Deniz Nahmias

Thessaloniki

Greece

Interviewer: Valia Kravva

Date of interview: October 2006

Immediately after you meet Deniz Nahmias you have the impression that you have met an important woman, a true lady, who has been through a lot and carries so many life experiences. And this is quite true: she originates from a rich and well-known family and she has met many important people. Yet, all the times we met and talked, she was really friendly and hospitable. She is now 83 years old and lives in a spacious apartment together with her beloved husband Albertos. Her son Iossif lives in another apartment in the same building. Their bond is very strong. I recall her hesitations about taking her photographs out of the house. Iossif reassured his mother that nothing was going to happen to them. Deniz Nahmias "visits" through her memories the old Salonica. Photographs and music - she is an excellent piano player - take her back to a happy and harmonious childhood. To those years that she can never forget and she recalled for me in every detail.

Starting from my mother: my mother's family owned a flourmill; it was a very rich family. My grandfather, my mother's father whose name was Isaac - Matathias Beza had a flourmill and he was a rich, well respected man back in the late 1800s. He owned a flourmill that used to grind wheat. He was very wealthy. He was born in Thessaloniki [in 1867] and also died there, in 1936 at the age of 69. In this city at that time two families owned the flourmills: the Beza family and the Allatini family 1. My maternal grandfather had five brothers but we never met them.

At some point the flourmill he owned was burned down. Maybe it was his competitors who set it on fire. This happened when my grandfather was still young. It had nothing to do with the fire of 1917 2; it happened much earlier. The competitors gave to my grandfather compensation on the condition that he'd never rebuild the flourmill, because they had always the fear that the brothers might unite and rebuild it some day. So the competitors agreed to give them a certain amount of money for the next five years. And the flourmill stopped working.

You know how it is, when there are many brothers they cannot agree upon anything, one wants one thing, the other another. From that time onwards everyone found his own way. The family of my grandfather, as I mentioned before, was very well off, so he was sent abroad to study and this is how he learned many languages: English, French, German, and thought of becoming a representative. In Greece at that time there were no factories but all the imports were done via firm representatives. Back then this was an extremely profitable and popular profession. So he became a representative of the DMC house and of other firms as well. This is how he managed to make his fortune: he established a house of imports and later his son entered the job.

He married a daughter of the Navaro family, which was also a very rich family. They owned all the area of Caravan Serai. Navaro himself was a coppersmith. At that time everything was made of copper, so he became very rich with his work. So my grandfather Isaac married Navaro's eldest daughter, Doudou, and they had two children: my mother Loucie, or Loukia, and her brother [Alfredos]. Doudou spoke French.

At that time, just before the birth of my mother, the Dreyfus Affair 3 was taking place in Europe. My grandfather was ordering newspapers from France and wanted to keep up with the case. When his wife gave birth to my mother he named her after Dreyfus's wife, and not after his mother, so he called her Loucie and later he named his son Alfred after Alfred Dreyfus. He was so moved by this case and he followed it with such great interest that he gave his two children the names of Alfred and his wife, rather than name them after his parents. This was quite unusual at that time. My grandfather died when I was twelve years old, but we were not living together in the same house. Instead he came to visit us every Saturday.

He was extremely extrovert, a very cheerful person indeed. A nice person with a lively personality. I remember whenever he paid his visit at our home he used to bring me a small doll as a present. When I turned twelve I had a party at home; I remember I had organized a party because I had finished elementary school and this was a big event those days. So, he came to my party and we were dancing 'lansiedhes.' This was a popular dance those days, not exactly a modern dance. We were dancing in pairs one after the other. And he said, 'Take two steps ahead.' This was a European dance.

When I was about twelve years old the Greek music was quite popular: 'Ririka,' 'The vest you are wearing,' but also the European tangos. Before the war, 'lansiedhes' was really popular at parties. At that time we also still had gramophones. So my grandfather was showing us how to dance at my party and he was telling us to move back and forth. He was a very lively person.

My grandfather was a pro-Mason, he was quite an educated man; that is why he was not religious at all. He was a follower of the basics of religion, for example he would eat with us during Protohronia [first day in the year in Greece] or Pascha [Passover]. And he was doing this just for his children so that they remember their home. He spoke many languages, as I mentioned before: English, French, German. And of course he spoke Ladino 4, Turkish and Greek.

His wife, my mother's mother Doudou, was already ill before they got married. She had been infected by an unknown fever so her heart had turned very weak. But no one explained to her that it was dangerous to give birth in her condition. Instead they forced her to get married; she became pregnant twice and she died six months after she had given birth to her second child. At that time she was very young, about 26 years old. My mother Loucie was born in 1895 and her brother Alfred in 1898.

My grandmother Doudou had twelve siblings. My great-grandmother - I keep her photograph - gave birth to twelve children and all of them lived. Because she was very rich, instead of breast-feeding them herself she paid a woman to do that. She was just delivering them. They were a wealthy family, enjoying good conditions of living and they passed on healthy genes. I have to tell you that it was quite uncommon at that time to deliver twelve children and to bring up all of them.

My great-grandfather Navaro was married twice, and my grandmother Doudou was a daughter from his second wife: he had four children from his first wife and twelve from his second, altogether sixteen children. And he gave them good dowries, something like 2,000 pounds to each girl.

After the death of his wife Doudou, my grandfather had to find another wife. His second wife was named Fortune and her family name was Koen. She was from Thessaloniki, her family was a good one but had lost all money, so she had no dowry and her parents were looking for a rich groom. She had not been married before; she was a virgin. After their marriage they were all living under the same roof: her parents and the newly-wed couple. She needed her mother to help her bring up the children that my grandfather had from his first marriage. So he married this woman who was not educated, a second class wife, but he had to do it because only a woman could bring up his children. Fortune Koen spoke only Spanish, Ladino.

My grandfather lived in the center of Thessaloniki, his house was on Mitropoleos Street, near Aristotle Square. He had his own house. He was living there with his first wife when I was born. But he was living in another place with his second wife; I don't remember where exactly. He had three more children with his second wife: two daughters and one son. They loved each other very much, one supported the other. I mean all his children from both marriages, and Fortune loved not only her own children but also those from her husband's first marriage. They kept on having good relationships until the end. So did we. Like a family.

My grandfather died in his office and my uncle found him. He was only 69 when he died. Quite young. He was really fine until then. He probably died of a heart attack.

My father's father was named David Angel and his wife was called Diamante, and they gave me her name, but in a more modern version, Deniz. At that time it was a common practice among Jews to give modern names. Now Christians have this privilege and we let them. I sometimes hear very unusual and funny names!

When I was born in 1924 my paternal grandfather was already dead; he must have died in about 1916. I never had the chance to meet him. My parents kept a big photograph of him but it was lost and I don't have this photo anymore. All our pictures were lost during the occupation.

Grandmother Diamante was living with us, so I do remember her quite well. People were saying that her husband was a nice man. They were brought up in the same neighborhood and their mothers were friends. At that time most marriages were arranged. So they had an arranged marriage. At that time most marriages were taking place at the age of eighteen, quite young couples. My paternal grandfather was neither rich nor poor; he came from a middle-class family, not like the family of my mother which was a well respected and well known family.

My grandfather was a merchant; he was selling leather products and products for shoemakers. He imported those products and he managed to travel to England to bring them to Greece without knowing how to speak English. He didn't speak French either, just Ladino. But he made his deals. He was good in business. My grandmother Diamante used to tell me all that, how he traveled to England and ordered the leathers to be sent here, to Thessaloniki.

