Albertos Beraha

Athens

Greece

Interviewer: Annita Mordechai

Date of interview: March 2007

Albertos Beraha has a childlike smile and a round face. He lives in a beautiful apartment in the suburbs of Athens, with his wife Deniz.

They live close to two of their daughters and all of their grandchildren; the third daughter visits them from Paris whenever she can. Around the house there are pictures of their children, grandchildren and family.

Albertos is a retired civil engineer but spends a lot of time in his study reading. In his study he has a big library with books on history, geography and politics.

There is a piano as well for their grandchildren to practice whenever they visit. His memories were always charged with emotion and he helped me gain a better understanding of life in Thessaloniki and the importance of family ties of Jewish families.

Whenever I went to his house, he always welcomed me with a smile and a plate of fruit.

- Family background

I don't know very much about the origins of my family or my great- grandparents. In the past, the origins of the family were traced according to synagogue, and my father used to say, 'del kal de los pescadores,' from the synagogue of the fishermen. Now, how we became fishermen from Sicily or whether they were real fishermen I have no idea. That is what he used to say though.

The actual site of the synagogue named the 'kal de los pescadores, which my father claimed was the one my family had its origins in, was never one I knew in the town of Thessaloniki. It probably no longer existed when I was born but that is where we originated from. It seems that back then there were different congregations around Thessaloniki, all said that their origins were from Spain but, who knows, it could have been Portugal.

My grandfather on my father's side was called Abraham Beraha and my grandmother, my father's mother, was called Mazaltov, nee Arditi. My grandfather died when I was three years old, so that would have been in 1928. I used to go to him every Saturday to get his blessing; he would put his hand on my head and say a prayer.

Grandfather Abraham was a shochet, which means a butcher. His education was religious but I don't know where he got his training. I know he was born in Salonica, but I don't know when. He was a religious man and his mother tongue was Ladino or Judeo-Spanish 1.

My grandfather Abraham had a brother who was missing; he had left Salonica. After a long time they discovered his whereabouts and realized he had converted to Islam and had become a Turk.

I can't remember his name, but I know that they found him in Constantinople [today Istanbul] where he held a high position in the staff of [Abdul] Hamid [(1842-1918): 34th sultan of the Ottoman Empire]. Hamid had made him director of the Regie National de Tabacs, the company that dealt with the transport of tobacco in Turkey.

My grandfather Abraham was in a difficult economic position having to sustain seven children on his shochet salary, so he used to go to his brother in Constantinople now and again for some assistance. The brother would give my grandfather a pouch of golden liras and he would come back to Salonica.

At some point the brother in Constantinople asked to meet his nephews and so my father, Carolos, and my uncle Morris, the oldest of the four boys, went with their father to his brother.

What is interesting is that this uncle had a daughter called Halide Edip; maybe you have heard of her? [Halide Edip Adivar (1884-1964): Turkish novelist and feminist political leader, who also served as a soldier in the Turkish military during the Turkish War of Independence.]

Halide was part of the close staff of Kemal 2; she was in the group of people who started of the Young Turk Revolution. Everybody knows her name but no one knows of - or if they do they don't speak of - her Jewish descent.

Now about my grandmother Mazaltov: I know she had three sisters, Myriam, Alegra and Eleonor. Mazaltov also had a brother, who was a 'troxodromikos' and worked for the Troxodromikon Electric Lightning of Thessaloniki in 1918. My father Carolos looked after all three of his aunts. He maintained many members of the family; he had his sisters to take care of as well.

Carolos's sisters were named Alegra, Lukia and little Rebecca. They were married: Alegra to Josef Brudo from Thessaloniki, Lukia to Levi Tazartes and Rebecca to a man called Cohen. Even though I have a picture of him, I don't know his first name.

Alegra, her husband and daughter, who now lives in the USA, and Zakinos, the son of another sister, were receiving some sort of help from Carolos. The structure of the family then was such that they didn't let anyone fall by the wayside; my father would take charge after any misfortune.

Carolos also had three brothers. Morris, his older brother, who was born around 1894, died some time in the 1960s. My father's two other brothers were Elias and Jim; Jim was older than Elias, who was the youngest of the family.

Jim and Morris were living in Athens before the war began. Elias got away from Thessaloniki on a boat and my Grandmother Beraha left on the train, as we did. The fact that she survived is the epic of the family. We all left Thessaloniki and came down to Athens and she came along. She only died after the Liberation, at some point in 1947.

My grandfather on my mother's side was called David Saporta and he was originally from Serres. His wife, Ester, was born a Saltiel. Grandmother Ester died in 1931 from a typhoid epidemic that was rampant in Thessaloniki.

I know that Grandfather Saporta died in 1912. He had a large family. He had two wives; from his first marriage he had two girls and after his first wife's death he married my grandmother Ester. She was a widow and had a son from her first marriage called Benveniste. So they had five children all together.

David Saporta was an employee of a pharmaceutical company and was a respected person; however he died early and left his children orphans. I really don't know much about his education but I know his mother tongue was Ladino. I think he may have spoken some French, as the company he worked for was a French one. He wasn't religious.

It was my grandmother Ester who was the most religious of all of us; she used to take me to the synagogue every Friday night to light a candle and to put some oil. She took me to a synagogue near the 12th state elementary school around Analipsis. My grandmother lived with us in the house.

My grandmother would also take me to the working class neighborhoods in Thessaloniki. There was a big fire in Thessaloniki in 1917 3 and almost the whole town had burned down, so lots of people were left homeless.

That was near the end of World War I, and when the British and French troops left the city their deserted camps were turned into refugee housing. Even when I was a child these refugee camps still existed; they were '151' 4 and No. 6 and Baron Hirsch 5. Only Jews lived in these camps and my father, who was a member of the Community Council, was in charge of this section.

David Saporta, my grandfather from my mother's side, had a brother who worked in the same pharmaceutical company; he was one of the people in charge of collecting the natural resources for the company. He would go out in the countryside of Macedonia in order to buy opium and saffron.

Since he went out in the countryside year after year he was well known in the area. However on one occasion he was out in the countryside touring and was caught by the 'komitadgi' [Bulgarian nationalist revolutionaries]. The story goes that they had a fight and he was shot and robbed and left in the wild to die.

Grandfather Beraha I saw every Saturday, he was very old and all he did was give me his blessing, he would put his hand on my head and pass the blessing on me. That is all the contact we had. I don't really know if he was a calm person but I remember him being serious, I don't have a particular memory of how he dressed.

He and my grandmother didn't stay with us; they had their own house. They didn't live in Jewish neighborhoods because after the fire of 1917 Jews and Greeks were living in mixed neighborhoods. We all had lots of Christian neighbors and generally got along very well with them. It seems we only had problems with the refugees, that is, the Greek refugees from the Asia Minor Catastrophe 6 or Destruction of the Greek Army in Asia Minor in 1922.

Neither of my grandmothers wore the traditional Sephardic dress, they were both dressed 'a la franca.' They both had long hair and always wore it tied up.

My family was my mother Mathilda and my father Carolos, my grandmother Saporta, my aunt Sarah, my mother's sister, and me.

- Growing up

We moved houses a few times. I don't have any memories of the place where they lived when I was born but I knew where it was as it was in the same neighborhood.

We had a family doctor called Dr. Valanidis. He was a Greek doctor who had studied in Italy. He had a beard and he had a bad leg and would walk a bit strangely. He was really nice.

Palaion Patron was our address and then Alexandrias and then another one was on Petros Sindika Street. That last house was an old Turkish house, really big and well preserved. It had lots of wooden features.

There are two things I remember very vividly, once when there was an earthquake in Arnea, and the whole of Thessaloniki felt it, I was in my grandmother's arms and she was washing me as it was Friday evening when the entire house started moving, and we all had to go downstairs and there was a big tremor.

