I had it turned and made a longer jacket from it and later we made a coat for my little daughter from it. This was the quality of this English fabric.

In 1948 we received an apartment in Bolshaya Arnautskaya Street, 19. I went back to my first school. It was a school for girls now. I studied there for three years. There were wonderful teachers who gave me knowledge and raining to serve me for the rest of my life. There were 13 graduates with medals in our graduation classes in 1950. At the prom they first handed school certificates and then those who had gold and silver medals were invited to the stage where they greeted us, but we didn’t have our certificates yet since medals were to be approved by higher authorities. A week passed and it was high time to submit my documents to a college, but I didn’t have my certificate. There was another victim: Natasha Kibertseva, a Jewish girl from another graduation class. My father went to find out what was wrong and they told him to forget about my medal. My father was acquainted with ‘fair’ Soviet law proceedings and was not going to fight for the medal with authorities. Fortunately, Kibertseva and I managed to enter colleges without medals, though this was the first year when Jews began to face obstacles entering higher educational institutions. There was struggle against cosmopolitans 23 in process. Many of my Jewish friends failed to enter colleges, though they studied as well as I did. I entered the technological department of tinned food of the Food Industry College. When I became a student this dressmaker that my mother knew made me a suit from inexpensive half-woolen fabric of bottle green color.

The period of ‘doctors’ plot’ 24 went past me somehow. I was in love and was engaged with my private life. However, I remember very well the Stalin died. We heard the news at home and I went to college by tram #23. Usually old Belgian trams, jogging and rattling were never quiet or boring. There was always a wit with his jokes or some wicked woman starting a wrangle in a streetcar. On that day it seemed there was nobody in the tram. It took me a while to get to Grecheskaya Square from Bolshaya Arnautskaya Street and there was deathly silence all this trip. In college a young teacher came into the classroom. She had tearful eyes. She sat down and looked at us. Somebody sniffed and then everybody had tears poring down: we cried after Stalin for an hour and a half. I went to study English at school at that time and I was walking home late at night. There wee deserted streets and mourning music sounded from windows.

In 1954, when I was a 4-year student I married Yevgeniy Grinblat, a 5-year student of Flour grinding College. He was born in Odessa in 1931. His maternal grandfather Boris Vladimirskiy was a townsman from Tiraspol. He was selling fruit in Odessa. My husband said that there were always tangerines and oranges on his birthday in December and on new Year. His grandfather wasn’t religious. Although he wore a yarmulkah, he always said it was to keep his baldhead warm. He went to the synagogue in Pushkinskaya Street on holidays with the only purpose to meet with his old friends. He didn’t go inside, but stood in the crowd in front of the entrance talking. My husband’s father Moisey Grinblat was an accountant and worked in a shop manufacturing ship models before the war. There are many of their works kept in Odessa Navy museum. During the war his family evacuated to Ufa and then to Baku with this shop. After the war they returned to Odessa, but they couldn’t have their former apartment back, either. They received a worse apartment in Uspenskaya Street. Moisey Grinblat died a sudden death in 1948. My husband’s mother Rosalia Grinblat worked as an accounting assistant in various offices. Hey were cultured people. My husband’s uncle, his mother’s brother, was a big theatrical administrator in Odessa. Actors who came to the town on tours visited them in their house in Preobrazhenskaya Street.

After finishing his college my husband received a job assignment to work on a new elevator in Novosibirsk, but he fell ill and recovered three months later when there was no more vacancy there. He went to Moscow to obtain another assignment. They offered him work in Uryupinsk town in Volgograd region. My husband was chief mechanic at a plant. I defended my diploma and went to work at this same plant as a forewoman. There was something wrong with our life there right at the beginning. Director invited us to his office and said that a shop superintendent who had a small child had a very small room and asked whether we could let him move into the apartment that was supposed to be given to chief mechanic of the plant. How could we say ‘no’? We found ourselves living in a very small room with little windows and my husband could touch the ceiling with his palm, though he is not a giant. There was no running water, thought there was a factory boiler right against our windows. Nobody cared about installing 20 meters of piping to supply water to three plant houses. We had to go up the hill three blocks away to the to a town pump: an example of Soviet attitude to people.