My grandmother Diamante was wearing traditional clothes while Grandmother Doudou used to dress exactly the way women did in Europe; she was also wearing big hats with feathers. Diamante was still wearing the traditional Jewish costume with the 'kofya' [special headgear consisting of several caps and scarves covering the woman's hair] when I first met her, but after some time she took it off. She had two or three dresses; they used to give them together with the dowry those days. She didn't manage to get educated because a nasty cousin of hers was making her life difficult at school. Her parents were afraid that she might harm her and, because Diamante was their only daughter, they decided to take her out of school. This is why she was left without education. After that they took her to learn sewing. Grandmother Diamante died in 1937.

We were communicating with Grandmother Diamante in Ladino, we spoke French with our mother and in school we spoke Greek with our schoolmates. I remember we used to tease our grandmother by saying, 'Hey granny, you have to learn Greek.' My grandmother knew no other language apart from Ladino, but my mother learned French and as time went by she also learned Greek because our neighborhood was a mixed one. I spent most of my childhood at 25th Kritis and Marasli Streets, I mean the time before the war.

My grandmother was not religious par excellence; well, somehow she kept religious traditions and she used to go to the synagogue. But she loved to play cards, a card game called rummy. She had some friends in the neighborhood and they gathered and played cards. Once a week they used to come to our house and the rest of the time they went to other homes. Those who played cards were Jewish because my grandmother didn't have any Christian friends, as she couldn't communicate with them; she couldn't understand their language.

In front of our house, a family named Kazes, who were very rich, used to invite my grandmother to play cards. I remember that both husband and wife played. Every day, from about four until eight, I remember my granny left the house. She waited until my father had left for his work and then she went to the Kazes family to play cards. She used to go in any weather conditions: in winter with snow, in the cold, in nice, warm weather; she waited until my father had left and then she rushed to that house. Otherwise he would have seen her and of course he would have asked where she was going.

She never said a bad word to my brothers or me. My grandmother Diamante and I were sleeping in the same room until she died. Sometimes we asked her to show us how to play cards but she avoided doing so because she didn't want us to end up playing cards passionately like her. Nowadays I play 'biriba' with my friends, and so did my grandmother; she also played other games to pass the time. Even though she was an uneducated woman she was extremely clever, she even helped her children with mathematics when they went to school.

Grandmother Diamante gave birth to nine children but the first three died of diphtheria, so only six managed to survive, and all of them were girls, except my father Isaac. He was born in 1888 in Thessaloniki and died in 1945 in Athens. My grandmother treated my father with special affection because he was the only boy and, later, he kept her with him in his house. It was a common thing those days for married sons to stay in the same house with their mother.

The three first sisters of my father married while my grandfather was still alive. Then my father accepted the responsibility of marrying off his other sisters and giving them a dowry.

My grandmother told me that they were selling shoe gadgets, leathers, laces etc. in their shop. They were selling great quantities to other merchants but also small quantities to individual customers. Some of these items were produced by the girls of the family, i.e. the daughters of my grandfather instead of having the work done at the market. This is how they managed to save money and, little by little, their dowries. It was like a family enterprise.

As time went by my father became rich because the shop was doing well. He was a partner with his first cousin; initially their fathers, who were brothers, were partners and then their sons became partners as well. The shop had the following sign on it: 'Beniko and Isaac Angel.'

One can still find this shop on Edessis Four Street, near Emporiou Square. This shop and the whole building belong to us and we still owe it. Now it is shut down. A few years ago Dimitriadis, who used to sell haberdashery, paid us rent but after him we never managed to rent it to someone else. Now it is considered a preservable building and it is situated in a preservable area of the city. So it must be preserved as it is. Of course we owe this shop together with the inheritants of my dad's cousin.

Regarding my father's sisters, my aunts: The oldest was called Sounhoula, she married one Mr. Arditi; his grandson is Isaac Arditi. The second sister was called Flore, she was married to David Alfandari and she had a daughter, while Sounhoula had two sons and a daughter. Another sister was called Bienvenida. She got married to someone called Haim and both her husband and she died without having any children. The fourth sister was Dezi, this is how they called her, and she had four children: her first two children, two boys, died from diphtheria and then she had two more that still live, these are my cousins. They live here in Thessaloniki and their names are Rasel and Saoul Saporta, respectively. Then there was the youngest sister called Zouli, who married a doctor called Albertos Menasse; he is the one who wrote a book about the period he was imprisoned by the Germans in a concentration camp.

My husband's sister, Zouli Kastro, immigrated to Brazil but she was visiting us here in Thessaloniki every year. She got married in Thessaloniki and left for Latin America after World War II. Now her children live there, Erna and Zozi, who are twins. Erna went to Israel at some point and she became very religious.

One might wonder: Why did they choose Brazil? It seems that the situation was far better there because immediately after they settled there with their children their status was improved. As soon as they got there they found a groom for one of their daughters. He was a Jewish guy from Volos. Her daughter keeps visiting Greece every year with her husband because she feels homesickness, nostalgia. His surname is Sarfati. He fell in love as soon as he met her. Many Jews were living in Brazil and they were very well off and their community was very organized. The community was not devastated there. They live in Sao Paulo. They left because they were afraid of the whole communist climate in Greece after the war. That's why they left. And this was a very wise decision because they managed to find better conditions of living.

My mother Loucie was born in 1895 in Thessaloniki and died in 1995, when she was 100 years old, in Athens. Her mother tongue was French because she had attended a French school but she could also understand Ladino. No one knew Hebrew at that time; they only read the Bible [Old Testament] in Hebrew but they couldn't understand anything. Our languages were Ladino and French. So my mother attended the French school and this school was located in the market area of the city.

My mother was a fashion victim. She used to wear hats, and every year she went to the dressmaker to have new dresses made but she also altered the old ones; in French this was called 'transforme.' My mom always kept up with fashion and when she was a young woman used to wear little hats with veils. She used to wear costumes. She was really a modern woman. Special shops were selling hats, so every year my mother was buying one or two and she altered the old ones. There was a shop selling hats on 25th March Street, which was near our house. At that time some dressmakers were really expensive but you could also find cheap ones who were paid for a day's work.

Doudou Sounhami was one of the most famous dressmakers at that time; her niece is Ririka Leon. She made haute couture. Paximada was also a very famous dressmaker. Although she was a Christian many Jewish women used to go to her. Those two were the most expensive in that profession, and there were also others who were less expensive. And then some dressmakers were visiting women at home.

I remember we used to practice 'circomon' since nothing was found ready- made in the market. Especially when we grew up. Koen's shop was a famous shoe shop, and it was situated on Venizelos Street. There were some stores that were selling shoes, but they had to measure your feet. This is how they worked. And they made shoes especially for you. From after the war I remember 'Karakala' and 'Loux.' But before the war the only shoe-selling store in Thessaloniki was 'Koen.'

My mother's brothers were saved during World War II because they were Spanish citizens. My uncle, i.e. my mother's brother, Alfredos Beza, escaped to the mountains with the partisans; this is how he managed to survive the war. His sisters, who had a different mother because as I have explained Grandfather was married twice, were also Spanish citizens, and they left for Athens. But the Germans assembled all Spanish Jews in Athens and took them to Germany. When the war was over they allowed them to return to their countries.

The reason they surrendered in Athens was the fact that the Germans, since they were allies with Spain, didn't kill any Spanish citizens. So they surrendered without great hesitations and the Germans caught them and put them on a train and sent them to Germany. But after the liberation they allowed them to return. My grandfather's second wife, along with her brother, who were also Spanish citizens, were taken by the Germans from Thessaloniki to Germany, then to Spain and then to Casablanca [today Morocco] and finally to Israel. Some Spanish Jews came back and some remained there.