We returned to the house at night to sleep but there were smaller tremors all night and as the house had double doors all night we could hear the 'tak tak tak.' The doors kept on banging; the house was old as I said.

I remember that in the corridor we had a piece of furniture, a buffet, and I had been given a toy car with lights that turned on and off, and I ran up and down the corridor playing with it, always though with my grandmother at my side protecting me.

In that big buffet my grandmother stored her sweets in ceramic pots and now and again the ants would discover them and she would have to empty them. On Saturday families used to visit each other. My cousins and aunts would come to see my grandmother on Saturday and later when she died they would come to visit my mother.

When you entered our house on Sindika Street you saw an open space and all around it there were the rooms, on the left I think was the bathroom and the kitchen. It had four or five rooms. My mother Mathilda and my father Carolos, my grandmother Saporta, my aunt Sarah and I lived together in that house. I shared a room with my aunt Sarah.

The house had electricity and running water. What was typical of the time is the way the bathroom was heated. We used to heat it up with wood. There was a metal structure with pipes that ran through it; it had two sides and that is where we lit the fire to warm it up. We used to do this not only to heat the water up but for the bathroom to warm up so you wouldn't catch a cold.

The house was heated by heaters called 'salamandra.' Each had a small window where we constantly added charcoal. However these were not enough for the whole house to be warmed up. There was a big heater in the living room that was part of the dining room, which was where the family met to eat and sit together. All the other rooms had wood burners, which were used to warm up the rooms only when someone was ill.

Winter was hell. I remember the cold weather very well, and the house was really cold. We didn't have anyone staying with us at home to help with the housework; I think we had a lady coming to help with the washing. At one point only we had a girl from a village who came to stay with us. I never had a nanny as we lived with both my grandmother and my aunt Sarah who looked after me along with my mother.

The second house, which we lived in before moving to the renovated Turkish one, had a beautiful garden that was on Koromila Street. It was a beautiful house; my father liked beautiful things, so he brought flower seeds from Holland. He wasn't the one taking care of them though, as we had a gardener.

The house also had a beautiful veranda looking onto Koromila Street. At some point my aunts and uncles stayed on the first floor of that house, but then we moved into the renovated Turkish house.

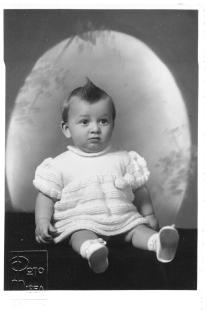

My father's full name was Carolos Beraha; he was born in 1898 in Salonica. He didn't live anywhere else but in Greece, and died in Athens in 1982. Appearance-wise he looked very much like me; he was a well built man but not too tall.

My father wore a 'republica' style hat. I even remember the brand: they were Italian made, very expensive, and were called 'Borsalino.' He had many of them and changed them according to what he was wearing. These hats actually survived, my daughter Nineta has them at her house, but I haven't seen them for a while.

Anyway, my father didn't have ginger hair; he only became ginger during the occupation when he let his mustache grow. He was a loud and talkative man. I am not sure if he had a sense of humor as we understand it today, but he was popular and had lots of friends. He read the newspapers at home; in our house there were always French newspapers. He had finished high school at the Alliance School 7. Everyone in Salonica spoke French back then as many people finished the Alliance Schools, which were spread throughout the Middle East and Persia.

My father was a currency broker; for example he bought and sold Russian rubles and would exchange them for liras in Salonica and then sell them in Athens. My uncle Morris, who was in Athens, did the same job as my father. My father had a Jewish associate; I don't recall his name. My father was very sociable; he had lots of friends who were either Jewish or Christian. Carolos and Ernesto Cohen and Ivet's father Isaac Beja were really good friends especially before Carolos got married.

Ernesto's family seems to have had a lot of money and when his father died he was left with a fortune, a shop and cash. He was a communist and he didn't care about money, so he either spent it or donated it to the Party. He managed to end up with nothing to his name.

Eventually, around 1925 he and his family had to move to Paris. They had a very hard time there as everyone had to work; he, his wife, his brother, his sister and their mother. His sister was married to a very difficult man, Beja. He had been married to a woman called Rinet with whom he had a daughter with red hair, very beautiful, but he got a divorce when in Paris. Being a communist he enrolled in the Red Brigades, to fight Franco in Spain.

All this time that Ernesto was in Paris, my father hadn't heard anything of him. After the war people tried contacting each other, my father went to Paris but didn't find him and then he went to London. It seems they were looking for each other.

The story is that Ernesto was probably captured in Spain and was taken to England. Carolos appears to have found him somewhere in England really tired and old in the company of this English woman, who took care of him, and he had a son as well.

Carolos had a really good friend, who was the director of Emporiki Bank [Commercial Bank of Greece], and he was the one who helped us to leave Thessaloniki safely when we had to. Moreover my father had two or three other really good friends from the time they were all single; only he was Jewish.

All these friends of his helped us to hide and leave Thessaloniki when the deportations began. They wouldn't come to our house as it was not safe back then to have men coming in and out of the house but my father saw them frequently. Almost every day he would go to their offices. Some of the names of these people I still remember: Hatsithomas, Kostandinidis, Petros Pougas and Laskarides.

The thing I remember most about my father is that he always worked long hours, he would spend the day out of the house working and in the evening when he came home his feet would be swollen. He always took a long bath in order to soothe his feet.

Even during winter when it was really cold and snowy he would get up early and go to work. I remember once when it was snowing he left the house and fell over because of slippery ice and had to stay at home for 35 days.

Carolos was active in the Jewish Community; he was serving as a member of the board when the German army arrived. He was responsible for the allocation of housing in the Jewish neighborhoods. If a place in these camps became vacant it was his responsibility to allocate it to others. He was dealing with all of this from the early hours of the day; he always left home at 6am in order to have time for everything.

He was not very religious but he never stopped being Jewish. You could say he was conservative. His mother tongue was Ladino and he spoke good French. He didn't know Greek and he didn't serve in the army.

My mother was called Mathilda and she was born in Thessaloniki in 1898. Her mother tongue was Ladino. She was beautiful, a brunette, and combed her hair in a modern way; she went to the hairdresser's and did lots of different things with it. She always dressed according to the latest fashion.

My mother lived in Paris from 1910 to 1915 where she studied to become a teacher, and then worked for a year in Casablanca, Morocco. After that she never worked as a teacher again. During the war she was in Athens and that is where she stayed after the Liberation and where she died. My mother wasn't very religious either.

My mother's sister, Sarah, was not married and lived with us. Sarah was older than my mother. She still had Spanish citizenship as she had kept it all her life; my mother lost hers when she got married. Sarah had come out of World War I sick with tuberculosis.

She had to go to Davos to a sanatorium to get better. She went there in 1924. She left her mother and went to Switzerland, my father used to send her money and support my grandmother as well. She weighed only 42 kilos when she first got there.

My parents' social life always had to include Sarah and that could be an issue. But as I have already said, families were tight-knit and helped each other. There was also Sterina, the sister of my grandmother Saporta. Carolos used to take care of her and her family too. Sterina's daughters were called Sarah Shoulam and Kouenca; they were my mom's cousins.

I wouldn't describe my parents as religious really but they were conservatives for sure; in our house we kept the traditions.

Their mother tongue was Ladino and they both spoke French as they had both graduated from Alliance. My mother Mathilda really enjoyed speaking French; she read in French and loved reciting French poems.

My parents mostly read history books and literature and my mother used to do recitation. They both read whenever they had some spare time. My father mostly read newspapers but he did read books as well, the time he most often read was when he got up in the morning.

He mainly read 'Le Temps' which eventually became 'Le Monde.' He chose not to read the Jewish papers of Thessaloniki as he spent all his time down in the market and so had no reason to.

They would encourage me to read as well but I was lazy and my mother would pester me about it. Thessaloniki didn't have a library, or at least I don't remember one. My parents were not really the sort of people to sit and read history through specialized books.