In late 1955 my husband fell severely ill with spontaneous pneumothorax. At that moment I happened to break my leg. My mother was severely ill and already obtained required documents for a surgery, but she gave it up and came to Uryupinsk to attend to my husband and me. My husband’s friend Anatoliy Timokhov who was at the front during the war and now worked at the district Party committee as an instructor showed us a report of Khrushchev 25 on the 20th Party Congress 26 in 1956. My mother, my husband and I read it commenting and remembering different events. I always knew that my father, a decent honorable man and excellent specialist, was innocent, but sent to prison, but we couldn’t know the whole truth. Stalin was commonly believed to be a nice person and many people wrote him letters seeking for help. After this report, we thought, everything was going to well. We had a new country and new government.

In 1956 we returned to Odessa and settled down in my husband mother’s apartment. My husband went to work at the design office of machine building plant. I found a vacancy of rate setter technician at the rate setting research laboratory at the food industry headquarters. I worked there three years, but I didn’t like this job. Nobody needed it. My father was working at the scientific research institute of food industry. He was a scientific deputy director. I went to work in the laboratory there. I was an active Komsomol member and in 1957 before Moscow Festival of young people and students my husband and I went to the harbor to meet Arabs and Negroes going via Odessa. We wanted to see a foreigner. It was like a miracle for us. They turned out to be human beings like us, nothing special.

In 1958 our daughter Natalia was born. My parents received a new apartment. They exchanged it for two rooms in communal apartments in Pushkinskaya Street so that my husband and I could receive an apartment for us. I could hardly cope with everything and was stupid to give my 6-month-old baby to a nursery school. Natalia became very sickly. My parents helped us again. They bought a dacha at the 10th Fontan station [resort area in the town] so that their granddaughter could improve her health condition in summer. Grandmother Esphir who managed to nurse her granddaughter died in Odessa in 1962. She was buried in the Jewish cemetery.

In 1962 I joined the party, but not for the sake of ideas. I had my personal reasons. Firstly, all of my former co-students were members of the party already and I was used to belong to the advanced circles of masses. Secondly, I was concerned that if my father quit his job at the institute I might lose my position of scientific employee and interesting work. My father never joined the Party, although they were trying to convince him. He teased me about it. My mother took my side. She believed joining the Party was a formal procedure necessary for a career. My mother had a surgery: they removed a cancer tumor. She died in 1971 and was buried in the Jewish cemetery.

My daughter Natalia went to school in 1963. She had expressed Jewish looks and she suffered a lot from anti-Semitic demonstrations of her classmates at school. As a result, she developed a strongly negative attitude toward her Jewish identity. At the age of 11-12 my daughter got fond of drawing and attended classes in an isostudio in the Palace of pioneers. Hen theater became her hobby. She attended a theatrical studio and was going to enter the theatrical College after finishing school in 1973. My husband and I thought that she needed to study a profession first. Natalia reluctantly entered the school of Soviet trade. After finishing it she worked in ‘the house of toys’. Her management valued her high, but Natalia was attracted to the theater. She went to work as an usher at the Ukrainian Theater and then became an electrician to have an opportunity to travel with the theater. She met Sergey Skripunov, Russian, at the theater. He came to Odessa from Vorkuta. He studied at the Mechanic Faculty of Theatrical School and worked as a scenery assemblyman in the Ukrainian Theater. They got married in 1980. Many employees of the theater came from Western Ukraine and had strong anti-Semitic moods. They said to Sergey: «Why did you marry a zhydovka [abusive word for a Jewess]?’ They moved into a four-bedroom apartment. It belonged to the theater and there were three other families living in it. There was one stove for four families in their 5-square-meter big kitchen. One actor’s wife pushed down all casseroles from the stove to put her own on when she came into the kitchen. So, my daughter spent weekends with me.