My mother's sisters Sarina and Irma were married to two brothers, Haim and Albertos Boton, and after the war they settled in Mexico. They were afraid because there was a popular scenario after the war that the Russians would take over Thessaloniki in collaboration with the communists. And this is why they left. I never went to Mexico to visit them but my daughter went there to find them.

Here in Thessaloniki, they owned the textiles shop 'Cosmos' on Venizelou Street. Now it has been replaced by the store 'Fokas.' The new store kept the old name 'Cosmos' for a certain period of time and then changed it.

Our relatives in Mexico came to visit us almost every year, because they were missing their old friends, especially those who had stayed in Athens. Until they were very old and helpless they used to come to Greece every year. This was very helpful from a psychological point of view because they knew that back here good and loyal friends were expecting them. They had friends that loved them very much.

My mother's sister was in Athens during the war. She was also a Spanish citizen. As I have explained, the Germans didn't kill them but they sent them to Germany. They were imprisoned in Bergen-Belsen 5 but still they had a much better life. My uncle's sister was taken to Casablanca and then to the Middle East. She got on the same ship with her husband and her daughters but her boys were forced to board another ship. The ship on which the boys had boarded sank. Maybe the Germans did it on purpose to kill them. Anyway this ship never reached its destination. It is still a mystery what happened to those people. Some argue that the ship was sunk so that the Germans could get the money of the people onboard.

My elder brother is called David, we called him Mimis, and he was born in Thessaloniki on 31st June 1918. I was born in 21st June 1924 and Solomon, my younger brother, was born on 18th October 1926, also in Thessaloniki. My oldest brother, Mimis, died at the age of 69 in Athens, while my youngest brother still lives in Athens.

Solomon was also called Haim because my mother had dreamed before delivering him of one of her cousins whose name was Haim. They also named him Reimon, because this was a really modern name when I was young. Solomon in his house in Athens keeps the double bed we used to have in the house we were brought up; this is pre-war furniture. I don't quite remember how he managed to get it back since everything else was lost: furniture, utensils, and all house equipment. But I think that our neighbor Morozinis managed to save the double bed because we had moved all our furniture to his place. And of course all the photos we kept at home were lost.

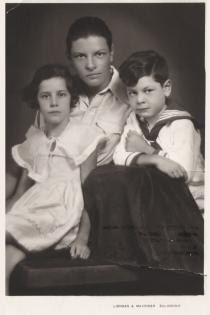

I was very close to my youngest brother and since I was a couple of years older I protected him. David was six years older [than I], so he didn't really mix with us, whereas Solomon and I, exactly because we were so close as far as age was concerned, had a special bond, a unique relationship. We used to play together in the neighborhood; we use to do all the nutty things together. I remember when he was young they always dressed him up as a sailor-boy or in Tyrolese clothes, because they were very much in fashion those days. As I mentioned, I always protected him and I allowed no one to come and tease him. If this happened I used to fight with the ones who teased my brother. I remember when we were kids our parents used to take us for excursions to Asvestohori.

David completed the American College 6 and attended the public high school in Thessaloniki and then went to France where he learned the work of the textile producer. The mother tongue of my brothers was Greek but also French and Ladino. They also learned English. None of them got married. My oldest brother fought on the Albanian front 7 during World War II, and Solomon only completed his military service after the war was over. When he was in Athens, during the period of the Civil War 8, a British soldier, who was drunk, hit him in the stomach. The hit was strong and my brother lost one of his kidneys.

My husband, Albertos Nahmias, was born in Monastir on 4th April 1915. He attended the Lycee Commerciale, a three-grade gymnasium with a technological direction. My husband became a fibre merchant. He speaks many languages: Greek, Serbian, Albanian, Italian, Turkish and German. During World War II his family and he escaped to Italy where they hid for some time. After the end of the war they all settled in Thessaloniki and after a few years, in 1949, we got married.

We had two children together: Ernestine, who was born in 1951, and Iossif, born in 1955. Iossif graduated from the Department of Biology at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and then he went to America for a Masters of Science and from there to Germany for doctoral studies in Biological Research. He worked in America, in Britain, and during the last four years in Iceland. But he returned to Greece because he couldn't stand the weather in Iceland. But his job was fantastic. So he returned to Thessaloniki and now he is doing some kind of research in association with the university. He is not married.

My daughter left for Israel, if I remember correctly, it was in 1979. She graduated from the Department of English Literature at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. She got married while she was living here, they had a child but they got divorced. Her first husband was named Iakovos Angel; he was a doctor. After her divorce she moved to Israel to work at a university there. In Israel she met someone, they got married and she remained there. She had a son from her second marriage; he is now completing his military service in Israel. Her second husband - whom she also divorced - was called Sam Hassid. He is teaching at the Polytechnics University in Haifa.

My children don't keep any Jewish traditions, especially my son. He is a citizen of the world; he has many dear friends in Germany, England and Iceland. And he avoids any interaction with the community here. Many of his friends from abroad come and visit him, even the Germans. They are not responsible for what their ancestors did to our people. Ernestine is also not religious at all. She keeps almost no traditions, not even at home. My husband and I, when we were younger, used to visit her in Israel. Now that we are old she visits us instead, almost once a year.

My family house, the one where I grew up, is on 25th March, Kritis and Marasli Streets. Before that we used to live just a stop away, on Vassileos Georgiou Street. Our neighborhood was the good one, with the three-story houses; you can see even nowadays the very few houses that are left. My family house was really nice and a big one but it didn't belong to my father. He rented it because he needed cash for his business. Our first house, the one I was born in, was on Mavromaton Street and it was close to the sea. When I was three or four years old we moved to our new house on Kritis and Marasli Streets. We went there because my father by then owned his own factory and he was partners with a Christian called Kazazis. Filotas Kazazis belonged to a very well known family from Monastir. So he was the one to make the laces and my father, along with his cousin, provided the name and of course the financial support. So the three of them became partners. But within six months Filotas died and his cousin Ioannis Kazazis took his pace. I remember he had a nickname: Vantso. So they became partners and they never disagreed on anything.

My parents never punished my brothers or me. My father didn't really interfere in the way my mother brought us up. But my mother was really modern and open-minded and didn't impose any restrictions upon me. She allowed me to go to parties and she kept saying to me, 'You are responsible for yourself.' I never had the need to lie. Since my father didn't interfere, my mother had all the responsibility.

My parents were not very religious and they used to go to the synagogue only during the high holidays like Rosh Hashanah. Thessaloniki had so many synagogues 9 when I was young. We used to go to the one near our house, 'Sarfati.' This was close to the sea but the Germans bombarded it. Sarfati means French, maybe someone called Sarfati was the donator. During the holidays such as Yom Kippur I remember our parents took us there and we played in the big yard of that synagogue. I remember everyone was fasting those days. They ate at six in the afternoon and until seven in the afternoon of the following day they didn't eat anything. Our parents kept this fast as well.

We always had a piano at home. My mother used to play. At that time all the girls coming from good and respectable families learned French and how to play the piano. It is funny. Playing the piano, especially among girls was a tradition. The first book in order to get the first degree, 'Becker,' was really difficult because we had to start at the age of eight. You have to start learning piano at a very young age because at this age your fingers are soft and tender. I kept on playing when I was in Athens. The daughter of my mother's friend went to the music school and this is why I wanted to go on with my piano studies. I still play. I remember my mother was playing only one melody. Always the same.

However, many girls who learned the piano gave up after some time. I had a cousin who had a piano degree and she stopped playing immediately after she got married. Maybe they forced them to learn it and this is why they eventually disliked it. I played all the melodies you can think of on the piano. Even now. This is a gift that a few people enjoy; I think that my fingers move automatically.