The books they read, they bought, and I still have some of them here in my library. I actually don't know if these are books my father had before the war and managed to save or books he bought later. These books with the colored jackets that you can see in my library were his.

We had electricity at my father's house but we only used it for light; it was too expensive to use it for heating. We even had an electric cooker but we never had time to connect it as the Germans invaded.

We never had a cook in the house. It was always my mother who cooked. I never had a lady to look after me. I once tried to learn the violin but it was a disaster.

We didn't have a car in Thessaloniki but my father had a friend who owned one and he would come and pick us up for a ride. It was a Dodge with a convertible top. Men used to go out on their own sometimes back then and they took me along with them.

When my father was a young man, socialist principles and the socialist party in Thessaloniki influenced his views. However when he grew up and started becoming someone of importance, he became a boss himself; when he started earning money he abandoned socialism and was never a member of any political party. What my father really wanted was to become Greek in essence.

Later on though, when things started becoming hard for Jews, he became a member of Keren Kayemet 8 and worked really hard to help all the immigrants who were leaving Europe and were passing through Greece on their way to Palestine; they had nothing to their name and my father was fundraising for them.

He never really thought of leaving Greece himself, I would think because he had a fully functional business in Thessaloniki and to go to Israel seemed hard. He didn't know any Hebrew; that is, he knew enough Hebrew to read the Haggadah but that was it. He even did business with Israel but still he never considered immigrating there.

My father had finished the Alliance School and my mother Mathilda too; she also studied to become a teacher, as I have already mentioned. Her diploma is hanging on my daughter Mathilda's wall.

The story of my parents' meeting is a really interesting one. When my mother graduated from the Alliance School she was sent to France to do her teacher training, while she was there World War I began and she had to stay there. When she finished her training she was sent to Casablanca in Morocco to teach. She stayed there for a couple of years and when the roads were once again open she came back to Thessaloniki.

She arrived at the port of Thessaloniki and the story has it that my father Carolos was thunderstruck. He saw her coming down the stairs of the boat, decided she was the one and they almost eloped. Back then to get married one had to go through a whole procedure; he didn't want to delay so he took her to Venice and it's there the ketubbah was written and they got married. It was exactly the opposite of an arranged marriage! They were married one year before I was born in 1924, and my mother got pregnant soon after they were married.

Mrs. Aglaia Schina owned the school I went to for elementary education. It was right next to my house in Analipsi where we lived when I was young. It was a mixed school with many Christians and many Jewish students but we all studied together.

Among my Jewish classmates were a boy called Allouf, who was a very good student, and a boy called Salmona. The reason I went to a Greek school was because my father realized the Greeks had come to Thessaloniki for good and the one sure way to survive was to know the Greek language well.

I had lots of friends from school and I used to play with them in the neighborhood as we all lived close to each other. I have a friend from that school who still remembers me today; he is a doctor at the Mitera hospital, which is a maternity hospital.

High school is a different story, we didn't have sports teams and EON 9 was active already and so anti-Semitism was obvious by then, and we were not included in any of that.

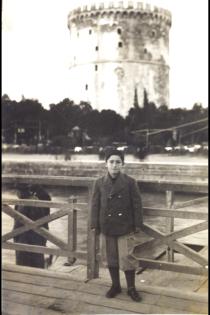

To get to the high school I had to take the tram, it was a vocational high school, as they called them then. It was situated at the YMCA [XAN] building which recently burned down [in 2005], just close to the International Fair complex in Thessaloniki.

In that school the ratio of Jews to Christians was almost one to one. We were all in the same classes. I didn't really have a favorite course and I can't say I was a great student. I have no memory of any special incidents that took place in the school.

Anti-Semitism was sort of legalized at some point though and it became very obvious at school. Every Wednesday they would gather up all the Christian students and have a few hours of 'political education,' which meant that everyone that was member of EON - Jews were not allowed to be members - would be rounded up and indoctrinated with nationalistic and anti-Semitic propaganda.

They didn't have to march, which was what they did with EON, but they were taught lies about the involvement of Jews in the fight to free Thessaloniki from the Turks. We were rounded up separately and did nothing but still we were not allowed to go home. This is how anti-Semitism began in the schools.

The last three years of school in Thessaloniki three brothers appeared at the school; they were called Asseo. They were from Vienna, their mother was Viennese and she was a really good piano player. Their father had died and they came to Thessaloniki to survive.

When the transportations began their mother went to the Germans and said that their names weren't right and that they weren't called Asseo but Gelbart and so they were baptized Gelbarides. George, Alexandros and Carolos Asseo became Gelbarides. We lost contact during the war but I know Alexandros had tuberculosis and he came to Athens where he died shortly after.

George lived for a long time in Thessaloniki and was always very clever and educated. They were all very educated and when they came to the school they made all of us feel useless. George had scoliosis, a serious condition. He got married in Thessaloniki and had a girl.

Carolos, who was really young when they first arrived, went to school after the war and then was hired by the Red Cross and later got a job with BP. He was very successful in BP because he was multilingual and they used him for different positions. He was sent to Italy and the UK and ended up being General Director of BP Italy. He always kept the Gelbart surname.

My father found him after the war; they met up in Spain at a Chamber meeting. Gelbart would always send us a special card to let us know that he was moving houses, it would say, 'Mr. Gelbart will be residing at this and this address from this and this date.'

They were really saved by their mother, who survived during the war by doing translations from German to Greek

As for private lessons at home, I studied French with my mother, who was a teacher. When I grew up a bit I started going to the Lycee Francais to learn it properly. I tried to start learning Hebrew for my bar mitzvah but the Germans invaded and I couldn't carry on.

We were going to Baktche Tchiflic. I never had a pet and we never really cultivated the land ourselves.

For holidays we would go to Florina and then to Pelion, I remember both places being very beautiful. We would always take the train to get to our holiday destination. I remember that most summers before the war, we spent our holidays in Florina; back then the sea wasn't as popular for vacation as the mountains.

I think that was because many people had weak lungs. My parents never went on holiday without me. I had never traveled abroad before the war. I remember playing in Florina with some Greek boys; one of them was called Varadinis, and later became a doctor, and some Jewish kids called Avagiou.

I remember that once we went walking and saw this school with lots of girls. It seems it was a House Economics School for Girls. The Greek state was trying to harness the Greek spirit in the areas around the Bulgarian border. The girls were being taught Greek above all.

So in 1933 there was a 3E phalanx 10. The 3E were nationalists, who used to wear yellow armbands and had the two-headed eagle and flags. They would stroll around Florina and do whatever was possible to Hellenise Macedonia. You see back then in Florina they spoke the Vlacho-Serbian dialect and not Arvanitica. We were in Florina and suddenly these people showed up and started marching.

- During the war

We were in Pelion when the war was declared and I remember the panic among the tourists there. Loads of Greeks from Egypt were on vacation there and suddenly they all found themselves in the middle of the war zone and so they all hurried to the ports to get boats back to Egypt.

All my cousins were older than me and went to the Italian school and I had one more cousin in Athens, the son of my uncle Morris. My other cousins were called Tazartes and were the sons of Loukia. They all were very good students. When I grew up a bit I had one cousin I used to hang out with even though he was older, I used to go the cinema with him.

His name was David Benveniste. We would go to the various cinemas in Thessaloniki, as there were lots of them around town. As he was three or four years older than me, he took on the role of my guardian.

We used to play various games in the street with other kids, like the one called 'tsilika tsoumaka.' I guess I should explain what that game is as people these days don't play it. You have four pieces of wood, three of them long and one short.

So what you do is make a small hole and you put the small piece in it and hit it with the long one to throw it far away. We also used to chase each other and played all the typical games everyone played in the street. We were totally integrated into the Greek environment.