We had a good life in the 1960s - 1970s. My husband was chief engineer of a plant and earned well. I also had a high salary. I often went on business trips all over the country. I met people in planes, at railway stations and in hotels. I was sociable and liked talking with people. I was a devoted Soviet person for a long time. Although I saw mismanagement and bureaucracy in our tinned food industry, I thought they were our local drawbacks related to Odessa area. I read Soviet newspapers and believed that everything was well in the soviet country. My daughter always laughed at me calling me an idealist. My husband was critical about the soviet reality. He went crazy seeing Brezhnev on TV. I asked my husband to not criticize the soviet regime in a loud voice for the fear that our neighbors could hear him.

My husband continuously faced discrimination: they never gave him permission to travel abroad due to his national identity. He was sure that KGB had information about his aunt who moved to America before the revolution and sent her relatives in Odessa minor money amounts via a bank. When new director with anti-Semitic convictions came to the plant, my husband began to have problems. I’ve never been ashamed of my nationality, but sometimes I had to keep silent about it. Since I have Slavic appearance, they often told me anti-Semitic stories in lines or elsewhere. I listened quietly and then mentioned that I was also a Jew and watched their reaction. I’ve always identified myself as a Jew, but we never thought about any Jewish traditions in our house, particularly religious, and never celebrated Jewish holidays. My mother or father never showed any interest in them until the end of her life.

I was an active member of the party and was fond of public life. I was responsible for the wall newspaper and I also participated in a team of agitators during elections. Of course, I knew how useless and insignificant my efforts were. When voters didn’t appear at elections my senior comrades pushed their bulletins into boxes before my eyes. When I was a member of district commissions, they sent me home before the day was over. I had no objections and one could only guess how they wrote those minutes or signed them. No decent person likes to take part in forgery, but I understood that if I wanted to leave the Party, it was like the end of one’s life: everything would be threatened – one’s work and attitudes of surrounding people. So I kept quiet.

My father died in 1981. He was buried beside mother in the Jewish cemetery.

In 1982 my daughter’s son Alexandr was born and in 1985 - her second son Konstantin. At that time only I kept her from divorcing her husband. I thought that if life conditions improved their life would get better. My husband and I literally skinned ourselves alive. We sold everything of value we had to save for the first installment for a three-bedroom cooperative apartment. In 1987 they received this apartment and we helped them to buy furniture hoping that they would make it up. As it turned out, it wasn’t about an apartment. My daughter’s husband couldn’t care less about his family drinking and going loose. They divorced. He demanded that my husband and I should pay him a lot of money if we wanted him to leave the apartment. We did and our daughter and grandchildren could have this apartment. My husband insisted that our older grandson Alexandr went to study in the ‘Or Sameyach’ school 27, but he was expelled for bad behavior from there. He didn’t find it interesting to study in a Jewish school.

Perestroika started for me with a feeling of more freedom. In 1987 I traveled abroad for the first time in my life. I went to Czechoslovakia and Germany with a tourist group. I couldn’t travel abroad before. In Czechoslovakia young people expressed their obstruction to our group of Soviet tourists. It was more than unpleasant. Gorbachev 28 was nice compared to Brezhnev. He seemed like a sun to us at the beginning. We were happy that he was accessible. It was my understanding that the meaning of perestroika was to make things good and right. It was nicely said, but it was done as before, that’s it. People are the same and same are their attitudes, particularly in Ukraine.

In 1991 the break up of the USSR 29 was a terrible shock for me. We lost our motherland. Then I understood a phrase from ‘Hamlet’: ‘the link of times has broken’. Until today the former Soviet Union is nothing but my country for me. When my TV doesn’t function properly and I cannot watch Moscow programs, I miss them. What’ happening in Ukraine seems to me a miserable parody on what is going on in Moscow. Let them make mistakes or do things wrong, but if you have brains and if they’ve already stepped on rakes in Moscow, learn your lessons in Ukraine and do something different. Cannot Ukraine with its 50 million population find decent and reasonable people? I live here as if it were a strange country.