The elementary school I used to attend was a private one and it was situated in the area of 25th Martiou, where we lived. Initially I went to 'Natsina' and when this one closed I went to 'Zaxariadis' opposite the building of the Prefecture today. Nowadays this school is demolished to let the street pass. Zaxariadis himself was an excellent teacher and I remember we used to play in many theater plays there. And we had great fun because we used to change many costumes. We also had a kind of drama dancing: we used to dress as the flowers of the spring, and we used to imitate how flowers fell asleep in winter and how they woke up during spring. Our parents came to see us perform. When I later attended the Lycee nothing of that kind happened. And I hardly remember any patriotic plays at that time.

We used to have a dance teacher who taught us all the Greek traditional dances like 'kalamatiano.' We also had music lessons and we learned how to read the notes. Our music teacher was called Pavlidis and he used to play the violin. Some of the songs we were learning: 'In the afternoon there in my arms' and 'The birds were flying.' As a Lycee student I learned nothing of the kind. When I was a student we had costumes made for students to wear over our clothes. They were blue and the soft collar was white and we had two or three to change.

During high school I used to go to the Nuns from early in the morning till six at night. Classes stopped at some point early in the afternoon and then the school functioned as a baby-sitting place. Our house was near the sea so we went swimming, both boys and girls. But near the statue of Alexander the Great girls and boys were swimming separately. We used to go there when we grew up, at the age of sixteen, with our swimming costumes, which covered the body. I always liked swimming. Even now. And I remember I always went swimming with my friends. So my parents used to send us to the Nuns and we always managed to take some time off to go to the sea and swim, especially early in the afternoon.

Then the Nuns forced us to get some rest for three or four hours every afternoon. This was a torture for me... I couldn't be idle; I always wanted to read something. Anyway during the third year of high school I had a good relationship with the Nun in charge and she always sent me to get something and I ran away. I couldn't stand staying in bed all these hours without doing anything. Then in the afternoon we used to eat something at school and then the teacher we had at home used to take us from school to 'Luxembourg,' a famous coffee-shop and we had our lemonade - one for three people - and we played there in the yard until eight in the evening. And then we had to get home.

During the last high school classes they sent me to the Lycee de garson, - this was the Lycee for both boys and girls. We used to go to the Lycee every day, morning and afternoon, and we also went there on Saturdays. But on Saturdays we didn't have to be there in the afternoon and we didn't have to wear the apron. We, I mean the Greek citizens, attended classes both in French and in Greek. Those who were non-Greeks had to attend only modern language lessons in Greek, for three hours every week. We were also attending classes in ancient Greek, history, geography etc. At noon we returned back home and then from 4-5pm we went back to school.

I remember all students had an ID card to use on the tram, because that school was a long way from home. It used to take me half an hour to get to school because the tram was extremely slow and it had to stop many times.

My favorite subject was mathematics. We also had a fantastic French teacher, his name was France, and I was very lucky to attend his classes for four years. Yet our school wasn't as good as it used to be in the past. Our French director didn't care much. When I went there I was very weak in French and I remember the teachers allowed us to easily pass the classes. But after two years I managed to learn French. I remember my mother insisted that I learned that language. So she took me to a French school basically because she didn't want me to forget the French I had learned at home. But I disliked this language. She insisted though.

The foreign language we learned at school was English. But the English teacher wasn't really good and he used to punish us a lot. He wanted us to learn everything by heart. We had to memorize almost everything otherwise he gave us very bad marks. I was a student who was attending classes but didn't study at home much. Yet I listened carefully and this is how I learned.

When I was young we used to play football, there was a big open space in our neighborhood and we used to play boys and girls together. The balls were made of caoutchouc and I remember when we visited the Fair of Thessaloniki 8 every year they bought us a new one. We used to go to the Fair every year; it was a big event those days. We could see acrobats walking on ropes. It was great fun. We went to the stalls, they gave us promotion leaflets, and we also had an uncle who was working there. Our dad used to buy tires for the factory and I remember they used to give us a ball made of caoutchouc as a gift. At that time, the Fair of Thessaloniki was functioning as a kind of big music-hall, like a famous circus. I remember at that time even in cinemas there was a big show after the screening of a movie.

There was a summer cinema called 'Ilisia' in Aristotle Square. Three or four cinemas were located in that square, now you can only find modern coffee shops. I remember when I was twelve years old we still had that home teacher, I mean the French teacher who took us home from school. We didn't want this anymore and we disliked her. So, once my mom sent us to the cinema with her to see a movie. But for some reason she took us to another cinema to watch another movie, which was followed by a show and which was more expensive. As you can understand we returned home much later than our mother expected us and on foot because we had no more money left for transport. Our mother was worried sick and furious. Next day the teacher was fired and this is how we got rid of her. In normal circumstances we would have returned much earlier by tram. Instead we returned after midnight, on foot and without having any money.

I remember another time, when my brother was at the American College, and they took us for a walk to the Agricultural Faculty. My younger brother and I wanted to go there and find him. So we went on foot. And we made the French teacher - we called her mademoiselle - to take us there. We came back home very late...

When we were young we used to rent bicycles, we didn't buy them, we rented them because our father was really afraid that we might get hurt. There were stores that rented bicycles for a quarter of an hour. All our money was spent there. I remember I used to cycle up to Karabournaki and when I returned Vardaris [northern wind stemming from the river Axios or Vardaris] was blowing. I had a nice time: excursions with the school and with my friends.

I remember that in pre-war Thessaloniki the danger number one were the mosquitoes. We couldn't sleep at night because of them. And we also had bugs. Every two days they lifted up the beds to check if there were any bugs and they used to clean them with pure alcohol. The bugs were indestructible. Maybe they were surviving because the floor was made of wood.

We also had stoves made of clay and we used to burn wood. I told you about the problem with the mosquitoes. This is why there was a malaria epidemic despite the mosquito nets we had over our beds. We used to get ill quite often and we had high fever and they gave us quinine, the only available medicine at that time. In winter our feet were always wet and this is why we suffered from chilblains and we sat near the stove to get warm.

Before the war they measured our feet and they made us a pair of shoes every year. One pair at the beginning of autumn and one pair of white shoes every Easter. They had amiantus underneath. You know kids feet get bigger and bigger so they made us only one pair every year.

I remember when they gave us the anti-diphtheria vaccine. Our uncle was a doctor and one day - after a private discussion with my parents - they took us to his place for that injection. This is when I first experienced the 'anti-doctor syndrome' and this has chased me throughout my whole life. Those days this was a new vaccination.

When my brother got sick with scarlet fever I went to stay at my grandmother's place, I mean the second wife of my grandfather, because they had to take me away to avoid contamination. My grandfather died in 1936 and this is why the sisters of my father came to visit us. But unfortunately one of my cousins had scarlet fever and after two days I got sick as well.

I remember when I was young they used to put leeches on our grandmother's body to keep her blood pressure stable. They put them at the back of her ears. Some people were bringing them to our home in a bottle and I used to get sick watching this. This is why I left home that day and only returned late in the evening.

At that time the Campbell 11 pogrom took place and then the earthquake in Thessaloniki in 1933. I remember all the families were given tents and we were living and sleeping there for quite some time.

I remember the ceremony of bar mitzvah, which took place at the age of thirteen. This was an important ceremony for all the Jews in pre-war Thessaloniki. We first went to the synagogue and then relatives and friends came to visit us at home and we were treating them to sweets and ice creams. Guests were visiting us all day and for the first time in their lives the young boys were allowed to wear long trousers. During Easter, and generally during holidays, men were visiting friends and relatives and women used to stay at home. Men used to have their children with them and women were treating kids to this dark egg. And then they took it home to eat it. During holidays the following was a common practice: the men of the family paid visits to the women of the family.