The children I used to play with in the neighborhood were not only Jewish kids but Christian as well. I never had the chance to be in a sports team as the war began, and I was just about to turn 14.

We always had good relations with our neighbors, Jews or Christians, apart from one incident when someone started throwing stones at our house but that was only once. The rest of my family lived around Thessaloniki and even though we never had a standard day we met up, we did see quite a lot of them. Big families always have their fallouts but in general we all got on.

On Saturdays we went to school and I never went to the synagogue apart from when I was really young and my grandmother Ester would take me to the synagogue to light a candle. Generally, as I grew older I would go out on Saturday night, to a movie with my cousin, as I have mentioned above. I never went to the summer camp because there was only the YMCA [XAN] summer camp and they wouldn't have us.

For summer my father and a friend of his, Anton Cohen, would rent a boat and go from the house to the market in it. They did it for exercise I think. A fisherman would wait for them; they would row to the market. I would go with them and when they went to work I would walk around town and then take the tram back home.

We generally kept Jewish traditions at home. We would keep the taanit for Yom Kippur and we would have a seder table for Pesach. We didn't really keep the Sabbath though.

What I remember vividly is that when Pesach was over, and spring had already begun my grandmother Saporta would take me out to the fields and we would collect some grass and bring it home to throw it around the house and she would say some words. It was like a ritual to bless the house, I think, but I have no idea what she said.

My grandparents didn't go to the synagogue for Sabbath, rather my grandmother would light a candle every Friday night. The truth is that my grandmother Saporta did keep the Sabbath and up until we came to Athens the women in the house wouldn't cook on Saturday.

In Thessaloniki there were two or three factories that produced matzah, it wasn't like today when we buy it in boxes, you had to get big pieces of it and there were the 'hamalides' [hamal in Turkish means porter] who would carry them home.

Moreover I remember that all cutlery and plates had to be changed and so we would bring out the 'losa,' which is the box with the special utensils for Pesach. They would take everything out of the box and wash it and that's what we would use over that period. The box was sent to the matzah factory, which we use to call 'la fabrica de matza' and it would be filled up with matzot and sent back home with the 'hamalides,' and we would eat from it throughout the whole Pesach period.

The women of the house would cook all sorts of traditional Pesach dishes; I remember particularly a fish they used to make with vinegar. It was my grandmother's specialty: 'peshe en salsa.'

Even if they cooked ordinary food it would certainly be kosher. The seder would take place at our house and it would be attended only by the close family that lived together. At the head of the table my father would be seated and on his right my mother and next to her Sarah. I don't ever remember having someone outside the family at the table. It wasn't at all like today when we have huge tables with all the extended family.

I don't remember Rosh Hashanah, they probably did what we do today: 'rodantsas con calavasa' and 'rodantsas con spinaca.' However, I do remember Yom Kippur and I remember Saturdays: my mother wouldn't cook on Saturday, she only started cooking when we moved to Athens. For Pesach my father did the whole seder dinner in Ladino; we had a recording of him but unfortunately the tape disappeared. It was impressive as it was all done in Ladino.

For Yom Kippur they would keep the taanit [fast], even my mother and grandmother did so. My father would take me on Yom Kippur to a really small synagogue in the Allatini orphanage for boys and we would spend the whole day there. He would normally keep the taanit but sometimes he didn't, as he was liberal when it came to traditions.

Some of the institutions of the community in Thessaloniki I do remember. There was the renowned Bikur Holim [Hebrew for 'visiting the sick'] for children and people with no income. Furthermore I remember several Jewish Cultural Clubs that had their receptions at big venues.

The most famous one was the hotel Mediterranee, which was later demolished in a night as it was in a really bad state. It was situated on the beach and it used to be very elegant and grand; the community of Thessaloniki would use it for the big celebrations.

Before the war there were touring orchestras that traveled from town to town, one of them was Attic, an old singer and songwriter; very famous before the war. And another band from Argentina with Eduardo Bianco came to play every year.

Two three years before the war was the last time he came. He sang in Spanish and as the majority of people in the community were Spanish speakers, the band was extremely popular; they would come for a month and stay for five. I used to go and listen to them with my father even though I was still young.

The first time I actually experienced anti-Semitism was this one time in the area of Analipsi on Petros Sindika Street and Trapezoundos Street. Pipiliangopouli was the name of the neighboring family at that house. They were a bit anti-Semitic, once their children threw rocks at our windows. That was around 1938-1939; the atmosphere had begun to change and become hostile.

Another time the 3E were going to Thessaloniki for a big meeting of EON. They had brought their children and there were people from all around. A horrible accident occurred. On the trains in Thessaloniki there were too many people and because it was summer and really hot, the children rode on top of the train instead of in it; but there were bridges on the rails and for anti-earthquake measures the tunnels had some metallic beams running through on top of the wagons.

So as a wagon went into the tunnel there wasn't much space on top of it. As the wagon went in on that occasion the children who were on top were crushed and killed. This was sometime between 1934 and 1940. It was big news in Thessaloniki back then. Lots of kids were killed.

I remember that in our house we always had a radio as I had an uncle who imported radios. That was my father's brother Elias who at some point had worked with my father just like most people in the family. So basically we always had contact or information about what was going on in the world. My aunt Sarah would listen to it all day and she would tell us the news.

One day I remember my mother walking into the room at 6am and saying, 'So guys do not get scared, but the war has been declared.' And that was it, that was the beginning of the war for me. Everyone was out on their balconies.

We actually didn't stop going to school as the authorities were afraid of the Bulgarians and so wanted to keep the Greek spirit going. We went to school until the Italians started the air strikes over Thessaloniki 11 and we were all sent home.

At the house our neighbors and my father had decided to build a concrete bunker in the basement with a separate entrance and exit. So whenever we heard the sirens we would all go to this bunker. In the meantime, everyone from the neighborhood went to a newly built French school that was close by in order to hide.

However, to get out of the house and go there it was really dangerous so what people did was to have the back doors of their houses open for anyone to use instead of walking through the streets. These doors connected the houses and so when the sirens sounded people would use them to go to hiding places. It was this way that people kept moving around town even after the Germans imposed a curfew, from one house to the next and so on.

I am sure you have heard of the call for all Jewish men to go to Eleutherias Square 12 when the Germans entered Thessaloniki. At Eleutherias Square neither my father nor I went, as he was a year older and I was a year younger to the age limits.

In order for anyone to travel through Greece, they had to have specific documents and permits. In effect we were stuck in Thessaloniki. Jews were not given permission to travel; however my uncle Elias and a friend of his left in a boat from Thessaloniki to Katerini and from there they moved south.

Jews were all denied permissions, and I remember the Governor General of Macedonia, his name was Kirinis, had a lot to do with it. He knew it was impossible to travel safely without the right papers and still he would deny all Jews permits. When the Germans arrived it was possible to move around the country, as there was no police or a functional state mechanism really.

My father used to travel a lot at the time, as there was big movement in the area of his profession, foreign exchange and golden liras were very popular. He would travel by taxi. There were both buses and taxis working on gas instead of petrol which was produced through an incomplete burn of charcoal. If you burn charcoal at the point were it starts going reddish it produces carbon monoxide, which is a source of energy able to mobilize engines.

My father, apart from the work he had to attend to in Athens, would always take two suitcases full of food for his brothers there because at the time there was almost a famine in Athens. My father was such a courageous man; he had certain strength, which is impressive. The reason he actually went to Athens was that if he bought golden liras for 200,000 in Thessaloniki he could sell them for 400,000 in Athens. He was a really strong man, my father.

When the Germans ordered the Jews of Thessaloniki to present themselves in Eleutherias I didn't have to go, as I was a year younger and my father was a year older than the ages required.

I have already mentioned my father's involvement in the Jewish Community. When the Germans took over Thessaloniki, they rounded up all the Community Council members and put them in a house and interrogated them, in order to learn the things they wanted. I have no idea what that was though.