In 1991 my husband and I and my daughter with her sons submitted our documents to the OVIR office for departure to Israel since all of our friends had already left. We obtained departure permits when a war in the Persian Gulf began and we stayed. I feel for Israel with all my heart. I would love to live there, but I am afraid of the war. We had an opportunity to move to Australia or America, but we stayed. We shall live in our motherland as long as there is no war or pogroms. In the early 1990s my husband and I divorced. He found another woman and went to live with her. I wanted to get an official divorce, but my husband talked me out of it. He believes it might create unnecessary problems. We keep nice and friendly relationships with him.

In 2002 our daughter Natalia died. She had a weak heart that failed her during a gynecological surgery. My husband and I take care of our grandchildren. Their father doesn’t care about them. He has another wife. Alexandr is a 4-year student of Ecological University (Hydrometeorological in the past). His specialty is ecology. Konstantin is a last-year student of a machine tool plant. They come to see me, call me and help me.

I am very happy about the rebirth of Jewish life in Odessa. I enjoy going to a wonderful Jewish library in Pionerskaya Street. I receive free Jewish newspapers ‘Or Sameyach’ and ‘Shomrei Shabos’ and I collect interesting articles from there. Few years ago I established contacts with Gemilut Hesed. An acquaintance of mine mentioned to me about this organization. I registered there and then for another year I tried to convince my husband to register there as well so that we could receive two packages instead of one. Of course, Gemilut Hesed social assistance helps me a lot. They do my laundry for me. Once my shoes needed to be fixed and Gemilut Hesed paid for shoemaker’s services. Following my husband I got fond of the history of Odessa. We have a good collection of books on this subject. Few years ago they invited me to work in the town archives. In parallel I started looking for the documents related to the history of my family. I’ve found some and now I write memoirs hoping that my grandchildren would find it interesting.

1 Odessa pogrom in 1905

This was the severest pogrom in the history of the city; more than 300 Jews were killed and thousands of families were injured. Among the victims were over 50 members of the Jewish self-defense movement. Flats, shops and small enterprises were looted by the pogromists. The police stood by and did not defend the Jewish population.2 Russian Revolution of 1917

Revolution in which the tsarist regime was overthrown in the Russian Empire and, under Lenin, was replaced by the Bolshevik rule. The two phases of the Revolution were: February Revolution, which came about due to food and fuel shortages during WWI, and during which the tsar abdicated and a provisional government took over. The second phase took place in the form of a coup led by Lenin in October/November (October Revolution) and saw the seizure of power by the Bolsheviks.3 Famine in Ukraine

In 1920 a deliberate famine was introduced in the Ukraine causing the death of millions of people. It was arranged in order to suppress those protesting peasants who did not want to join the collective farms. There was another dreadful deliberate famine in 1930-1934 in the Ukraine. The authorities took away the last food products from the peasants. People were dying in the streets, whole villages became deserted. The authorities arranged this specifically to suppress the rebellious peasants who did not want to accept Soviet power and join collective farms.4 Great Patriotic War

On 22nd June 1941 at 5 o’clock in the morning Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union without declaring war. This was the beginning of the so-called Great Patriotic War. The German blitzkrieg, known as Operation Barbarossa, nearly succeeded in breaking the Soviet Union in the months that followed. Caught unprepared, the Soviet forces lost whole armies and vast quantities of equipment to the German onslaught in the first weeks of the war. By November 1941 the German army had seized the Ukrainian Republic, besieged Leningrad, the Soviet Union's second largest city, and threatened Moscow itself. The war ended for the Soviet Union on 9th May 1945.5 Guild I

In tsarist Russia merchants belonged to Guild I, II or III. Merchants of Guild I were allowed to trade with foreign merchants, while the others were allowed to trade only within Russia.6 Mandatory job assignment in the USSR