Right after our summer vacations we used to go to Florina, a city in Northern Greece, located in the mountains. So after our summer baths at Thessaloniki's beaches we went to that mountain city. During the first years we went to a hotel but then after some time we met some people and we rented a house. How did we spend our days? In the morning we went to the nearby mountain called Pissoderi and then we were visiting the coffee shops playing backgammon and chess. This is how we learned all these games. Then in the afternoon we went for a walk in the city.

I remember Manthos Matthaiou also used to spend his summers in the area of Florina. He was the director of a famous hotel in Thessaloniki called 'Mediterrane.' He had a girlfriend, a very beautiful woman. They really liked my brother, so they invited him all the time to join them and I was so jealous about it. Matthaiou was killed during the Italian bombarding because he climbed up the terrace of his hotel to watch the airplanes but a bomb hit him. I remember he was a tall bachelor, a playboy. And his girlfriend used to wear make-up; she was a prostitute, a woman with weak resistances.

'Luxembourg' was a famous coffee shop in pre-war Thessaloniki. This was by the sea and it had an orchestra playing live music. It was situated in the area of 25th Martiou in Antheon Street. A famous artist called 'Tilda' used to play the violin there. People would go there at about eight in the evening, and I remember children like me were dancing on the dance floor. 'Luxembourg' was situated at the same place for a long time. Even after the war this coffee shop was in the same spot. After the war I also used to go there as a young lady.

When I grew up, I mean before the war, at the age of 15 or 16, I used to walk with my friends around the center of the city and especially so in the summer just before the war. We used to return home on foot to the area where we lived, Vassilissis Olgas. A famous cinema called 'Pate' was situated in this area. This was a cinema and a patisserie at the same time. We liked all sweets but especially pastry with cream and éclair with chocolate. In the same neighborhood another cinema, 'Apollon,' was to be found together with a dance club.

Every Wednesday and Saturday all the students from high school used to go to the cinema together. We went to the 'Apollon' cinema, which was screening two films. The second one was part of a series, a story to be continued like, for example, about a cowboy who was killed. The first movie was a romantic one and it was of a better quality, sometimes it was a musical. Most plays were American but others were French. My favorite actors and actresses were: Hari Bore, Teilor Paouer, Robert Taylor, Michele Morgan, Zan Pier Remor.

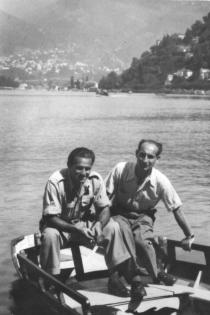

We used to go on Saturday nights to the city's nightclubs, I mean, of course, when we were a bit older. Just before the war started we were sixteen years old and boys used to come and pick us from our homes with the permission of our mother. In those clubs there was live music and everyone danced on the dance floor, mostly tango, the waltz and foxtrot. We used to go on excursions to Peraia but not that often. We also went on excursions with our parents; there was a small boat those days going to Peraia and there were some coffee shops there.

I remember when we grew up we went for walks in the center area, near Venizelos Street. Somewhere there a famous pastry shop was to be found, 'Galliko,' and we went there to have pastry and lemonade since we were not allowed to drink any coffee yet. We also went for walks near the 'Luxembourg' area, in Antheon Street. This was near our home. We used to go for walks separately, boys with boys and girls with girls. We were looking at each other and flirting, of course.

As I've mentioned before, I was attending the Lycee de garson, which was a mixed school for both boys and girls. But there was a Lycee only for girls. Those who were attending mixed schools took boys for granted; they meant nothing special to us and we paid no attention to them. But those girls who were attending schools exclusively for girls acted like crazy. I remember every Saturday they used to wear very eccentric clothes. Boys made no difference to us, and it was better this way. I think that mixed schools are much better.

Those days were very different than nowadays. Once a year, they used to make us a dress, which was the one we would wear on special days, and then we had our everyday dress. For example, we wore that special dress when we went to parties. As I said I was attending a mixed school and we were going to parties from when I was 14 to 15 years old every week together with our schoolmates. So every Saturday we put on our best dress.

Before the war Thessaloniki was full of Jewish neighborhoods 12. Especially in the area where I live now, on Vasilissis Olgas Street. Our neighborhood was a mixed one, both Jews and Christians lived there. Poor Jewish neighborhoods were supported by the Community; we called them 'koulivas' in Ladino, which means very poor huts. Palombita, a Jewish- Spanish mate of ours, lived in such a poor area. She was a young girl and her fiancé was named Massista, he was also Jewish-Spanish. His job was to visit local festivals in the periphery and demonstrate his strength on stage. For example, he was breaking chains and stuff like that. I remember that once Palombita sent him away, he came in the middle of the night, and he was shouting at our doorsteps: 'Palombita te cero.'

I remember when we were young we never visited the Vardar area, as this was a neighborhood with a very bad reputation. Rezi Vardar was a Jewish neighborhood that was built near the railway station. I think the Community supported it as well as two other impoverished neighborhoods: '6' and '151.' In the Vardar area one could find all those houses with the red light. I suppose ordinary people were also inhabitants of that area but I knew nothing about them. For me and my friends the city ended on Venizelos Street where my uncle, the husband of my mother's sister, had a shop with textiles called 'Cosmos.' This was the geographical limit for us.

All the central streets were paved. But the area where we lived, 25th Martiou, it was all earth and we used to clean the floor every day and especially when it rained. It was a disaster.

Before the war every family was celebrating the high holidays at home. I remember for Pessach we used to buy matzah from the Community. It was in big pieces and we used to put it in chests. There was also a big bakery owned by the Community on Vassileos Irakleiou Street. This bakery used to bake matzah for the Easter period. During Pessach you wouldn't find a single piece of leavened bread in our houses. Of course all that happened before the war. I remember when the Germans entered Greece we stopped eating matzah and we kept it because we were afraid that we would not be able to get any more. From the time the Germans came I believe we stopped keeping the traditions. We keep nothing now...

We had a good time with our neighbors and there was no tension between us, anyway our neighborhood was a mixed one. Only some bad boys were making fun of us and they called us 'tsifoutides' meaning stingy and we called them 'giaourtides' [yogurt men] from 'gkiaourides' ['gkiaour' was a Turkish nickname for Greeks]. I have no idea were those rascals came from.

I remember the customs we kept before the war. For example, before New Year's Eve [Rosh Hashanah] we had to practice 'kapara,' meaning sacrificing. We used to bring cocks home, which were kept on the balcony of the kitchen. We waited until the night of Protohronia and then the hahamis came. He used to sit on a chair and my father put a ribbon on his head, called 'kapara' and he slaughtered the animals. Afterwards we had to offer them to a poor family. It was forbidden to eat the sacrifice. And I remember we knew some poor families and they used to visit us every Rosh Hashanah to get the slaughtered animals. You know Jewish families before the war were so extended and we had so many relatives that during feasts we ate at home. We used to have friends within our family but we also had friendships with our neighbors. Anyway until the war we were all together.

At that time we were friends with the boys from Kostandinidis School. During the occupation, I mean during the war with Italy, we had rented a house all together. This was a shelter like our school, the lycee. Since our parents were very worried and didn't allow us to go to other neighborhoods we spent our time there. We had rented this house as a family, the so-called Voga's house, but four other families were living there as well. When the alarm was on we were not allowed to be away from the house. So we found ways to spend our time there as pleasantly as we could.