They kept them there for about 15 to 20 days and then let them go. They used an interpreter, a guy who lived in our neighborhood. His name was Faidon Kontopoulos. While they were being interrogated by the Germans, he had the courage to tell my father and the others, 'Do not listen to them; do what you have to do if you want you answer, if not don't.' He helped them a lot at the time, which made my father respect him greatly.

He left for the Middle East and when he came back he was studying Chemistry in the Polytechnic School at the same time as I was studying to be a civil engineer. He was a few years older than me and he was tall and blonde. My father was very fond of him; he was a courageous man, a good man. Eventually he married a Jewish girl of the Saltiel family.

We left Thessaloniki just after the first deportation took place. Let's take it from the beginning though. We originally moved to the ghetto close to the train station. We took only our clothes and left everything else. Some of our stuff we gave to an Armenian friend of my father who had a warehouse to store them in.

When Thessaloniki was being bombarded most things got burned but the carpets were still in that warehouse. In these carpets my parents hid pictures and documents, which I still have. David Benveniste was my cousin and the Germans eventually took him. We found out while we were still in Thessaloniki.

You see, the whole of Thessaloniki was split in different ghettos 13 and deportations were taking place ghetto by ghetto. So people from the ghetto where they were staying were deported before we left Thessaloniki.

At the beginning we were in a ghetto in the market so my father could still be in contact with the city centre and the market. My father wouldn't give up; he would go to the market every day as the ghetto was just there. When the first train was filled and left the station, I was there as a civil guard with one of my cousins, and then we moved to another ghetto.

We were given the duties of civil guards by the community in order to help out in little side jobs and we wanted to be part of that so we could move more freely in the ghetto. The worst part was that we had to help people get into the trains, mainly the elderly and children.

It is there that I saw through a window that Ericka Kounio was being deported. I didn't see anyone else I knew, probably on that same train there was my mother's cousin but I didn't see her. The lines of people were moving women, children, old people who couldn't climb on the wagons alone and our role was to help them.

When this whole issue of the deportation finished and we went back to our family, we recounted everything we had seen and it was at that moment that the decision was taken, we would either be caught or we would get out of there.

The day before the first transportation from our ghetto took place we moved ghettos and went to the other one. I don't really remember the second time we moved, as we really didn't have any stuff any longer, we had left it in our house on our first move to the ghetto.

My father was really a blessed man, charismatic. He had a friend in town; in order to go and see him he went into a park and took off his coat and turned it inside out and carried on in town. As my father was a member of the community council he had to wear a yellow armband when he was out, that is why he had to turn his coat inside out.

He went to meet his friend Giannis Hatzithomas, who was a very good friend of his and the director of the Commercial Bank of Greece, and he said to him, 'Giannis, I don't know what you are going to do but I have to leave, I don't care how.'

This Giannis, a hero himself, had some cousins who worked on the railways, and with money and lots of courage they agreed to help. It was me that left first with a friend of my father's named Sam Saltiel. Just before we set off my father said to him, 'Sam, toma el chiquitico [take with you the child] and whatever luck you have...'

So at night we wore a blue coat and a railway hat each and we got into the train station that was guarded by the Germans. While the Germans were inspecting the train carriages we would jump from one wagon to the next to avoid them.

Finally we were put on one of these wagons that have a platform and a small house-like building on it. Back then the trains didn't have brakes that worked with air like today but had mechanical brakes that had to be worked by someone. That's why there were these people working on the trains.

Our goal was to get past Platamonas because the Germans and the Italians had split Greece into two. Platamonas is a bit further north than Larissa. When the train got to Platamonas we had to hide in these house-like buildings each in a different one and we got past the checks. It felt like we had been saved because the Italians were much friendlier towards the Jews.

We carried on to Larissa where we found some other Jews we knew and they helped us go to Volos where some other Jews helped us out. We got on a truck that carried cotton wool and made it to Athens. It took us two days to get to Athens where we met my uncles and they had already rented a house for us.

When the news of our safe arrival reached my father through a telephone call from one of my uncles, he took my mother and they made their way down to Athens as well. They had to act as we did, hide to get past Platamonas and from there to Larissa. There the Fais family - may God keep them safe, although they have passed away and only one of the daughters survives - helped them out. Imagine that one of them even offered to escort my parents on the way to Athens. He did so because my father didn't speak good Greek. He brought them down to Athens and made his way back to Larissa.

My grandmother Saporta had already died in 1931 when there was a typhus epidemic; today typhus barely exists. Sarah had Spanish nationality and so didn't come down to Athens with my parents. She was waiting to leave Thessaloniki with the rest of the Spanish nationals but she couldn't be separated from the family and so eventually got in touch with the people who helped us get down to Athens and she suddenly appeared in front of us there. So eventually the whole family was reunited.

We stayed in that house on Solonos Street for a while, up until the Italians had to surrender, Badoglio 14 did. When the Italians lost power, things became totally different and the German Occupation started [in September 1943]. Then we decided once again that something had to be done. Our house was on Solonos and Lecabetus Streets; it's since then that I started claiming I am an Athenian.

When we moved to Athens I decided I would try to get into the Polytechnic School to study Civil Engineering so I was preparing for the exams and was enrolled in the Polytechneion to take them when suddenly something happened, I don't exactly know what.

The government had several young soldiers who were studying at the Military School for Career Officers - Evelpidon - who were sent to the Polytechneion in order to either train or at least stay out of trouble. So one day we were taking the exams when during one of the breaks some kind of upheaval was obvious. No one had realized what and why there was much movement but suddenly someone called out loudly, 'The Germans the Germans...'

The Polytechneion has walls all around it, so we were trapped. I was looking around me, I had no papers or the ones I had were faked so I could not be searched. I was looking around and suddenly I saw on one side of the wall towards Tositsa Street there was an old cooker left there, and I saw these little kids climbing on the cooker and over the fence and out on the street.

I decided I was going to do the same thing and climbed on the cooker and on the wall, and it was only then I realized that it was four to five meters high. I had no option, so I said to myself, 'you either break a leg or you get to survive,' and jumped.

I got up and crossed over to the other side of the street where the museum is and walked casually along. I walked 200 meters and the first German appeared on the side of the Polytechnic holding his machine gun so others wouldn't jump over the wall. That was the end of my exams; I took them again after the war.

It was then that another of my father's friends appeared. In one's life, if one is a good person, well respected and loved by his/her friends, the most important thing one possesses is friendships!

So this man arrived, a friend my father had helped back in Thessaloniki through a tough period in his own life. You see, my father was very generous and everyone that knew him well enough called him Charles. This friend then goes, 'Charles, I still haven't thought of what you and your son are going to do but your wife and sister-in-law I will take with me to my sister's house, in Kalithea.'

My mother Mathilda and her sister Sarah stayed in Athens, and my father and I were sent to Leivadia where there was a plain, the Copaida plain. It was through the Resistance that we were sent up there. Around the Copaida plain there are some villages.

We were sent to a doctor up in a village and he sent us to another village, where we stayed. It was difficult to live up there in a small village. That was all happening in 1943 after the Italians had capitulated.

The village was called Pavlo and there we rented a small house and stayed there trying to survive just like everybody else did. Before leaving Athens my father gave the friend that was going to hide my mother and aunt all his money and asked him to send us some money when he could.

Money back then was gold sovereigns [liras]. Athens in those days was supplied by the black market merchants that would go around the villages and would barter, for example, twelve eggs for some flour and so on.

One of these merchants was in touch with our friend in Kalithea and my father had a code with him that he would send a note, which would say how many liras we needed. This black market merchant would bring the money each time. May God keep him safe! It was with these liras that we survived even though we really lived on bread and onions, as there was not much else in the village.