Graduates of higher educational institutions had to complete a mandatory 2-year job assignment issued by the institution from which they graduated. After finishing this assignment young people were allowed to get employment at their discretion in any town or organization.7 Realschule

Secondary school for boys in Russia before the Revolution of 1917. Students studied mathematics, physics, natural history, foreign languages and drawing. After finishing this school they could enter higher industrial and agricultural educational institutions.8 Civil War (1918-1920)

The Civil War between the Reds (the Bolsheviks) and the Whites (the anti-Bolsheviks), which broke out in early 1918, ravaged Russia until 1920. The Whites represented all shades of anti-communist groups – Russian army units from World War I, led by anti-Bolshevik officers, by anti-Bolshevik volunteers and some Mensheviks and Social Revolutionaries. Several of their leaders favored setting up a military dictatorship, but few were outspoken tsarists. Atrocities were committed throughout the Civil War by both sides. The Civil War ended with Bolshevik military victory, thanks to the lack of cooperation among the various White commanders and to the reorganization of the Red forces after Trotsky became commissar for war. It was won, however, only at the price of immense sacrifice; by 1920 Russia was ruined and devastated. In 1920 industrial production was reduced to 14% and agriculture to 50% as compared to 1913.9 Kotovsky, Grigory Ivanovich (1881-1925)

Russian hero of the Civil War. He worked as an assistant to a manor manager. He was arrested several times over the years and was even sentenced to death, but this was later changed to penal servitude for life. In 1917 he joined the leftist Socialist Revolutionaries. He carried out a heroic campaign from the river Dnestr to Zhitomir in 1918 and took part in the defense of Petrograd in 1919.10 Komsomol

Communist youth political organization created in 1918. The task of the Komsomol was to spread of the ideas of communism and involve the worker and peasant youth in building the Soviet Union. The Komsomol also aimed at giving a communist upbringing by involving the worker youth in the political struggle, supplemented by theoretical education. The Komsomol was more popular than the Communist Party because with its aim of education people could accept uninitiated young proletarians, whereas party members had to have at least a minimal political qualification.11 After the revolution of 1917 people that had at least minor private property (owned small stores or shops) or small businesses were deprived of their property and were commonly called ‘deprivees’ [derived from Russian ‘deprive’]

Between 1917 middle of 1930s this part of population was deprived of civil rights and their children were not allowed to study in higher educational institutions. Communists declared themselves to protect the interests of the oppressed working class and peasants and only representatives of these classes enjoyed all civil rights.12 Perestroika (Russian for restructuring)

Soviet economic and social policy of the late 1980s, associated with the name of Soviet politician Mikhail Gorbachev. The term designated the attempts to transform the stagnant, inefficient command economy of the Soviet Union into a decentralized, market-oriented economy. Industrial managers and local government and party officials were granted greater autonomy, and open elections were introduced in an attempt to democratize the Communist Party organization. By 1991, perestroika was declining and was soon eclipsed by the dissolution of the USSR.13 KGB, Committee for State Security

The basic organizational structure of the KGB was created in 1954, when the reorganization of the police apparatus was carried out. It was a highly centralized institution, with controls implemented by the Politburo through the KGB headquarters in Moscow. The KGB was a union-republic state committee, controlling corresponding state committees of the same name in the fourteen non-Russian republics. (All-union ministries and state committees, by contrast, did not have corresponding branches in the republics but executed their functions directly through Moscow). The KGB also had a broad network of special departments in all major government institutions, enterprises, and factories. They generally consisted of one or more KGB representatives, whose purpose was to ensure the observance of security regulations and to monitor political sentiments among employees. The special departments recruited informers to help them in their tasks. A separate and very extensive network of special departments existed within the armed forces and defense-related institutions.

14 Froebel Institute: F. W. A. Froebel (1783-1852), German educational theorist, developed the idea of raising children in kindergartens. In Russia the Froebel training institutions functioned from 1872-1917 The three-year training was intended for tutors of children in families and kindergartens.