This house was situated near the sea, on Vassileos Georgiou Street, opposite the Lycee, and now it doesn't exist anymore. It was a two-level house with a yard and a garden and in the yard I remember we used to play volleyball. The father of Boubis Vogas was very rich and his sister, Mahoula, had married a rich guy called Georgiadis who owned the FIX industry. Boubis' mother was dead and his father was almost deaf. That's why all the parties were taking place at his home. I played the piano, we danced, and we played modern records on the gramophone. We used to dance tango, the waltz, and modern dances like rock and 'gianga.' We also liked light Greek songs like 'I'll take you away' but not 'laika.'

I remember most of my friends from Kostandinidis School: Moris Alien, Arthur Mortician, Thanassakis, he was the son of Kostandinidis, the director of the high school, Bernard Benveniste, Haralambos Psaltis, David... Christians, Armenians, Jews all together. We were friends and schoolmates and there was no discrimination among us. Arthur Mortician died eight years ago. After many years he rented the apartment downstairs. I remember one day I had met him on the street and I rented this apartment to him because he was a good friend and we played cards together. We played 'biriba' also with Loucie, his Armenian girlfriend, and Ismini Ioannidou. Boubis Vogas had a tragic death: he drowned while he was diving for fish and as I remember, he died quite young. This happened in Athens.

There was no radio in our house before the war, and not even a telephone, although you could find some radios in Thessaloniki from the 1930s onwards. My mother's brother, Alfredos Beza, owned one. My uncle was really modern, he had a motorcycle, he went on excursions and he was a climber. He joined the mountain climbing club and I wanted so much to go with him whenever he went to the mountains.

My uncle didn't get married until he was 48 years old. I will explain how it happened: At that time my mother used to invite many people to stay with us, in our house in Athens, and at some point her cousin, Claire Matalon, the daughter of Doctor Matalon arrived. She had just returned from a concentration camp. And at the same time when she was staying with us my mother's brother came to visit us. So this is how they met and fell in love. According to Jewish tradition it is allowed for first cousins to get married, so they got married. Claire was married when she left for the camp. Fortunately her daughter hid in Athens and eventually she was saved, but Claire took her son along. When they arrived the Germans said to all women with little children, 'Leave your children to the eldest and the Red Cross will come and save them.' Unfortunately her little boy was only seven and they killed him.

Claire and her sister made it because they were knitting for the German doctor of the camp; he took them to the hospital. They managed to survive but of course they were in a very bad condition when they returned. They had been infected by typhus. My cousin told me how they forced into hot water all those children that were born in the camp. You know, pregnant women were also imprisoned.

When we first heard all that we couldn't believe a word. We though our relatives, our people, had lost their minds. We used to say, 'They are crazy.' I remember the first one who returned to Athens was called Assae; he was a piano player called Michel Assae. He was saved together with his sister because they were members of the orchestra of the camp. As time went by more and more returned.

What was happening in Thessaloniki with the climate the Germans were cultivating against the Jews was definitely a bad sign. This is why my father decided that we should move to Athens to hide. So we left Thessaloniki on 28th February 1942 just before the imposition of the Nazi measures on 15th March. The fact that we managed to escape was exceptional luck.

At that time it was very difficult to find a house to rent in Athens. But after searching we found a place, rented it and went there to hide. We had a Christian landlord and when the Germans started searching the house for Jews we left this house and returned when the situation had calmed down.

When we returned we found living in our house some women who had good relationships with the Germans. They had occupied our house and they were living in it. After the war we took the matter to court and we got half of the house. Later those women collaborated with the English. What can you say? Those women were going where the wind was blowing. Women with a very elastic morality. I remember they used to invite me to the parties they were organizing.

They kept another house in Halandri, on the outskirts of Athens. Things were different than they are nowadays: at that time all those who owned a house away from the center of Athens wanted to find one closer to the center.

Anyway, for some time we stayed together with those women, we lived under the same roof but we divided the house. Then, with the court decision we practically managed to send them away. This house is on Kefallinias Street near Amerikis Square. Later we bought the house from its owner and now my brother lives there.

When we were in Athens we met a woman called Teresa, maybe she was German- Jewish, and I remember she had an affair with someone from the police force, someone very high in the hierarchy. We used to invite her to our houses and everyone was flirting with her. She had provided us with false identity cards. She was quite mature in age but she had done something like a face lifting in order to look younger. The results were very bad though...

In Athens we had been provided with false identity cards, Greek identity cards. They called me Aggelidou, derived from my real surname, which was Angel. My whole family had similar identity cards. But they were perfectly valid because Teresa had issued them in the police force. But of course we had no card for the food distribution and, you know, in Athens during the war there was a great hunger. Here in Thessaloniki and especially in the periphery things were much better.

I remember my brothers left the house and they were searching for almost two hours to get us something to eat. At the beginning the situation was very difficult. But as time went by things got better. You could find something to eat. We mostly ate legumes. Every noon and every evening a big casserole of legumes. Next day beet roots with garlic sauce, next day black spaghetti, next morning honey from grapes that we bought at the black market. We also bought German bread at the black market.

My mother didn't seem to be upset. When we went to Athens we hid separately in three houses: my big brother in one house, my parents in another and my little brother and I in yet another. And when things got better we moved all together to one house. I must tell you that we were hidden by Christian families, our friends. Initially my youngest brother and I went to Mavraki's place; he was a factory owner. My mom went to a neighbor opposite and my brother and I went to the house of Gavalas, who was my father's friend. He lived in Palaio Faliro. At the time when we were hiding the Germans bombarded Piraeus. But I must say that they respected Athens and didn't throw any bombs. Of course I cannot say the same for Thessaloniki.

When we were hiding in Koukaki in Athens I remember the Germans were chasing the partisans all night. You know, revolutionists. There was resistance in Athens, ELAS 13 partisans were fighting in the streets. People were really afraid of what was going on and they were locked in their houses. So there was great resistance in Athens. But nothing of the kind was happening in Thessaloniki. Locked in our house, we used to hear the gunshots. There were rumors that the liberation was near.

When we were hiding in Athens some people came and blackmailed us. My dad was going out all the time, talking to all the people in Koukaki so that's probably how they learned about us. I remember we had rented a house from a spinster who had an affair with a pensioner. I didn't like his face at all, I have a kind of intuition with people, and I told my mother so. She was very angry and said to me, 'Stop the nonsense.' But I was right. I remember we left from the kitchen in order to avoid those people and went to the terrace and this is how we managed to escape.

I couldn't say that our life in Athens wasn't good. Next to our house there was a theater and every week there was a new play. We used to watch classic plays and once, when we returned home, we learned about those blackmailing us. My father gave them gold pounds but after 15 days they came back. This is why we went to hide in a neighbor's house for a few days. I was watching and I saw no German road block and after this incident we left this house forever and we stayed for a while in the house of my dad's friend. When the blackmailers knocked on the door we had already left our house.

As I have said, we stayed at Farantatou's place and we rented a room in his big house. He owned a big house: the bottom floor belonged to someone else. So we rented a room in Farantatou's place and another from the one who owned the bottom floor. I remember at that time we used to pay the rent by giving them oil, a certain quantity of olive oil.

Thank God we had good friends in Athens who gave us shelter whenever we needed it. They managed to hide us for a whole year. After we left Farantatou's family we went to a place near the French Academy. Our friend Pantelis found a room there for us. This was a friend of my eldest brother. Pantelis also helped a communist and an Italian to hide there. Imagine: a communist, an Italian and some Jews under the same roof! The last place where we lived in Athens was also near the French Academy. Rose Milliex lived on the top floor; I remember he was married to a Greek woman called Tatiana Milliex. We stayed there until the liberation. So we changed four houses within a year.