My father's friend Sam Saltiel, with whom I came down from Thessaloniki, didn't come up the mountains with us, but was saved as well. There were these two brothers though that came along with us, the Cohen brothers, who were old friends of my father. Together with them we went through the occupation and then took our separate ways. We would hear news of the well- being of my mother and aunt through the same black market merchant; this man never asked for anything in return!

The rest of the family hid as well, my uncle Elias found a girlfriend who agreed to hide him and his brother and their mother. My uncle Morris hid with his wife and child somewhere else. I have to mention that all of them survived on the money that my father had stashed away.

My cousin, the daughter of Alegra Brudo, my father's sister, who now lives in the USA, still remembers going to Mr. Depasta to be given one golden lira. Everyone did the same; thank God there was this money!

While we were hiding in the mountains we never experienced any anti-Semitic incidents. When he was young, my father was a member of the Zionist Federation, which was a bit left-leaning. So he knew a few things to help get around, he knew Communist songs in French and he used to sit in the Cafenio [café] of the village with everyone else and he would lecture them on Communist theory and teach them to sing these songs.

It was in that village that I first heard that the British were planning to land. In that village they had a coal mine, essentially big holes in the mountain that they would produce iron from. It was there I hid my radio and a car battery; we would go each day and listen to the news. The news would be broadcast in English on the BBC World Service and, as I was the only one to know English, I would listen and then report to the rest of the village.

One day I went to listen to the news and I couldn't understand anything. I remember the BBC signal very vividly: 'dan dan dan....dan.' I tried to understand but couldn't make out what they were saying. It seemed some irrelevant stuff but slowly I realized they were talking about thousands of airplanes and thousands of boats.

The World Service was reporting the D- day, the day American and British troops were landing in Europe. It took us a while to realize but once I did, I told the whole village and the nearby villages as we had a loudhailer to inform the villages further down.

There was widespread enthusiasm. It was the beginning of the end; it was 10th June. By September the Germans had been defeated and the war finished for us when the first English parachutist was dropped over Leivadia and jeeps full of British soldiers came to Leivadia. That was the end of the war for us. Everyone was very excited.

We left the village the next day. My mother and Sarah hadn't had any problems, the people they lived with, the sister of Mr. Depasta and his nieces, were really good people and took care of them. They had fake papers and all.

We left the village and came down to Athens, to our little home on Solonos and Lecabettus Street; we had nothing but beds. The Joint Distribution Committee 15 was already active in Athens and was helping Jews resettle, giving out rice and all sorts of supplies which one could go and collect. The Jewish Community of Athens was just starting to recover with the help of the Joint Distribution Committee. It's a different story what happened from then on.

When the partisans came down from the mountains to take over Athens the fighting began. The Communists had a machine gun at the end of Solonos Street and one couldn't even cross from one side of the street to the other.

The area from around our house to where the Ministry of Foreign Affairs stands [currently at Zalokosta Street] was 'free'- meaning not controlled by the partisans but by the British. There was intense fighting going on in Athens at the time. There was a tank that every evening would go up Deinokratous Street and get to Lecabetus and from there it would fire down on Exarheia.

The shooting was literally next to us. I have very vivid recollections of sitting in our kitchen, trying to stay focused on what I wanted to achieve, which was to enter the Civil Engineering school in Polytechneion. I really wanted to study and do something with my life, but trying to study after we had finished dinner and hearing the fighting so close... I can't even describe it to you.

My father started working as soon as he could; he took off for Thessaloniki to sort some inheritance issues of my mother's and when he realized it wasn't worth it he left and came back to Athens to start work. Our house in Thessaloniki was completely looted apart from the famous mirror.

After the war we found our stuff, or what was left of it, and my mother kept all of it at her house. It was only after she died that we found everything, even a dress she wore in Venice, where she got married, and you can see it in a picture I have. In this picture you can see them both dressed up in the clothes people used to wear back then in 1925. You can also see the pigeons in the square!

The other item we rescued was a mirror; it still exists in my daughter's office. That mirror was in our house in Thessaloniki. My father had bought it from the Turks at the time of the exchange of populations [cf. Treaty of Lausanne] 16, when the Turks were selling everything on their way back to Turkey.

He bought the mirror and two carpets. We had this mirror in our living room, and, when the war was over and we found it in the house, my father decided to bring it to Athens and put it in the house we moved to on Academias Street. It was always the jewel of our home.

When he died we thought that we could get rid of some furniture we didn't need and realized that this mirror was so tall; made for houses with a higher ceiling than the ones built today, so we couldn't even move it from the house. The mirror is around 3 meters tall and the houses today are around 2.7-2.8 meters high. I believe the mirror only survived the war because of its immense size and weight; nobody could move it so they left it where it was.

- Post-war

Slowly the whole family was reunited. My father's brothers and my grandmother had a house up in Kolonaki close to Dexameni; it is still there, it hasn't been demolished. Morris showed up and Mimis the cousin as well and life took its normal course.

People started immigrating to Israel and the USA, even members of our family decided to leave, my father's sister Alegra Brudo and her daughter, who was studying to be a dentist, and her husband left for the USA. The daughter finished her studies and joined her husband and mother in the USA. I still have contact with her.

There were many people leaving at the time but I don't remember names. The truth is I never thought of leaving, as I never really struggled for survival.

We stayed in the house in Solonos for a few years; we didn't have any money left. I got admitted to university and had to study at that same kitchen table after dinner; imagine that. But it was all right, as I had to go to the army after two years since I was a student, everyone else had to go for three years. After that I had to go back to that small room; by then I was grown up.

My father was wandering the streets looking for a more spacious apartment or house for us to move in to. It was Sunday morning, really early, and my father got up and went for a walk in Kolonaki, in order to check if anything was being rented out.

As he was strolling along he saw this guy he knew from the old times - another broker. And he said to him, 'What is it that you are doing wandering the streets at this time of day, Charles?' And my father replied, 'I am in trouble, I have my son coming back from the army and I can't find a house.'

Upon which the other guy replied, 'Is that all you need, a house? So, how about this one here, it's mine, do you like it? You can have it it's empty.' And my father said, 'Well, that's great but I have no money.' And the old friend replied, 'So what, you take it and when you have money you give it to me.'

That is how we got the house on Academias Street, where my daughter Matilda has her office now. I really don't know if people realize how important it is to find someone who tells you, you can have a house and not worry about money. Once again, friends are proven to be the most valuable asset one has. If you are not brought up properly and don't have good surroundings, then it's really hard to become someone, or that's what I think anyway.

I was at university for five years, two before the army and three after it. During that time I wasn't really active in politics. At university I didn't have time for politics, I just wanted to finish my studies. During my army service I was with a distant relative from the Saltiel side, from my maternal grandmother's side. He was from Kavala.

Back then the Americans would accept everyone who came with Joint and would take care of him. So he went and we had a few letters and then he didn't appear again. In addition, during my service, I served with a few people from the Polytechnic; to name but two of them: Stavros Bulos and Nikos. I still see them every 15 days or so.

When I graduated from the Polytechnic University and finished the army I went to Paris where we had some relatives, the Cohens, from my father's side. They were great people; they originally came from Trikala. They left for Paris after the war; they had gone to the Middle East during the war. One of them was a very good lawyer, while in the Middle East he was a corporal for the air force.

So I went to Paris around 1950 to 1952 to do a training program, working for not too much money at an office, as a mechanic for a company. I stayed there for two years and I really enjoyed myself. I felt comfortable, as I was fluent in French. My work included designs and reports, whatever the job of a mechanic generally includes.

I came back because I was the only child and my mother was unhappy about me being abroad but I went on a beautiful trip. I traveled along the French coast to the Atlantic up until Stockholm. I went through France, Belgium, Germany and Denmark and then Sweden. I went alone; I had a car that I had bought with my savings and a little help from my parents. I even had it in Paris for some time.