We heard rumors about what was happening to our friends and relatives in Thessaloniki. We knew that the Germans were cutting them off in ghettos and they were soon deporting them. We didn't know exactly what was going on but surely we didn't like the behavior of the Germans. Exactly because we felt that things were bad, we hid in Athens. As for the Athenian Jews: they had to register at the synagogue every week. And one fine day they caught them and sent them to the camps. Our people were really surprised because they hoped that they would enjoy a different treatment, and nothing would happen to them. But we were afraid and this is why we were hiding.

Our relatives from Thessaloniki were telling us about all the horrible things happening there. When they returned from the camps, I mean after the war was over, at the beginning no one believed them. Everyone was saying, 'What stupid stories are you making up?' And really, how could anyone believe their stories? Anyway...

I continued to play the piano but the one we had in Athens was in a bad state because at some point it caught fire and we poured water on it. The one I have now in my house is a 'Gavo.' This one is really old. We sold the one we had in Athens and we bought this one. It's a fine piano, a very nice piece. I bought it from a friend who inherited it but she didn't need it. This is much better than the one I had before.

Back in Thessaloniki we still owned a factory and our Christian partners were sending us products to Athens. Those that went to Athens never came back because that city offered better prospects. My family never wanted to return to Thessaloniki. After what had happened... But my lucky star brought me back. I didn't want to set foot here again but sometimes things in life come quite unexpectedly... At the beginning I was very unhappy. I cannot say that I don't love Thessaloniki but I never wanted to return here.

During the war I remember every Monday there was a concert of classical music at the theater of Irodis Attikos. I was also attending lectures on art and speeches by Papanoutsos. Since it was forbidden to walk at night we were partying all night and in the morning my friends and I were going for excursions.

In Athens every Monday we were going to the theater and we also attend concerts of classical music. I remember we were sitting at the rocks of the theater listening to this music. I must tell you that even though it was a difficult period, the period of the German Occupation, the theater was nevertheless full of people. It was a time when we had so many interesting things to do. And watching theater performances was certainly among our priorities. I remember Rena Vlachopoulou, now known as an actress and a comedian, who was a singer back then. She used to sing a song that goes: 'The flower you have in your hair.' I also remember Oikonomides who was always performing the role of a civil servant.

The most famous theater in Athens was 'Kotopouli' in Omonoia Square. When I first moved to Athens musicals were the most popular kind. I remember a musical with the famous Nana Skiada, which was really a success. And the song she sang was: 'Salt and Pepper.' This was also was a great success, or so I was told, because I didn't manage to watch it myself.

The parea in Athens was really big and the leading figures were two doctors. We were 19 and they were 25 years old and they wanted to hold Bakalorea so they could be able to go to France and go on with their studies. They were the organizers of our little group. It was very nice. We were organizing lectures and every Sunday we went on excursions. We were visiting many places on the outskirts of Athens but we avoided the seaside because were afraid of the German bombing. You know the Germans had already bombed the harbor of Piraeus. We were really making fun of the whole situation although it was very scary indeed.

We used to go to Penteli in some small buses called 'gazozen' that were using wood instead of gas as a fuel. Cars were very rare at that time. And we put our suitcases on the top. These buses were more like mini buses and we liked sitting on the top of them instead of sitting down in our seats. If I remember correctly, we rented them. We had the permission of our parents. Especially my mother was a very open-minded person. She said to me, 'You are responsible for yourself,' and she let me go out wherever I wanted. But my mother had brought us up with very strict principles, almost puritanical...

The leaders of this friends' club we had organized belonged to the left wing. One of them was called Giorgos Kelaiditis and he was writing for a newspaper. He came from a very rich and educated family from Constantinople. The other guy was called Giannis Ioannou. The discussions we had were not political but of an artistic nature. Twice a week Kelaiditis used to invite home people of all kinds and he used to lecture us. Most of them, as I have said, belonged to the left wing, and they where trying to pass the exams of Bakalorea in Athens, and the majority were Thessaloniki Jews. But of course Greeks joined our club as well. The Goulandris family and other Greek tycoons were also joining these French classes, i.e. those who spoke French. By then the pogrom had not yet started, that's why we still had our own identity cards and everyone knew that we were Jewish.

I remember when the Germans came and the issue was raised Kelaiditis, who was organized in the resistance and was a doctor said, 'Whoever needs to hide I am going to help.' And he did. He helped many people, for example he put some girls in hospitals, pretending they were nurses. I never went to him for help. My parents had taken care of everything and had found a shelter to hide. All the members of my family had new identity cards issued; I really don't know how but I do know that these identities were valid. The only thing we missed was a coupon for food but we could find something to eat at the black market anyway.

Of course my father had stopped working at that time and closed down the shop he owned in Athens. But we still had this shop in Thessaloniki, together with our Christian partners who were working during the war. Yet we had no contact with them during the years 1943-1944.

We had taken with us to Athens all our savings, in Greek money that was constantly devalued. So we started changing it into pounds that we used at the black market and this is how we managed to survive. But we soon ran out of money. In the end the money was so much devalued that one English pound equaled 1,000,000 drachmas and the next day 2,000,000 drachmas. I think the pounds were changed at the black market but honestly I don't know for sure. You know these were not stories shared with little kids. Our parents kept all the sad things that were happening to themselves...

So when the war was over we were in Athens hiding in a place in Sina, Arahovis and Akadimias Streets, this was the last house we were hiding in. We wanted to get back home but almost immediately after the [Great] War the [Greek] Civil War started. We were living in the center were the English were, opposite the Anglican Church. I remember the English were hiding in their church and from there they bombarded the Elasites, the guerillas of the left. Every day it was possible to walk freely only for two hours and then you had to hide at your home because the streets were turning into battlegrounds.

Whenever the battles ended people used to get out of their houses in order to find something to eat. And it was so difficult to find something to eat! Everything was so expensive, we couldn't afford it! We bought the necessary things at the black market near Kolonaki by exchanging goods for olive oil. Olive oil was so expensive you needed several pounds to buy just one liter. Well we bought anything that was available on the market. At that time you really had no choice. Some people even lacked fuel to cook. I remember we used to take our food to the French Academia and we cooked it there. Things were really difficult.

I remember once a truck full of dead people was passing by. And the only thing we could do was to pull the curtains... This entire situation lasted two or three months. The English were at the center of Athens and the guerillas were all around.

My father said nothing about the situation and his only comment was, 'We have to be brave.' He was a very optimistic person. He used to say, 'The war is going to be over soon. In one month we will be free.' And we replied, 'Dad you keep telling us the same thing over and over again.'

Well the most tragic of all was the fact that from one war we went right into another. The Elasites were armed and they got this opportunity. They wanted to take over Greece. But there was an agreement that they should have kept. I remember the day of the liberation. I mean when the Germans left. We rushed out into the streets and we were enjoying the taste of freedom but soon after that the Elasites were walking in the streets singing: 'EAM 14, ELAS' and those that liked the monarchy were singing: 'The King is coming.' Gradually the guerillas became more and more aggressive. In the end only the guerillas were walking freely on the streets and the Civil War started. We could feel this tension: the guerillas of the left on one side and the warriors of the right on the other.

When we were hiding during the Civil War the guerillas were looting store- houses. But I must tell you we felt like paralyzed during the Civil War because we didn't know what was going to happen. In Thessaloniki communists were in charge of the city. In Athens things were different; we managed to get rid of them. When the Civil War ended the communists left Athens but in Thessaloniki things were different. There was still this feeling of uncertainty. All that time, even after I got married and returned to Thessaloniki in 1950-51, we still felt this danger that the Russians would come and take over Greece, and it would eventually become a communist country. This rumor was in the air for many years. Even when I got married in 1949. We were afraid that the Russians would take over Greece. We had the feeling that this could happen anytime. This was the climate of the Cold War. And the guerillas of EAM had taken over Thessaloniki. My mother's sisters were so much affected by this political uncertainty that they decided to leave Thessaloniki and immigrate to Mexico. They were already married to two brothers and they all went to Mexico.

My cousin Zermen Koen introduced me to my future husband in 1948. We were only dating for a short while. We used to discuss everything to see if our ideas matched. I was trying to understand his personality, but I must say that he was an honest man brought up with morals. I had heard about Albertos that he was honest and very capable. My mother's sister had married someone from his family so I got to know about him. And I remember my aunt saying, 'He is the most capable, clever and nice in this family.'

At that time we were going through a kind of brainwashing: 'You have to get married.' This was a common mentality at the time; I mean to get married at a certain age. I think that Albertos wasn't really thinking about getting married but his mother kept saying to him, 'What is going to happen? You have to get married; I cannot take care of you anymore.' It was a kind of brainwashing. My husband had some friends before getting married, Jewish and Christian friends, like Giorgos Slavis, Sam Saltiel, and others that had promised each other never to get married. And one fine day they found out that Albertos was engaged. He was the first among the parea to get engaged and all the others followed into his footsteps. I remember when we met, the first night we went to 'Bouki,' a nice tavern near the new sea- side. We used to walk together a lot then.

Our parents forced us to get committed but we kept telling them, 'We have a nice time together. We'll see.' But they insisted that we should get engaged. At that time, especially with arranged love affairs, after a short time you had to say whether you wanted to go on or not. So after all this pressure we finally got engaged and I went to Athens to get ready for the wedding. The wedding took place in Thessaloniki a few months later, on 6th March 1949.

The engagement took place at my mother-in-law's house, and that day the house was full of flowers and relatives and friends were coming to visit us all day. This was the custom. We treated them to almond sweets and sweets called 'bezedes.' Our dowry - sheets, night dresses - were all over the house because they had to be shown publicly.

So we got married on a Sunday, on 6th March 1949, in the big Synagogue 15 on Suggrou Street and the same day my daughter's future mother-in-law got married. A lot of marriages were happening then. I mean after the liberation, a lot of group marriages 16 took place. Another couple was to get married immediately after us. The son they gave birth to was to be called Hassid; he later became the future husband of my daughter. I remember the couple had complained because he had booked the synagogue first and they said, 'You got all the flowers.' Well the future mother-in- law of my daughter was a difficult woman. At that time one marriage followed the other.

All the family got together after the ceremony. The very same day it snowed in Athens so we didn't manage to get there as we had planned.

I had my wedding dress made at a dressmaker's in Athens. She made me very nice dresses; she was haute couture. Her name was Elli Perigiali and she was married to Notis Perigialis, an actor always playing the nice, naïve person. He played in the film 'Lola,' I think he acted in all the films of the time. So Elli made all my dresses and I must tell you she was really good at it. I took her with me when I went to Athens and she stayed with us for fifteen days. I wanted her to make a suit for me but she didn't have the time. For the wedding she made also nightdresses and robes for me.

I remember I kept my wedding dress several years after my marriage but then I altered it to an ordinary dress. I remember I had the color at the bottom changed. Underneath the wedding dress there was a material to lift the hips because I was really thin at that time. But I had a fantastic silhouette.

I remember Elli and I used to alter my brother's suits so that I could wear them. We didn't throw out anything. At that time we used to wear trousers and short pants only when we went on excursions. And in Athens we were playing tennis and we used to wear shorts. I remember I had made one after a pattern from a French magazine. I used to make many things myself and I kept these shorts for many years. They were made from a good thick fabric.

At the beginning Elli knew nothing about our Jewish identity. Then she found out and we became very close friends. She was a very nice person; that's why she was so popular. She had a very good taste and she knew how to make beautiful dresses. When I first met her she was very young and she was paid for a day's work. Then she fell in love with Notis, who was also a violin player and a poet. But her mother was against this marriage and rejected him. Elli was so angry that she left her father's home and went to live with Notis. Her house was in Nea Smirni. At that time she was a pioneer, an economically independent woman.

As I told you Elli became a very good friend of mine. Whenever I gave a party she was always invited. But my mom thought that it wasn't proper to have a friendship with someone who works for you. I guess we had more democratic feelings than my mother had. After I went to live in Thessaloniki we kept in contact. I also introduced her to my dressmaker here and they started working together. After the war Aggeliki, my dressmaker in Thessaloniki, and Mattoula, her sister, transformed their apartment on Vassileos Georgiou Street into a fashion house. Aggeliki was talented and self-trained. Her daughter was later married to someone called Siapikas, who was a doctor. Another famous dressmaker was Kiouka. These were the most famous in Thessaloniki.

As I've mentioned before, after the wedding we went to my mother-in-law's house to celebrate. All the family gathered there, we had dinner together and later we left to sleep in a hotel that night. We had planned to go to Athens for our honeymoon but the weather on 6th March that year was so bad. It was snowing so the airplanes couldn't fly that day. So we stayed at the hotel 'Pallas' during our first night and the next morning we managed to get a plane and fly to Athens. Times were difficult then and you had no options really. So we went to Athens and we stayed there for eight days. We celebrated our marriage in Athens as well. All the family came to visit us.

During the first years of our marriage we stayed at my mother-in-law's house. Then, after some years, we exchanged it for an apartment. This house was like the old houses: semi-basement, first and second floor. It was a beautiful house with a big corridor leading to the rooms. This house had a garden as well with flowers and many trees. I must tell you that the Jews didn't give a house as a dowry to married girls. I think this was bad. The father gave her some gold pounds to start, and actually he gave them directly to the groom. Then the groom used them for his business. This was a tradition. I believe people at that time were more honest. If your marriage was arranged you had all the information you needed about the qualities of the groom. Especially if he was working in the market place. This way marriages were safer in a sense.

During the first years after our wedding we lived all together: I mean Albertos and I together with his brother's family and his mother. And we stayed at my mother-in-law's house since we didn't have enough money to live alone. I remember my husband's brother had said, 'I will pay the rent, go and find a place for the two of you,' but my husband didn't accept his offer. Anyway this house was quite big and one room was where my husband's brother, his wife and his child lived, while Albertos and I lived in another room. Of course my mother-in-law had a room for herself. We lived all together for four years. Certainly we didn't have the money to live on our own so we decided to live all together and share the expenses.

The rest of the house didn't belong to us because other people lived there. You know after the war you couldn't send away those people who had found shelter in your own house. This was a very traumatic experience: having a house but not being in a position to use it exclusively for your family. This was called 'enoikiostasio' and was a common practice after the war. And those people were living in our house without paying any rent to us and still we couldn't kick them out. In some cases they were paying a ridiculous amount of money. This was going on for many years after the war and the house prices had fallen because at that time no one bought a house since there was no money.

In that house my mother-in-law cooked and we had two maid-servants. At that time you couldn't manage all the housework, it was really heavy. I remember there was no electricity and we had to use coals. Of course in our case there were so many people and therefore there was so much housework to be done. In the meanwhile my sister-in-law, who already had a boy, delivered twins, so she had three children to look after. After two years of living together I got pregnant so things were getting more and more difficult.

Here in Thessaloniki everything started from zero. At that time my husband had his own fibre store on Syggrou Street and he really started from scratch. I insisted that he opened a store in Athens but he was not ready yet. But we kept visiting Athens quite often since all my relatives were in Athens. At the beginning of every week he used to buy a specific quantity of fibres, sold it and then he paid for it at the end of every week. There was no cash available at that time. Everyone had run out of money. But my husband had a good reputation so the factory that produced the fibres gave him large quantities for which he could pay later.