The whole of that period in Paris was great for me. Imagine, I was just a boy from Thessaloniki, or Athens, and suddenly I was under the Eiffel Tower surrounded by great museums and theaters. I couldn't stand still, I went everywhere. French people are something else. Anyway, after my trip to Stockholm I felt like going back home.

When I got back to Greece I went into business with someone and opened my own office in the center of Athens.

My wife is called Deniz and I met her in the youth club the community ran. Back then we were all one big family. I got married in 1958 and had met my wife a year before...the in-between stage didn't last too long. We got married in Athens at the Beth Shalom synagogue.

The rabbi was called Bartzilai and the funniest part of the wedding was: when he asked me for the wedding rings and I started going through my pockets I couldn't find them. Imagine this: I was in the middle, my father on one side and my father-in-law on the other, and the rabbi looking at me, and I had left the wedding rings at home.

However, my father, quick as ever, took his ring off and gave it to me, and my father-in-law did the same. The rabbi said to bring him the proper ones the day after in order to have them blessed.

The wedding dress was bought and made by a famous designer.

We didn't have a big reception after the wedding; we only had a dinner for the close family and then we left for our honeymoon. We took a car and drove around Europe for a month; we got to Brussels and went to the international expo at the Atomioum. The Atomioum was built particularly for that exhibition and set up in the square. It is a structure that looks like an Atom, very impressive indeed.

We were in Geneva and left the car there and took the plane to Belgium; it was pretty exhausting. We stayed in Brussels for a couple of days and then got back to Geneva and took the car and started our journey back to Greece. The car was a Ford Anglia 1100cc.

My wife's family name is Pardo, and she was born in 1939 in Thessaloniki. Her mother tongue is Greek and she speaks English and French and Ladino. Right after we got married we stayed in the house on Academias Street with my family. It was a big house that could fit all of us, and then we moved to Kolonaki, on Speusipou Street. Very close to both families, as my family lived on Academias Street, and my wife's family on Skoufa Street.

Speusipou is where all our girls were born: we have three children, three daughters. I remember when Matilda was born, I wasn't allowed in while in my wife was in labor but I remember that when we brought my daughter home she would take a deep breath and we would be awake.

The girls all went to the Jewish elementary school, it used to be exactly where it still is, in Psychico. Afterwards, the girls went to the American College of Greece, Pierce College.

After school they all decided to go abroad, the two older ones went to Israel and the youngest one, Sarah, went to Paris. Matilda went to Haifa and Nineta went to Jerusalem; my wife was with me in Jerusalem to get Nineta settled. Nineta also lived in England, while doing a graduate degree at the University of Leicester.

Matilda did her master's in New York, at Columbia University, and then lived there for some time, working. Sarah went to Paris; she was always very talented in dance and so she enrolled at the Sorbonne. She still lives in Paris and has been to the USA for studies, for about five or six years, she would go to the USA during summer and take classes.

I remember when they left for Israel to study, when I had to leave my older daughter in Haifa for her to go to Maon [halls of residence for students attending university in Israel], the student halls, which weren't in the best condition, I thought: 'May God help her.' There were two students in each room and I kept on wondering how she would be studying architecture in that environment.

I remember saying goodbye; it was hard. She studied Architecture and has now her own office and is doing very well for herself. My second daughter studied History of Art and Museumology; saying goodbye to her was easier, as I had done it before. I remember vividly Matilda's graduation from Columbia.

Deniz, my wife was hiding with her family in Thessaloniki during the war and has lived in Athens ever since. She finished high school and she worked with her father for a while. I was never on the extreme in my political beliefs. I have always read the newspaper 'Ta Nea,' and whenever I have some free time I like to read. I read political science and anything else that falls in my lap.

We would go for holidays close to Athens when the children were young; we would go to Glyfada. We would travel abroad either for work reasons or because of some exhibition, but we usually traveled without the children. I didn't really keep close contact with my family, that is, my cousins and aunts and uncles; we would see a lot of Deniz's family though.

We always had friends and most of them have been Jewish even though I had, and still have, good friends who are not Jewish, mostly people I worked with. I never felt discriminated with regards to my religion in my work environment. With our Jewish friends we always spoke about Israel and Judaism but with Christian friends these topics were not really mentioned. I worked for 40 years; I had partners so I didn't work alone.

Two of my daughters are married and have children. I don't have anything to say about their ways of raising their children, each parent decides on his own how to raise his children. They both studied in Israel and are well prepared to teach their children about Judaism, some do more, some less.

I have four grandchildren. Their names are Alberto and Carolos, Mathilda's sons, and Alberto and Mathilda, Nineta's children. They live very close to us and that's very pleasant. My youngest daughter, Sarita, is still in Paris, where she is working.

- Glossary:

1 Ladino: Also known as Judeo-Spanish, it is the spoken and written Hispanic language of Jews of Spanish and Portuguese origin. Ladino did not become a specifically Jewish language until after the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492 (and Portugal in 1495) - it was merely the language of their province. It is also known as Judezmo, Dzhudezmo, or Spaniolit. When the Jews were expelled from Spain and Portugal they were cut off from the further development of the language, but they continued to speak it in the communities and countries to which they emigrated.

Ladino therefore reflects the grammar and vocabulary of 15th-century Spanish. In Amsterdam, England and Italy, those Jews who continued to speak 'Ladino' were in constant contact with Spain and therefore they basically continued to speak the Castilian Spanish of the time. Ladino was nowhere near as diverse as the various forms of Yiddish, but there were still two different dialects, which corresponded to the different origins of the speakers:

'Oriental' Ladino was spoken in Turkey and Rhodes and reflected Castilian Spanish, whereas 'Western' Ladino was spoken in Greece, Macedonia, Bosnia, Serbia and Romania, and preserved the characteristics of northern Spanish and Portuguese. The vocabulary of Ladino includes hundreds of archaic Spanish words, and also includes many words from different languages: mainly from Hebrew, Arabic, Turkish, Greek, French, and to a lesser extent from Italian.

In the Ladino spoken in Israel, several words have been borrowed from Yiddish. For most of its lifetime, Ladino was written in the Hebrew alphabet, in Rashi script, or in Solitreo. It was only in the late 19th century that Ladino was ever written using the Latin alphabet.

At various times Ladino has been spoken in North Africa, Egypt, Greece, Turkey, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Romania, France, Israel, and, to a lesser extent, in the United States and Latin America.

2 Atatürk, Mustafa Kemal (1881-1938): Great Turkish statesman, the founder of modern Turkey. Mustafa Kemal was born in Salonica; he adapted the name Atatürk (Father of the Turks) when he introduced surnames in Turkey. He joined the liberal Young Turk movement, aiming at turning the Ottoman Empire into a modern Turkish nation state and also participated in the Young Turk Revolt (1908). He fought in the Second Balkan War (1913) and World War I.

After the Ottoman capitulation to the Entente, Mustafa Kemal Pasha organized the Turkish Nationalist Party (1919) and set up a new government in Ankara to rival Sultan Mohammed VI, who had been forced to sign the treaty of Sevres (1920), according to which Turkey would loose the Arab and Kurdish provinces, Armenia, and the whole of European Turkey with Istanbul and the Aegean littoral to Greece.

He was able to regain much of the lost provinces and expelled the Greeks from Anatolia. He abolished the Sultanate and attained international recognition for the Turkish Republic at the Lausanne Treaty (1923). Under his presidency Turkey became a constitutional state (1924), universal male suffrage was introduced, state and church were divided and he also introduced the Latin script.

3 The Fire of Thessaloniki: In the night of 18th August 1917, an enormous fire, fed by the famous Vardar wind, destroyed the city centre where most of the Jews lived. It was a region of 227 hectares, where 15,000 families lived, 10,000 of them were Jewish families which were deprived of their homes.

The Jews were hit the hardest, since more than two thirds of the property destroyed by the fire was Jewish and only a tenth of that immense fortune was insured. Nearly all the schools, 32 synagogues, 50 oratories, all the cultural centers, libraries, clubs, etc. were annihilated.

Despite of the aid of a sum of 40,000 golden pounds collected from all over the world, the community never recovered from that disaster. The Jewish face of the city that had been there for more than five centuries was wiped out in 36 hours.

25,000, out of 53,000 of the stricken Jews that belonged mostly to the lower and middle class, were forced to live in the working-class districts that were hastily built in a rudimentary fashion. (Source: Rena Molho, 'Jewish Working-Class Neighborhoods established in Salonica Following the 1890 and the 1917 Fires,' in Rena Molho, 'Salonica and Istanbul: Social, Political and Cultural Aspects of Jewish Life,' The Isis Press, Istanbul, 2005, pp.107-126.)

4 '151': After the Fire of 1917, the Jewish Community acquired the large No. 151 hospital, which belonged to the Italian army and was located east of the Thessaloniki. 75 wooden structures and many brick and cement structures were subsequently built to house the fire-stricken Jewish population.

5 Baron Hirsch camp: One of the poorest Jewish working class neighborhoods near the old railway station in Salonica. During the German occupation it was turned into a ghetto, the so-called Baron Hirsch Camp, where the Nazis assembled the Jews before they deported them.

6 Turkish War of Independence (1919-1922): After the Ottoman capitulation to the Entente, Mustafa Kemal Pasha (later Kemal Ataturk) organized the Turkish Nationalist Party (1919) and set up a new government in Ankara to rival Sultan Mohammed VI, who had been forced to sign the treaty of Sevres (August 1920). He was able to regain much of the lost provinces; stopped the advancing Greek troops only 8 km from Ankara and was able to finally expel them from Anatolia (August 1922).

He gained important victories in diplomacy too: he managed to have both the French and the Italian withdrawn from Anatolia by October 1921 and Soviet Russia recognize the country and establish the Russian-Turkish boundary. Signing a British-proposed armistice in Thrace he managed to have the Greeks withdrawn beyond the Meric (Maritsa) River and accepted a continuous Entente presence in the straits and Istanbul.

In November 1922 the Grand National Assembly abolished the Sultanate (retained the Caliphate though) by which act the Ottoman Empire 'de jure' ceased to exist. Sultan Mohammed VI fled to Malta and his cousin, Abdulmejid, was named the Caliph.

Turkey was the only defeated country able to negotiate with the Entente as equal and influence the terms of the peace treaty. At the Lausanne conference (November 1922- July 1923) the Entente recognized the present day borders of Turkey, including the areas acquired through warfare after the signing of the Treaty in Sevres.

7 Alliance Israelite Universelle: An international Jewish organization based in France. It was founded in Paris in 1860 by Adolphe Gremieux, as a response to the Damascus Affair, with the goal to protect human rights of Jews as citizens of the countries where they live.

The organization was created to combine the ideals of self defense and self sufficiency through education and professional development among Jews around the world. In addition, the organization operated a number of Jewish day schools and has done a lot to standardize the Ladino language.

The Alliance schools were organized in network with their Central Committee in Paris. The teaching body was usually the alumni trained in France. The schools emphasized modern sciences and history in their curriculum; nevertheless Hebrew and religion were also taught. The Alliance Israelite Universelle ideology consisted in teaching the local language to Jews so they could be integrated to their country's culture. This was part of the modernization of the Jews.

Most Ottoman Jews, however, did not take up the Turkish language (because it was optional), and as a result a new generation of Ottoman Jews grew up that was more familiar with France and the West than with the surrounding society.

In the Balkans the first school was opened in Greece (Volos) in 1865, then in the Ottoman Empire in Adrianople in 1867, Shumla (Shumen) in 1870 and in Istanbul, Smyrna (Izmir), and Salonica in 1870s. In 1870, Carl Netter of the AIU received a tract of land from the Ottoman Empire as a gift and started an agricultural school, Mikveh Israel, the first modern Jewish agricultural settlement in the Land of Israel.

The modernist Jewish elite and intelligentsia of the late 19th-century Ottoman Empire was known for having graduated from Alliance schools; they were closely attached to the Young Turk circles, and after 1908 three of them (Carasso, Farraggi, and Masliah) were members of the new Ottoman Chamber of Deputies.

8 Keren Kayemet Leisrael (K.K.L.): Jewish National Fund (JNF) founded in 1901 at the Fifth Zionist Congress in Basel. From its inception, the JNF was charged with the task of fundraising in Jewish communities for the purpose of purchasing land in the Land of Israel to create a homeland for the Jewish people.

After 1948 the fund was used to improve and afforest the territories gained. Every Jewish family that wished to help the cause had a JNF money box, called the 'blue box.' They threw in at least one lei each day, while on Sabbath and high holidays they threw in as many lei as candles they lit for that holiday. This is how they partly used to collect the necessary funds. Now these boxes are known worldwide as a symbol of Zionism.

9 EON: National Youth Organization, founded by the Metaxas regime on the model of the Italian youth fascist organizations.

10 3E (Ethniki Enosi Ellados): lit. National Union of Greece, a fascist nationalist organization, founded in 1929 by George Kosmidis. It had about 2000 members, of whom the majority was immigrants. [Source: J. Hondros, 'Occupation and Resistance: the Greek Agony,' New York, 1983]

11 Greek-Albanian War/Greek-Italian War (1940-1941): Greece was drawn into WWII when Italian troops crossed the borders of Albania and violated Greek territory on 28th October 1940.

The Italian attack of Greece seemed obvious, despite the stated disagreement of Hitler and the efforts of Ioannis Metaxas, who was trying to trying to keep the country in a neutral stance. Following a series of warning signs, culminating in the sinking of Battleship 'Elli' on 15th August 1940, by Italian torpedoes, and all of these failing to provoke the Greek government to react, the Italian Ultimatum was delivered on 28th October 1940, and it demanded the free passage of the Italian army through Greek soil, as well as sole control of a series of strategic points of the country.

The rejection of the ultimatum by Metaxas was in line with the public opinion in Greece and led to the immediate declaration of war by Italy against Greece. This war took place mostly in the mountains of Hepeirous. In the Greek-Albanian War approximately 12.500 Greek Jews took part and 513 Greek Jews died fighting. The Greek counter-offensive pushed the Italians deep into Albania and the Greek army maintained the initiative throughout the winter capturing the southern Albanian towns of Corce, Aghioi Saranda, and Girocaster. [Source: Thanos Veremis, Mark Dragoumis, 'Historical Dictionary of Greece' (London 1995)]

12 Eleutherias Square: On 11th July 1942, following the order of the German Authority published by the local press, 6000-10.000 (depending on different estimations) male Jews aged from 18-45 were gathered in Eleutherias Square, in the commercial center of Thessaloniki. The aim was to enlist/mobilize them to forced labor works. Under the hot sun the armed soldiers forced them to remain standing for hours and imposed on them humiliating gymnastic exercises. The Wehrmacht army staff was taking photographs of the scene, while the Greek citizens were watching from their balconies. [Source: Marc Mazower, 'Inside Hitler's Greece' (Yale 1993)]

13 Salonica Ghettos: The two ghettos in Salonica were established by the Germans on Fleming and Syngrou Streets, in the east and the west of the city respectively. These were formerly neighborhoods with a dense, yet not exclusively Jewish population. There was no ghetto in the city before it was occupied by the Germans. (Source: Mark Mazower, Inside Hitler's Greece: The Experience of Occupation, 1941-44, New Haven and London).

14 Surrender of Badoglio: Pietro Badoglio (1871-1956), Italian general and Prime Minister. When Mussolini was deposed in 1943, Badoglio was chosen to head the new non-fascist government. He made peace with the advancing Allies, declared war against Germany, but resigned soon afterwards (Source: «Badoglio, Pietro».